1/x On 15th April 2014, the South Korea Sewol ferry carrying 476 people which included 325 high school students on a school trip, capsized and claimed the lives of over 300 passengers including the vast majority of students. A 🧵

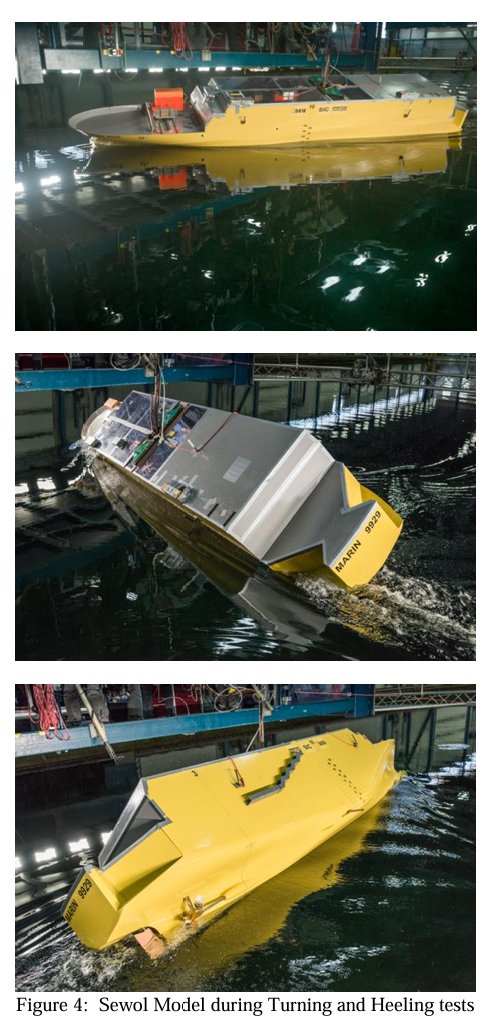

2/x Sewol was a 146m Ro-Pax ferry, originally built in Japan (1994) and later modified in South Korea. Her refit added cabins and cargo capacity but raised her center of gravity dangerously. Stability tests were not properly enforced post-modification.

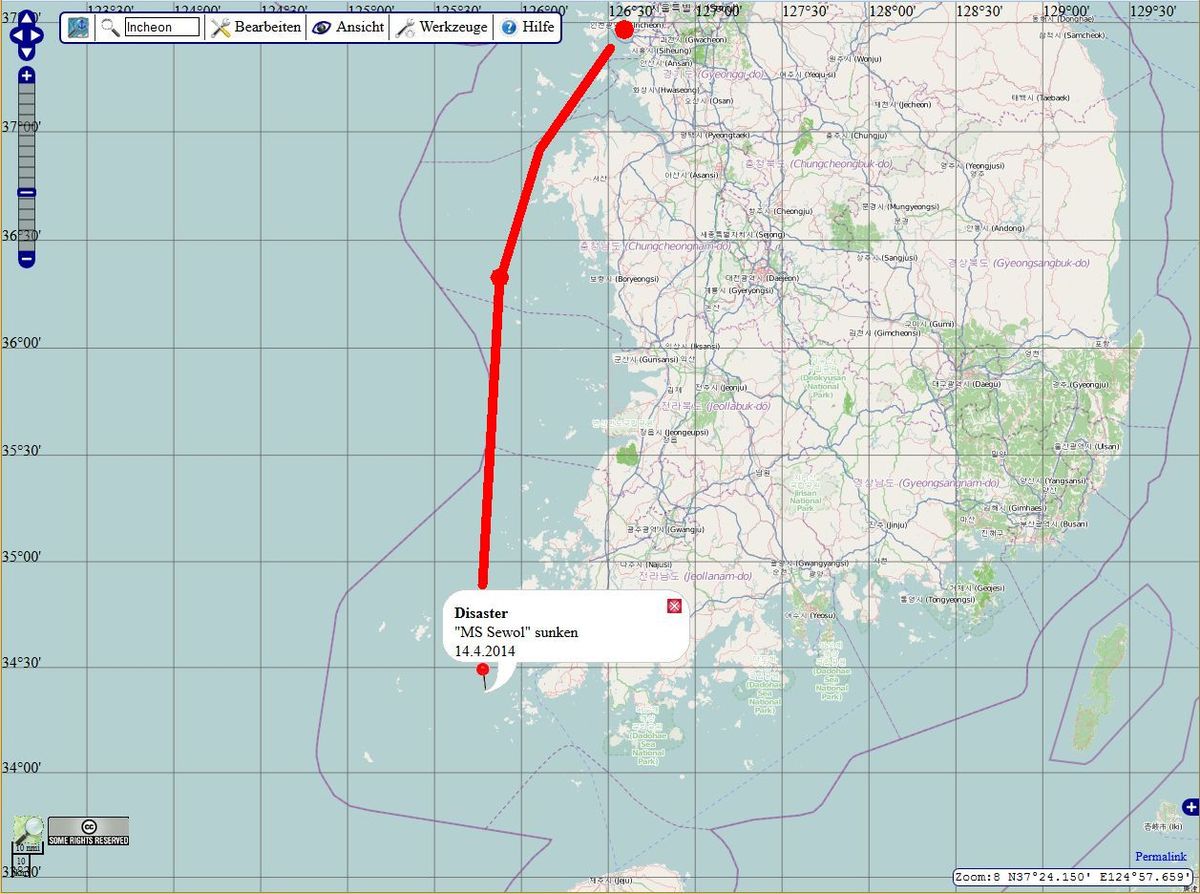

3/x At 9pm on April 15, 2014 MV Sewol, departed from Incheon bound for Cheju Island. The majority of the passengers, 325, were 16- and 17-year-old students of Danwon high school in Ansan City. Despite her maximum allowance for 987 tons of cargo,

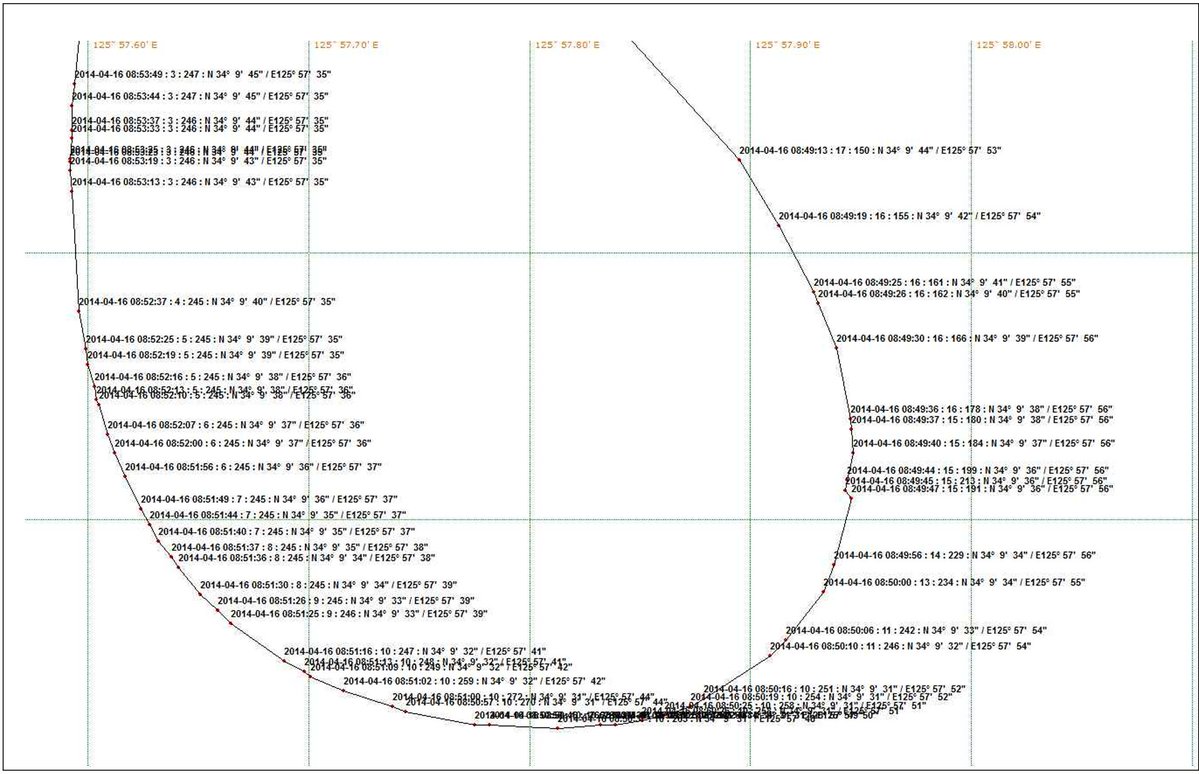

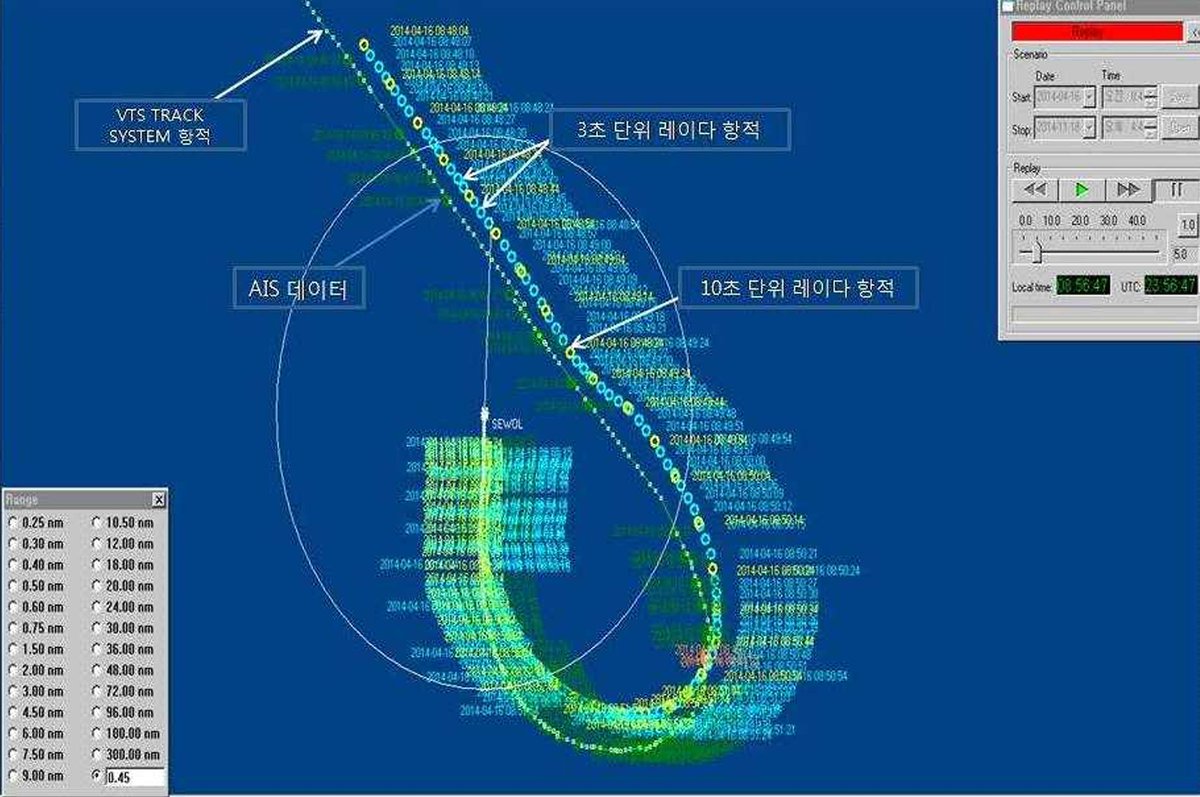

4/x Sewol was carrying 2,142.7 tons of cargo, which had been improperly secured. Sewol maintained a speed of 17–21 knots along its route. At 08:46, the third mate ordered a course change from 135° to 140°. At 08:49, a second course change to 145° was ordered.

5/x The helmsman executed a sharp turn to starboard, causing the ship to tilt rapidly to port. Cargo shifted violently, exacerbating the tilt. By 10:25, Sewol had capsized with a tilt of approximately 108°, and by 10:31, it had sunk, leaving only the bow visible above water.

6/x The captain and first mate tried to use the heeling tanks to stabilize the ship but failed. At 08:55, the first mate contacted Jeju VTS via radio to report the accident and request rescue. The first internal announcement told passengers to stay where they were.

7/x At 09:00, Jeju VTS advised the crew to prepare passengers for possible evacuation and to wear life jackets. However, the second mate instructed the purser to tell passengers to remain inside. The crew contacted the shipping company but did not receive clear instructions.

8/x At 09:13, a nearby cargo ship (Doola Ace) offered to help rescue passengers, but the Sewol crew did not initiate evacuation. At 09:25, the VTS told the captain to evacuate passengers, but no action was taken.

9/x Crew members tried to contact the captain for evacuation instructions but received no response. By 09:39, engine room crew had evacuated to a Coast Guard vessel. At 09:48, the captain and seven deck crew abandoned ship via the bridge wing.

10/x At 09:50, the final announcement told passengers to stay inside. The crew then evacuated. By 09:34, the ship had tilted 52°, and by 10:10, it reached 77.9°. At 10:25, the ship tilted 108° and capsized. By 10:31, only the bow remained above water.

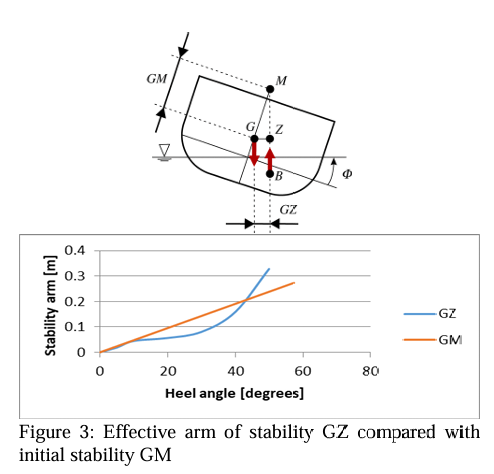

11/x After being modified in South Korea, Sewol’s center of gravity rose by 51 cm, reducing its stability. The ship’s maximum approved cargo load dropped from 2,437 tons to 987 tons, and required ballast water increased from 307 tons to 1,703 tons.

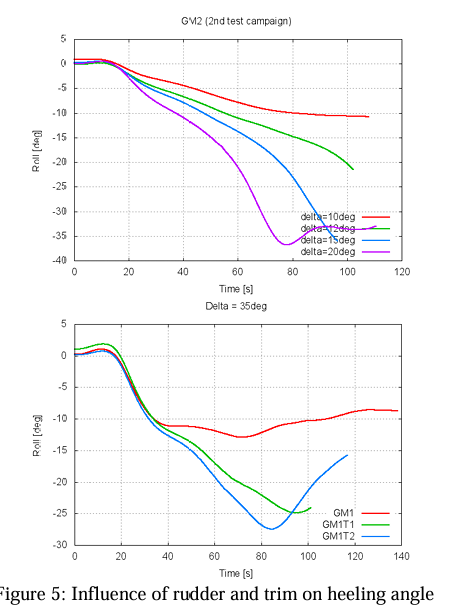

12/x On April 15, 2014, Sewol departed with only 761 tons of ballast water and 2,143 tons of cargo, violating safety standards. The helmsman used excessive rudder angle during a course change, causing a rapid starboard turn.

13/x This led to a sharp portside heel of 15–20°, which exceeded the ship’s ability to recover. Simulations confirmed that such rudder input at Sewol’s speed (19 knots) could cause dangerous heel angles.

14/x Vehicles and containers were not secured according to approved plans. Many tie-downs were missing or insufficient. Containers were fastened with ropes instead of twist locks or bridge fittings. This allowed cargo to shift and topple during the heel, worsening the imbalance.

15/x The captain was not present on the bridge during the critical moments of the turn. He returned after the ship began tilting but did not issue clear evacuation orders. Crew members requested guidance via radio, but received no response.

16/x The captain and senior crew evacuated via the bridge wing at 09:48 AM, well before most passengers. Investigators concluded that the captain lacked intent to evacuate passengers and failed in his duty to ensure their safety.

17/x In 2015, Lee was convicted of gross negligence, violation of maritime law, and homicide. He had failed to order evacuation, abandoned command, and made no attempt to assist passengers. The court called it “murder through willful negligence.”

18/18 He was originally sentenced to 36 years, but South Korea’s Supreme Court upgraded the sentence to life imprisonment. It ruled that as captain, Lee had a legal duty under Korean law to ensure passengers’ safety, especially after the vessel began listing.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh