I've had enough.

In this thread, I will tell you, definitively, whether Sydney Sweeney has great jeans.

This way, you will be more informed when shopping for your wardrobe . 🧵

In this thread, I will tell you, definitively, whether Sydney Sweeney has great jeans.

This way, you will be more informed when shopping for your wardrobe . 🧵

I should state two things at the outset.

First, I never comment on womenswear because I don't know anything about it. This thread isn't actually about Sweeney's jeans (sorry, I lied). But in the last few days, I've seen grown men buying American Eagle jeans and I can't abide.

First, I never comment on womenswear because I don't know anything about it. This thread isn't actually about Sweeney's jeans (sorry, I lied). But in the last few days, I've seen grown men buying American Eagle jeans and I can't abide.

Second, while clothing quality matters, it's more important to develop a sense of taste. Buying clothes isn't like shopping for electronics — you don't "max out" specs. It's more like buying coffee — you sample around and identify what notes you like. Develop taste.

In this thread, I will get into the basics of jeans. And then talk about my personal taste.

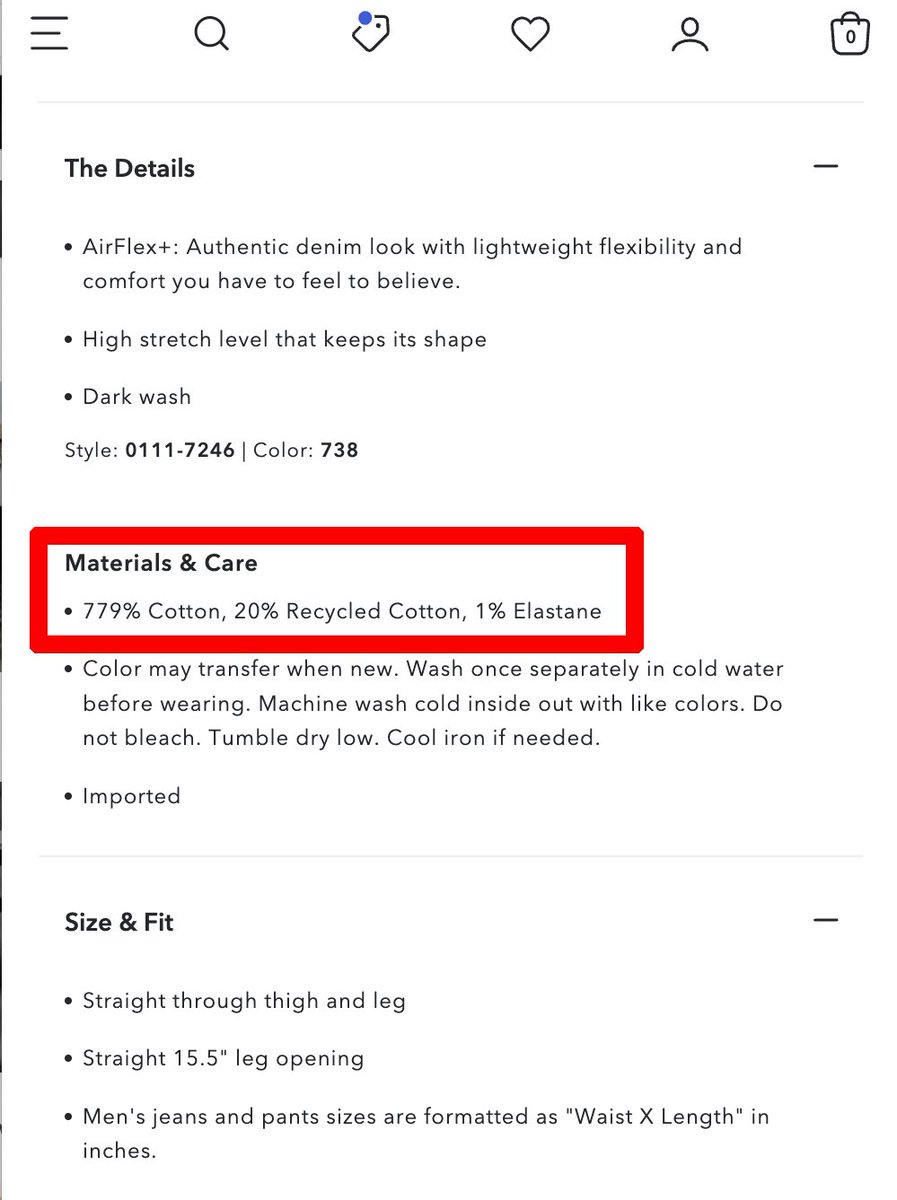

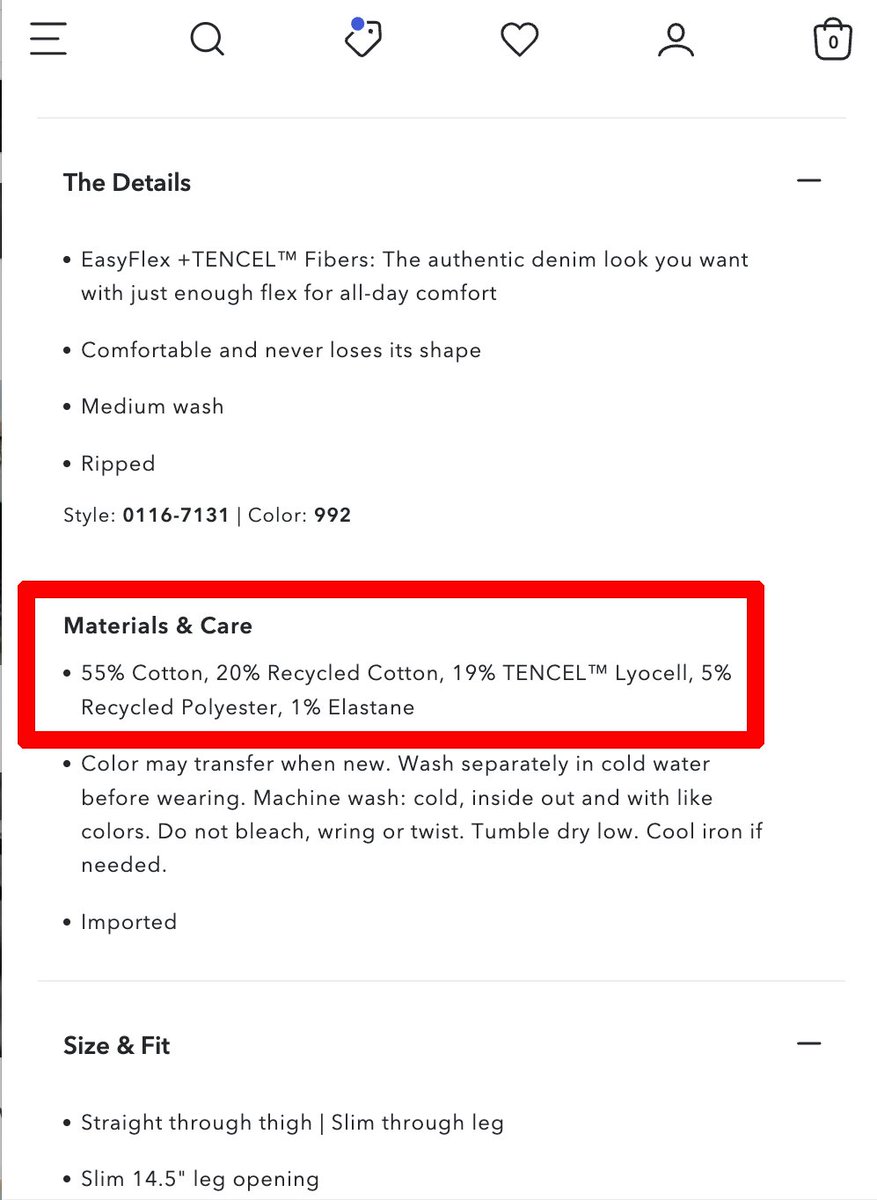

So what makes a pair of jeans "good?" We start with material. American Eagle typically uses blended yarns, such as cotton mixed with recycled cotton, polyester, and elastane.

So what makes a pair of jeans "good?" We start with material. American Eagle typically uses blended yarns, such as cotton mixed with recycled cotton, polyester, and elastane.

Sometimes manufacturers add elastane to skinny jeans to make them more comfy (common in womenswear). But AE even uses it in relaxed cuts.

Why? Because their jeans are cheap & require low-quality material. Recycled fibers are shorter and weaker. Elastane helps them not fall apart

Why? Because their jeans are cheap & require low-quality material. Recycled fibers are shorter and weaker. Elastane helps them not fall apart

Worse still, they can't be easily repaired. Pure cotton jeans can be patched or darned when they develop holes. While you can still do this with elastane-blended jeans, the repair won't hold very long, so the cost is not worth it. The jeans eventually end up in a landfill.

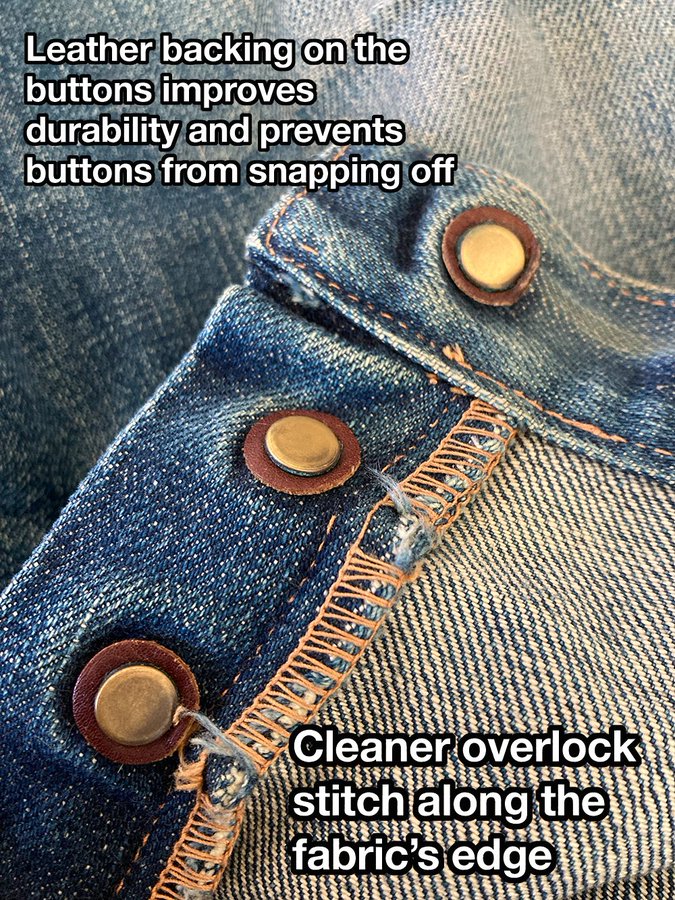

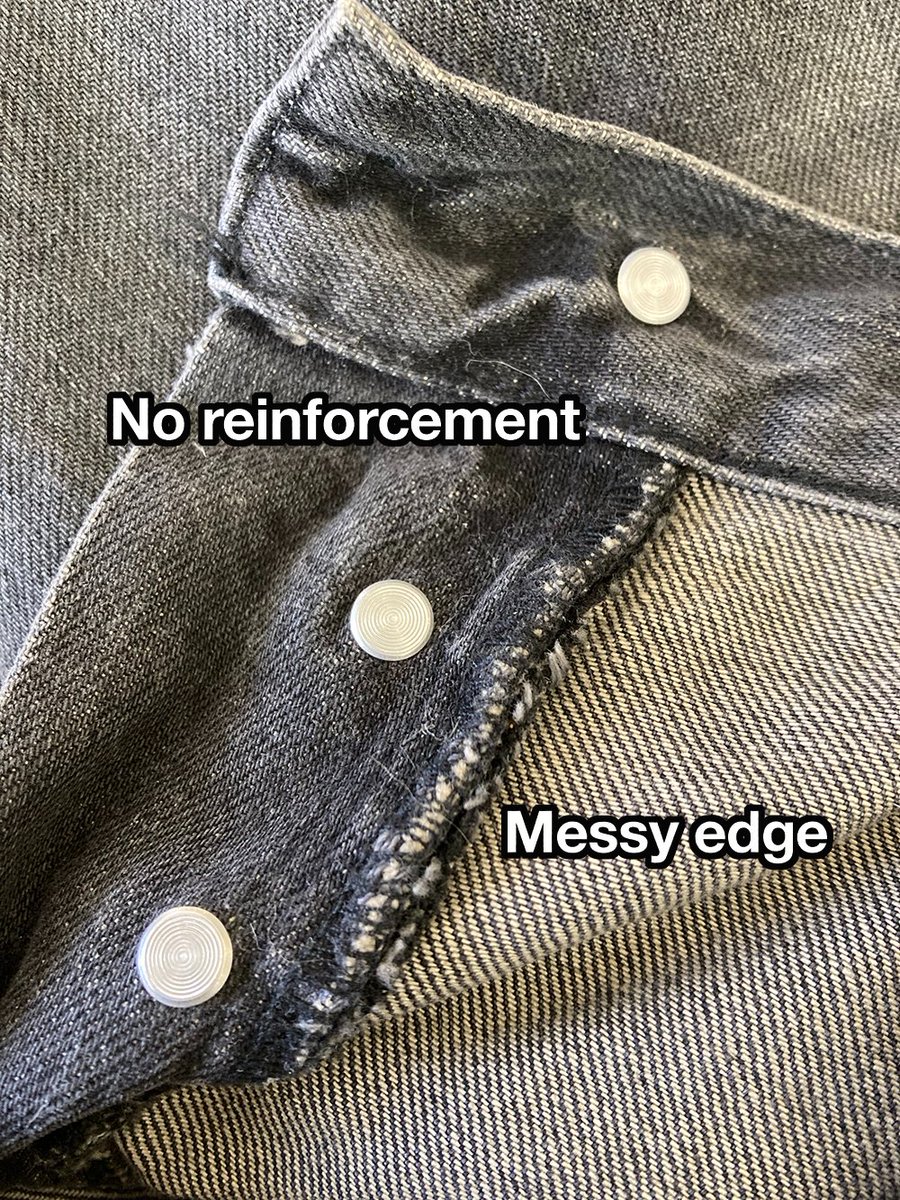

Peer inside and you can spot more cost-cutting. To prevent the raw edges from fraying, AE uses a messy overlock stitch. On a higher-quality pair of jeans, this area (the seat) will be made with a flat-felled seam. This is more labor intensive, but also adds durability.

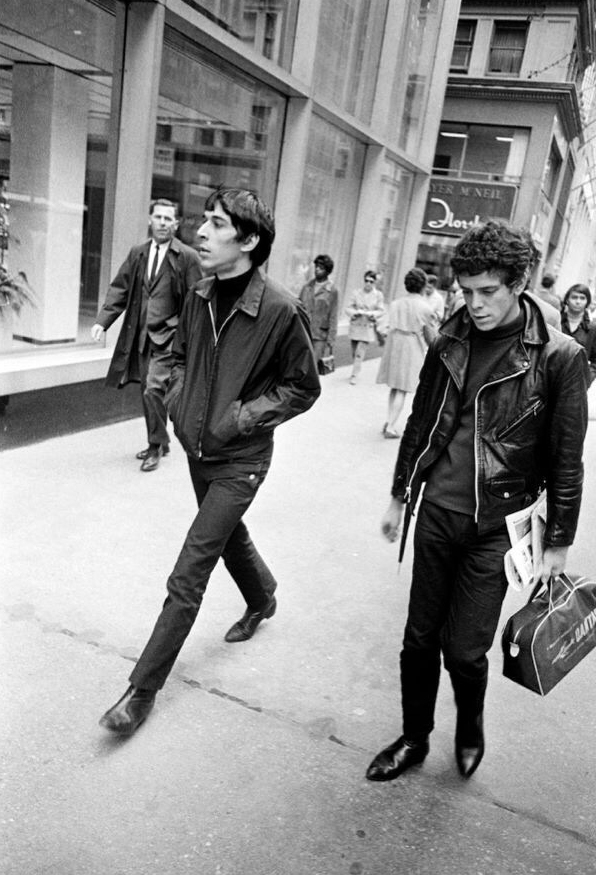

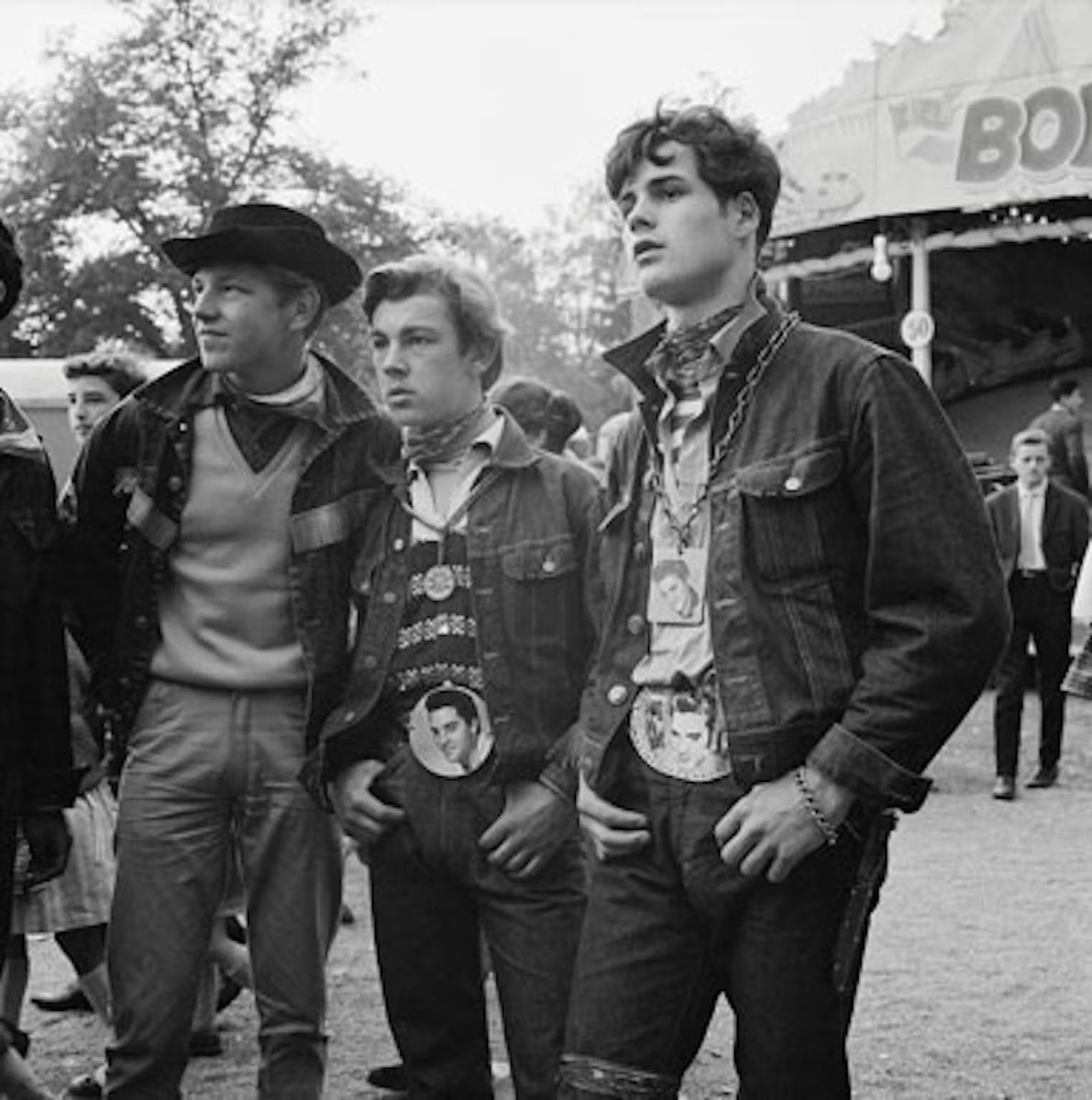

Of course, jeans aren't just about quality — you're buying these to look good. So consider whether the fit and silhouette work for you. Skinny jeans look great with boots and leather jackets bc of rock n roll history. Less good with prep and business casual bc that makes no sense

The above should help you buy a better pair of jeans no matter your taste. But I will now talk about my preferences.

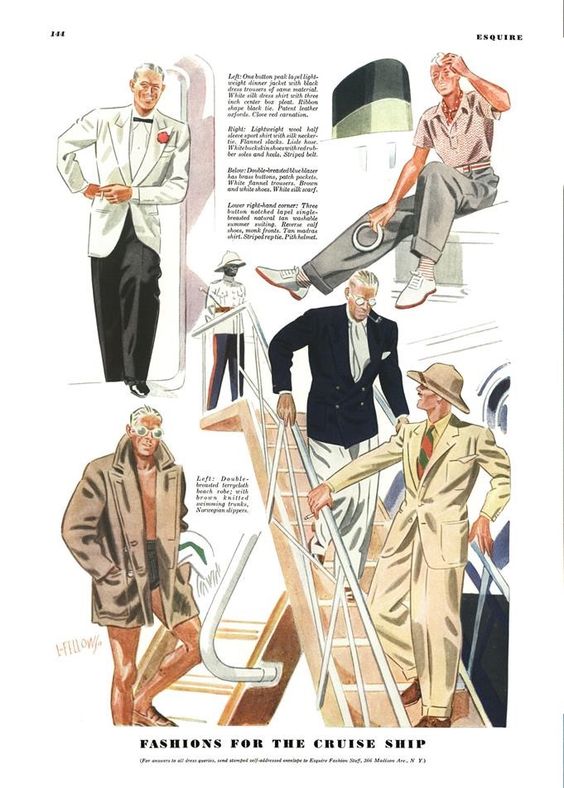

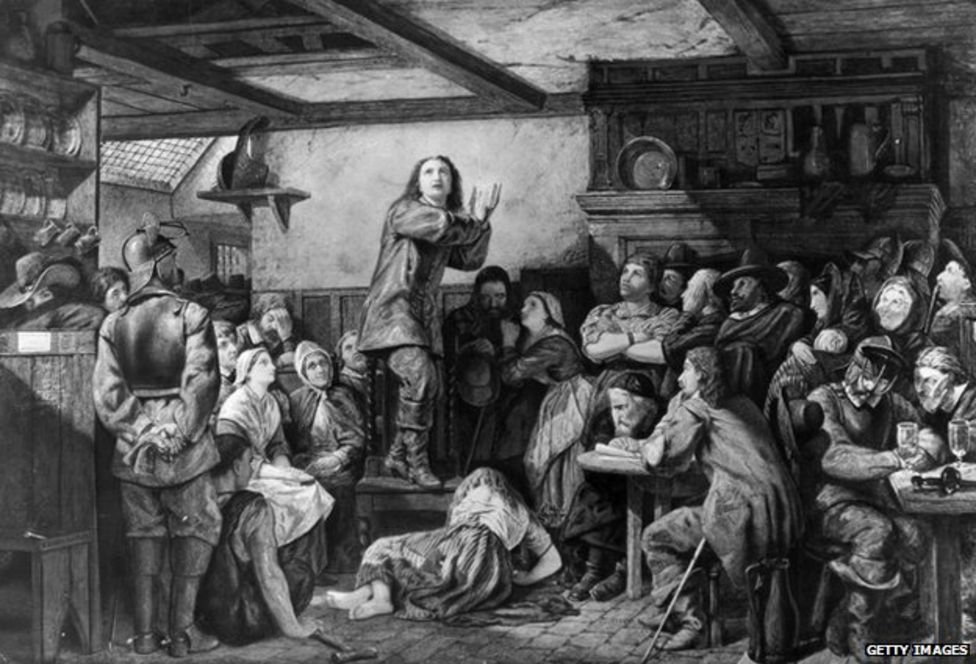

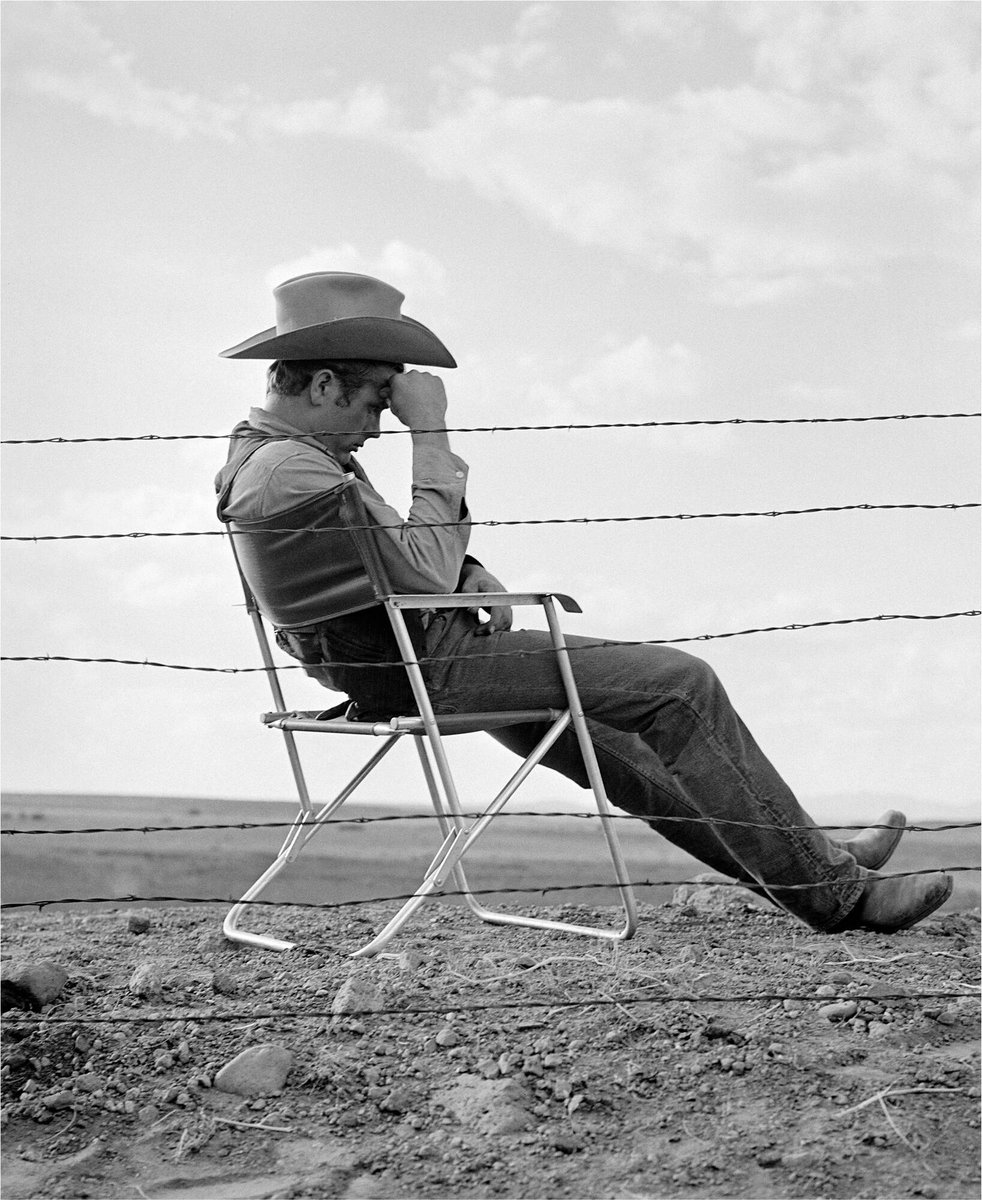

As always, I have presuppositions. Just as I believe men wore tailoring better in the past, I believe the same is true for denim and workwear.

As always, I have presuppositions. Just as I believe men wore tailoring better in the past, I believe the same is true for denim and workwear.

But why did so many men look great in jeans in the past? And why do so many look terrible today?

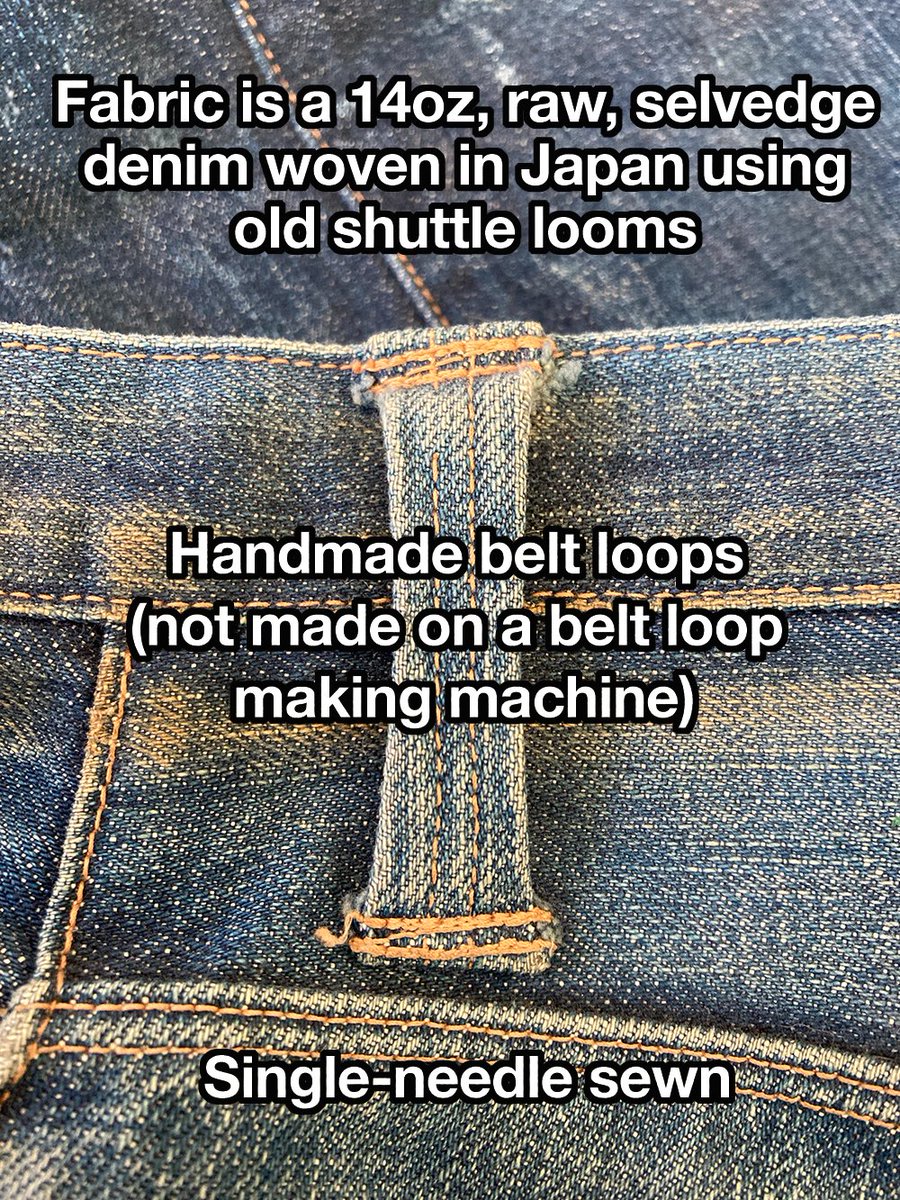

A big change has to do with how denim is woven. For much of the 20th century, denim was woven on shuttle looms, which produce narrower width fabric finished with selvedge (self-edge)

A big change has to do with how denim is woven. For much of the 20th century, denim was woven on shuttle looms, which produce narrower width fabric finished with selvedge (self-edge)

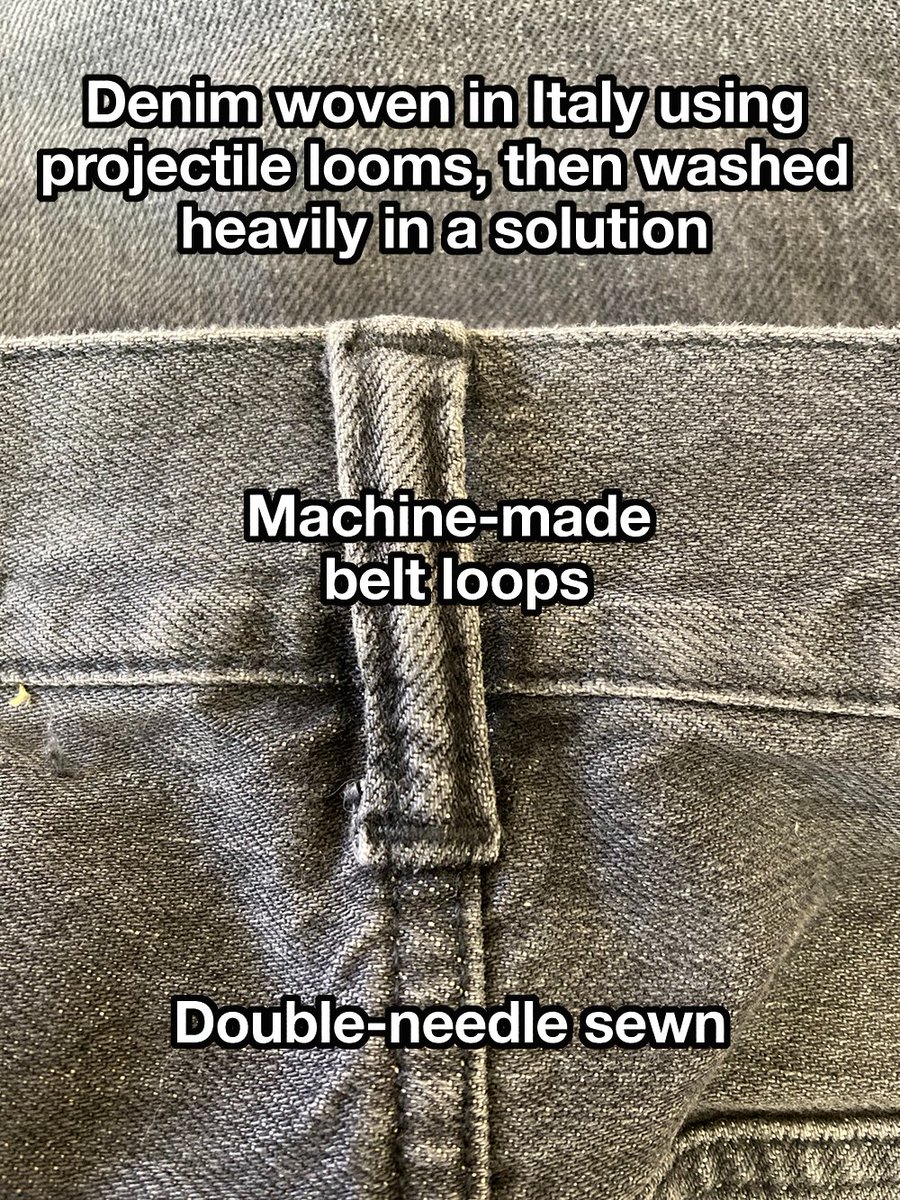

Around the 1970s, denim producers started to use faster, more efficient projectile looms. This was the dawn of mass-manufacturing for denim. By producing things at higher speeds, mills could cut cost and offer lower-priced materials. Of course, brands were happy to adopt.

The other dimension has to do with finishing. When men bought jeans during the first half of the 20th century, they were typically buying raw denim, which is to say that the material was in its "natural state." It was not pre-washed or pre-faded — you put the fades in yourself.

Over time, new finishing processes developed: sanforization (pre-shrinking), mercerization (making the fabric smoother and more lustrous), and of course, pre-distressing. You can find denim today with pre-faded laps and pre-torn knees. Some are even faded with lasers!

Pre-washed jeans are popular today because they're softer and more comfortable out the box. The problem with raw denim is that it can be stiff and cardboard-y at first. The fabric will also bleed for a bit, which means indigo can rub off on your white couch.

But the advantage is that it looks much more natural. The top of the pockets bust because you repeatedly put your hands into your pockets. Fades develop around your actual lap and the back of your knees, not in weird places that don't even match your body.

The older method of producing jeans resulted in a fabric with a lot more character, which yields better looking fades. Once denim moved from shuttle looms to projectile looms, and was put through all sorts of finishes, you've squeezed the life out of it. It's processed baloney.

In the early 1980s, denim brands also moved from chain stitching to the faster, more economical lock stitching. The chain stitch was historically used in certain areas, such as the hem, which resulted in the roping effect you see in the first pic. Without it, the hem is flat.

When you combine these things, you get the differences below. First pic shows vintage Levis (shuttle loom, natural fading, chain stitching). Second pic shows jeans from the mid-1990s, when denim was almost entirely mass produced (projectile loom, pre-washed, lockstitch).

Of course, when you get into the upper tiers of denim, there may be other details that separate a pair of jeans. Stevenson jeans feature leather backed buttons and handmade belt loops (pics 1 and 2). This is a step up from even designer jeans, such as Our Legacy in pics 3 and 4.

My goal is to not push you in any one direction (raw denim may not be your thing!). Only to help you understand the basics of jeans (AE jeans are objectively bad). And give you a sense of how to understand fabric and details so you can find what's right for you. Develop taste!

Whether raw or processed, jeans can be "good" depending on your taste.

If you'd like to explore raw denim, check out stores such as Self Edge, 3sixteen, Standard & Strange, Blue in Green, Division Road, AB Fits, Blue Owl Workshop, Tellason, Rivet & Hide (UK), and Dutil (Canada).

If you'd like to explore raw denim, check out stores such as Self Edge, 3sixteen, Standard & Strange, Blue in Green, Division Road, AB Fits, Blue Owl Workshop, Tellason, Rivet & Hide (UK), and Dutil (Canada).

I also like Buck Mason's Saddle Cut (available in raw denim).

If the prices above take you aback, check Gustin. Their newly introduced "vintage straight" — a roomier, more classic cut — comes in Cone Mills denim.

Todd Shelton and Williamsburg Garment Company can also do custom

If the prices above take you aback, check Gustin. Their newly introduced "vintage straight" — a roomier, more classic cut — comes in Cone Mills denim.

Todd Shelton and Williamsburg Garment Company can also do custom

Many of these companies — such as Tellason, 3sixteen, Gustin, Raleigh Denim, Imogene + Willie — also produce their jeans in the United States. This way, you can support US jobs.

IMO, it's better to buy one pair of high-quality jeans than three pairs of low-quality ones.

IMO, it's better to buy one pair of high-quality jeans than three pairs of low-quality ones.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh