Castles are built to defend against external threats; but what if the enemy lies within?

One castle in Europe is said to serve to host one of the gates to Hell. Do its inward-facing walls and a chapel over a bottomless pit make it a fortress against demons? ..🧵⤵️

One castle in Europe is said to serve to host one of the gates to Hell. Do its inward-facing walls and a chapel over a bottomless pit make it a fortress against demons? ..🧵⤵️

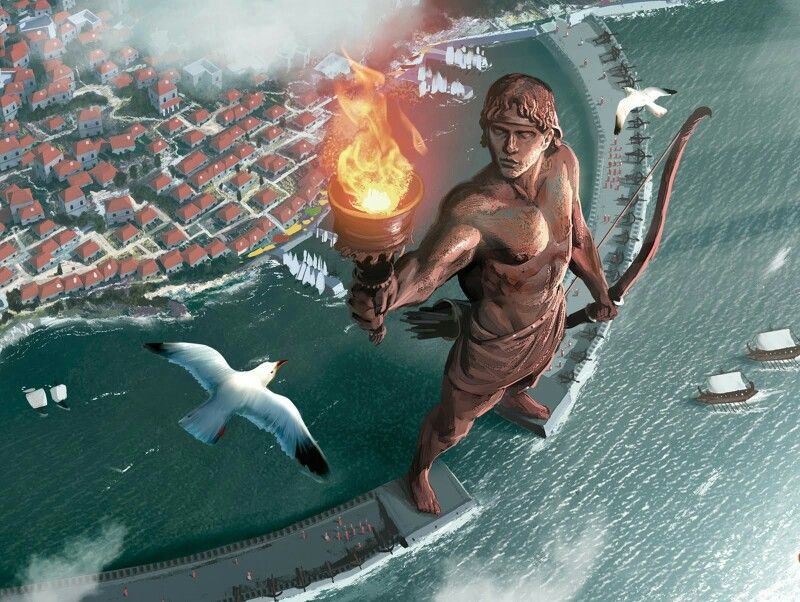

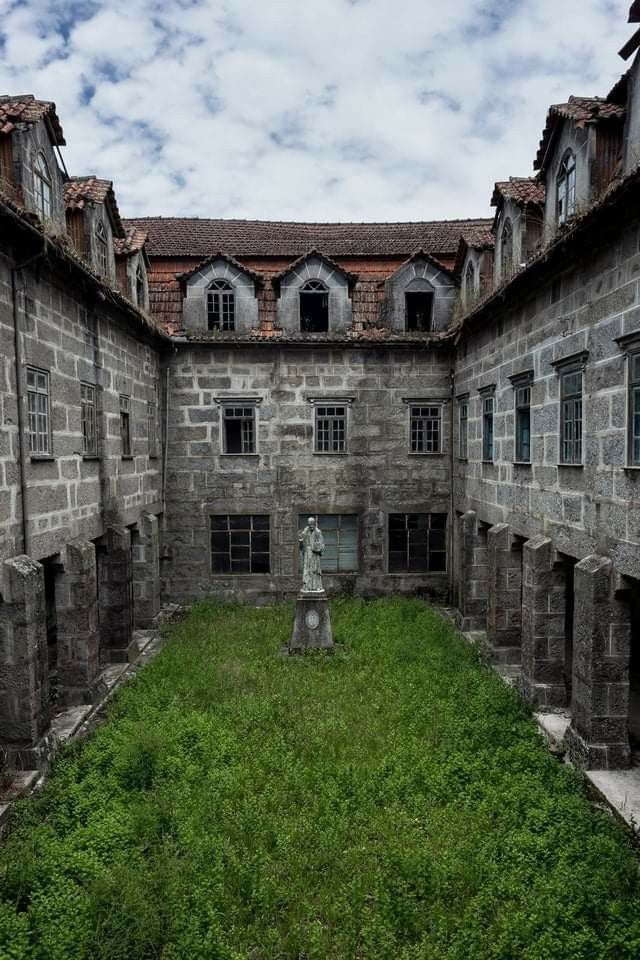

Perched on a limestone cliff 47 kilometers north of Prague, this 13th-century Gothic fortress defies the logic of its era. It wasn’t built to guard a trade route, house royalty, or fend off invaders.

According to local legend, Houska was erected for a far darker purpose: to seal a gaping chasm beneath its chapel, a pit whispered to be a gateway to Hell itself, spewing demons into the night.

But is this medieval stronghold truly a bulwark against the infernal, or is its sinister reputation a tapestry of fear and folklore woven over centuries?

But is this medieval stronghold truly a bulwark against the infernal, or is its sinister reputation a tapestry of fear and folklore woven over centuries?

Built between 1253 and 1278, likely under the reign of Bohemian king Ottokar II, Houska Castle breaks every rule of medieval architecture. Most castles of the era were strategic fortresses, bristling with outward-facing walls to repel enemies. Houska, however, turns inward.

Its fortifications—thick stone walls, arrow slits, and battlements—face the courtyard, as if the threat lurked within. No kitchen graces its halls, no reliable water source sustains it beyond a rainwater cistern.

Stranger still, many of its “windows” are illusions, glass panes backed by solid stone, casting an eerie glow that hints at secrets sealed within.

Stranger still, many of its “windows” are illusions, glass panes backed by solid stone, casting an eerie glow that hints at secrets sealed within.

Historical records state Houska served as an administrative hub for royal estates, a practical function for a remote outpost. Yet its isolation, far from trade routes or settlements, raises questions.

Why build a castle in such an inhospitable spot, with defenses poised to trap something inside? The answer, locals claim, lies beneath the castle’s Gothic chapel, where a bottomless pit yawns into the earth.

Why build a castle in such an inhospitable spot, with defenses poised to trap something inside? The answer, locals claim, lies beneath the castle’s Gothic chapel, where a bottomless pit yawns into the earth.

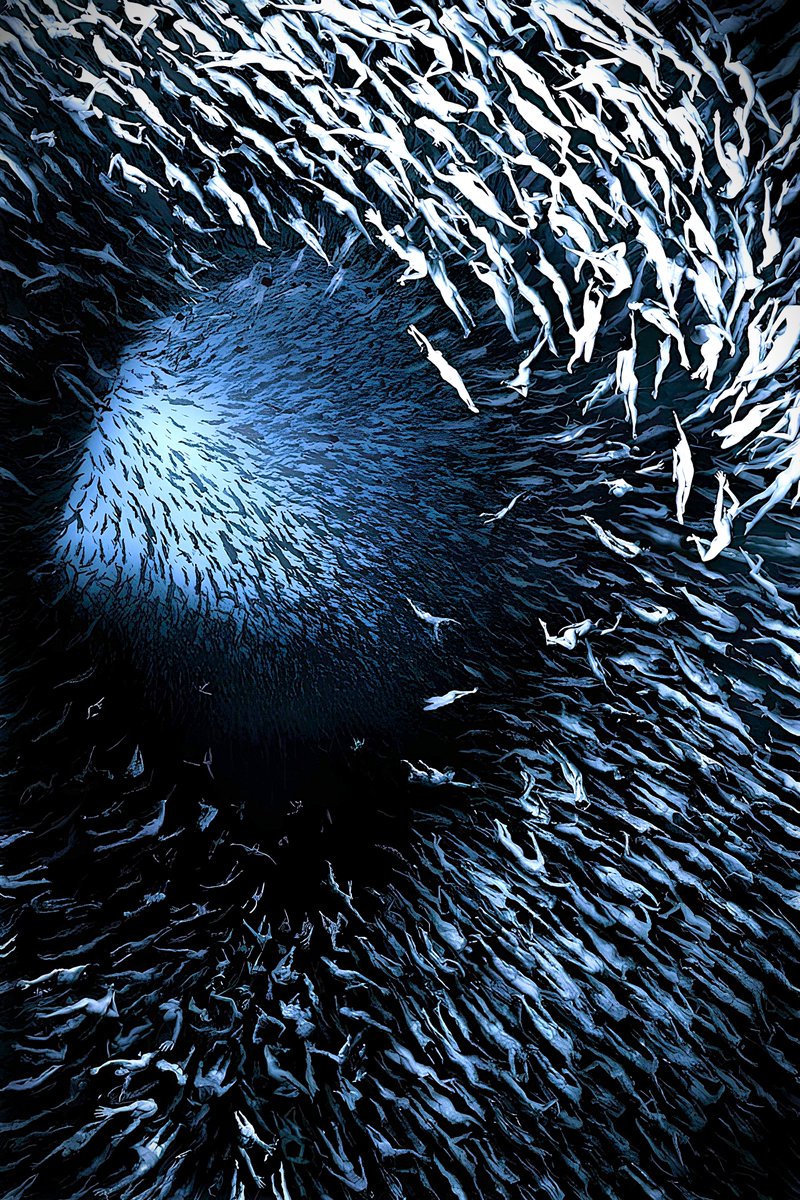

The legend begins with a chasm, a jagged wound in the limestone said to predate the castle. Villagers spoke of horrors emerging at dusk: winged creatures with glowing eyes, half-human beasts that skittered through the forest, and a pervasive dread that choked the air.

Attempts to fill the pit with stones failed; it swallowed everything, earning the name “the gateway to Hell.”

Attempts to fill the pit with stones failed; it swallowed everything, earning the name “the gateway to Hell.”

In a chilling tale, prisoners facing execution were offered a grim bargain: descend into the pit and report what they saw for a chance at freedom. One man, lowered by rope, lasted mere moments before screaming in terror.

When hauled up, his hair had turned white, his mind shattered. He babbled of writhing shadows and clawed hands before dying days later. Others met similar fates, their stories fueling the myth.

When hauled up, his hair had turned white, his mind shattered. He babbled of writhing shadows and clawed hands before dying days later. Others met similar fates, their stories fueling the myth.

To contain this evil, the castle’s chapel was built directly over the pit, dedicated to the Archangel Michael, the biblical warrior against darkness. Its walls bear unsettling frescoes: a left-handed centaur, a symbol of malevolence in medieval lore; dragons writhing in chains; and demons pierced by divine arrows.

This inward-facing design fuels the castle’s dark legend. Locals whisper that the fortifications were built to trap demonic entities emerging from a bottomless pit beneath the chapel, a “gateway to Hell” that demanded containment over conquest.

The arrow slits, positioned to fire into the courtyard, suggest a garrison prepared to battle otherworldly horrors rather than human foes. The barred interior gates evoke a prison more than a palace, as if the castle’s own halls were a labyrinth to confine something malevolent.

The arrow slits, positioned to fire into the courtyard, suggest a garrison prepared to battle otherworldly horrors rather than human foes. The barred interior gates evoke a prison more than a palace, as if the castle’s own halls were a labyrinth to confine something malevolent.

Visitors today report eerie phenomena—scratching and clawing from beneath the chapel floor, whispers in empty corridors, and a suffocating sense of being watched. Is the pit truly a portal to the underworld, or a natural anomaly that sparked medieval imaginations?

Houska’s documented history offers clues but no clear answers. After Ottokar II, the castle passed through noble families, was remodeled in Renaissance style (1584–1590), and fell into ruin until the 19th century. It’s now a tourist site, owned by descendants of Josef Šimonek, former Škoda president.

Yet darker chapters linger in its lore. In the 1630s, a Swedish occultist named Oronto allegedly used the castle for experiments to cheat death, terrifying locals until they assassinated him. This tale, vivid as it is, lacks historical records and may be a later embellishment.

More tangible is Houska’s occupation by the Germans during World War II (1943–1945). Known for their fascination with the occult, reportedly saw Houska as a site of mystical power.

Locals recalled strange lights flickering in the castle at night and unearthly noises echoing through the forest.

Locals recalled strange lights flickering in the castle at night and unearthly noises echoing through the forest.

After the war, unmarked graves and landmines were found nearby, hinting at secretive activities. Were they conducting occult experiments, as some claim, or simply using the castle as a wartime base?

Destroyed records leave only speculation, and the graves could reflect mundane wartime casualties rather than supernatural pursuits.

Destroyed records leave only speculation, and the graves could reflect mundane wartime casualties rather than supernatural pursuits.

Houska’s reputation as a paranormal hotspot endures. Visitors report chilling encounters: a headless figure in the courtyard, blood streaming from its neck; a spectral White Lady weeping in the halls; a demonic hound that vanishes with a whiff of sulfur.

Paranormal investigators, drawn by these tales, have featured Houska in shows like Ghost Hunters International (2009) and Most Haunted Live (2010).

Paranormal investigators, drawn by these tales, have featured Houska in shows like Ghost Hunters International (2009) and Most Haunted Live (2010).

Its legend even inspired the Doctor Who graphic novel Herald of Madness (2019). Yet no physical evidence confirms the pit’s depth or demonic activity. The “bottomless” chasm could be a karst sinkhole, common in Bohemia’s limestone terrain, possibly emitting gases that fueled tales of otherworldly horrors.

Skeptics argue Houska’s legend is a product of its time. In the Middle Ages, unexplained natural phenomena—caves, gas vents, or seismic rumbles—were often attributed to the devil.

The chapel’s demonic imagery and dedication to Michael suggest a religious effort to quell local fears, casting the pit as a spiritual rather than literal threat.

The chapel’s demonic imagery and dedication to Michael suggest a religious effort to quell local fears, casting the pit as a spiritual rather than literal threat.

The castle’s inward defenses might reflect symbolic design or practical quirks, not a demonic siege. Yet the absence of clear answers keeps the mystery alive.

Why build a castle with no apparent purpose in such a desolate spot? Could the pit, even if natural, have inspired such dread that a fortress was erected to contain it?

Why build a castle with no apparent purpose in such a desolate spot? Could the pit, even if natural, have inspired such dread that a fortress was erected to contain it?

Stand in the chapel, gaze at the frescoes, and listen for the faint scratching below. Is it the wind, a trick of the mind, or something older, hungrier, stirring in the dark?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh