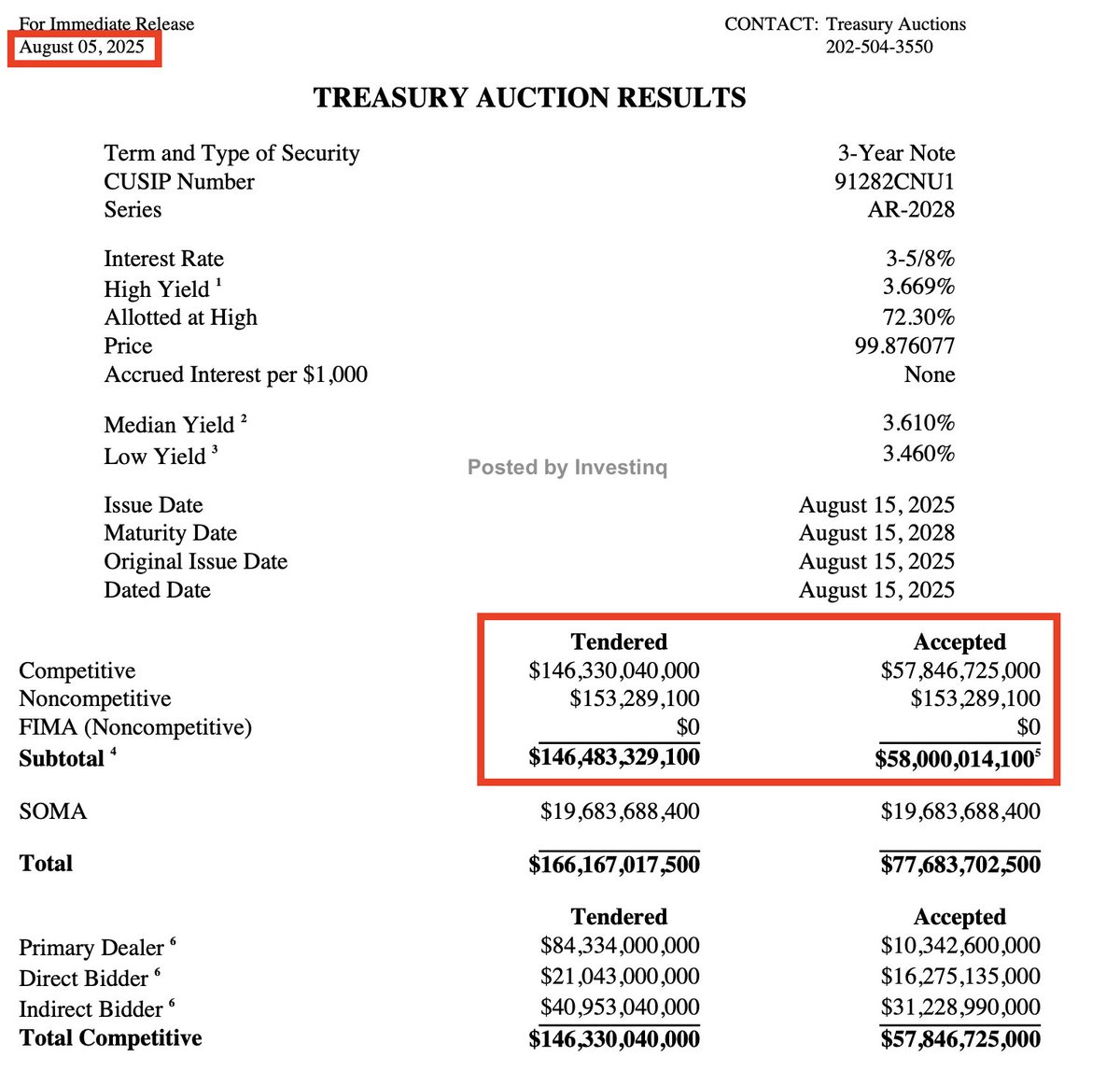

🚨 The U.S. tried to raise $58 billion and demand came in cold.

Foreign demand hit a low, and big banks had to step up.

Here’s what happened and why it matters for everyone.

(a thread)

Foreign demand hit a low, and big banks had to step up.

Here’s what happened and why it matters for everyone.

(a thread)

When the U.S. government needs money (which is always), it borrows by selling promises to pay back later called Treasuries.

These are basically IOUs with interest.

In this case, it sold 3-year notes meaning the U.S. will repay buyers in 3 years, with interest.

These are basically IOUs with interest.

In this case, it sold 3-year notes meaning the U.S. will repay buyers in 3 years, with interest.

These notes are sold at auctions like eBay, but for debt.

Investors tell the government what interest rate they want in order to lend.

The government picks the best offers (lowest rates) until it raises the full $58 billion.

Investors tell the government what interest rate they want in order to lend.

The government picks the best offers (lowest rates) until it raises the full $58 billion.

But everyone who wins the auction gets the same rate, the highest rate accepted.

That’s called the stop-out yield, think of it like the final price the government had to offer to get the money.

That’s called the stop-out yield, think of it like the final price the government had to offer to get the money.

Now, the market guesses what that rate will be before the auction happens.

This guess is called the “when-issued yield” sort of like the betting odds.

In this case, the market expected the auction to close at 3.662%.

This guess is called the “when-issued yield” sort of like the betting odds.

In this case, the market expected the auction to close at 3.662%.

Instead, the actual result was 3.669%.

That 0.007% difference is called a “tail.”

It means demand was weaker than expected, the government had to pay investors a little more to get them to buy.

That 0.007% difference is called a “tail.”

It means demand was weaker than expected, the government had to pay investors a little more to get them to buy.

There are 3 types of buyers at these auctions:

• Indirect bidders – mostly foreign governments and global investors

• Direct bidders – U.S. pensions, hedge funds, and investment firms

• Primary dealers – big banks that must buy whatever’s left

• Indirect bidders – mostly foreign governments and global investors

• Direct bidders – U.S. pensions, hedge funds, and investment firms

• Primary dealers – big banks that must buy whatever’s left

Here’s who showed up this time:

• Foreign buyers took 54%, their lowest share in over a year

• U.S. investors (directs) took 28% near record high

• Big banks got stuck with 18% not great

• Foreign buyers took 54%, their lowest share in over a year

• U.S. investors (directs) took 28% near record high

• Big banks got stuck with 18% not great

Why are foreign investors backing off? Start with currency risk.

If you’re in Japan or Europe and buy U.S. bonds, the value can swing based on the dollar.

To protect themselves, these buyers “hedge” basically buying insurance.

If you’re in Japan or Europe and buy U.S. bonds, the value can swing based on the dollar.

To protect themselves, these buyers “hedge” basically buying insurance.

But that “insurance” is very expensive right now so expensive that it wipes out the profit they’d make from buying U.S. bonds.

In some cases, they’d earn close to zero.

So they’re saying: “not worth it.”

In some cases, they’d earn close to zero.

So they’re saying: “not worth it.”

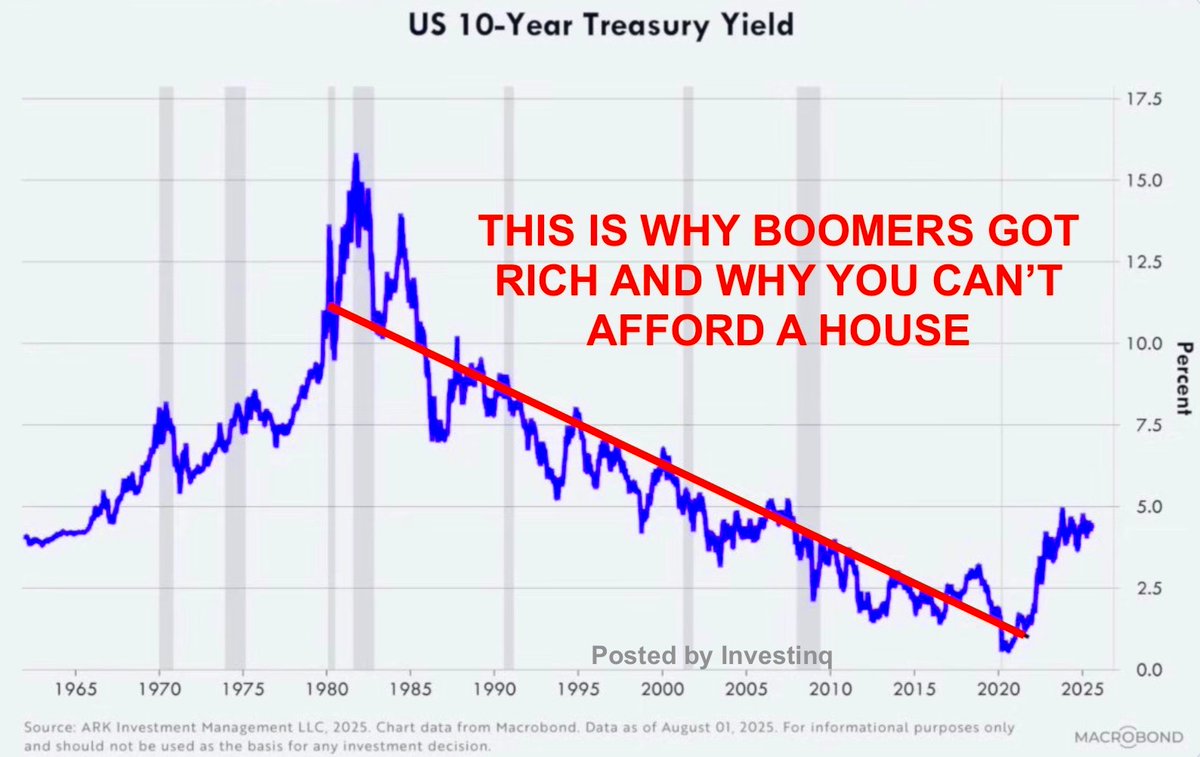

Also, interest rates around the world are rising.

A few years ago, U.S. bonds were the best deal around. Now? You can earn 2–3% at home in Japan or Europe with less hassle.

The U.S. is no longer the only game in town.

A few years ago, U.S. bonds were the best deal around. Now? You can earn 2–3% at home in Japan or Europe with less hassle.

The U.S. is no longer the only game in town.

Then there’s politics.

Some countries (like China) are slowly moving away from U.S. debt for strategic reasons.

They’re buying less and investing elsewhere in gold, euros, or domestic projects. It’s part of a long-term shift.

Some countries (like China) are slowly moving away from U.S. debt for strategic reasons.

They’re buying less and investing elsewhere in gold, euros, or domestic projects. It’s part of a long-term shift.

So if foreigners are stepping back… who’s stepping in?

U.S. investors. Pensions, insurance companies, and hedge funds filled the gap.

In this auction, direct bidders (mostly U.S.-based) took nearly 30%, nearly record high.

U.S. investors. Pensions, insurance companies, and hedge funds filled the gap.

In this auction, direct bidders (mostly U.S.-based) took nearly 30%, nearly record high.

But not all demand is equal.

Some of these U.S. buyers are hedge funds doing “basis trades.”

That’s a fancy term for borrowing money cheaply, buying bonds, and trying to make small profits from pricing differences.

Some of these U.S. buyers are hedge funds doing “basis trades.”

That’s a fancy term for borrowing money cheaply, buying bonds, and trying to make small profits from pricing differences.

It’s not long-term investing, it’s fast, highly-leveraged trading.

If that trade stops working, they’ll leave.

So this demand is fragile, it can vanish quickly if conditions change.

If that trade stops working, they’ll leave.

So this demand is fragile, it can vanish quickly if conditions change.

Big banks (called primary dealers) are always required to bid.

They act as a backstop but if they’re getting stuck with more bonds at each auction, they’ll eventually demand higher yields to keep buying.

That’s how borrowing gets more expensive.

They act as a backstop but if they’re getting stuck with more bonds at each auction, they’ll eventually demand higher yields to keep buying.

That’s how borrowing gets more expensive.

This auction’s bid-to-cover ratio was 2.53.

That means: for every $1 the government wanted to borrow, $2.53 was offered.

Sounds healthy but remember, it matters who’s bidding, not just how much.

That means: for every $1 the government wanted to borrow, $2.53 was offered.

Sounds healthy but remember, it matters who’s bidding, not just how much.

Also: investors paid $99.88 for a bond worth $100 at maturity.

That small discount, plus the 3.875% interest rate (coupon), is their return.

There’s no "back interest" because this is a brand-new bond.

That small discount, plus the 3.875% interest rate (coupon), is their return.

There’s no "back interest" because this is a brand-new bond.

So, what happened after? Well, despite the weak 3-year demand… the 10-year yield didn’t move much staying around 4.20%.

Why? Because the market already expected this weak auction.

And everyone’s watching the Federal Reserve instead.

Why? Because the market already expected this weak auction.

And everyone’s watching the Federal Reserve instead.

Here’s why the 3-year yield is falling: Short-term bonds react strongly to Fed policy.

And markets now believe the Fed is going to start cutting interest rates soon maybe as early as September.

So investors are piling into 3-year bonds, pushing yields lower.

And markets now believe the Fed is going to start cutting interest rates soon maybe as early as September.

So investors are piling into 3-year bonds, pushing yields lower.

But longer-term bonds like the 10-year, 20-year, and 30-year are different.

They reflect big-picture expectations: inflation, economic growth, and long-term debt risks.

Investors still see value there, so demand has stayed relatively steady… for now.

They reflect big-picture expectations: inflation, economic growth, and long-term debt risks.

Investors still see value there, so demand has stayed relatively steady… for now.

So what happens if this trend continues?

If this week’s 10-year auctions are also weak, it’ll be a much bigger deal.

It means investors are stepping back from all maturities not just the short ones.

If this week’s 10-year auctions are also weak, it’ll be a much bigger deal.

It means investors are stepping back from all maturities not just the short ones.

And when demand fades, the U.S. has to offer higher interest rates to attract buyers.

That raises borrowing costs for the government.

And for you.

That raises borrowing costs for the government.

And for you.

Why does this matter for regular people? Because Treasury yields influence:

• Mortgage rates

• Car loans

• Credit cards

• Student loans

• Even stock prices

If government borrowing costs rise, yours probably will too.

• Mortgage rates

• Car loans

• Credit cards

• Student loans

• Even stock prices

If government borrowing costs rise, yours probably will too.

All eyes are now on the 10-year bond auction happening this week.

It’s a bigger test, with more long-term implications. I’ll be watching that closely and so should you.

Because if demand slips there too, the ripple effects won’t be subtle.

It’s a bigger test, with more long-term implications. I’ll be watching that closely and so should you.

Because if demand slips there too, the ripple effects won’t be subtle.

If you found these insights valuable: Sign up for my FREE newsletter! thestockmarket.news

I hope you've found this thread helpful.

Follow me @_Investinq for more.

Like/Repost the quote below if you can:

Follow me @_Investinq for more.

Like/Repost the quote below if you can:

https://x.com/_investinq/status/1952812947232698835?s=46

This is an update for the 10 year auction that happened today!

https://twitter.com/_investinq/status/1953177636819075565

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh