Indian banks just reported Q1FY26 results. Nothing blew us away, no surprises, no drama. But if you zoom out just a bit, the bigger picture starts to look... well, a little bleak. The sector has been quietly sliding, not falling off a cliff, but steadily losing its shine.🧵👇

Today, the banking sector looks like it's walking on thin ice. It's easy to be caught off-guard by these results if you haven't been paying attention. Over the last few quarters, banks have been walking a tightrope, and this quarter shows why.

If you're betting on a bank, you're basically betting that it'll keep giving out more loans and making money on them. That's the simplest way to gauge whether a bank is growing, check how much new credit it's disbursing. And that number is not great.

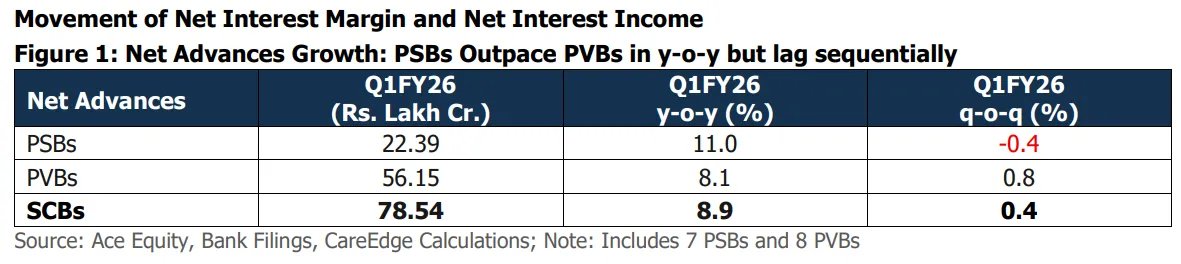

Credit growth across the entire banking system has been steadily slowing for several quarters now. In Q1FY26, overall loan growth came in at just 8.9% YoY. Private sector banks grew slow at 8.1%, while public sector banks were surprisingly stronger at 11%.

Why the divergence? Public banks went all-in on priority sector lending, MSMEs, agriculture, rural loans, sectors that often find it hard to get credit in recession-like situations. These are sectors the government often nudges PSBs to support.

Private banks, on the other hand, stayed cautious on these sectors. They focused on protecting margins rather than chasing loan volume. So PSBs played the volume game, while PVBs played the margin game.

A big part of the slowdown is because large industries aren't borrowing. India's private sector has not been spending a lot on capital expenditure. Lending for large infrastructure projects has been cooling too. Big companies are either flush with cash or hitting the bond market directly.

But while large borrowers are pulling back, MSMEs seem to be stepping up. There's a visible shift toward lending to small and medium enterprises, thanks to government push, formalisation efforts, and credit guarantee schemes like ECLGS and CGTMSE.

However, there's a nuance in this trend, lending to MSMEs may have increased in value, but decreased in volume. That is, only the bigger MSMEs may be getting large-ticket loans, while smaller SMEs are starved for credit.

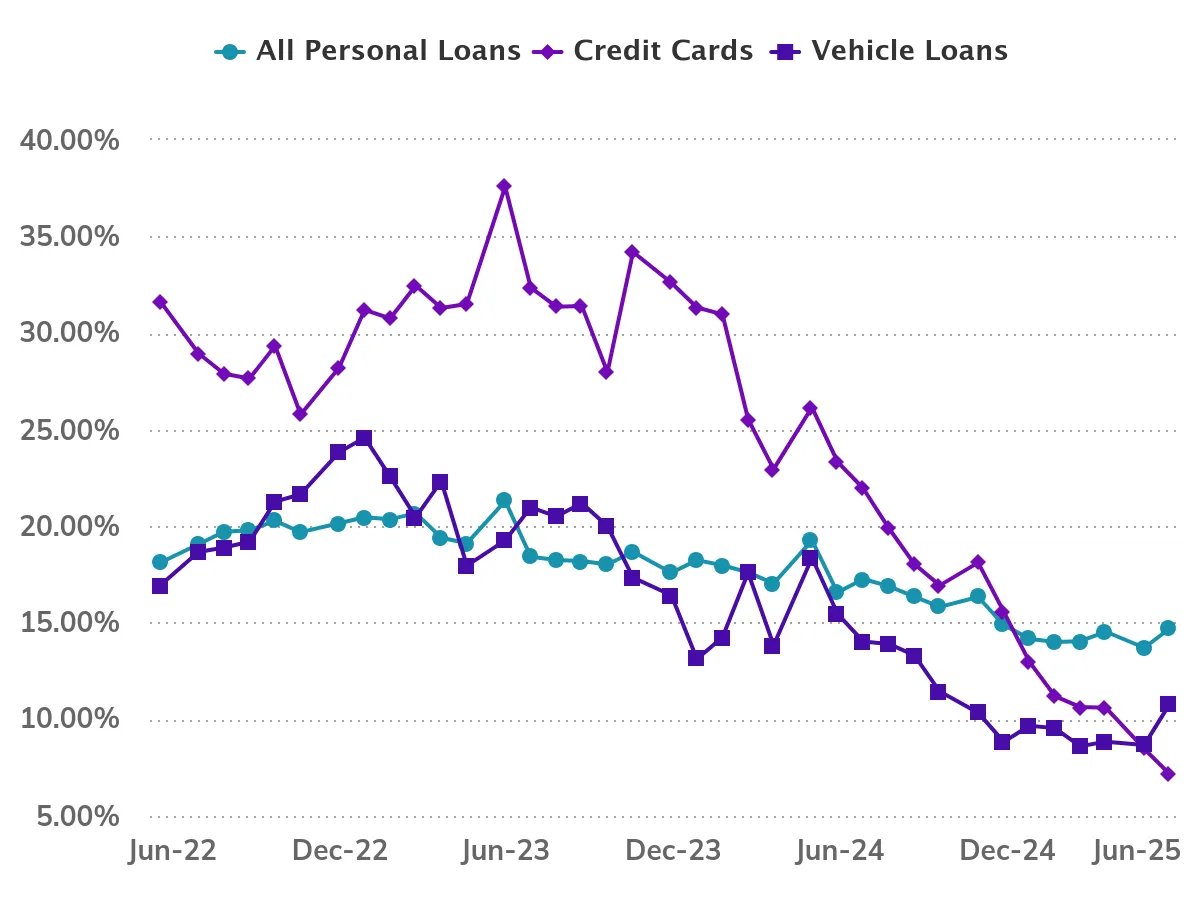

Another drag on banks' growth has been unsecured personal loans, loans offered without taking any collateral. Credit cards, personal loans, vehicle loans, all are showing signs of a cool-off. It's more about banks pulling back after a rise in loan stress.

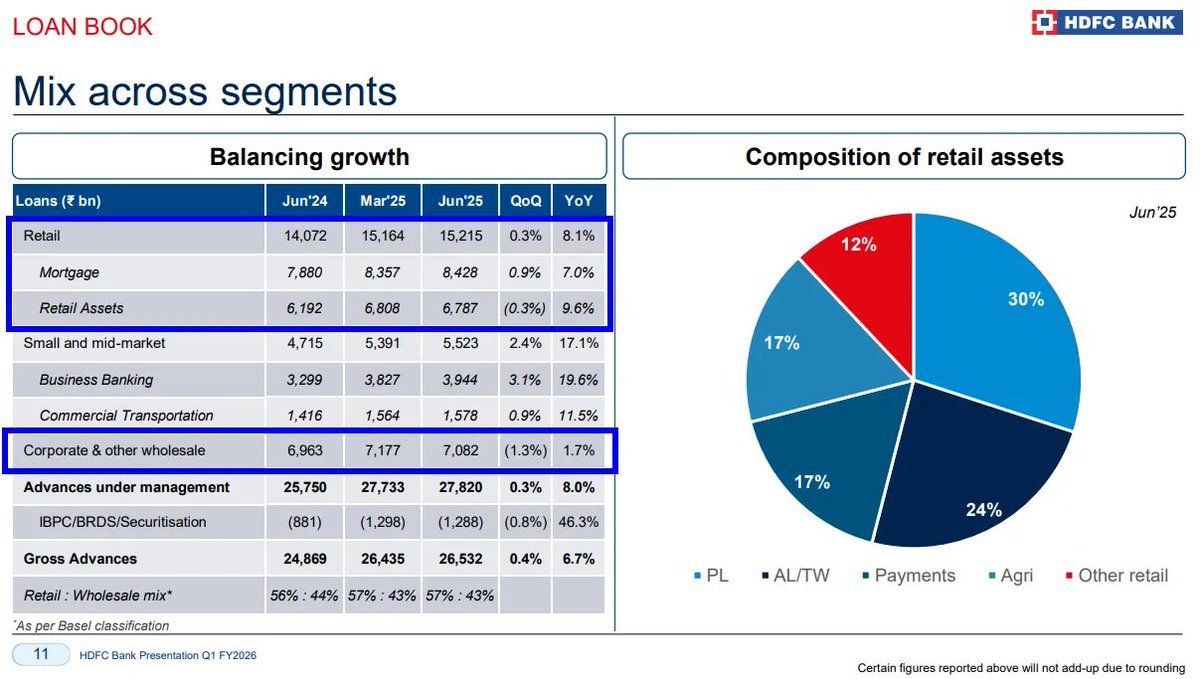

Let's talk specific banks. HDFC Bank saw corporate loans remain flat, retail loans recorded just single-digit growth of 8%. The only real, double-digit growth came from small and medium businesses, which is still a small part of the book.

ICICI Bank's story doesn't change much. Corporate and retail growth was tepid, but SME-focused "business banking" grew 30% YoY. Kotak is a bit of an outlier, its consumer banking book grew 16%, total advances rose 14%, much faster than industry average.

If slowing credit growth wasn't enough, banks are now hurting with shrinking margins. Net Interest Margin for the entire system dropped to 3.24%, the lowest in at least two to three years. Why are margins falling? The answer is pretty intuitive.

Earlier this year, the RBI cut repo rates by a full 1%. Most loans today are linked to external benchmarks like the repo. That means banks were forced to lower lending rates almost immediately. But here's the catch, deposit rates didn't fall as fast.

So banks were still paying depositors almost the same high rate, while earning a lot less from borrowers. A perfect recipe for margin compression. Public sector banks saw bigger margin drops compared to private banks because they're lending to lower-yielding priority sectors.

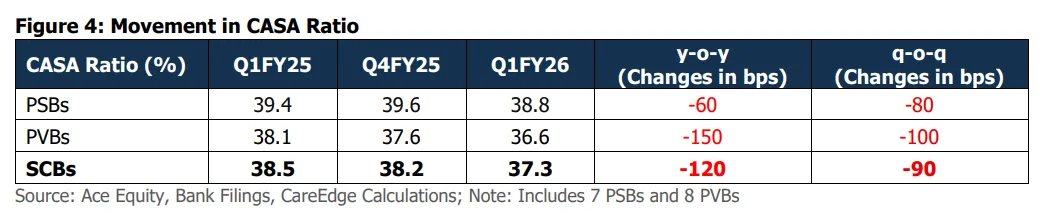

There's another reason margins are under pressure, CASA (Current Account Savings Account) ratios are falling. People have been moving money out of savings accounts into higher-return options like term deposits or mutual funds. Banks are now relying more on expensive sources of funds.

After all that bad news on credit growth and margins, you might wonder, banks would have reported depressing profit growth rates. Honestly, the results would have been even worse, had it not been for treasury gains.

In Q1FY26, treasury income acted like a floatie keeping banks above water. On average, treasury income made up 0.40% of total assets, up from just 0.16% a year ago. For public sector banks, treasury income more than doubled, for private banks, it nearly tripled.

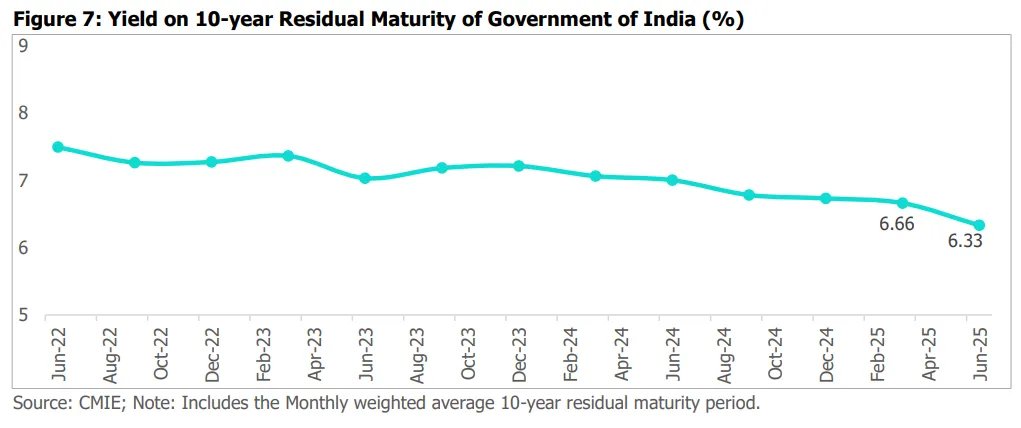

This windfall came because bond yields dropped sharply, the 10-year yield fell 0.33% in the June quarter. But this kind of income isn't sustainable. The RBI has now moved from "cutting" mode to "liquidity absorption" mode, translation, bond yields may not fall further.

So should you still bet on banks? Look, banks didn't report a disaster this quarter, but that's exactly why this quarter is so important. It looks fine on the surface, but under the hood, there may be serious cracks. This is the kind of quarter that keeps you guessing.

We cover this and one more interesting story in today's edition of The Daily Brief. Watch on YouTube, read on Substack, or listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

All links here:thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/whats-going-…

All links here:thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/whats-going-…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh