Southern wages are a tenth of Northern wages for the same work. Even if labor is siloed behind national borders, why don't terms of trade adjust to equalize the price of equivalent work across countries over time? 1/

This is from the stunning paper by @jasonhickel et al. (2024) in Nature. They show that the Global North appropriates more three-quarters of a trillion hours of work from the Global South every year. 👀 2/

This is a great anomaly. In supplementary info, they mention the explanation offered by Arthur Lewis. 3/

Lewis argued that in economies with a large subsistence sector, wages in the modern sector are not determined by productivity in that sector, but rather by the wage floor set in the subsistence economy. 4/

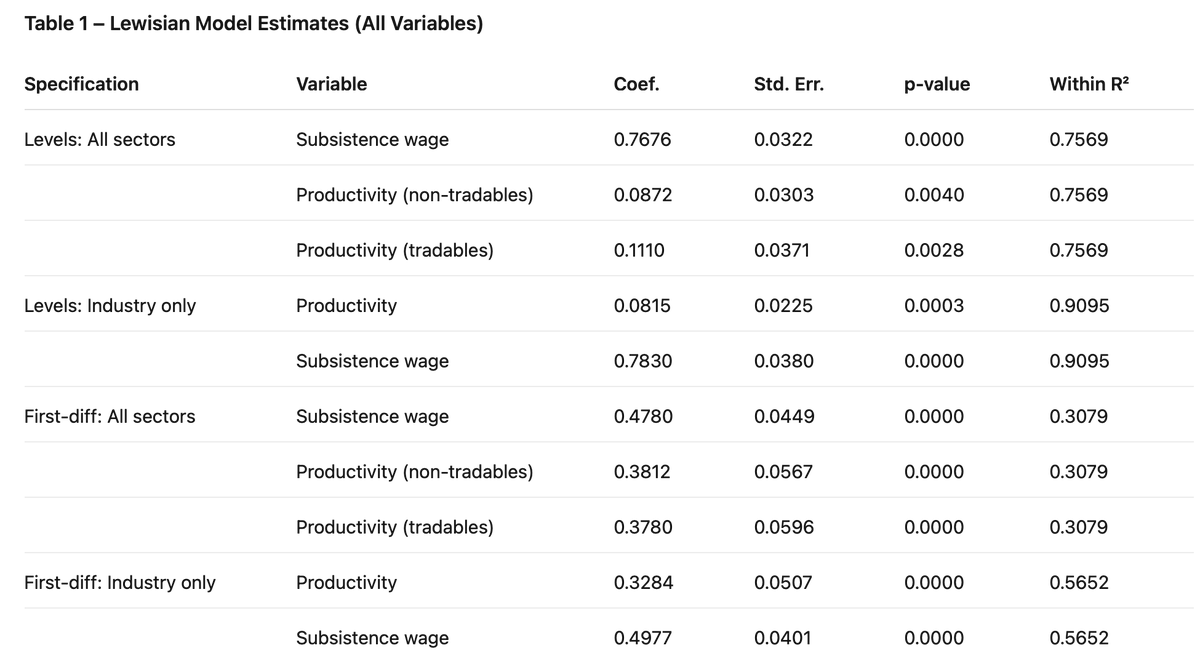

Today dispatch tests this hypothesis. We proxy the subsistence wage by wage level in agriculture. Then we test the prediction that wages track that rather than productivity using a panel dataset. 5/

Across specifications, we find that the Lewisian model survives empirical interrogation. We estimate that 1 sd higher subsistence wage predicts 77% higher wages in other sectors. 6/

The effect is large enough to explain the global pattern of unequal exchange documented by the Nature paper. Link to the dispatch: /7tinyurl.com/87x8chc7

If my analysis is correct, then unequal exchange will continue each country until its entire surplus population is absorbed—ie, hidden underemployment more or less vanishes. 8/

It also has implications for the debate over fertility decline. If my analysis is correct, demographic decline could be especially helpful for poor countries trapped by the Lewisian logic. 9/

Perhaps it also explains the Indo-Chinese divergence. Their respective top and bottom-heavy strategies meant that China could escape the Lewisian trap, but India could not. This is an instance of emergent properties not reducible to micro-local structures. /10

After this exercise, I feel like I have some grasp of this pattern at the largest of scales. But I'm still in shock. Wow! /fin

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh