1/ “Democracy is a form of mass neurosis.”

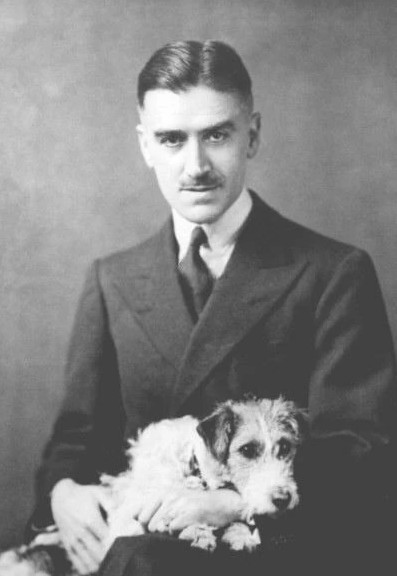

Anthony Mario Ludovici was born in London on January 8, 1882, into a society and a civilization already yielding to the democratic and egalitarian impulses that were to become the constant adversaries of his life, and the abiding bane of the West.

His name is now largely absent from public memory, yet in the first decades of the twentieth century he stood among the most cultivated and steadfast defenders of the old European order.

Author of more than fifty books, one of the first translators of Nietzsche into English, original philosopher, painter, critic, polemicist, and political writer, he combined the breadth of a Renaissance humanist with the precision of a strategist. His writings traversed politics, religion, aesthetics, anthropology, and the relations between the sexes, yet his central and immutable concern was the cultivation and preservation of the highest human types.

Anthony Mario Ludovici was born in London on January 8, 1882, into a society and a civilization already yielding to the democratic and egalitarian impulses that were to become the constant adversaries of his life, and the abiding bane of the West.

His name is now largely absent from public memory, yet in the first decades of the twentieth century he stood among the most cultivated and steadfast defenders of the old European order.

Author of more than fifty books, one of the first translators of Nietzsche into English, original philosopher, painter, critic, polemicist, and political writer, he combined the breadth of a Renaissance humanist with the precision of a strategist. His writings traversed politics, religion, aesthetics, anthropology, and the relations between the sexes, yet his central and immutable concern was the cultivation and preservation of the highest human types.

2/ Ludovici’s intellectual formation was grounded in an unshakable acceptance of hierarchy as a law of nature. He held that political order is never an abstraction, but the outward form of a ruling type, composed of men whose lineage, discipline, and intelligence have prepared them for the burden of command.

Democracy, in his estimation, was a political superstition, built upon the mystical “divine right” of majorities, an arrangement by which authority must inevitably pass into the hands of the least capable and the least far-seeing. He acknowledged the masses for their worth as workers and as soldiers, yet denied that their counsel in the affairs of state could ever be set beside the judgment of a hereditary elite, bound in duty to the destiny of the nation. In such works as “The False Assumptions of Democracy” and “A Defence of Aristocracy,” he exposed with patient severity the processes by which the modern franchise degrades governance into bribery, manipulation, and the restless pursuit of transient popularity.

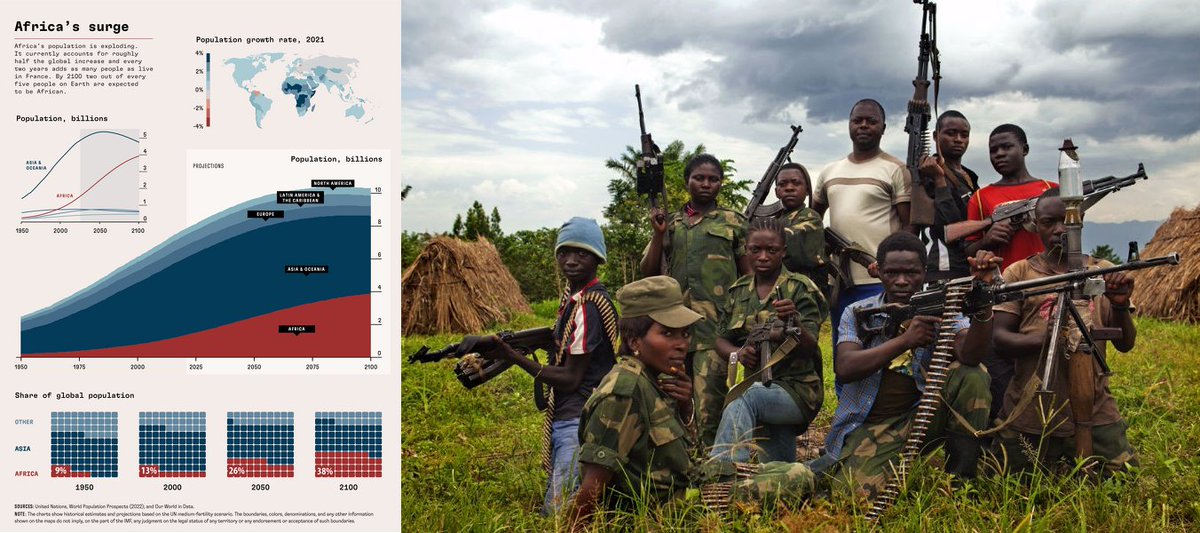

His critique reached beyond the province of political theory into the very foundations of civilization. For Ludovici, aristocracy was not a mere constitutional arrangement but a principle of selection that had operated across the centuries in every culture that rose to greatness. Those civilizations which attained the highest refinements of art, philosophy, and statecraft, including Egypt, Greece, Rome, the great cultures of Asia, and the Americas, were all distinguished by relative isolation, by endogamy among their ruling houses, and by a deliberate cultivation of their own kind.

He observed that Egyptians, Jews, Greeks, and Incas alike, at the height of their powers, had set firm barriers against foreign admixture, and that their elites, to preserve the integrity of type, often resorted to close inbreeding. In the modern world, cosmopolitanism has broken these barriers, dissolving not only the physical harmony of a people but the cultural cohesion upon which the edifice of high civilization rests.

Democracy, in his estimation, was a political superstition, built upon the mystical “divine right” of majorities, an arrangement by which authority must inevitably pass into the hands of the least capable and the least far-seeing. He acknowledged the masses for their worth as workers and as soldiers, yet denied that their counsel in the affairs of state could ever be set beside the judgment of a hereditary elite, bound in duty to the destiny of the nation. In such works as “The False Assumptions of Democracy” and “A Defence of Aristocracy,” he exposed with patient severity the processes by which the modern franchise degrades governance into bribery, manipulation, and the restless pursuit of transient popularity.

His critique reached beyond the province of political theory into the very foundations of civilization. For Ludovici, aristocracy was not a mere constitutional arrangement but a principle of selection that had operated across the centuries in every culture that rose to greatness. Those civilizations which attained the highest refinements of art, philosophy, and statecraft, including Egypt, Greece, Rome, the great cultures of Asia, and the Americas, were all distinguished by relative isolation, by endogamy among their ruling houses, and by a deliberate cultivation of their own kind.

He observed that Egyptians, Jews, Greeks, and Incas alike, at the height of their powers, had set firm barriers against foreign admixture, and that their elites, to preserve the integrity of type, often resorted to close inbreeding. In the modern world, cosmopolitanism has broken these barriers, dissolving not only the physical harmony of a people but the cultural cohesion upon which the edifice of high civilization rests.

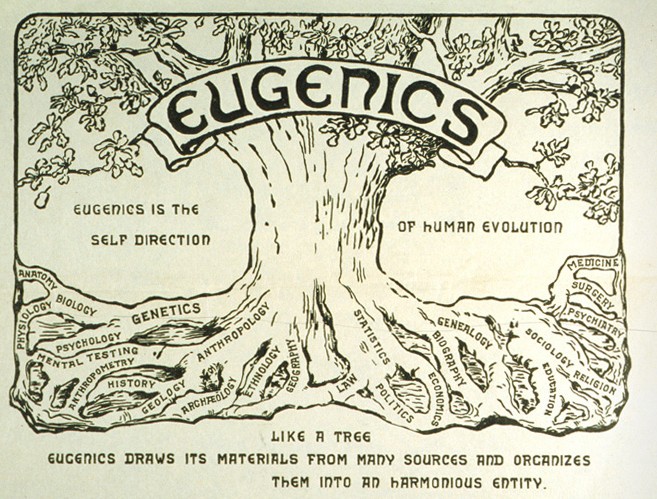

3/ This biological realism informed every dimension of his thought. In “The Choice of a Mate” and “The Quest of Human Quality,” he maintained that the blending of widely divergent stocks, even within Europe, often produced physical and psychological disharmony, much as a craftsman would never assemble a mechanism from incompatible parts. The ruling class, he held, must be both biologically sound and culturally rooted, for only within stable and homogeneous conditions can heredity accumulate the virtues required for enduring greatness.

This conviction was reinforced by his long engagement with Nietzsche, whom he regarded not merely as a philosopher of individual will but as a thinker of types, a diagnostician of the moral and physiological health of peoples. In his translations, such as “The Life of Nietzsche” and “Who is to be Master of the World?,” and in his own critical expositions, he drew out the connection between the cultivation of higher men and the ordering of society according to rank, strength, and creative vitality. For Ludovici, Nietzsche’s vision was not an abstract metaphysic but a practical programme for the regeneration of the European stock, uniting biology, culture, and moral philosophy in the service of breeding a nobler type.

His respect for the aristocratic principle did not obscure its historical failures. He reproved the European nobility for neglecting the elementary laws of breeding, for marrying without regard to character or health, for introducing sterility through alliances with wealthy but infertile heiresses, and for permitting their ranks to be diluted by fashion, vanity, and indiscipline. He judged the aristocracies of his own time to be largely hollow, peopled by inheritors without vocation, unwilling or unable to resist the encroachments of finance, the press, and mass politics.

Ludovici’s conservatism was not a matter of backward yearning for a long dead past, but the expression of a strategic mind allied to historical understanding. He recognized that a new aristocracy could arise only through deliberate selection and the acknowledgment of natural inequality. His vision of the future was founded upon the establishment of a political and cultural order led by the most intelligent, the most vigorous in health, and the most creative in spirit, with the rest of society ordered in accordance with their direction. He dismissed the sentimentalism that masked egalitarian ideals, tracing their origin to the theological leveling of the Reformation and the political upheavals of the French Revolution. In his judgment, the democratic drift moved inexorably toward socialism and, in the end, toward the dissolution of order itself.

This conviction was reinforced by his long engagement with Nietzsche, whom he regarded not merely as a philosopher of individual will but as a thinker of types, a diagnostician of the moral and physiological health of peoples. In his translations, such as “The Life of Nietzsche” and “Who is to be Master of the World?,” and in his own critical expositions, he drew out the connection between the cultivation of higher men and the ordering of society according to rank, strength, and creative vitality. For Ludovici, Nietzsche’s vision was not an abstract metaphysic but a practical programme for the regeneration of the European stock, uniting biology, culture, and moral philosophy in the service of breeding a nobler type.

His respect for the aristocratic principle did not obscure its historical failures. He reproved the European nobility for neglecting the elementary laws of breeding, for marrying without regard to character or health, for introducing sterility through alliances with wealthy but infertile heiresses, and for permitting their ranks to be diluted by fashion, vanity, and indiscipline. He judged the aristocracies of his own time to be largely hollow, peopled by inheritors without vocation, unwilling or unable to resist the encroachments of finance, the press, and mass politics.

Ludovici’s conservatism was not a matter of backward yearning for a long dead past, but the expression of a strategic mind allied to historical understanding. He recognized that a new aristocracy could arise only through deliberate selection and the acknowledgment of natural inequality. His vision of the future was founded upon the establishment of a political and cultural order led by the most intelligent, the most vigorous in health, and the most creative in spirit, with the rest of society ordered in accordance with their direction. He dismissed the sentimentalism that masked egalitarian ideals, tracing their origin to the theological leveling of the Reformation and the political upheavals of the French Revolution. In his judgment, the democratic drift moved inexorably toward socialism and, in the end, toward the dissolution of order itself.

4/ An accomplished artist and former secretary to Auguste Rodin, Ludovici discerned in high art the vitality of the ruling type. Civilizations of rank and tradition created works that affirmed life, embodied their racial ideals, and endowed their peoples with a sense of mission. Societies governed by democratic principles, fragmented into a multitude of tastes and schools, produced art without unity or purpose, abandoning the discipline of ideal form for a formless realism that mirrored their own disintegration.

On the Jewish question, Ludovici united ethnographic observation with political analysis, portraying Jews as a distinct and enduring racial type whose historic role as traders and intermediaries had endowed them with certain virtues, yet also with dispositions toward cosmopolitanism and the attenuation of local traditions. He opposed Jewish–Gentile intermarriage and regarded England’s medieval expulsion of Jews as an act of ethnic self-preservation. His judgments, however unwelcome to the prevailing liberal orthodoxy, were advanced as the considered conclusions of an anthropologist rather than the slogans of a polemicist.

Ludovici’s opposition to feminism was likewise rooted in his biological and civilizational principles. He conceived of the sexes as complementary but unequal in function, with woman’s primary vocation residing in the bearing and rearing of children. Feminist movements, the conscription of women into industrial labor, and the masculinization of female roles appeared to him as manifestations of a social disorder that enfeebled the family and, through it, the nation itself.

His life intersected with the ideological upheavals of the twentieth century. He travelled in National Socialist Germany during the 1930s and regarded with approval its measures for the improvement of national health, its elevation of labor, and its conception of art as the expression of a people’s soul. His allegiance, however, was never to a particular regime but to the abiding principles of hierarchy, selection, and cultural integrity. This independence of mind, joined to his refusal to temper his convictions, consigned him to obscurity in the decades that followed the war.

Anthony Ludovici died in 1971, leaving a body of work that stands as an unflinching indictment of the political religion of equality. In an age when the so-called conservative parties have surrendered to the dogmas of universal suffrage, individualism, and market idolatry, his thought recalls an older standard, one in which the worth of a society is measured by the quality of the men it produces to govern it.

He belongs to that rare order of Europeans who understood that the choice is never between aristocracy and democracy, but between an aristocracy shaped by conscious selection and the de facto rule of the most aggressive elements of the mass. In this light, his work endures not as a relic of the past but as a warning to the future.

On the Jewish question, Ludovici united ethnographic observation with political analysis, portraying Jews as a distinct and enduring racial type whose historic role as traders and intermediaries had endowed them with certain virtues, yet also with dispositions toward cosmopolitanism and the attenuation of local traditions. He opposed Jewish–Gentile intermarriage and regarded England’s medieval expulsion of Jews as an act of ethnic self-preservation. His judgments, however unwelcome to the prevailing liberal orthodoxy, were advanced as the considered conclusions of an anthropologist rather than the slogans of a polemicist.

Ludovici’s opposition to feminism was likewise rooted in his biological and civilizational principles. He conceived of the sexes as complementary but unequal in function, with woman’s primary vocation residing in the bearing and rearing of children. Feminist movements, the conscription of women into industrial labor, and the masculinization of female roles appeared to him as manifestations of a social disorder that enfeebled the family and, through it, the nation itself.

His life intersected with the ideological upheavals of the twentieth century. He travelled in National Socialist Germany during the 1930s and regarded with approval its measures for the improvement of national health, its elevation of labor, and its conception of art as the expression of a people’s soul. His allegiance, however, was never to a particular regime but to the abiding principles of hierarchy, selection, and cultural integrity. This independence of mind, joined to his refusal to temper his convictions, consigned him to obscurity in the decades that followed the war.

Anthony Ludovici died in 1971, leaving a body of work that stands as an unflinching indictment of the political religion of equality. In an age when the so-called conservative parties have surrendered to the dogmas of universal suffrage, individualism, and market idolatry, his thought recalls an older standard, one in which the worth of a society is measured by the quality of the men it produces to govern it.

He belongs to that rare order of Europeans who understood that the choice is never between aristocracy and democracy, but between an aristocracy shaped by conscious selection and the de facto rule of the most aggressive elements of the mass. In this light, his work endures not as a relic of the past but as a warning to the future.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh