Picture this, it's Tuesday morning in Gurgaon. Hundreds line up outside a sales office for apartments that don't exist yet. Just a 3D model. Construction starts in months, completion in 3 years. By evening, ₹500 crores in bookings collected. This is India's real estate.🧵👇

Land is the most important raw material in real estate. Developers buy outright, enter joint development agreements, or do redevelopment in cities like Mumbai, partnering with old housing societies to tear down cramped buildings and build modern complexes instead.

Each approach brings different risks and rewards, defining funding needs, project difficulty, control levels, and profitability. In greenfield projects on city outskirts, land might be 5-10% of project cost. Same building in metro city heart could be over 60% of costs.

Once you find perfect land, you need 50-60 government approvals in some cases. Building layout, environmental clearances, fire safety certificates, utility connections, each from different departments. Any delay stalls the entire project completely.

Environmental clearances alone take 3-12 months if you're lucky for projects over 20,000 sq.m. Larger projects need central government sign-off, costing even more time. But this gives you visibility into developer's future growth pipeline.

Real estate is fundamentally local. Development rules, approval processes, customer preferences, market dynamics vary dramatically place to place. Mumbai's redevelopment works differently from Bangalore's greenfield developments or Delhi's pre-defined plots.

Smart developers choose battlegrounds carefully, but single geography focus creates concentration risk. If that market sees downturn, entire business can crash. Success in one city doesn't guarantee success in another city.

Building apartment towers is expensive. Most developers get 15-25% from own money, borrow 20-35% from banks or specialized lenders. This financing mix evolves through project lifecycle, early stages often rely on private equity since banks won't lend without clearances.

Large developers with strong balance sheets have massive advantage, they can fund early stages internally without diluting equity or paying high interest rates to bridge financiers. Only later in construction phase do banks provide cheaper debt financing.

The fascinating third funding method, developers get remaining 40-60% from customers who pay in advance for apartments not yet built, called pre-sales. Customers essentially fund construction of their own homes, supplying working capital needed.

Under RERA 2016, developers must keep 70% of advance payments in special account, only usable for that project's land and construction costs. This money becomes developer's revenue only once construction milestones are achieved. Pre-sales are pipeline of future revenue.

From launch to completion, turning drawings into homes typically takes 3-4 years. Most developers don't build projects, they hire specialized contractors who bring teams, equipment, expertise. Developer is like movie producer, financing and overseeing everything.

Construction happens in phases, site preparation and foundation, erecting skeletal structure with concrete and steel, then finishing work like wiring, plumbing, flooring, painting. Unlike factory production, construction happens outdoors with hundreds of workers and multiple sub-contractors.

Weather plays huge role, monsoons, extreme heat, winter fog can slow progress. Developer attempts difficult balancing act ensuring enough money comes in through bank funding and pre-sales to get through rest of construction.

Under accounting standards, developer recognises revenue based on project completion percentage. If project is 40% complete, developer books 40% of pre-sales as revenue. Revenues measure how much of pre-sales developer can claim.

Look at collections, not just bookings. Pre-sales are promises, collections are actual cash in hand. Best developers maintain collection efficiency above 90%, nine of every ten customers pay installments on time. If this falls, it can sink strong sales projects.

Profit comes from gap between apartment selling price and building cost, plus land appreciation from developers who bought years ago. Established developers typically see 8-12% PAT margins, premium projects in supply-constrained markets hit 15-20%.

Since profit materializes in stages, developers have lumpy earnings. Low revenue quarter might not mean bad business, just delayed milestone. But big delays dent profits two ways, postponing revenue recognition and adding extra interest costs that hit margins directly.

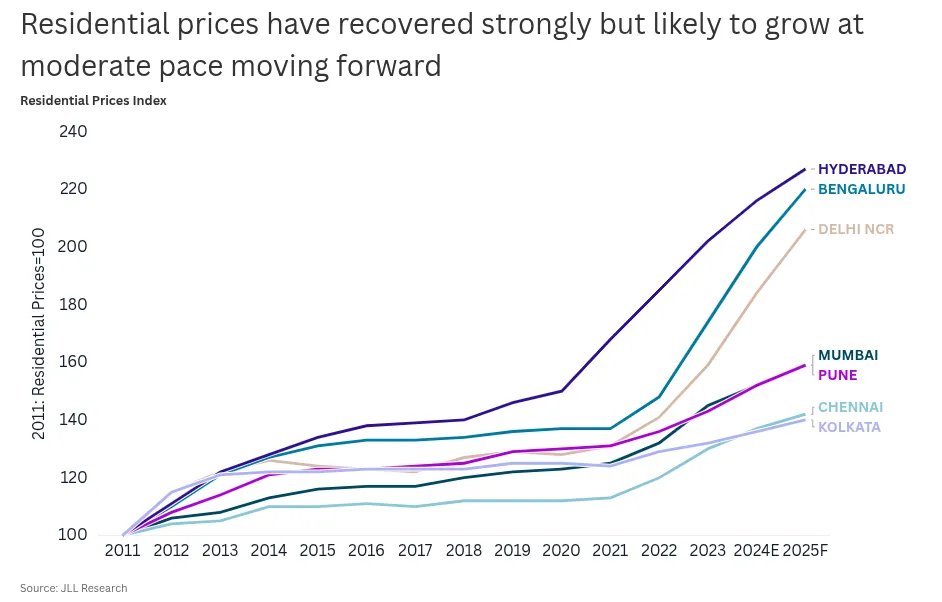

Real estate moves in predictable 7-8 year cycles with sharp rises followed by plateaus. We're in middle of upcycle that began around 2021 after nearly decade of stagnation. This time demand is overwhelmingly from end-users, not investors.

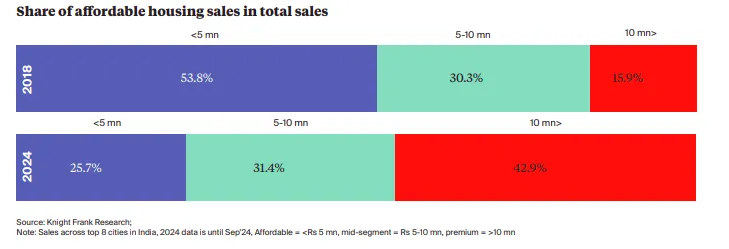

Since COVID, buyers want larger homes, that extra work-from-home room became non-negotiable. Premium and luxury segments capture increasing market share while affordable housing share shrinks. You make more selling 50 apartments at ₹2 crores than 200 at ₹50 lakhs.

In first half 2025, properties above ₹1 crore made 49% of residential sales across India's top 8 cities. In Delhi-NCR, 81% of transactions involve homes above ₹1 crore. In Bengaluru, 70% of sales were same category.

There’s another category beyond this: luxury housing, with properties between ₹20 crore and ₹50 crore. This, too, is seeing a massive surge.

There’s another category beyond this: luxury housing, with properties between ₹20 crore and ₹50 crore. This, too, is seeing a massive surge.

All of this is happening in the backdrop of rising property prices across major cities. NCR and Bengaluru lead with 14% year-on-year price increases in the first half of this year. The already unaffordable Mumbai, too, saw 8% growth.

Despite decades of consolidation attempts, real estate remains stubbornly local and fragmented. Small builder with prime land can outsell giant with mediocre land. The machine building India's skylines runs on equal parts concrete and confidence, when either runs short, whole system grinds to halt.

We cover this and one more interesting story in today's edition of The Daily Brief. Watch on YouTube, read on Substack, or listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

All links here:thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/concrete-cas…

All links here:thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/concrete-cas…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh