1/ “A decline in courage may be the most striking feature which an outside observer notices in the West in our days.”

— Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

The twentieth century drove the peoples of Europe and their kindred across the ocean to the edge of civilizational ruin. Two world wars, revolutions, and ideological convulsions shattered empires and disfigured the moral order that had sustained the West for centuries. By mid-century, an alien creed, conceived in the fevered minds of émigré revolutionaries, had seized half of Europe and cast much of the White world beneath the shadow of the gulag and the mass grave.

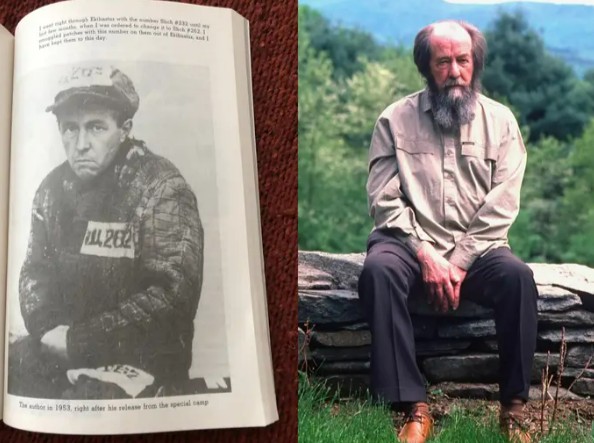

From this maelstrom emerged Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, soldier of the Red Army, inmate of the Soviet prison archipelago, and unflinching witness to the system’s crimes. His life traced the arc of his nation’s ordeal, from youthful service to disillusionment, from imprisonment to moral defiance, and finally into exile. By the 1970s, he had become the foremost voice of those who had endured the full weight of Communism, carrying that testimony into the heart of the West. In a sequence of speeches later gathered as Warning to the West, he spoke not as a partisan of Cold War maneuvering but as a moral witness to truths that transcended borders and decades.

To audiences still secure in their homelands, he spoke of dangers they could scarcely imagine. The West of his day remained composed of coherent nations, with a commanding White majority and a cultural confidence formed by centuries of civilizational achievement. Yet he perceived, even then, the same sickness that had once felled Russia taking root in the free world: a loss of will, a retreat from truth, and a readiness to appease the very forces that sought its undoing.

The empire he denounced has collapsed, yet the malady he diagnosed endures, its banner merely changed. Where class once served as the revolutionary rallying cry, race now fills that role. The objective remains the same: to dissolve the particular inheritance of the West, to estrange its peoples from their own past, and to reduce them to a formless, compliant mass.

— Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

The twentieth century drove the peoples of Europe and their kindred across the ocean to the edge of civilizational ruin. Two world wars, revolutions, and ideological convulsions shattered empires and disfigured the moral order that had sustained the West for centuries. By mid-century, an alien creed, conceived in the fevered minds of émigré revolutionaries, had seized half of Europe and cast much of the White world beneath the shadow of the gulag and the mass grave.

From this maelstrom emerged Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, soldier of the Red Army, inmate of the Soviet prison archipelago, and unflinching witness to the system’s crimes. His life traced the arc of his nation’s ordeal, from youthful service to disillusionment, from imprisonment to moral defiance, and finally into exile. By the 1970s, he had become the foremost voice of those who had endured the full weight of Communism, carrying that testimony into the heart of the West. In a sequence of speeches later gathered as Warning to the West, he spoke not as a partisan of Cold War maneuvering but as a moral witness to truths that transcended borders and decades.

To audiences still secure in their homelands, he spoke of dangers they could scarcely imagine. The West of his day remained composed of coherent nations, with a commanding White majority and a cultural confidence formed by centuries of civilizational achievement. Yet he perceived, even then, the same sickness that had once felled Russia taking root in the free world: a loss of will, a retreat from truth, and a readiness to appease the very forces that sought its undoing.

The empire he denounced has collapsed, yet the malady he diagnosed endures, its banner merely changed. Where class once served as the revolutionary rallying cry, race now fills that role. The objective remains the same: to dissolve the particular inheritance of the West, to estrange its peoples from their own past, and to reduce them to a formless, compliant mass.

2/ Among the recurring themes in Solzhenitsyn’s speeches was his contempt for those who sought to purchase peace with the currency of concession. In the 1970s, this meant Western statesmen who posed as guardians of liberty while clasping hands with the very power that sought its destruction. They signed treaties whose terms the Soviet Union ignored before the ink had dried. They dispatched aid to a regime that repaid generosity with contempt, just as earlier relief efforts during Russia’s famine years had been recast by Soviet propaganda as acts of foreign espionage. Such leaders, Solzhenitsyn observed, mistook vanity for statesmanship, polishing their prestige at home while granting material advantage to their enemies abroad.

The lesson was clear: revolutionary regimes respect only firmness and hold in contempt those who yield. This truth has not altered in the decades since. Today the enemy no longer wears the red star, yet the pattern remains. The official, mainstream Right in the West, entrusted by its supporters to resist the radicalism of the Left, instead accepts the ideological premises of its opponents. It proclaims devotion to “equality” and “diversity,” surrenders moral ground on immigration and identity, and condemns White racial consciousness while defending or celebrating every other form of ethnocentrism. It opposes border walls at home yet votes to protect the frontiers of distant states. It speaks reverently of Martin Luther King and affirms the political myths that erode its own foundation.

In doing so, it signals not magnanimity but surrender. Like the negotiators of détente, it mistakes capitulation for diplomacy. Its leaders imagine that by showing goodwill toward those who seek their ruin, they will earn restraint in return. Yet the Left offers no such reciprocity. It does not purge its most radical voices. It does not temper the stream of anti-White invective that flows from its media organs. It does not respect the limits its opponents impose on themselves. It exploits every retreat as proof of weakness and as an invitation to press further.

Solzhenitsyn recalled Lenin’s grim jest that the bourgeoisie would sell the rope for its own hanging. The observation remains apt. In our time, the rope is woven from resolutions condemning “extremism,” from legislative bargains that weaken national sovereignty, and from the moral vocabulary of our adversaries repeated faithfully by those who call themselves conservative. It is sold cheaply, in great quantity, and the buyer has not changed.

The lesson was clear: revolutionary regimes respect only firmness and hold in contempt those who yield. This truth has not altered in the decades since. Today the enemy no longer wears the red star, yet the pattern remains. The official, mainstream Right in the West, entrusted by its supporters to resist the radicalism of the Left, instead accepts the ideological premises of its opponents. It proclaims devotion to “equality” and “diversity,” surrenders moral ground on immigration and identity, and condemns White racial consciousness while defending or celebrating every other form of ethnocentrism. It opposes border walls at home yet votes to protect the frontiers of distant states. It speaks reverently of Martin Luther King and affirms the political myths that erode its own foundation.

In doing so, it signals not magnanimity but surrender. Like the negotiators of détente, it mistakes capitulation for diplomacy. Its leaders imagine that by showing goodwill toward those who seek their ruin, they will earn restraint in return. Yet the Left offers no such reciprocity. It does not purge its most radical voices. It does not temper the stream of anti-White invective that flows from its media organs. It does not respect the limits its opponents impose on themselves. It exploits every retreat as proof of weakness and as an invitation to press further.

Solzhenitsyn recalled Lenin’s grim jest that the bourgeoisie would sell the rope for its own hanging. The observation remains apt. In our time, the rope is woven from resolutions condemning “extremism,” from legislative bargains that weaken national sovereignty, and from the moral vocabulary of our adversaries repeated faithfully by those who call themselves conservative. It is sold cheaply, in great quantity, and the buyer has not changed.

3/ If appeasement was the fatal habit of Western statesmen, complacency was the vice of their peoples. Solzhenitsyn saw it in audiences who listened politely to his warnings, then returned unchanged to their routines. He likened this indifference to a blindness of the will, an incapacity to take danger seriously until it was already upon them. Peoples who imagine themselves secure will often dismiss the testimony of those who have endured what they have not, even when that testimony is offered in the hope of sparing them the same fate.

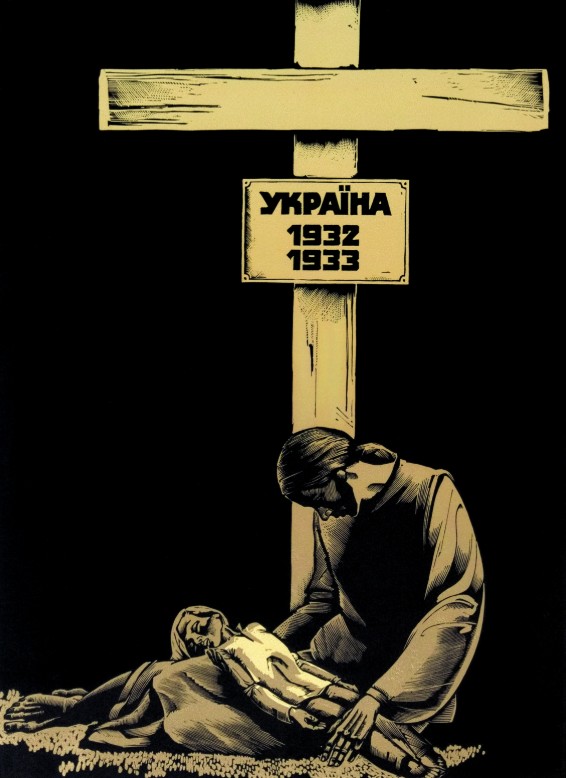

The West of the 1970s still enjoyed the fruits of its civilizational ascendancy: intact homelands, stable currencies, and a demographic composition that remained overwhelmingly White. Yet even then, Solzhenitsyn warned of an erosion of spirit, a loss of the resolve that had built and defended that world. From bitter experience, he knew that once such resolve is lost, catastrophe follows. In his own country, millions of peasants, industrious, pious, and bound by centuries of tradition, were destroyed in the name of an ideology. In Ukraine, the terror famine known as the Holodomor of 1932–33 was engineered to break a people’s will, costing millions of lives. Such events were not accidents but acts of deliberate policy, carried out with the full knowledge that the destruction of a population’s strength is the precondition for remaking it in the image of its conquerors.

The same principle operates today, though by more gradual means. White populations in the West, lulled by prosperity, are told that their dispossession is a moral duty. They are shamed for the achievements of their ancestors, urged to celebrate the settlement of their lands by alien peoples, and taught to regard their own continuity as a problem to be solved. The instruments of this policy are not famine and firing squads, but migration quotas, anti-discrimination laws, and a relentless tide of propaganda. Its consequence is the steady erosion of identity and the progressive dissolution of the capacity to resist replacement.

The Left understands the power of memory and wields it with calculation. It recites its own catalogue of suffering, embellished or invented as needed, until it hardens into an article of faith in the minds of its adherents. Whites, by contrast, have allowed their own record of suffering to be erased. They no longer recall that tens of millions of their kin perished under Communism, nor do they recognize the ideological heirs of that system when its banners are raised in Western streets. As Solzhenitsyn warned, a people that ceases to remember has already surrendered both its history and its soul. Such a people will accept degradation in any form, so long as it advances by slow degrees.

The West of the 1970s still enjoyed the fruits of its civilizational ascendancy: intact homelands, stable currencies, and a demographic composition that remained overwhelmingly White. Yet even then, Solzhenitsyn warned of an erosion of spirit, a loss of the resolve that had built and defended that world. From bitter experience, he knew that once such resolve is lost, catastrophe follows. In his own country, millions of peasants, industrious, pious, and bound by centuries of tradition, were destroyed in the name of an ideology. In Ukraine, the terror famine known as the Holodomor of 1932–33 was engineered to break a people’s will, costing millions of lives. Such events were not accidents but acts of deliberate policy, carried out with the full knowledge that the destruction of a population’s strength is the precondition for remaking it in the image of its conquerors.

The same principle operates today, though by more gradual means. White populations in the West, lulled by prosperity, are told that their dispossession is a moral duty. They are shamed for the achievements of their ancestors, urged to celebrate the settlement of their lands by alien peoples, and taught to regard their own continuity as a problem to be solved. The instruments of this policy are not famine and firing squads, but migration quotas, anti-discrimination laws, and a relentless tide of propaganda. Its consequence is the steady erosion of identity and the progressive dissolution of the capacity to resist replacement.

The Left understands the power of memory and wields it with calculation. It recites its own catalogue of suffering, embellished or invented as needed, until it hardens into an article of faith in the minds of its adherents. Whites, by contrast, have allowed their own record of suffering to be erased. They no longer recall that tens of millions of their kin perished under Communism, nor do they recognize the ideological heirs of that system when its banners are raised in Western streets. As Solzhenitsyn warned, a people that ceases to remember has already surrendered both its history and its soul. Such a people will accept degradation in any form, so long as it advances by slow degrees.

4/ Solzhenitsyn’s hatred of Communism was not limited to its politics. He saw in it a moral deformity, a will to power that treated truth, law, and human life as expendable. Its professed concern for the working class was a mask for the consolidation of authority in the hands of a narrow revolutionary elite. When workers defied that authority, they were met not with negotiation but with bullets and prison walls. In Petrograd and Novocherkassk, peaceful demonstrations were cut down by machine guns and crushed beneath tanks. In the countryside, strikes and protests were suppressed with the same brutality, and families were denied even the right to reclaim their dead.

This betrayal was no accident. Communism’s true aim was never to improve the lot of the worker, but to remake society in its entirety, regardless of the suffering inflicted. It preached liberation while imposing servitude, justifying itself through the abstraction of “economic processes” supposedly governing history. Once in power, the revolutionaries interpreted those processes in whatever manner preserved their dominance.

In his later works, Solzhenitsyn did not avoid the fact that the leadership of the early Soviet regime contained a disproportionately large number of Jews, many of them émigré intellectuals committed to the destruction of the old Russian order. Their prominence within the Bolshevik Party’s ideological and security apparatus was a matter of historical record, not polemic. For Solzhenitsyn, this was not a question of collective guilt, but of identifying the composition of the revolutionary vanguard and understanding how it shaped the nature of the regime. It was a ruling caste drawn not from the peasantry or the industrial working class, but from uprooted, alienated, and often non-Russian backgrounds, united by a doctrinal hostility toward the historic nation.

The modern Left preserves this structure but shifts its foundation. Where the Bolsheviks defined the struggle in terms of class, today’s revolutionaries define it in terms of race. The White race is cast as the permanent oppressor, to be diminished, displaced, and ultimately erased. “Racial justice” now serves as the moral banner, yet its underlying function is identical to that of early Bolshevism: the acquisition and preservation of power.

The tactic is as effective as it is dishonest. By inflaming the natural ethnocentrism of non-White populations, the Left convinces them that their future in the West is under threat, even as their material condition improves. This breeds resentment, just as class propaganda once set the poor against the middle and upper classes in Russia. The inversion is complete: the presence of Whites, their governance, and their civilizational order have historically elevated the standard of living for all within their reach, yet resentment, not gratitude, is deliberately cultivated, because resentment is the fuel that drives the machinery of revolution.

Solzhenitsyn understood that such a movement can never be placated, for its grievance is not a problem to resolve but a weapon to wield. Every compromise is taken as weakness, every concession as an invitation to demand more. To face such an enemy requires not negotiation, but the clarity to name it for what it is and the will to resist it without apology.

This betrayal was no accident. Communism’s true aim was never to improve the lot of the worker, but to remake society in its entirety, regardless of the suffering inflicted. It preached liberation while imposing servitude, justifying itself through the abstraction of “economic processes” supposedly governing history. Once in power, the revolutionaries interpreted those processes in whatever manner preserved their dominance.

In his later works, Solzhenitsyn did not avoid the fact that the leadership of the early Soviet regime contained a disproportionately large number of Jews, many of them émigré intellectuals committed to the destruction of the old Russian order. Their prominence within the Bolshevik Party’s ideological and security apparatus was a matter of historical record, not polemic. For Solzhenitsyn, this was not a question of collective guilt, but of identifying the composition of the revolutionary vanguard and understanding how it shaped the nature of the regime. It was a ruling caste drawn not from the peasantry or the industrial working class, but from uprooted, alienated, and often non-Russian backgrounds, united by a doctrinal hostility toward the historic nation.

The modern Left preserves this structure but shifts its foundation. Where the Bolsheviks defined the struggle in terms of class, today’s revolutionaries define it in terms of race. The White race is cast as the permanent oppressor, to be diminished, displaced, and ultimately erased. “Racial justice” now serves as the moral banner, yet its underlying function is identical to that of early Bolshevism: the acquisition and preservation of power.

The tactic is as effective as it is dishonest. By inflaming the natural ethnocentrism of non-White populations, the Left convinces them that their future in the West is under threat, even as their material condition improves. This breeds resentment, just as class propaganda once set the poor against the middle and upper classes in Russia. The inversion is complete: the presence of Whites, their governance, and their civilizational order have historically elevated the standard of living for all within their reach, yet resentment, not gratitude, is deliberately cultivated, because resentment is the fuel that drives the machinery of revolution.

Solzhenitsyn understood that such a movement can never be placated, for its grievance is not a problem to resolve but a weapon to wield. Every compromise is taken as weakness, every concession as an invitation to demand more. To face such an enemy requires not negotiation, but the clarity to name it for what it is and the will to resist it without apology.

5/ Solzhenitsyn never promised that resistance would be easy or that those who stood firm would live to see the reward of their defiance. From his own life, he knew that to resist is often to suffer, and that victory may not come within a single generation. Yet he also knew that the survival of a people rests on more than strategy or material strength. It rests on an unshakable moral conviction, on a belief in truths that permit neither negotiation nor compromise with falsehood.

He reminded his audiences that the dissidents of the Soviet Union possessed no armies, no wealth, and no organization worthy of the name. Their weapons were conviction, memory, and the readiness to endure persecution without yielding the ground of principle. By this firmness of spirit they endured decades of oppression. Solzhenitsyn urged the West to show the same spirit while there was still time to act without paying the full price of defeat.

In our century, the West faces a struggle no less existential. The danger is not the tank divisions of a foreign power, but the slow transformation of our nations from within. The demographic foundations of White societies are being eroded by design. The moral authority of their traditions is under constant attack. The historical memory that once bound their people together is being dismantled and replaced with a narrative of guilt and self-abnegation. The instruments differ from those used by the Soviet regime, yet the intended outcome is the same: the weakening of a people until it no longer possesses the will to shape its own destiny.

To meet such a threat, Solzhenitsyn’s standard remains: absolute moral clarity, the rejection of falsehood, and the courage to defend what is ours because it is ours. He warned that a decline in courage is the most conspicuous symptom of civilizational decay. Courage must be renewed not only in politics but in every sphere of life, in culture, in scholarship, in the formation of families, and in the open affirmation of racial and civilizational identity.

Greatness is not a summons to sentiment or to the recovery of ease. It is a summons to reclaim the will that built the West, the will to face enemies without illusion, to endure hardship without despair, and to secure a future in which our descendants may live as a free and distinct people. To shrink from this task is to confirm the grim truth Solzhenitsyn most feared: that a people who lose the will to defend their freedom will not long remain free.

He reminded his audiences that the dissidents of the Soviet Union possessed no armies, no wealth, and no organization worthy of the name. Their weapons were conviction, memory, and the readiness to endure persecution without yielding the ground of principle. By this firmness of spirit they endured decades of oppression. Solzhenitsyn urged the West to show the same spirit while there was still time to act without paying the full price of defeat.

In our century, the West faces a struggle no less existential. The danger is not the tank divisions of a foreign power, but the slow transformation of our nations from within. The demographic foundations of White societies are being eroded by design. The moral authority of their traditions is under constant attack. The historical memory that once bound their people together is being dismantled and replaced with a narrative of guilt and self-abnegation. The instruments differ from those used by the Soviet regime, yet the intended outcome is the same: the weakening of a people until it no longer possesses the will to shape its own destiny.

To meet such a threat, Solzhenitsyn’s standard remains: absolute moral clarity, the rejection of falsehood, and the courage to defend what is ours because it is ours. He warned that a decline in courage is the most conspicuous symptom of civilizational decay. Courage must be renewed not only in politics but in every sphere of life, in culture, in scholarship, in the formation of families, and in the open affirmation of racial and civilizational identity.

Greatness is not a summons to sentiment or to the recovery of ease. It is a summons to reclaim the will that built the West, the will to face enemies without illusion, to endure hardship without despair, and to secure a future in which our descendants may live as a free and distinct people. To shrink from this task is to confirm the grim truth Solzhenitsyn most feared: that a people who lose the will to defend their freedom will not long remain free.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh