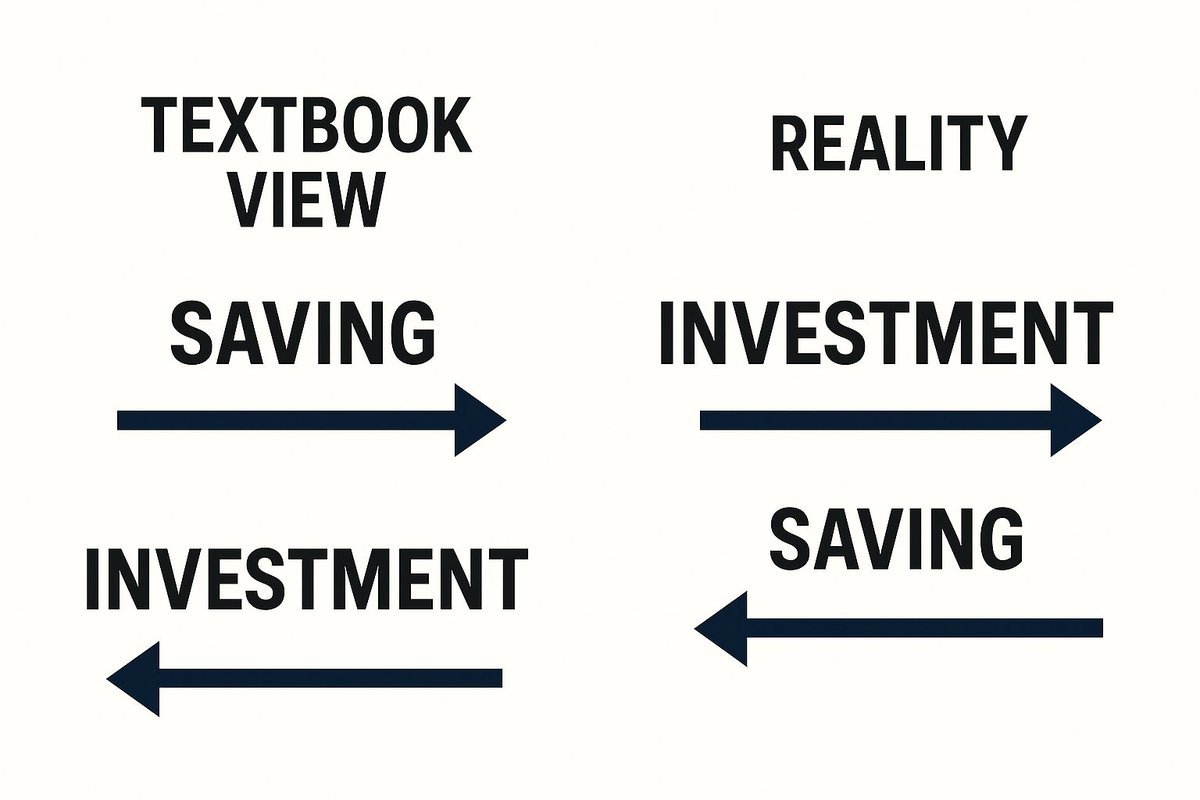

Mainstream econ says:

Households save → banks lend savings → firms invest.

Robinson flipped it: investment comes first, savings follow.

Once you see how money & banking work, it’s hard to unsee.

🧵1/10

Households save → banks lend savings → firms invest.

Robinson flipped it: investment comes first, savings follow.

Once you see how money & banking work, it’s hard to unsee.

🧵1/10

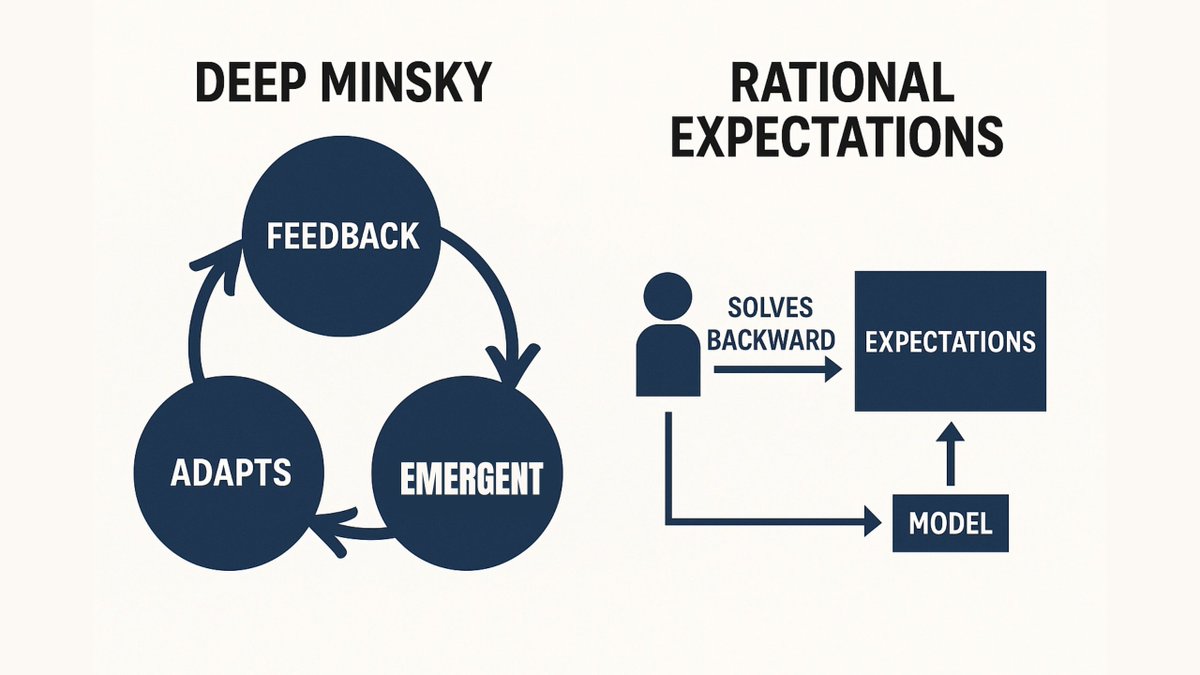

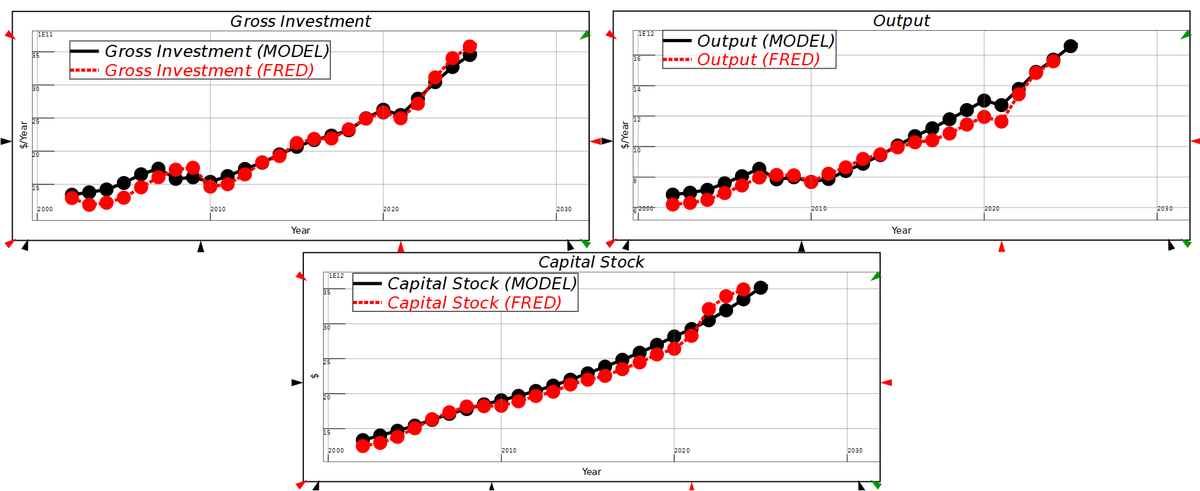

The Goodwin growth cycle shows it:

Investment drives output & jobs → higher employment boosts wages → rising wages can squeeze profits → investment slows → cycle repeats.

It starts with investment decisions, not household savings.

🧵2/10

Investment drives output & jobs → higher employment boosts wages → rising wages can squeeze profits → investment slows → cycle repeats.

It starts with investment decisions, not household savings.

🧵2/10

So where does the money for investment come from?

Not from a “pool” of prior savings.

Modern banks create credit.

When they lend, they create deposits, new money instantly funding investment.

🧵3/10

Not from a “pool” of prior savings.

Modern banks create credit.

When they lend, they create deposits, new money instantly funding investment.

🧵3/10

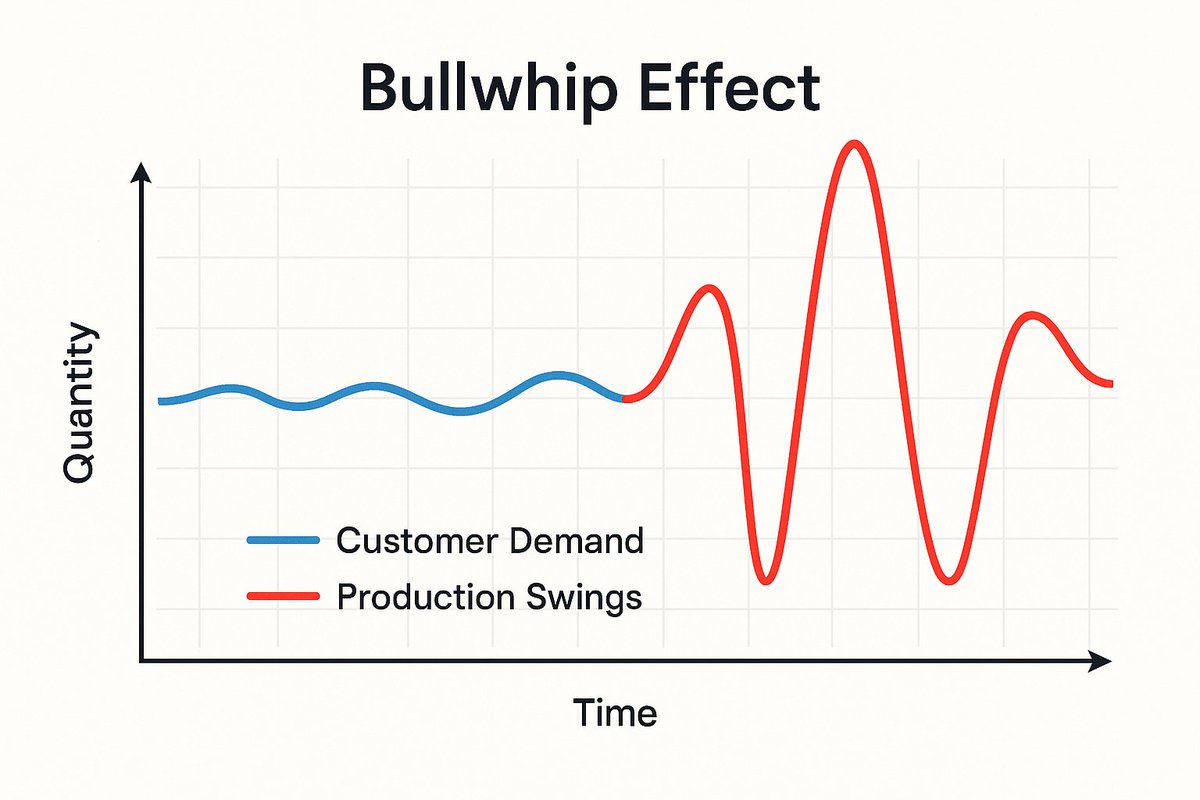

Firms borrow → spend → raise output & incomes.

Only after incomes rise does saving appear in the data.

In national accounts, investment = saving — but causality runs from investment to saving, not the other way.

🧵4/10

Only after incomes rise does saving appear in the data.

In national accounts, investment = saving — but causality runs from investment to saving, not the other way.

🧵4/10

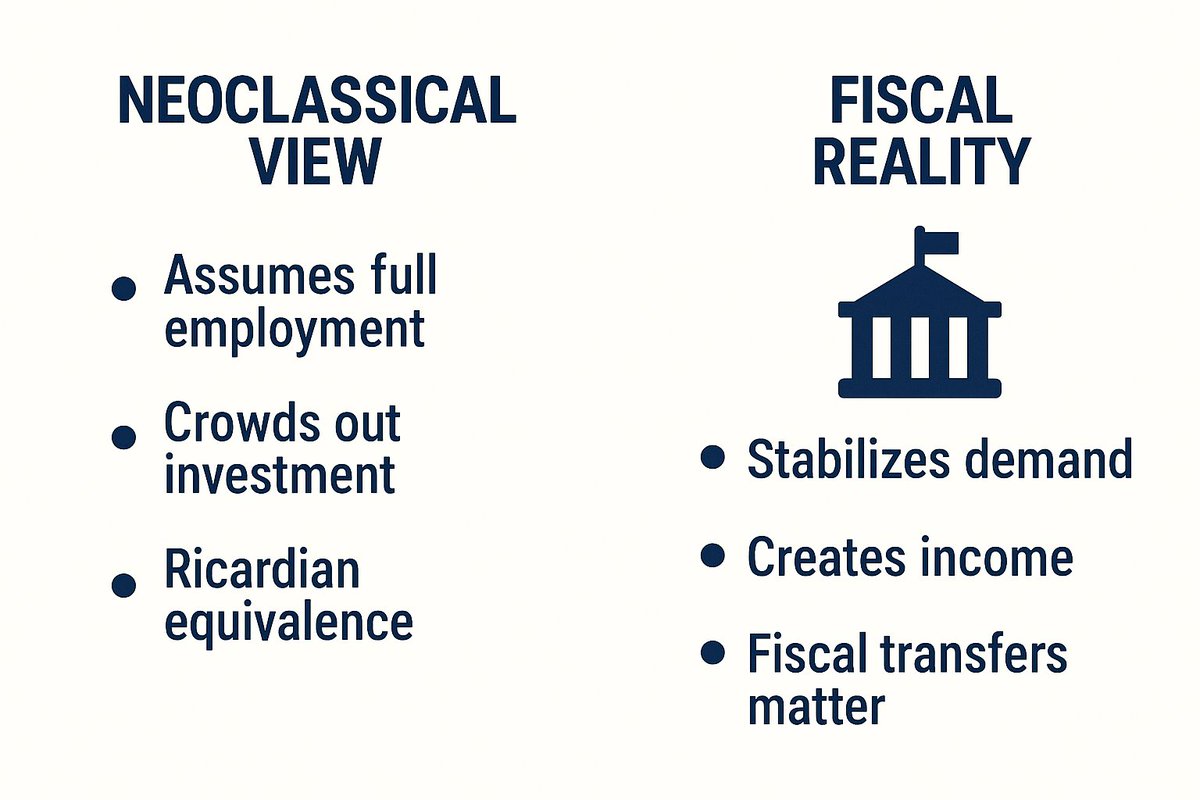

If households save more by spending less, firms sell less.

Lower sales → lower profits → less investment.

Without another source of demand (govt deficits, exports), higher saving today can actually reduce investment.

🧵5/10

Lower sales → lower profits → less investment.

Without another source of demand (govt deficits, exports), higher saving today can actually reduce investment.

🧵5/10

Keen’s extensions to Goodwin add private debt:

Firms invest if profitable demand is there.

If profits aren’t enough, they borrow, banks create the credit they need.

Again: credit & investment lead; savings follow.

🧵6/10

Firms invest if profitable demand is there.

If profits aren’t enough, they borrow, banks create the credit they need.

Again: credit & investment lead; savings follow.

🧵6/10

Policy flip:

If you want more investment, don’t push for more saving first.

Give firms reasons to invest & ensure credit supply.

The saving will happen automatically as a byproduct of higher incomes.

🧵7/10

If you want more investment, don’t push for more saving first.

Give firms reasons to invest & ensure credit supply.

The saving will happen automatically as a byproduct of higher incomes.

🧵7/10

If households cut spending & no one else fills the gap, the cycle reverses:

Investment slows → incomes stagnate → savings vanish.

High saving without offsetting demand is self-defeating.

🧵8/10

Investment slows → incomes stagnate → savings vanish.

High saving without offsetting demand is self-defeating.

🧵8/10

In a credit-creating economy, investment is the engine.

Savings are just the shadow it casts.

Robinson’s line isn’t just rhetoric, it’s a basic truth about how monetary economies work.

🧵9/10

Savings are just the shadow it casts.

Robinson’s line isn’t just rhetoric, it’s a basic truth about how monetary economies work.

🧵9/10

We should stop designing policy as if savings are the fuel for growth.

Investment decisions, backed by a banking system that can create credit, come first.

📖 Full blog here →

🧵10/10

patreon.com/posts/investme…

Investment decisions, backed by a banking system that can create credit, come first.

📖 Full blog here →

🧵10/10

patreon.com/posts/investme…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh