Did you know the American $1 bill references Virgil?

The Great Seal featured on the bill was designed by a Latin teacher, and he left a reference to the Aeneid on the design.

But there’s more — America’s entire ethos has Roman underpinnings…🧵

The Great Seal featured on the bill was designed by a Latin teacher, and he left a reference to the Aeneid on the design.

But there’s more — America’s entire ethos has Roman underpinnings…🧵

To understand how America adopted a Roman mentality, we first need to explore the idea of “Roman exceptionalism.”

It was essentially a type of self-confidence — a belief that Rome’s culture was better than all others.

It was essentially a type of self-confidence — a belief that Rome’s culture was better than all others.

This mindset is hinted at in the Aeneid, where the god Jupiter proclaims:

“I have granted [the Romans] empire without end.”

Virgil’s work proudly boasts how Rome believed it was destined to rule the world — that it was *exceptional*.

“I have granted [the Romans] empire without end.”

Virgil’s work proudly boasts how Rome believed it was destined to rule the world — that it was *exceptional*.

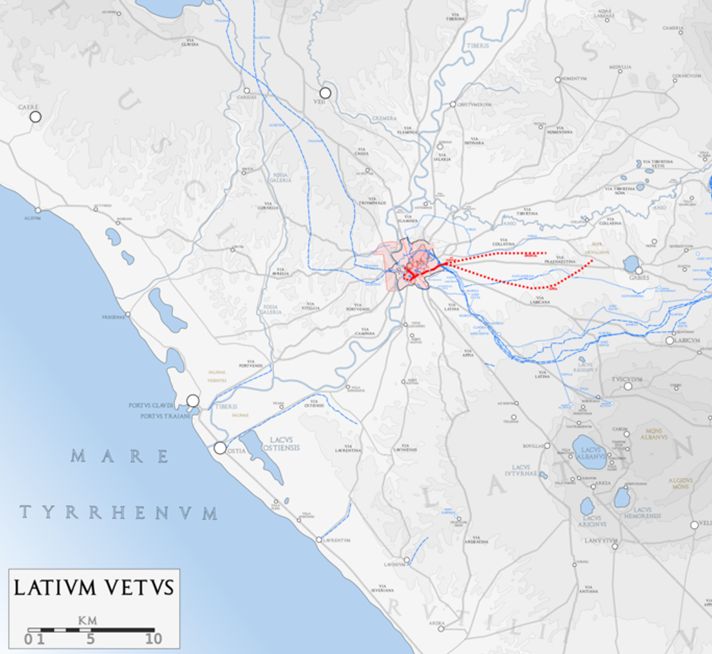

Written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, the Aeneid has since been deemed Rome’s “national epic” — a piece of literature of grand scope which captures the spirit of a people.

Though written during a period of immense disorder, it embraced a belief in the greatness of Rome…

Though written during a period of immense disorder, it embraced a belief in the greatness of Rome…

After years of civil war, Augustus Caesar envisioned a new era of peace and prosperity, one that was reminiscent of the Old Republic. Augustus hoped that by returning to traditional Roman values, Romans would move past the turmoil of the previous decades.

The Aeneid reflected this aim as it depicted the hero Aeneas — a battle-weary refugee of the destroyed city of Troy — who was loyal to his destiny and his nation above personal ambition.

Aeneas thus represented the ideal Roman.

Aeneas thus represented the ideal Roman.

Though Augustus likely commissioned the work to legitimize his own rule by tying his family back to Trojan times, the Aeneid also gave the Roman people a heroic founding myth that proved Fate had given them rule of the entire world…

Jupiter says of Aeneas:

“He was to be ruler of Italy,

Potential empire, armorer of war…

And bring the whole world under law's dominion.”

Aeneas was destined to found an empire that would subjugate every known land.

“He was to be ruler of Italy,

Potential empire, armorer of war…

And bring the whole world under law's dominion.”

Aeneas was destined to found an empire that would subjugate every known land.

This founding myth gave the Roman people legitimacy, and a casus belli to conquer all known lands — if the gods and Fate itself were in their corner, who could be against them?

Not only did the Romans of Augustus' time think they had good cause to conquer their enemies, but believed that by ruling them, they would bring about a “golden age”…

Anchises, Aeneas’ father, tells his son that “ruling the nations with power” will be his skill; later, he envisions an Age of Gold under Augustus:

“Caesar Augustus, son of the deified,

Who shall bring once again an Age of Gold.”

“Caesar Augustus, son of the deified,

Who shall bring once again an Age of Gold.”

But it was not merely myth that gave Romans this assuredness of their position as masters of the known world.

History — or at least the Roman version of history — proved their case.

History — or at least the Roman version of history — proved their case.

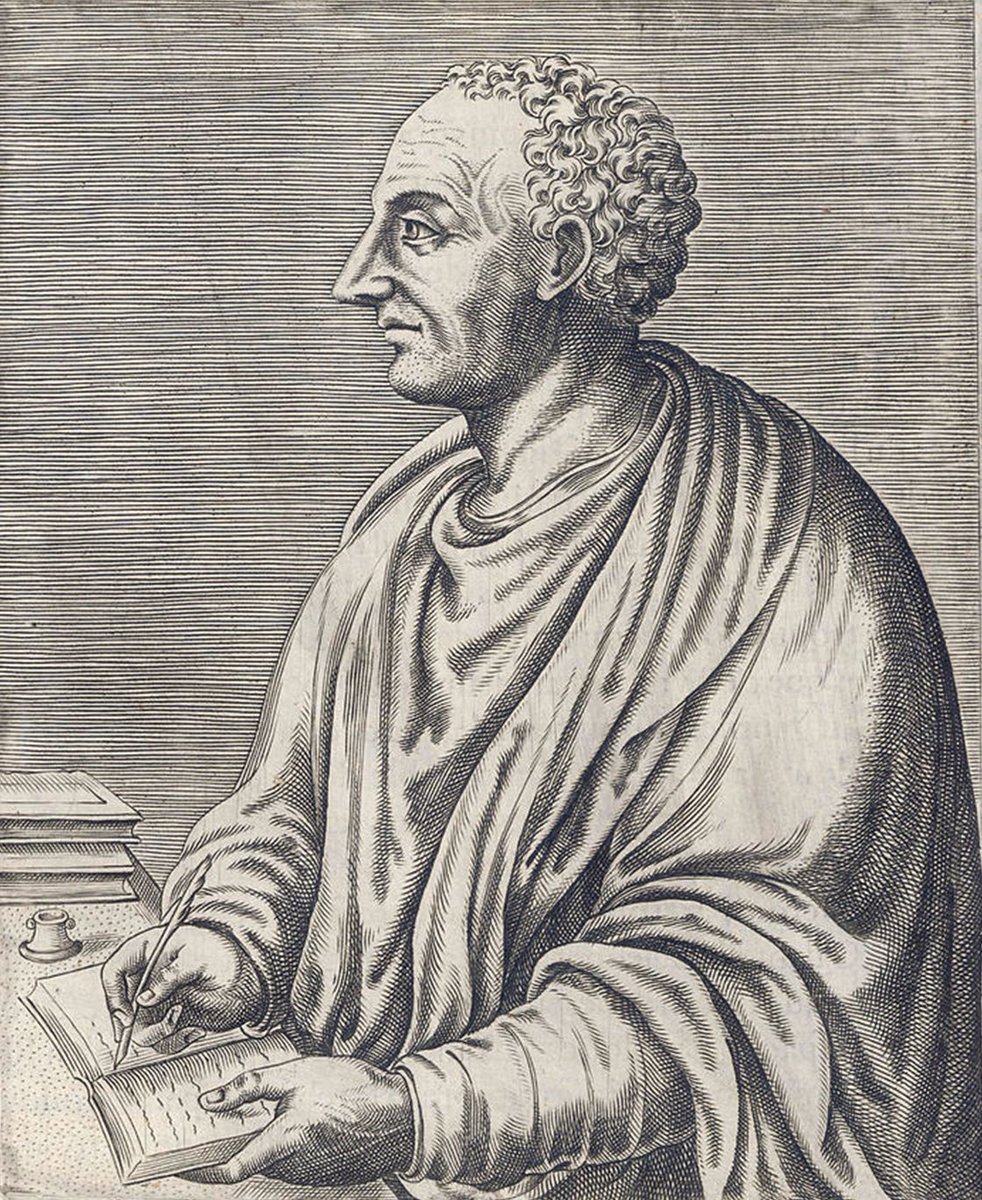

The historian Livy portrayed Rome as a liberator, where its wars were fought to free peoples from unjust rule. One could see how this was a justification for Rome’s domination — “We’re on the side of the little guys! They *want* to join our empire!”

Livy writes:

“There was one nation in the world which would fight for the liberties of others at its own cost, with its own labor, and at its own danger. It was even ready to cross the sea to make sure there was no unjust rule anywhere and that everywhere justice, right, and law would prevail.”

“There was one nation in the world which would fight for the liberties of others at its own cost, with its own labor, and at its own danger. It was even ready to cross the sea to make sure there was no unjust rule anywhere and that everywhere justice, right, and law would prevail.”

Cicero held the same sentiment:

“Our people, through repeatedly defending their allies, have ended up as master of the world.”

These statements hint that Rome maintained the perception of a virtuous people who only fought righteous wars. Rome fought for “just and pious” reasons

“Our people, through repeatedly defending their allies, have ended up as master of the world.”

These statements hint that Rome maintained the perception of a virtuous people who only fought righteous wars. Rome fought for “just and pious” reasons

Rome’s many conquests were therefore perceived as wars of liberty which freed oppressed people from despotic regimes and inferior cultures.

Basically, Romans saw themselves as the “good guys.”

Sound familiar?

Basically, Romans saw themselves as the “good guys.”

Sound familiar?

This belief also hinted at a sense of superiority, that Rome’s culture was intrinsically better than others’, and Romans had a moral duty to spread their influence as far as possible.

Looking at the success of Greco-Roman civilization compared with their contemporaries, it's hard to blame them for their smugness.

Rome’s technological, military, and cultural dominance was proof of its greatness.

Rome’s technological, military, and cultural dominance was proof of its greatness.

But Rome was far from the only culture to view itself as exceptional.

Nearly 2000 years later, another nation birthed from “refugees” and outcasts like Aeneas fleeing persecution embodied the same self-confidence…

Nearly 2000 years later, another nation birthed from “refugees” and outcasts like Aeneas fleeing persecution embodied the same self-confidence…

America, forged from adventurers, exiles, and the religiously persecuted, viewed its founding myth and subsequent expansion along the same lines as Rome.

Just like Aeneas established Italy as the base of an empire, Americans sensed their newfound nation was destined to expand.

Just like Aeneas established Italy as the base of an empire, Americans sensed their newfound nation was destined to expand.

America’s geographical position naturally lent itself to Westward expansion — the original colonies occupied the far-east side of a massive continent only sparsely populated by disunified native tribes.

And like Rome, God was on their side.

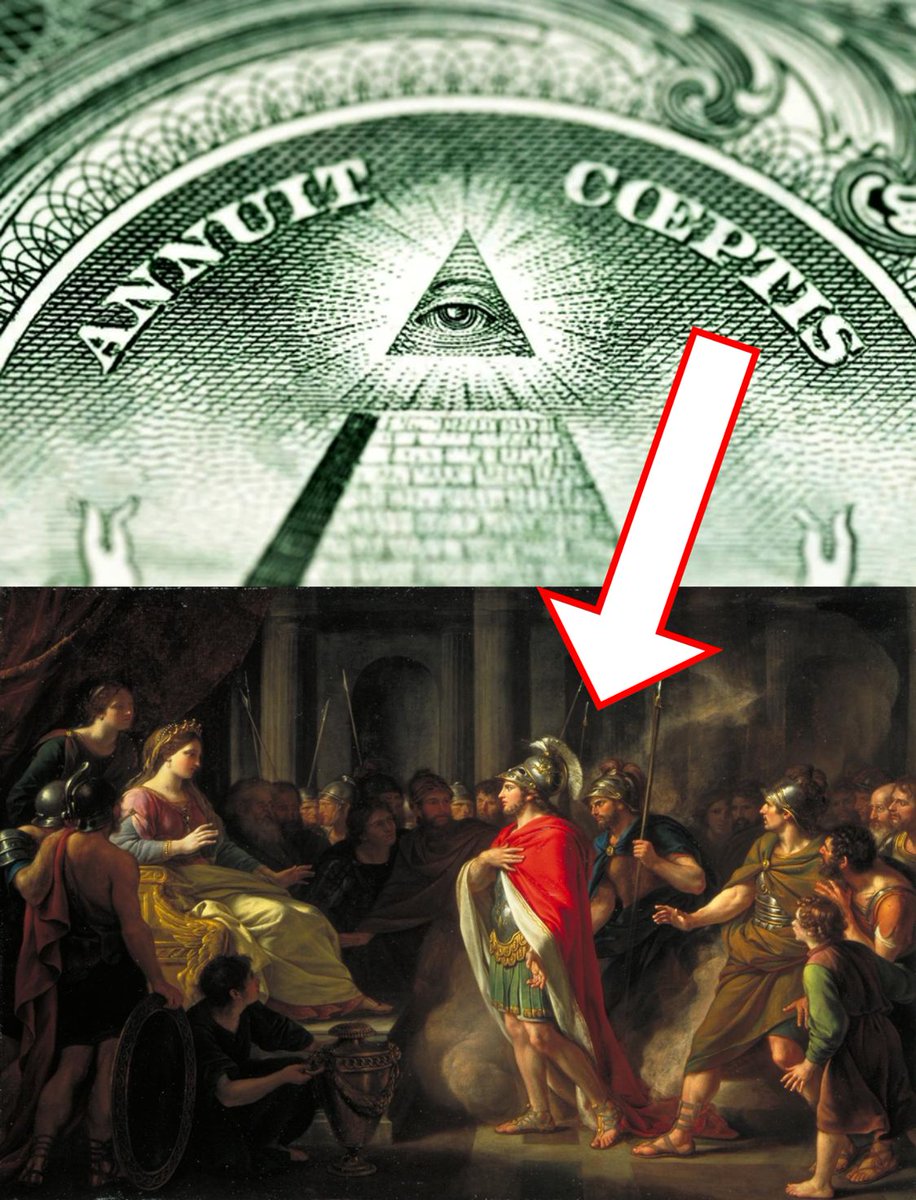

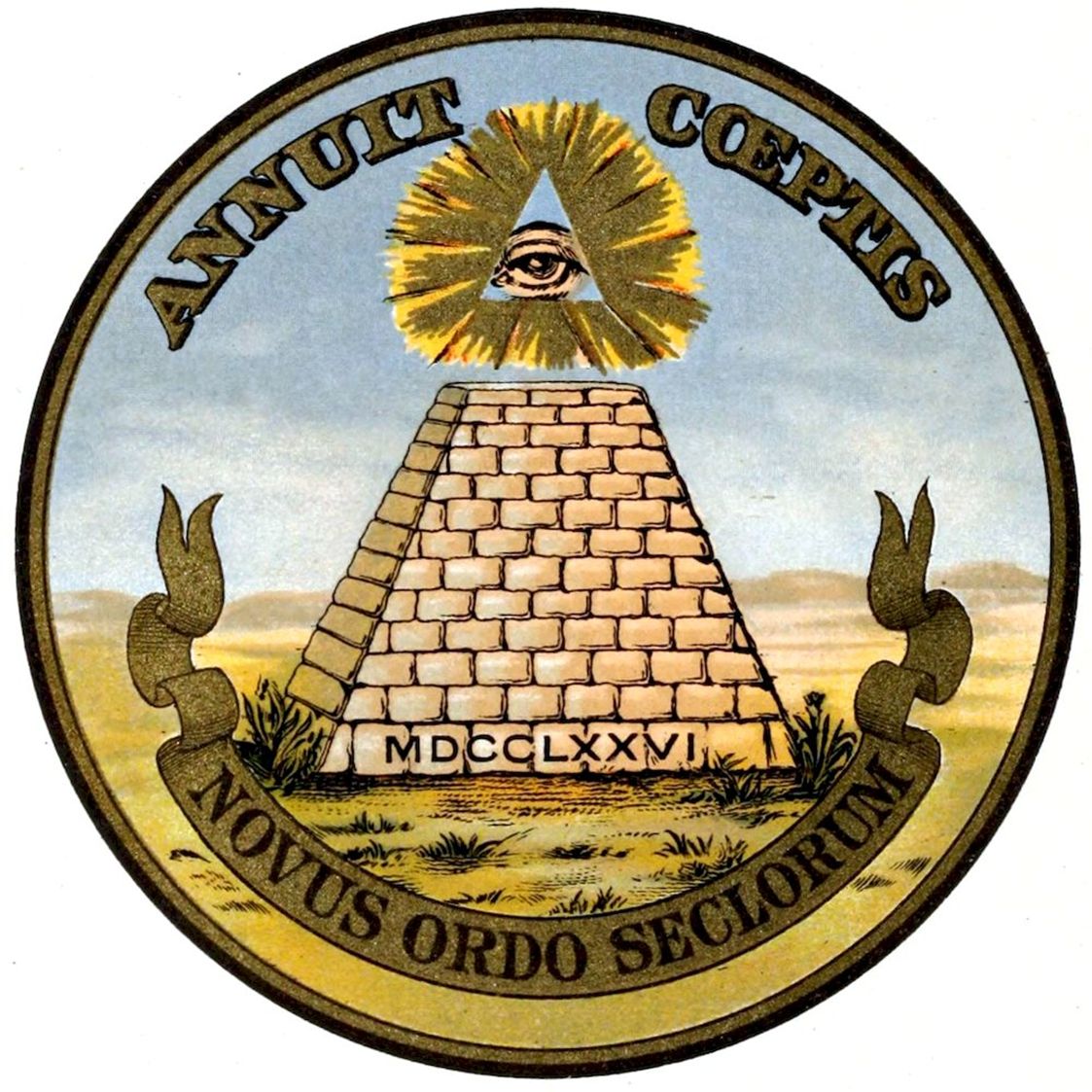

On the Great seal of the United States, an eye watches over a pyramid with the motto “Annuit Cœptis” inscribed.

On the Great seal of the United States, an eye watches over a pyramid with the motto “Annuit Cœptis” inscribed.

According to the designer Charles Tomson, a Latin teacher at the Philadelphia Academy:

“The Eye over the pyramid and the motto Annuit Cœptis allude to the many signal interpositions of providence in favor of the American cause.”

“The Eye over the pyramid and the motto Annuit Cœptis allude to the many signal interpositions of providence in favor of the American cause.”

More specifically, the term “annuit cœptis” means “He [God] has favored our endeavors,” and no doubt was influenced by a battle scene in the Aeneid:

In the scene, the future king Ascanius requests Jupiter’s aid in defeating the native Italians in order to found the Italian nation, pleading “Favor my endeavors, Jupiter.”

In the scene, the future king Ascanius requests Jupiter’s aid in defeating the native Italians in order to found the Italian nation, pleading “Favor my endeavors, Jupiter.”

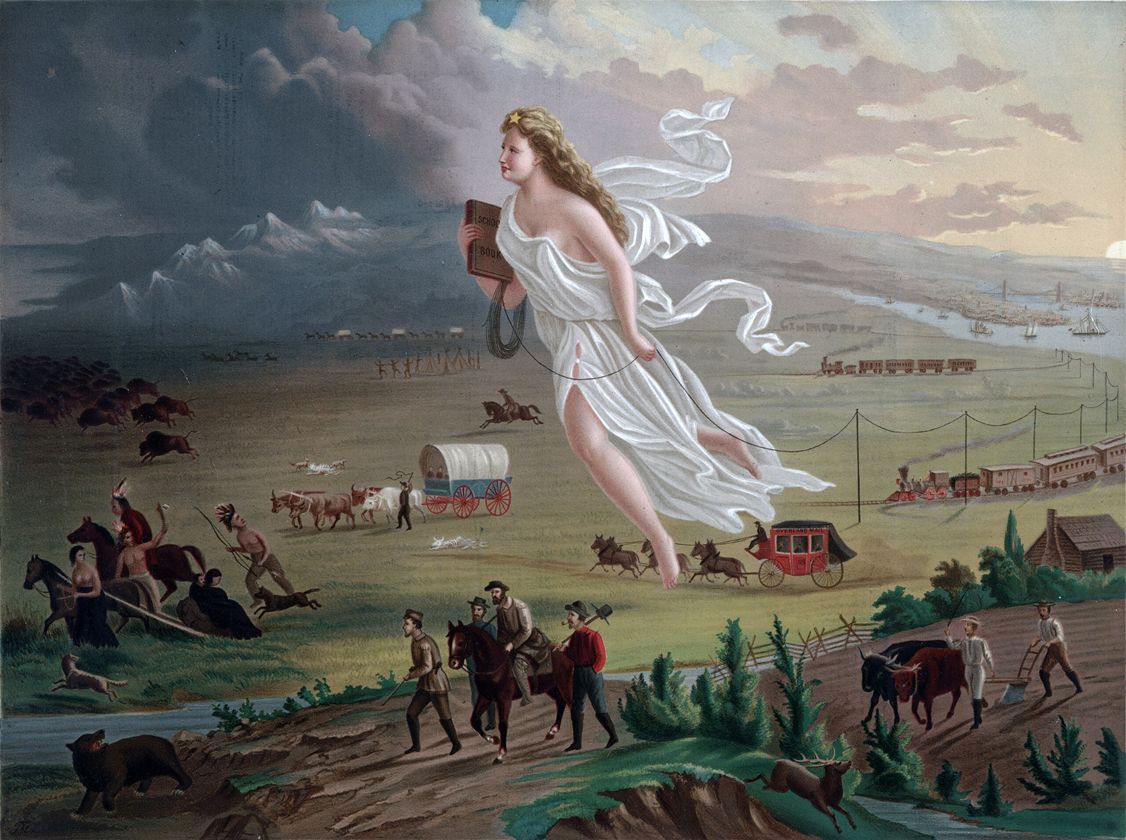

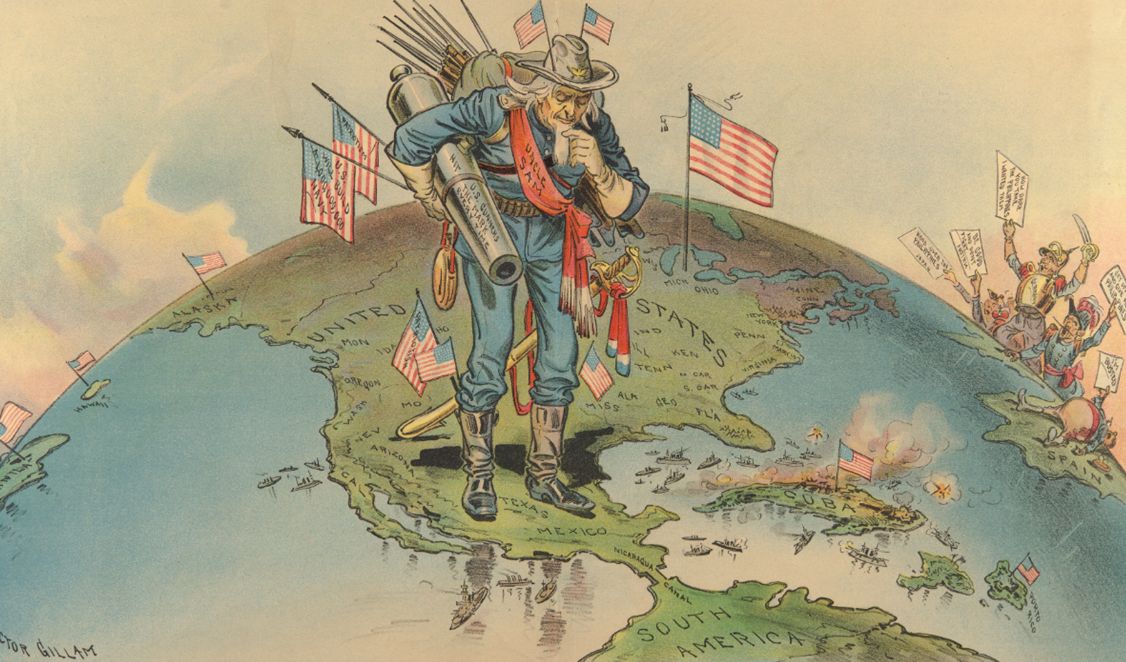

In the 19th century a new term emerged to describe the American cause: Manifest Destiny

It inspired settlers—and soldiers—to bring the “light of civilization” to the ends of the earth…

It inspired settlers—and soldiers—to bring the “light of civilization” to the ends of the earth…

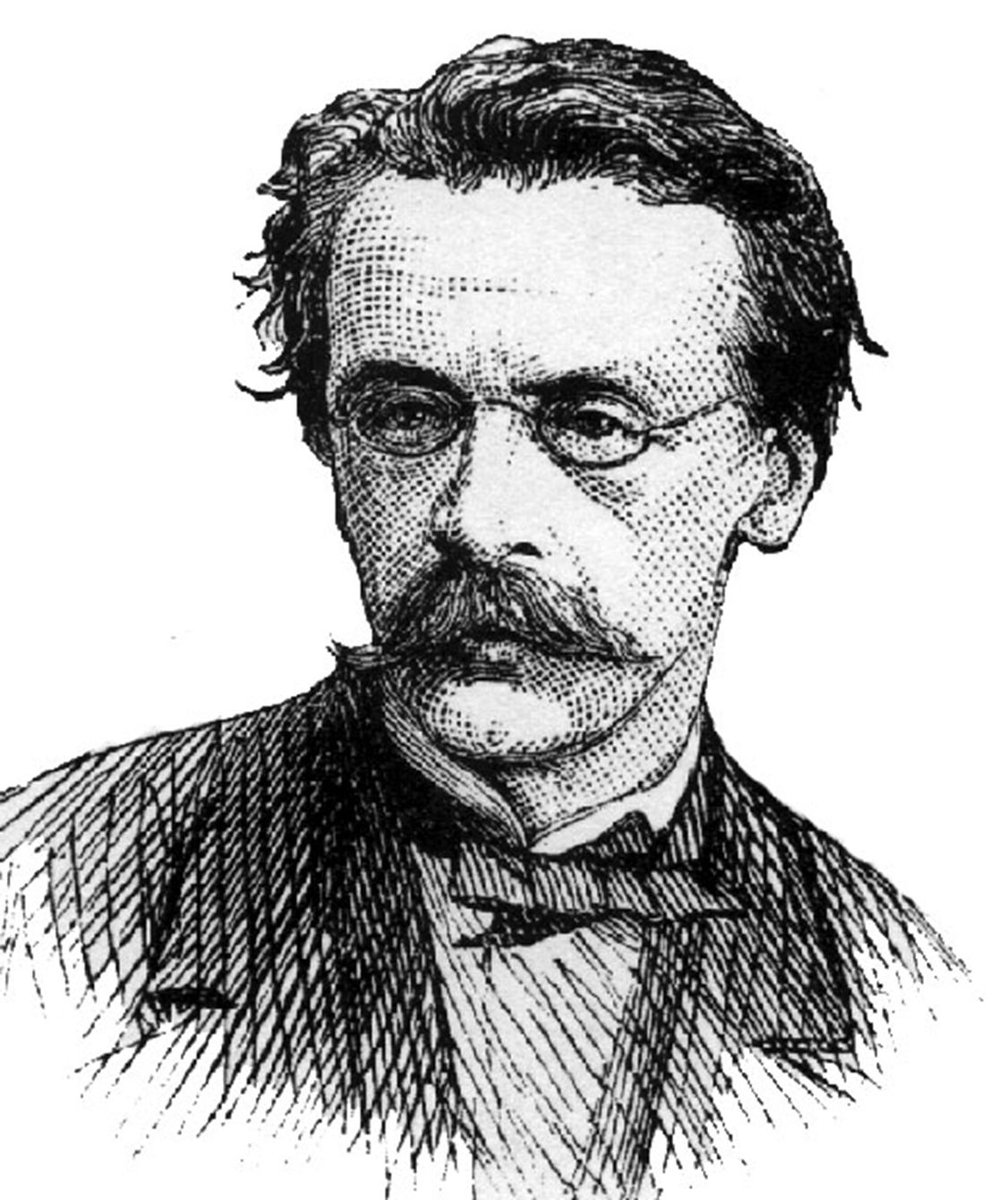

First appearing in an article by newspaper editor John O'Sullivan in 1845, the phrase was used to support the U.S.’s case in an ongoing Oregon boundary dispute with Great Britain.

In a way that echoes the Aeneid, he wrote it was America’s destiny to control North America:

“And that claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us..."

“And that claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us..."

There were 3 main assumptions behind manifest destiny:

-the unique moral virtue of the US

-the world would benefit by the spread of republicanism and the "American way of life"

-America was guaranteed to succeed in its mission

Sounds like Roman exceptionalism , right?

-the unique moral virtue of the US

-the world would benefit by the spread of republicanism and the "American way of life"

-America was guaranteed to succeed in its mission

Sounds like Roman exceptionalism , right?

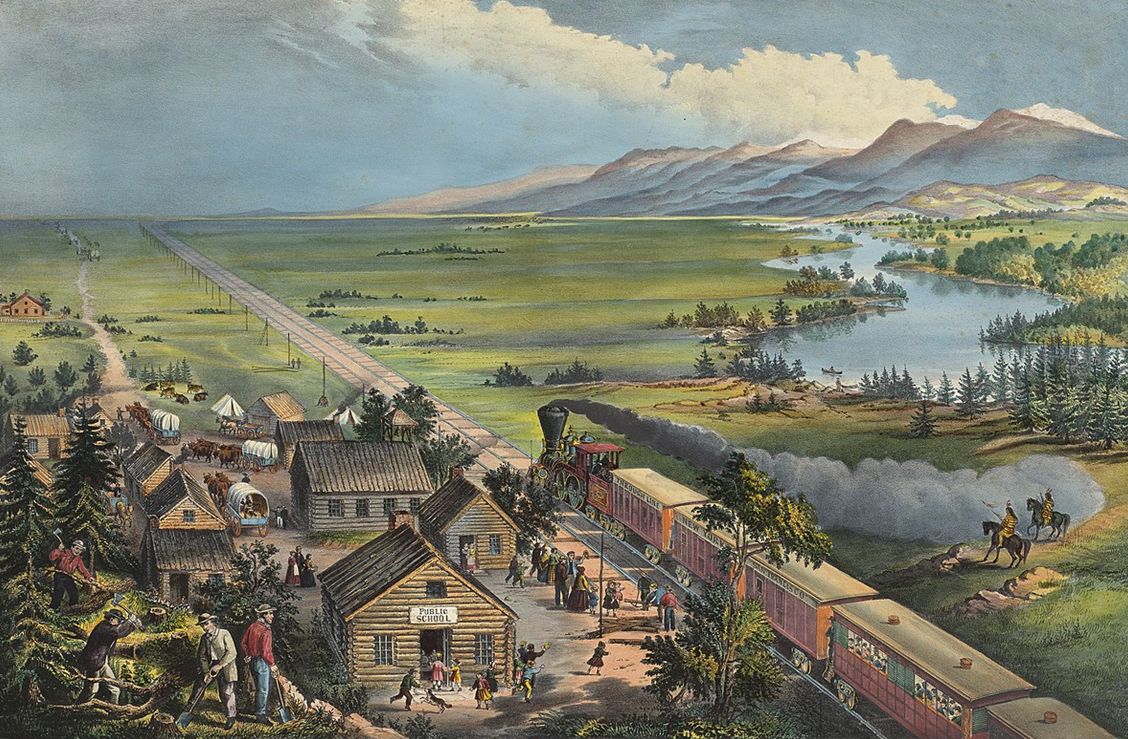

But unlike Rome’s concept of exceptionalism, manifest destiny was not necessarily a call for expansion by force — the US could grow without direct military intervention.

As Americans immigrated to new regions, they would set up democracies and gradually be added to the fold.

As Americans immigrated to new regions, they would set up democracies and gradually be added to the fold.

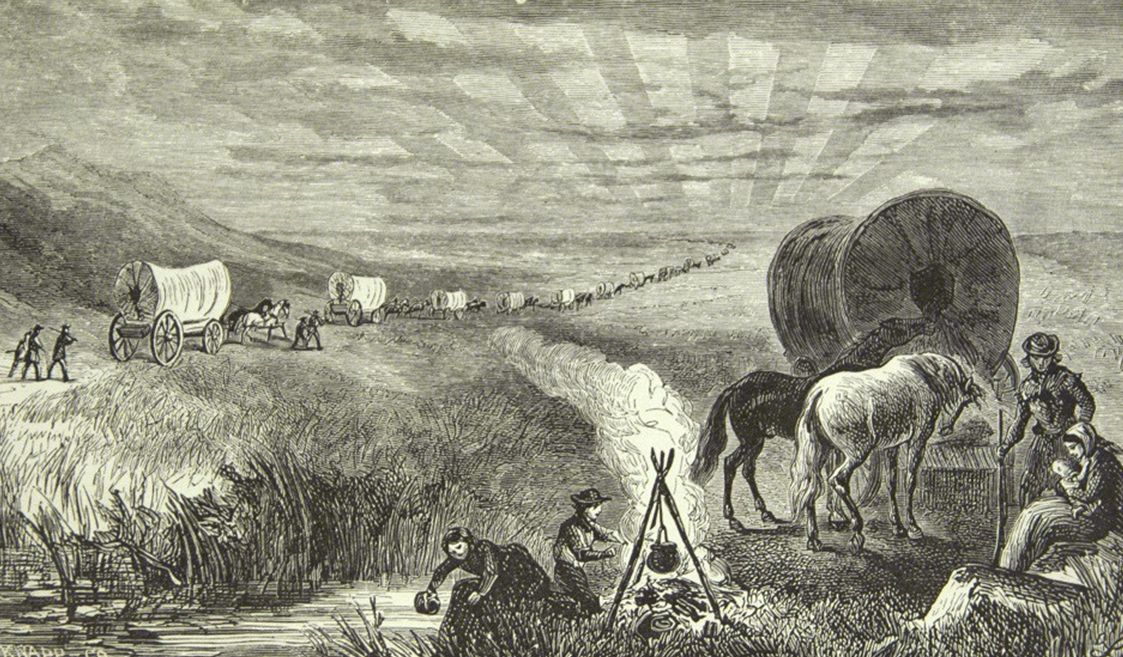

Starting with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, America's expansion westward was non-stop.

The idea of the rugged settler pushing through wilderness or “Indian country” to forge a homestead was thoroughly ingrained into the psyche of the nation.

The idea of the rugged settler pushing through wilderness or “Indian country” to forge a homestead was thoroughly ingrained into the psyche of the nation.

And it was settlers doing exactly that who ensured manifest destiny was more than an idea, but a reality.

Continental expansion eventually devoured the entire Western half of the continent, from Montana to California.

Continental expansion eventually devoured the entire Western half of the continent, from Montana to California.

The only other civilizations’ expansion that can be compared to America’s in terms of sheer cultural and technological ingenuity and lasting influence was Rome’s.

Rome transformed the Mediterranean world and laid a foundation for all civilizations after it.

Rome transformed the Mediterranean world and laid a foundation for all civilizations after it.

Their shared ethos — the belief that they were exceptional — is what propelled them to glory.

And this confidence is an important facet of all great civilizations. They believe in themselves and that their way of life is worth spreading to other cultures.

This begs the question: Do we still believe in our culture today? Sometimes the only thing separating a civilization from decline or revitalization is self-confidence.

And this confidence is an important facet of all great civilizations. They believe in themselves and that their way of life is worth spreading to other cultures.

This begs the question: Do we still believe in our culture today? Sometimes the only thing separating a civilization from decline or revitalization is self-confidence.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh