In the ancient world, the cosmos was understood through myth and stories.

Zeus ruled the heavens, Poseidon commanded the seas, and the harvest relied on the favour of Demeter.

But 2,500 years ago, on the shores of ancient Greece, a radical transformation in thought began… 🧵

Zeus ruled the heavens, Poseidon commanded the seas, and the harvest relied on the favour of Demeter.

But 2,500 years ago, on the shores of ancient Greece, a radical transformation in thought began… 🧵

Rather than just accept that gods were responsible for shaping the natural world, there were some ancient Greek thinkers who began to ask questions like:

What is the world made of?

How does it work?

Why do things change?

What is the world made of?

How does it work?

Why do things change?

They began to search for an underlying fundamental principle that could be discovered, not through the stories told by sages and travelling bards, but through reason, observation, and logic.

They called this principle the arche.

They called this principle the arche.

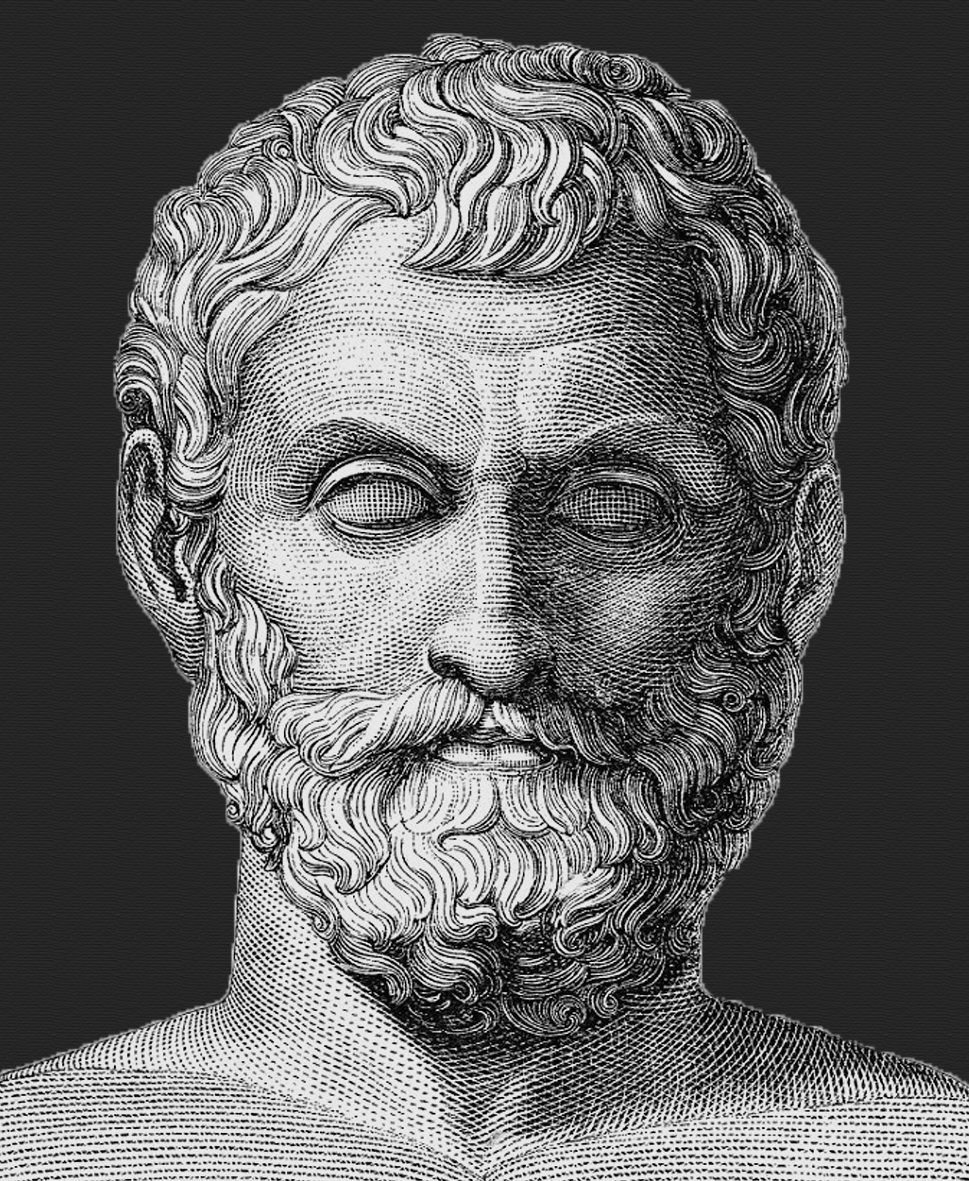

The first of these thinkers was Thales of Miletus.

He thought that water was the arche of all things.

His reasoning being that life depends on it, everything comes from it, and everything returns to it.

He thought that water was the arche of all things.

His reasoning being that life depends on it, everything comes from it, and everything returns to it.

Though it’s an observation that might strike us now as unremarkable or perhaps naïve, in his time it was a radical leap.

It was the first attempt to explain the world through a single natural principle rather than divine will.

It was the first attempt to explain the world through a single natural principle rather than divine will.

His student, Anaximander, went further.

He thought that the underlying reality couldn’t be a substance like water that we encounter in the everyday world.

Instead, he posited something more ethereal: a boundless and infinite reality which he called the apeiron.

He thought that the underlying reality couldn’t be a substance like water that we encounter in the everyday world.

Instead, he posited something more ethereal: a boundless and infinite reality which he called the apeiron.

For Anaximander’s student, Anaximenes, this was too abstract though.

The arche was substantial, sure, but it wasn’t water.

It was air.

The arche was substantial, sure, but it wasn’t water.

It was air.

Not only was air foundational to all life, providing the breath (pneuma) to living things, but it was the source of everything else.

It could transform through rarefaction and condensation, becoming wind, cloud, water, earth, and stone.

It could transform through rarefaction and condensation, becoming wind, cloud, water, earth, and stone.

Together, Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes formed the core of what became the Milesian school of philosophy, defined by their use of observation, argumentation, and natural explanations.

In many ways they were the first scientists.

In many ways they were the first scientists.

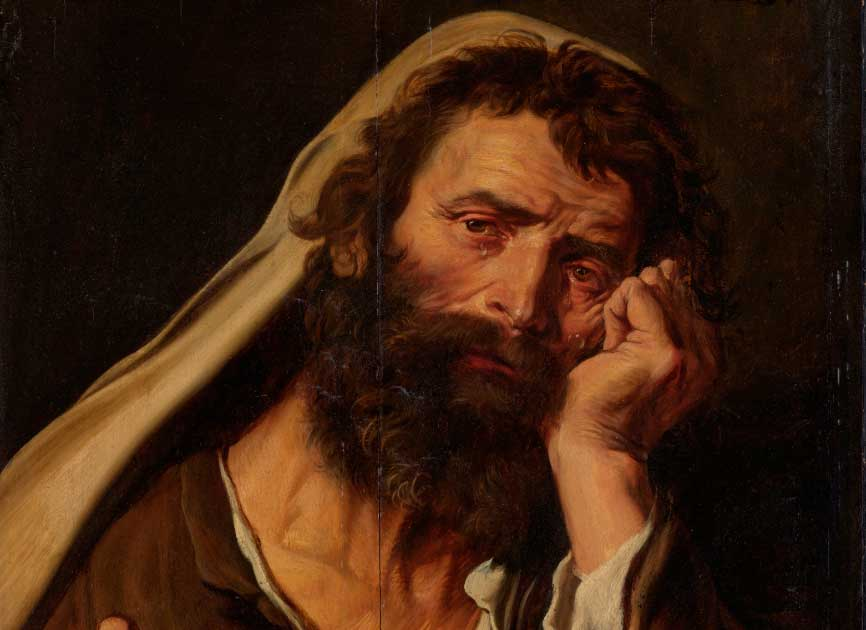

After the Milesians came Heraclitus of Ephesus.

He sought the arche not in substance, but in change.

You may already be familiar with his most famous axiom:

“You cannot step into the same river twice.”

He sought the arche not in substance, but in change.

You may already be familiar with his most famous axiom:

“You cannot step into the same river twice.”

For him, everything was in flux, governed by a hidden rational order called the logos.

To symbolise this ceaseless transformation, he chose fire as the closest expression of the world’s nature.

To symbolise this ceaseless transformation, he chose fire as the closest expression of the world’s nature.

Then came Parmenides. He took the opposite view.

For him, change and flux were just an illusion layered over an eternal and unchanging reality.

Change is impossible, he argued, because:

• What is, is.

• What is not, is not.

• And nothing can come from what is not.

For him, change and flux were just an illusion layered over an eternal and unchanging reality.

Change is impossible, he argued, because:

• What is, is.

• What is not, is not.

• And nothing can come from what is not.

Therefore, nothing really comes into being or passes away.

It’s paradoxical, of course, but Parmenides is prioritising logic over the evidence of the senses.

A major turning point.

It’s paradoxical, of course, but Parmenides is prioritising logic over the evidence of the senses.

A major turning point.

Other thinkers like Empedocles and Anaxagoras tried to resolve this clash between Heraclitus (everything is multiple and changing) and Parmenides (everything is one and eternal).

They developed early theories of matter while attempting to explain change, growth, and decay without recourse to the supernatural.

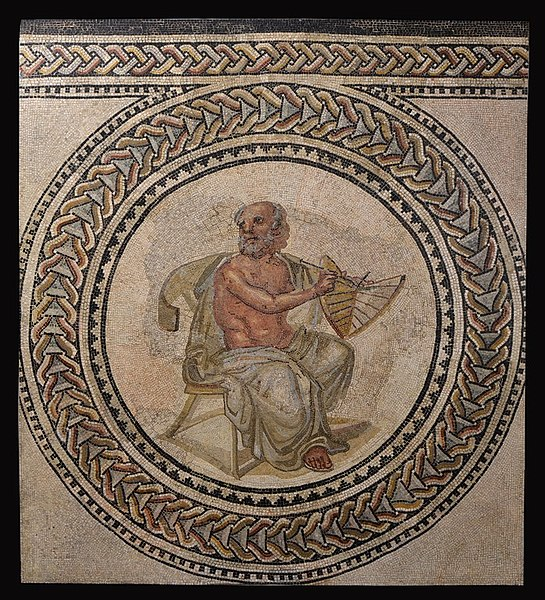

Finally, we have Democritus, who introduced an idea about the material world that’s still with us today.

The universe, he claimed, was made up of indivisible particles moving in the void, which he called atoms.

The universe, he claimed, was made up of indivisible particles moving in the void, which he called atoms.

Democritus’s universe was one of necessity, not providence, where everything, even life and thought, arose from the motion and combination of atoms.

This was the birth of materialism.

This was the birth of materialism.

It’s hard to overstate the radical effect that these thinkers had on shaping how we view the world even up to today.

For the first time, myth had been replaced by reason, the supernatural by the natural.

For the first time, myth had been replaced by reason, the supernatural by the natural.

They sought principles that were universal, debatable, and open to testing, and in doing so, they laid the groundwork for science and philosophy as we know them.

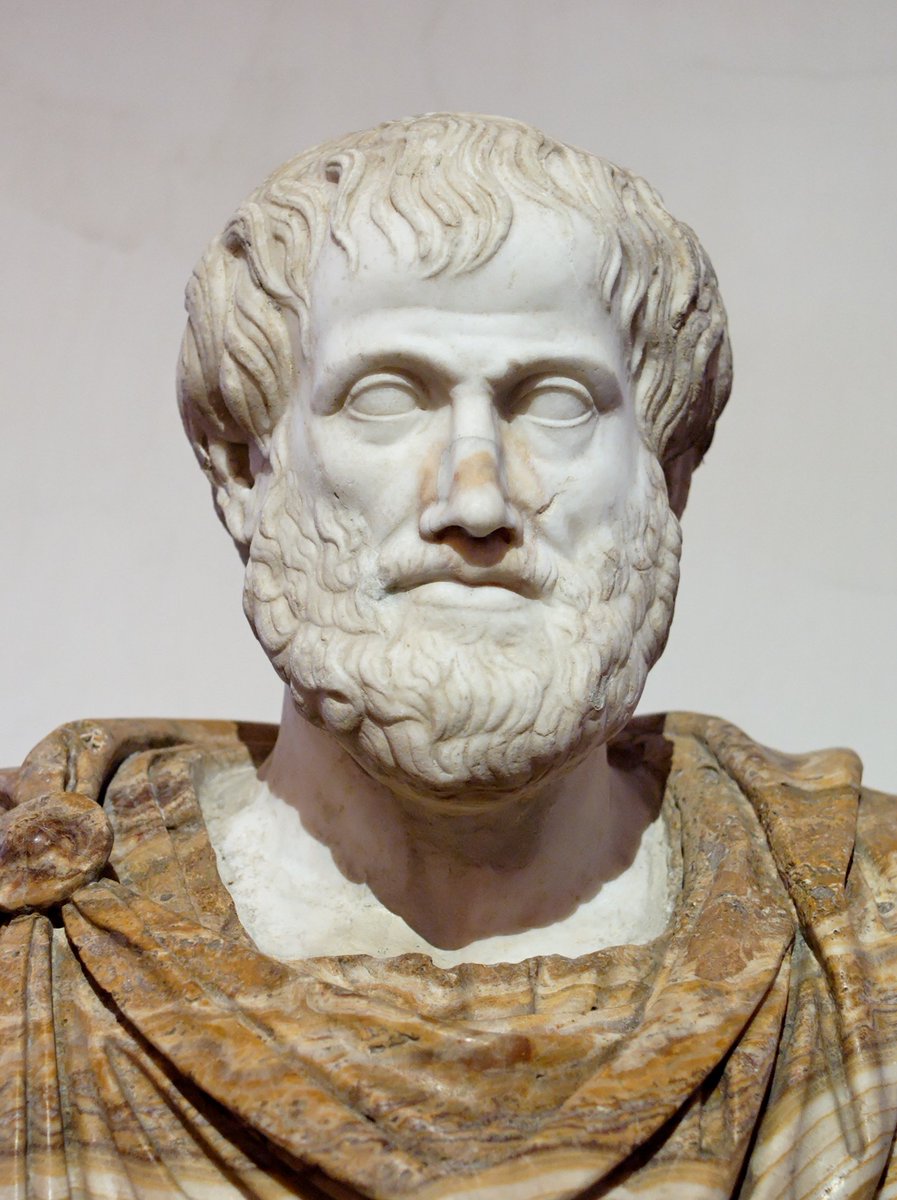

They became known as the Pre-Socratic philosophers, not because they were somehow more primitive than Socrates or the great thinkers who followed, but because they provided the foundation from which Plato and Aristotle could launch their own inquiries.

They were the first to wonder if the world could be apprehended by the powers of our own intellect; that perhaps it was something that we could grasp, understand, and eventually master.

That possibility still animates philosophy and science today.

That possibility still animates philosophy and science today.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh