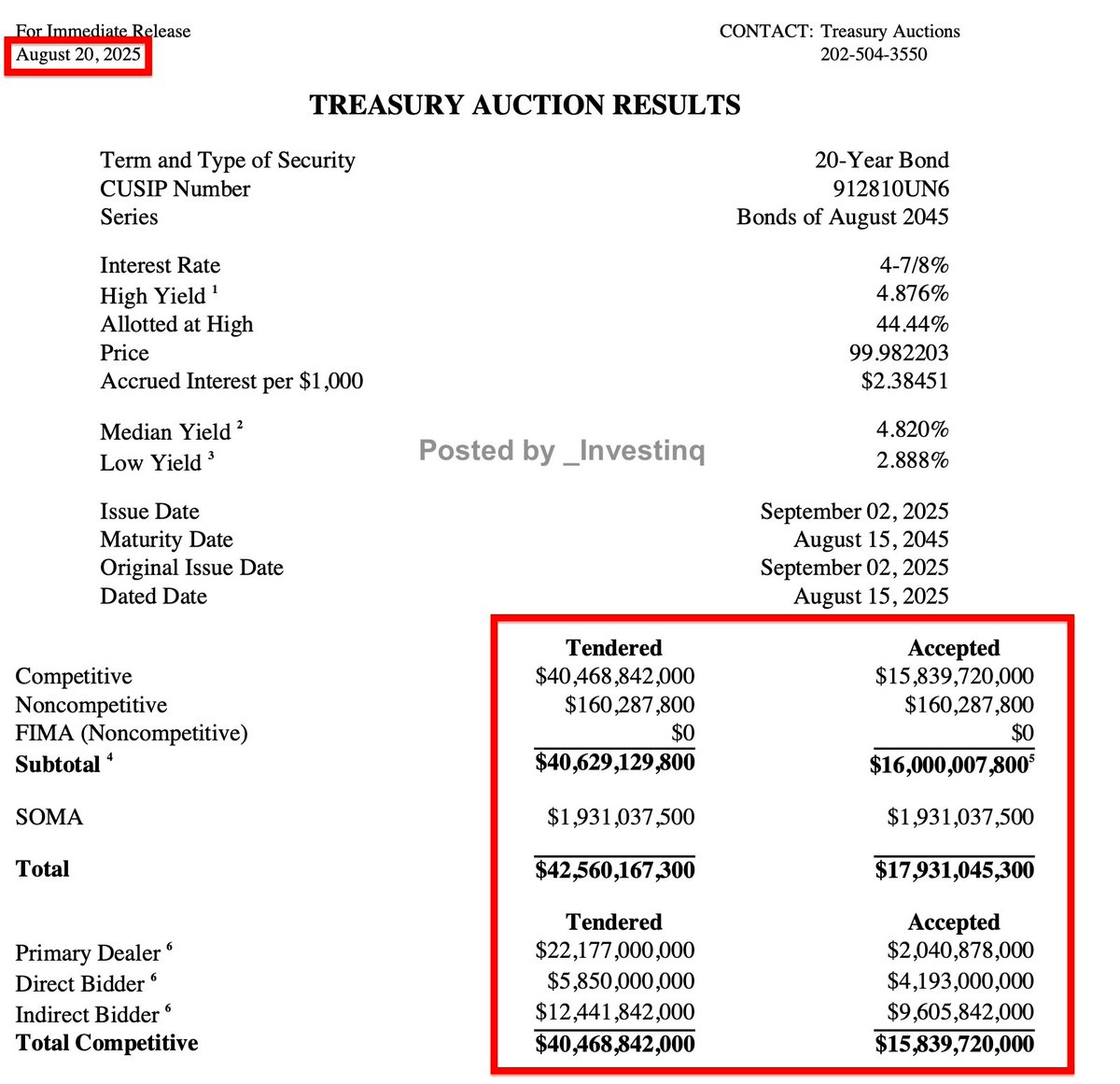

🚨 The U.S. just borrowed $16 billion for 20 years.

Yield came in lower than expected.

But foreign buyers are stepping back, should we be worried?

(a thread)

Yield came in lower than expected.

But foreign buyers are stepping back, should we be worried?

(a thread)

First, what’s a Treasury bond auction? It’s how the U.S. government borrows money.

It issues IOUs (called bonds) to investors who pay cash up front.

In return, those investors get paid interest over time. At the end, they get their full principal back.

It issues IOUs (called bonds) to investors who pay cash up front.

In return, those investors get paid interest over time. At the end, they get their full principal back.

This auction involved 20-year bonds. That means anyone buying is lending money to the government for two decades.

In return, they get paid interest (coupon payments) every 6 months.

At the end of 20 years, the bond “matures” and they get the face value back.

In return, they get paid interest (coupon payments) every 6 months.

At the end of 20 years, the bond “matures” and they get the face value back.

The government offered $16 billion in bonds. That’s the total amount of debt it wanted to sell this round.

The auction lets investors bid on how much they’re willing to lend and at what interest rate they’d accept in return.

This sets the yield.

The auction lets investors bid on how much they’re willing to lend and at what interest rate they’d accept in return.

This sets the yield.

The final “high yield” was 4.876%. That’s the interest rate buyers will get annually.

It’s how much the government agreed to pay to borrow the money.

Higher yield = costlier borrowing for the U.S. Lower yield = stronger demand (investors willing to accept less interest).

It’s how much the government agreed to pay to borrow the money.

Higher yield = costlier borrowing for the U.S. Lower yield = stronger demand (investors willing to accept less interest).

The auction stopped through the expected yield by 0.1 basis points.

Translation: buyers accepted slightly lower yields than markets predicted. A stop-through means demand was strong.

A tail (opposite) means it priced worse than expected. This one? Slight win.

Translation: buyers accepted slightly lower yields than markets predicted. A stop-through means demand was strong.

A tail (opposite) means it priced worse than expected. This one? Slight win.

What’s a basis point? One basis point = 0.01%. So 0.1 basis points = 0.001%.

It sounds microscopic, but when you’re issuing billions in debt, tiny yield differences matter.

Even a 0.001% lower rate can save millions in interest over 20 years.

It sounds microscopic, but when you’re issuing billions in debt, tiny yield differences matter.

Even a 0.001% lower rate can save millions in interest over 20 years.

Next metric: bid-to-cover ratio. This shows how many dollars of bids came in versus what was available.

This time it was 2.54.

That means investors wanted $2.54 for every $1 in bonds offered. Lower than the recent average but still decent.

This time it was 2.54.

That means investors wanted $2.54 for every $1 in bonds offered. Lower than the recent average but still decent.

Think of bid-to-cover like ticket demand. If 100 seats are available and 254 people show up? BTC = 2.54.

That’s good, but last month 279 showed up (BTC = 2.79).

The six-auction average is 2.63 so demand cooled a little but no major red flags.

That’s good, but last month 279 showed up (BTC = 2.79).

The six-auction average is 2.63 so demand cooled a little but no major red flags.

Next up: internals. That’s auction-speak for who bought the bonds. There are 3 groups:

• Indirects = foreign buyers like central banks

• Directs = U.S. institutions like mutual funds and pensions

• Dealers = Wall Street banks

• Indirects = foreign buyers like central banks

• Directs = U.S. institutions like mutual funds and pensions

• Dealers = Wall Street banks

Indirects bought 60.6% of the auction. That’s lower than last month’s 67.4%.

Also the lowest since February 2024.

These are foreign players, Japan, China, Europe, etc. When they step back, it signals less overseas interest in U.S. debt.

Also the lowest since February 2024.

These are foreign players, Japan, China, Europe, etc. When they step back, it signals less overseas interest in U.S. debt.

Directs bought 26.5%, a record high. These are U.S. buyers like pensions, insurance companies, and investment firms.

They picked up the slack left by foreigners.

That’s good news shows local demand remains strong, at least for now.

They picked up the slack left by foreigners.

That’s good news shows local demand remains strong, at least for now.

Dealers took the rest, 12.9%. These are banks like JPMorgan, Citi, etc.

They’re required to buy what’s left over to make the auction work.

Since they only took a small slice, it means most bonds were sold voluntarily not dumped on the banks.

They’re required to buy what’s left over to make the auction work.

Since they only took a small slice, it means most bonds were sold voluntarily not dumped on the banks.

Let’s pause and talk about why auctions matter. The U.S. runs big deficits, it spends more than it earns so it borrows constantly.

Every Treasury auction is a test:

Can we still borrow at low rates? Who’s still willing to lend? How long will they stay that way?

Every Treasury auction is a test:

Can we still borrow at low rates? Who’s still willing to lend? How long will they stay that way?

Also important: when demand is weak, yields have to rise to attract buyers.

That raises borrowing costs for the U.S.

And since Treasury yields set the baseline for almost all other interest rates, everything from mortgage rates to car loans could tick up.

That raises borrowing costs for the U.S.

And since Treasury yields set the baseline for almost all other interest rates, everything from mortgage rates to car loans could tick up.

This auction saw yields fall slightly from July’s 4.935%.

That drop to 4.876% means buyers were satisfied with less return.

Could be because of a recent stock market pullback. When stocks fall, money often flows into safer assets like bonds.

That drop to 4.876% means buyers were satisfied with less return.

Could be because of a recent stock market pullback. When stocks fall, money often flows into safer assets like bonds.

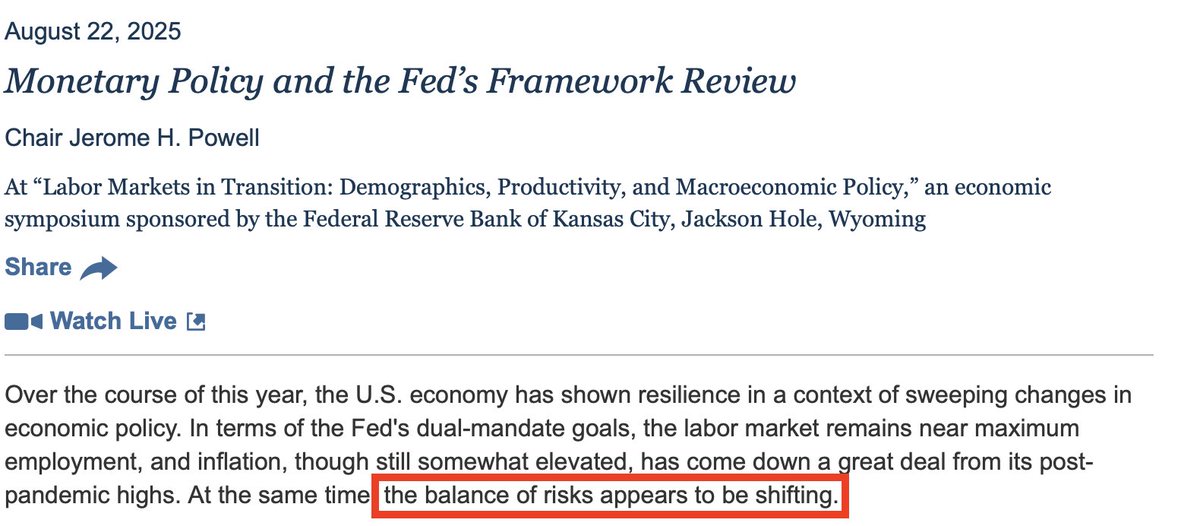

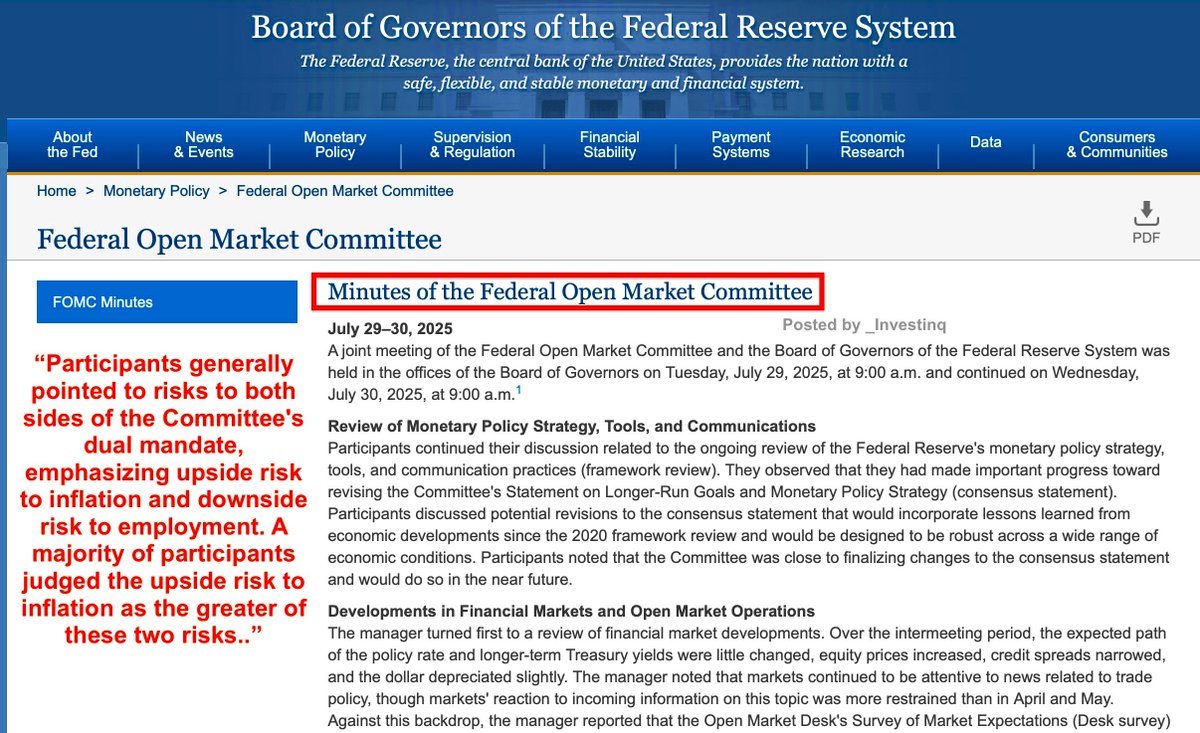

Another reason demand held up: Expectations that the Fed will eventually cut rates.

If investors think interest rates will drop in the future, locking in 4.8% for 20 years suddenly looks pretty good.

It’s a bet on where rates are headed.

If investors think interest rates will drop in the future, locking in 4.8% for 20 years suddenly looks pretty good.

It’s a bet on where rates are headed.

But that foreign pullback (60.6% indirect) is a flag to watch.

If international appetite keeps fading, the Treasury might need to pay higher rates to fill the gap.

That could ripple across markets fast, especially if deficits keep growing.

If international appetite keeps fading, the Treasury might need to pay higher rates to fill the gap.

That could ripple across markets fast, especially if deficits keep growing.

After the auction, markets barely flinched. The 10-year yield edged lower meaning prices went up slightly.

No panic. Traders weren’t shocked.

This was a clean, uncontroversial auction and markets love stability.

No panic. Traders weren’t shocked.

This was a clean, uncontroversial auction and markets love stability.

So what would a bad auction look like?

• Huge tail (yield worse than expected)

• Low bid-to-cover (not enough demand)

• Dealers stuck with too much

• Markets sell off right after

This auction avoided all of that. Solid grade: B+

• Huge tail (yield worse than expected)

• Low bid-to-cover (not enough demand)

• Dealers stuck with too much

• Markets sell off right after

This auction avoided all of that. Solid grade: B+

Bottom line: The U.S. borrowed $16B for 20 years. Buyers showed up. Interest rate was a bit lower than expected.

Foreign demand dipped and domestic demand stepped up.

We live to auction another day.

Foreign demand dipped and domestic demand stepped up.

We live to auction another day.

If you found these insights valuable: Sign up for my FREE newsletter! thestockmarket.news

I hope you've found this thread helpful.

Follow me @_Investinq for more.

Like/Repost the quote below if you can:

Follow me @_Investinq for more.

Like/Repost the quote below if you can:

https://x.com/_investinq/status/1958231966085492743?s=46

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh