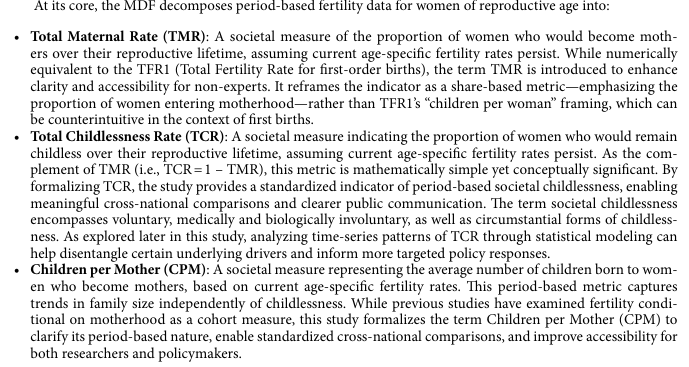

Published today, an important paper proposes a framework dividing total fertility rate into two component parts:

TFR = Total Maternity Rate (TMR) x Children per Mother (CPM)

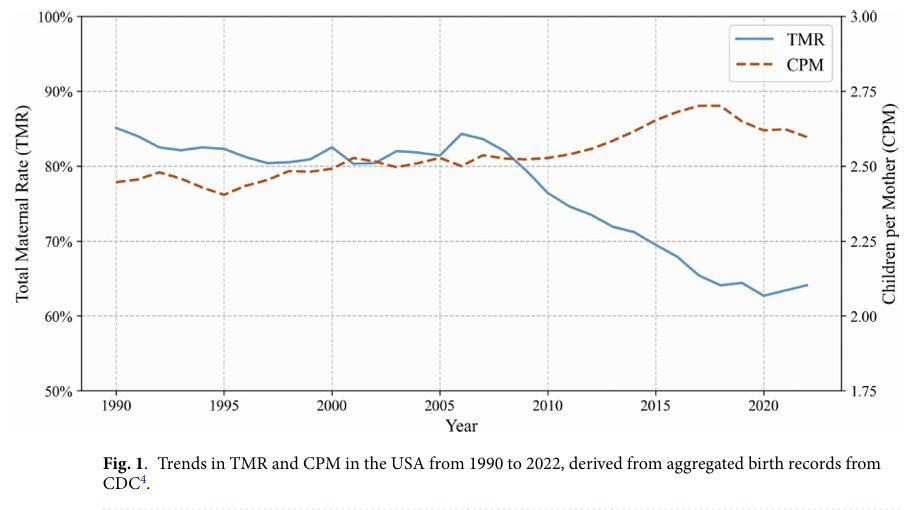

This lens shows that virtually all recent declines in fertility were due to increasing childlessness. 🧵

TFR = Total Maternity Rate (TMR) x Children per Mother (CPM)

This lens shows that virtually all recent declines in fertility were due to increasing childlessness. 🧵

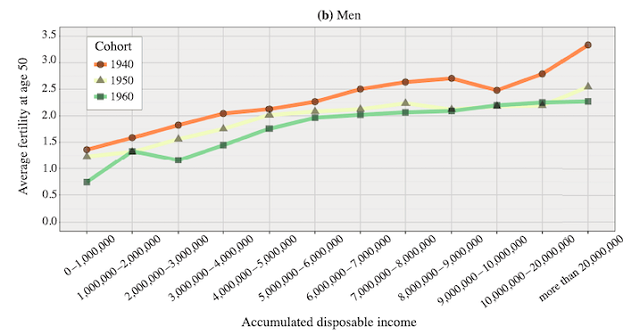

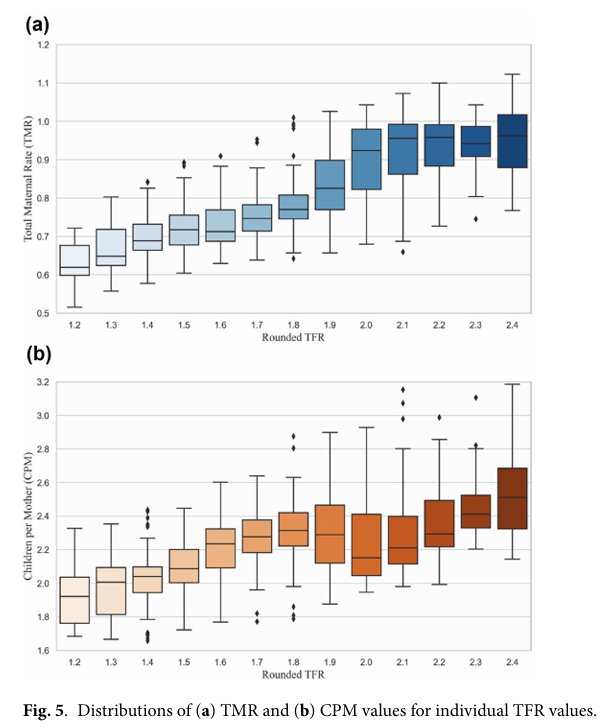

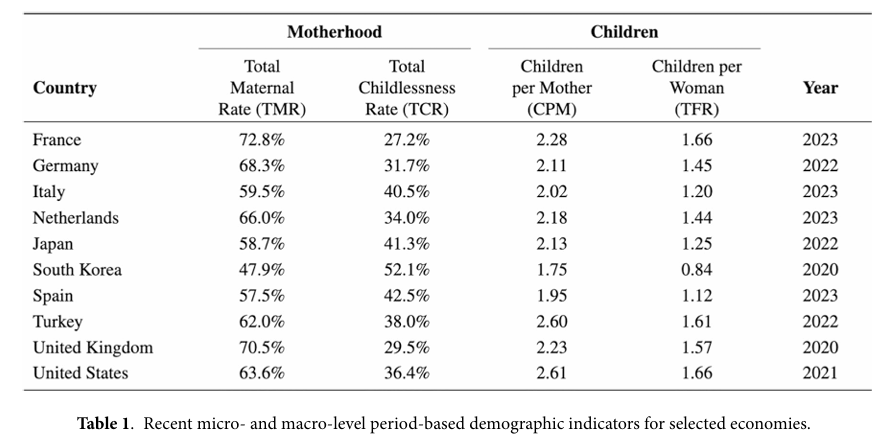

Demographer @StephenJShaw realized that these two components of TFR, the total maternity rate (or equivalently, the childless rate) and children per mother move quite independently of each other.

That means one gets much more information from looking at both parts together. 2/6

That means one gets much more information from looking at both parts together. 2/6

Unsurprisingly, both lower rates of motherhood and smaller family sizes are contributors to the crisis of low birthrates.

But both factors matter since the policies helping people reach parenthood may be very different from the ones supporting or encouraging larger families. 3/6

But both factors matter since the policies helping people reach parenthood may be very different from the ones supporting or encouraging larger families. 3/6

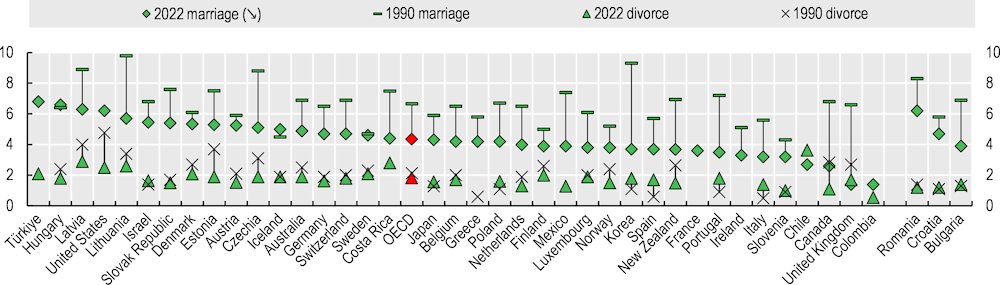

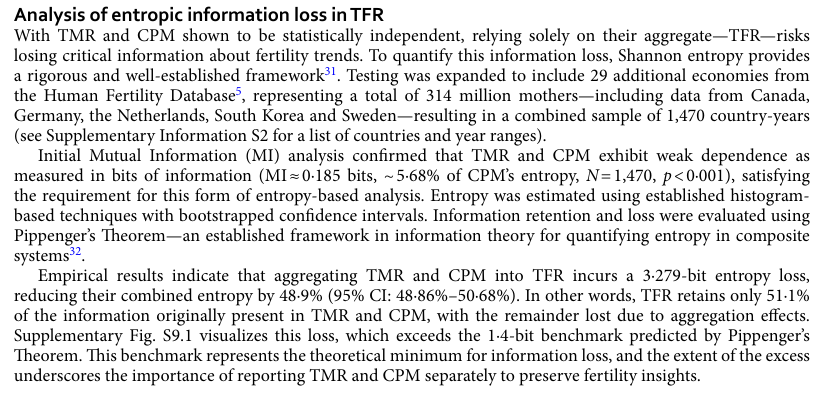

Shaw finds that among developed countries, those with the lowest fertility rates, namely Korea, Japan, Spain and Italy all have much higher rates of childlessness, suggesting that has been a major cause of ultra-low fertility. 4/6

At the same time, the US has had better fertility than other advanced countries in large part because lower rates of motherhood have been compensated for by steadily increasing family sizes.

In the US, a pronatal culture of big families helped counteract rising childlessness! 5/6

In the US, a pronatal culture of big families helped counteract rising childlessness! 5/6

Shaw's work is the culmination of many years of research as he analyzed a staggering amount of data, covering some 314 million mothers across 33 higher-income countries! 6/6

See the full paper here:

nature.com/articles/s4159…

See the full paper here:

nature.com/articles/s4159…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh