When Gods Crossed Borders: The Remarkable Discovery of Vedic Deities in Ancient Syria

How a 3,400-year-old treaty found in Turkey rewrote our understanding of Bronze Age cultural exchange

I. The Accidental Discovery That Changed History

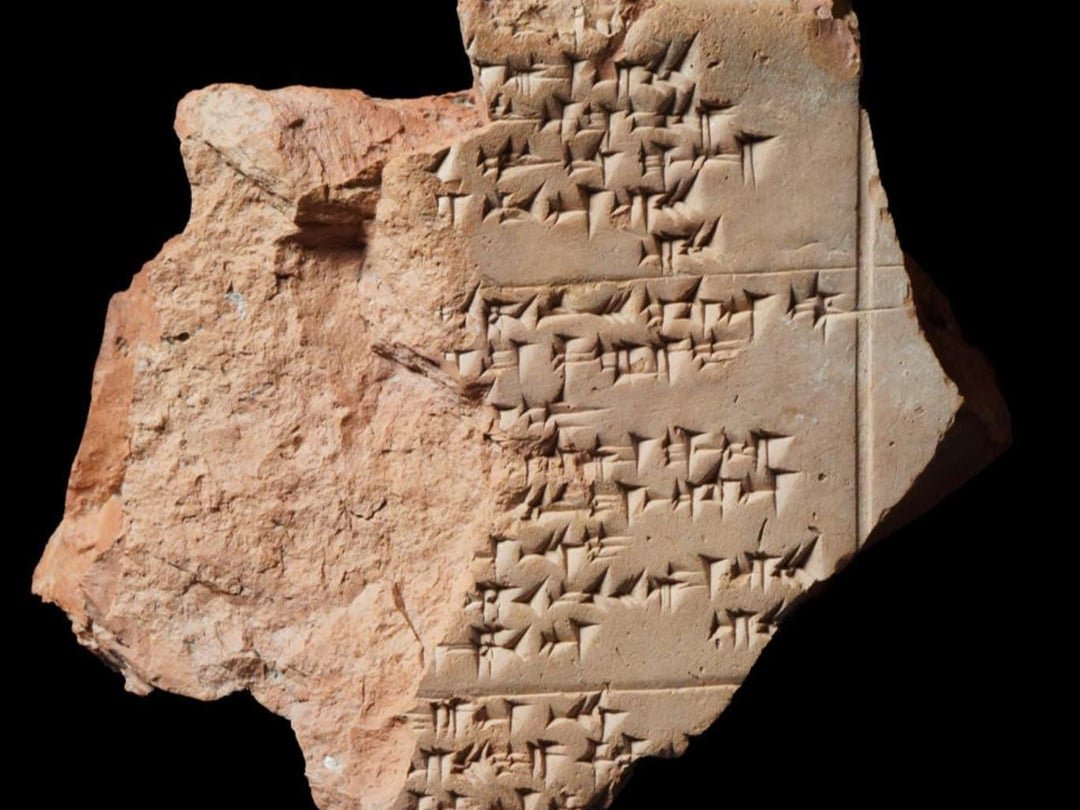

In the spring of 1906, Hugo Winckler was growing frustrated. The German archaeologist had come to the barren hills of central Turkey expecting to uncover Assyrian ruins, but what he found instead seemed to make no sense. The cuneiform tablets emerging from the ancient mound at Bogazköy bore inscriptions in an unknown language, filled with references to peoples and places that didn't appear in any historical record. Local villagers had been using the scattered clay fragments to build walls and repair roads, unaware they were destroying one of archaeology's greatest treasures.

What Winckler had stumbled upon was Hattusa, the lost capital of the Hittite Empire—a Bronze Age superpower that had once ruled from the Black Sea to the borders of Egypt. Over the course of several excavation seasons, his team would unearth more than 25,000 cuneiform tablets, transforming our understanding of the ancient Near East. Among these was a diplomatic archive that revealed the Hittites as masterful negotiators who had corresponded with pharaohs, traded with Mycenaean Greeks, and forged alliances across the known world.

But the most startling discovery lay buried in the fragments of a peace treaty dating to around 1380 BCE. As scholars painstakingly pieced together the broken tablets and began to decipher their contents, they found something that should have been impossible: the names of gods from the Indian subcontinent, invoked as divine witnesses in a diplomatic agreement between two ancient Near Eastern kingdoms. The implications would ripple through academia for generations, challenging everything historians thought they knew about the boundaries between civilizations.

How a 3,400-year-old treaty found in Turkey rewrote our understanding of Bronze Age cultural exchange

I. The Accidental Discovery That Changed History

In the spring of 1906, Hugo Winckler was growing frustrated. The German archaeologist had come to the barren hills of central Turkey expecting to uncover Assyrian ruins, but what he found instead seemed to make no sense. The cuneiform tablets emerging from the ancient mound at Bogazköy bore inscriptions in an unknown language, filled with references to peoples and places that didn't appear in any historical record. Local villagers had been using the scattered clay fragments to build walls and repair roads, unaware they were destroying one of archaeology's greatest treasures.

What Winckler had stumbled upon was Hattusa, the lost capital of the Hittite Empire—a Bronze Age superpower that had once ruled from the Black Sea to the borders of Egypt. Over the course of several excavation seasons, his team would unearth more than 25,000 cuneiform tablets, transforming our understanding of the ancient Near East. Among these was a diplomatic archive that revealed the Hittites as masterful negotiators who had corresponded with pharaohs, traded with Mycenaean Greeks, and forged alliances across the known world.

But the most startling discovery lay buried in the fragments of a peace treaty dating to around 1380 BCE. As scholars painstakingly pieced together the broken tablets and began to decipher their contents, they found something that should have been impossible: the names of gods from the Indian subcontinent, invoked as divine witnesses in a diplomatic agreement between two ancient Near Eastern kingdoms. The implications would ripple through academia for generations, challenging everything historians thought they knew about the boundaries between civilizations.

II. The Treaty That Shouldn't Exist

The peace treaty between Hittite King Suppiluliuma I and the Mitanni ruler Shattiwaza reads like a standard Bronze Age diplomatic document—until it reaches the list of divine witnesses. Alongside the expected Hittite storm gods and Hurrian deities, the text invokes "Mitra-shil, Uruwana-shil, Indar, and Nashatianna." To anyone familiar with Sanskrit literature, these names were unmistakable: Mitra, Varuna, Indra, and the Nasatyas—core deities of the Rig Veda, Hinduism's oldest and most sacred text.

The discovery sent shockwaves through the scholarly world. Here was concrete evidence that Vedic religious concepts had somehow traveled thousands of miles from their presumed homeland in India to the courts of ancient Syria and Turkey. The treaty wasn't just a diplomatic curiosity; it was proof that the ancient world was far more interconnected than anyone had imagined. Trade routes and migration patterns that archaeologists had only theorized about suddenly became tangible, written in cuneiform on clay tablets that had survived nearly three and a half millennia.

The political context made the religious implications even more intriguing. The Mitanni kingdom, which controlled territory across northern Syria and southeastern Turkey, was ruled by an Indo-Aryan elite governing a predominantly Hurrian population. Their kings bore Sanskrit names, their warriors were called by the Sanskrit term "marya" (young warrior), and their horse-training manuals contained Sanskrit numerical terms. The treaty revealed a Bronze Age world where cultural and religious ideas flowed freely across continents, carried by traders, diplomats, and migrating peoples who thought nothing of the boundaries that would later divide East from West.

The peace treaty between Hittite King Suppiluliuma I and the Mitanni ruler Shattiwaza reads like a standard Bronze Age diplomatic document—until it reaches the list of divine witnesses. Alongside the expected Hittite storm gods and Hurrian deities, the text invokes "Mitra-shil, Uruwana-shil, Indar, and Nashatianna." To anyone familiar with Sanskrit literature, these names were unmistakable: Mitra, Varuna, Indra, and the Nasatyas—core deities of the Rig Veda, Hinduism's oldest and most sacred text.

The discovery sent shockwaves through the scholarly world. Here was concrete evidence that Vedic religious concepts had somehow traveled thousands of miles from their presumed homeland in India to the courts of ancient Syria and Turkey. The treaty wasn't just a diplomatic curiosity; it was proof that the ancient world was far more interconnected than anyone had imagined. Trade routes and migration patterns that archaeologists had only theorized about suddenly became tangible, written in cuneiform on clay tablets that had survived nearly three and a half millennia.

The political context made the religious implications even more intriguing. The Mitanni kingdom, which controlled territory across northern Syria and southeastern Turkey, was ruled by an Indo-Aryan elite governing a predominantly Hurrian population. Their kings bore Sanskrit names, their warriors were called by the Sanskrit term "marya" (young warrior), and their horse-training manuals contained Sanskrit numerical terms. The treaty revealed a Bronze Age world where cultural and religious ideas flowed freely across continents, carried by traders, diplomats, and migrating peoples who thought nothing of the boundaries that would later divide East from West.

III. The Lost Kingdom and Its Vedic Kings

The Mitanni kingdom emerged in the 16th century BCE as one of the great powers of its age, controlling the lucrative trade routes that connected Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean. But what made Mitanni unique wasn't just its strategic location—it was the remarkable cultural synthesis that defined its ruling class. Archaeological evidence reveals a society where Indo-Aryan traditions had taken root in Hurrian soil, creating a hybrid civilization that bridged the gap between India and the ancient Near East.

The royal names tell the story most clearly. King Tushratta, who ruled during Mitanni's golden age, bore a name meaning "having an attacking chariot" in Sanskrit. His predecessors included Artashumara ("thinking of cosmic order") and Shatiwaza ("gaining strength"). These weren't borrowed titles or diplomatic appellations—they were genuine Sanskrit names that reflected the Indo-Aryan identity of Mitanni's ruling dynasty. Even more remarkably, the kingdom's military elite maintained Sanskrit terminology for their ranks and equipment, suggesting that Indo-Aryan culture wasn't just a royal affectation but a living tradition that shaped Mitanni society.

This cultural persistence becomes even more significant when we consider the distances involved. The Indo-Aryan ancestors of Mitanni's elite had somehow migrated from Central Asia to the heart of the Near East, maintaining their religious traditions and social customs across thousands of miles. They brought with them not just their gods and their language, but an entire worldview that would influence diplomacy and statecraft in one of the ancient world's most cosmopolitan regions. The Mitanni court became a meeting point where Vedic hymns might have been chanted alongside Hurrian prayers, where Sanskrit terms mingled with Akkadian diplomatic language.

The Mitanni kingdom emerged in the 16th century BCE as one of the great powers of its age, controlling the lucrative trade routes that connected Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean. But what made Mitanni unique wasn't just its strategic location—it was the remarkable cultural synthesis that defined its ruling class. Archaeological evidence reveals a society where Indo-Aryan traditions had taken root in Hurrian soil, creating a hybrid civilization that bridged the gap between India and the ancient Near East.

The royal names tell the story most clearly. King Tushratta, who ruled during Mitanni's golden age, bore a name meaning "having an attacking chariot" in Sanskrit. His predecessors included Artashumara ("thinking of cosmic order") and Shatiwaza ("gaining strength"). These weren't borrowed titles or diplomatic appellations—they were genuine Sanskrit names that reflected the Indo-Aryan identity of Mitanni's ruling dynasty. Even more remarkably, the kingdom's military elite maintained Sanskrit terminology for their ranks and equipment, suggesting that Indo-Aryan culture wasn't just a royal affectation but a living tradition that shaped Mitanni society.

This cultural persistence becomes even more significant when we consider the distances involved. The Indo-Aryan ancestors of Mitanni's elite had somehow migrated from Central Asia to the heart of the Near East, maintaining their religious traditions and social customs across thousands of miles. They brought with them not just their gods and their language, but an entire worldview that would influence diplomacy and statecraft in one of the ancient world's most cosmopolitan regions. The Mitanni court became a meeting point where Vedic hymns might have been chanted alongside Hurrian prayers, where Sanskrit terms mingled with Akkadian diplomatic language.

IV. Deciphering the Sacred Names

When linguists first encountered the divine names in the Hittite-Mitanni treaty, they faced a puzzle that would take decades to fully resolve. The cuneiform script, with its wedge-shaped marks pressed into clay, was never designed to capture the subtle sounds of Sanskrit. Yet somehow, ancient scribes had managed to preserve the essence of Vedic divine names with remarkable accuracy. "Mitra-shil" and "Uruwana-shil" bore the telltale Hurrian plural suffix, but the root names were unmistakably those of the Vedic gods Mitra and Varuna.

The linguistic detective work revealed fascinating insights about how religious concepts traveled across cultures. Indra, the storm god and king of the Vedic pantheon, appeared in the treaty as "Indar"—close enough to suggest direct transmission rather than gradual linguistic evolution. The Nasatyas, the twin horse-gods of the Rig Veda, were rendered as "Nashatianna" with a Hurrian grammatical ending. These weren't approximate translations or local adaptations; they were the actual Sanskrit names, carefully preserved and formally invoked in the most solemn diplomatic contexts.

The preservation of these names suggests something profound about Bronze Age religious practice. The Mitanni rulers didn't just remember their ancestral gods—they considered them powerful enough to guarantee international treaties. In a world where divine wrath was believed to strike down oath-breakers, the invocation of Vedic deities in a Near Eastern treaty represented the ultimate validation of Indo-Aryan religious authority. The gods of the Rig Veda had become diplomatic players on the ancient world's most important stage, their names carrying weight in the corridors of Hittite and Egyptian power.

When linguists first encountered the divine names in the Hittite-Mitanni treaty, they faced a puzzle that would take decades to fully resolve. The cuneiform script, with its wedge-shaped marks pressed into clay, was never designed to capture the subtle sounds of Sanskrit. Yet somehow, ancient scribes had managed to preserve the essence of Vedic divine names with remarkable accuracy. "Mitra-shil" and "Uruwana-shil" bore the telltale Hurrian plural suffix, but the root names were unmistakably those of the Vedic gods Mitra and Varuna.

The linguistic detective work revealed fascinating insights about how religious concepts traveled across cultures. Indra, the storm god and king of the Vedic pantheon, appeared in the treaty as "Indar"—close enough to suggest direct transmission rather than gradual linguistic evolution. The Nasatyas, the twin horse-gods of the Rig Veda, were rendered as "Nashatianna" with a Hurrian grammatical ending. These weren't approximate translations or local adaptations; they were the actual Sanskrit names, carefully preserved and formally invoked in the most solemn diplomatic contexts.

The preservation of these names suggests something profound about Bronze Age religious practice. The Mitanni rulers didn't just remember their ancestral gods—they considered them powerful enough to guarantee international treaties. In a world where divine wrath was believed to strike down oath-breakers, the invocation of Vedic deities in a Near Eastern treaty represented the ultimate validation of Indo-Aryan religious authority. The gods of the Rig Veda had become diplomatic players on the ancient world's most important stage, their names carrying weight in the corridors of Hittite and Egyptian power.

V. The Ancient Highways of Faith

The discovery of Vedic deities in a Syrian treaty forced archaeologists to reconsider their maps of the ancient world. How had religious concepts developed in the Indian subcontinent made their way to the courts of Anatolia and northern Syria? The answer lay in understanding the Bronze Age as an era of unprecedented connectivity, when trade routes and migration patterns created networks of cultural exchange that spanned continents. The famous Uttara Patha, the "northern road" of ancient Indian tradition, was just one strand in a web of highways that connected the Indus Valley to the Mediterranean.

These weren't just commercial arteries—they were conduits for ideas, technologies, and beliefs. Archaeological evidence reveals a Bronze Age world where luxury goods moved alongside religious concepts, where Mesopotamian cylinder seals appeared in Central Asian tombs and Indus Valley weights and measures influenced trade practices from Afghanistan to Syria. The Mitanni kingdom occupied a crucial node in this network, a place where Indo-Aryan traditions encountered and merged with local Hurrian and broader Near Eastern cultures.

The religious implications were staggering. If Vedic deities could be formally invoked in Hittite treaties, what other Hindu concepts might have traveled westward? Scholars began finding Sanskrit horse-training terminology in Mitanni texts, numerical systems that matched Vedic practices, and social structures that paralleled those described in ancient Indian literature. The discovery suggested that the cultural exchange between India and the Near East wasn't a historical accident but part of a sustained pattern of contact that lasted for centuries. Bronze Age globalization had created a world where a Syrian king could swear by Indian gods and expect his oaths to be honored.

The discovery of Vedic deities in a Syrian treaty forced archaeologists to reconsider their maps of the ancient world. How had religious concepts developed in the Indian subcontinent made their way to the courts of Anatolia and northern Syria? The answer lay in understanding the Bronze Age as an era of unprecedented connectivity, when trade routes and migration patterns created networks of cultural exchange that spanned continents. The famous Uttara Patha, the "northern road" of ancient Indian tradition, was just one strand in a web of highways that connected the Indus Valley to the Mediterranean.

These weren't just commercial arteries—they were conduits for ideas, technologies, and beliefs. Archaeological evidence reveals a Bronze Age world where luxury goods moved alongside religious concepts, where Mesopotamian cylinder seals appeared in Central Asian tombs and Indus Valley weights and measures influenced trade practices from Afghanistan to Syria. The Mitanni kingdom occupied a crucial node in this network, a place where Indo-Aryan traditions encountered and merged with local Hurrian and broader Near Eastern cultures.

The religious implications were staggering. If Vedic deities could be formally invoked in Hittite treaties, what other Hindu concepts might have traveled westward? Scholars began finding Sanskrit horse-training terminology in Mitanni texts, numerical systems that matched Vedic practices, and social structures that paralleled those described in ancient Indian literature. The discovery suggested that the cultural exchange between India and the Near East wasn't a historical accident but part of a sustained pattern of contact that lasted for centuries. Bronze Age globalization had created a world where a Syrian king could swear by Indian gods and expect his oaths to be honored.

VI. Echoes Across Time

Today, the tablets containing the Hittite-Mitanni treaty rest in museums across Turkey and Europe, their cuneiform inscriptions offering silent testimony to one of history's most remarkable cultural encounters. The discovery continues to reshape our understanding of the ancient world, challenging the neat boundaries that once divided Eastern and Western civilizations. In an age when cultural interaction is often seen as a modern phenomenon, the treaty reminds us that humans have always been remarkably adept at sharing ideas across vast distances.

The implications extend far beyond academic history. In our current era of globalization debates and cultural anxiety, the Mitanni kingdom offers a different model—a society that successfully integrated foreign traditions without losing its essential character. The Indo-Aryan elite of Mitanni didn't impose their culture on their Hurrian subjects; instead, they created a synthesis that drew strength from multiple traditions. Their diplomatic language borrowed from Akkadian, their religious practices incorporated local deities alongside Vedic gods, and their social structures adapted to Near Eastern political realities.

Perhaps most remarkably, the treaty suggests that ancient peoples understood something we sometimes forget: that the gods of one culture can become the guardians of another, that religious traditions gain rather than lose power when they cross borders and adapt to new circumstances. The Vedic deities invoked in that Syrian treaty weren't diminished by their exile from India—they were transformed into universal principles that could guarantee oaths between peoples who had never seen the Ganges or heard the Rig Veda chanted. In the end, the Hittite-Mitanni treaty is more than a historical curiosity; it's evidence that the human capacity for cultural synthesis and mutual understanding is as old as civilization itself.

Today, the tablets containing the Hittite-Mitanni treaty rest in museums across Turkey and Europe, their cuneiform inscriptions offering silent testimony to one of history's most remarkable cultural encounters. The discovery continues to reshape our understanding of the ancient world, challenging the neat boundaries that once divided Eastern and Western civilizations. In an age when cultural interaction is often seen as a modern phenomenon, the treaty reminds us that humans have always been remarkably adept at sharing ideas across vast distances.

The implications extend far beyond academic history. In our current era of globalization debates and cultural anxiety, the Mitanni kingdom offers a different model—a society that successfully integrated foreign traditions without losing its essential character. The Indo-Aryan elite of Mitanni didn't impose their culture on their Hurrian subjects; instead, they created a synthesis that drew strength from multiple traditions. Their diplomatic language borrowed from Akkadian, their religious practices incorporated local deities alongside Vedic gods, and their social structures adapted to Near Eastern political realities.

Perhaps most remarkably, the treaty suggests that ancient peoples understood something we sometimes forget: that the gods of one culture can become the guardians of another, that religious traditions gain rather than lose power when they cross borders and adapt to new circumstances. The Vedic deities invoked in that Syrian treaty weren't diminished by their exile from India—they were transformed into universal principles that could guarantee oaths between peoples who had never seen the Ganges or heard the Rig Veda chanted. In the end, the Hittite-Mitanni treaty is more than a historical curiosity; it's evidence that the human capacity for cultural synthesis and mutual understanding is as old as civilization itself.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh