The Enlightenment was fuelled by coffee.

Voltaire was even said to consume up to 50 cups a day!

Here's the story of how a strange and bitter drink from the East found its way to England and became the lifeblood of modern thought... 🧵

Voltaire was even said to consume up to 50 cups a day!

Here's the story of how a strange and bitter drink from the East found its way to England and became the lifeblood of modern thought... 🧵

It’s fair to say that when Western merchants traversing Ottoman lands in the 17th century encountered the drink the locals called “Coffa” they weren’t impressed.

One remarked that it was as “blacke as soote, and tasting not much unlike it”

One remarked that it was as “blacke as soote, and tasting not much unlike it”

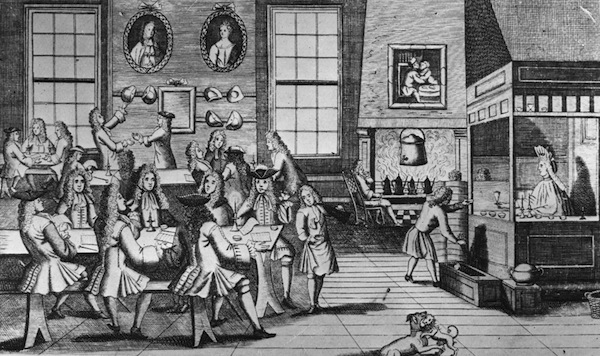

Though the taste may not have drawn them in initially, the culture did.

In Constantinople and Aleppo, coffee was consumed in coffee houses where men would meet each other, chat and socialise the days away.

It reminded the merchants of the taverns back in London.

In Constantinople and Aleppo, coffee was consumed in coffee houses where men would meet each other, chat and socialise the days away.

It reminded the merchants of the taverns back in London.

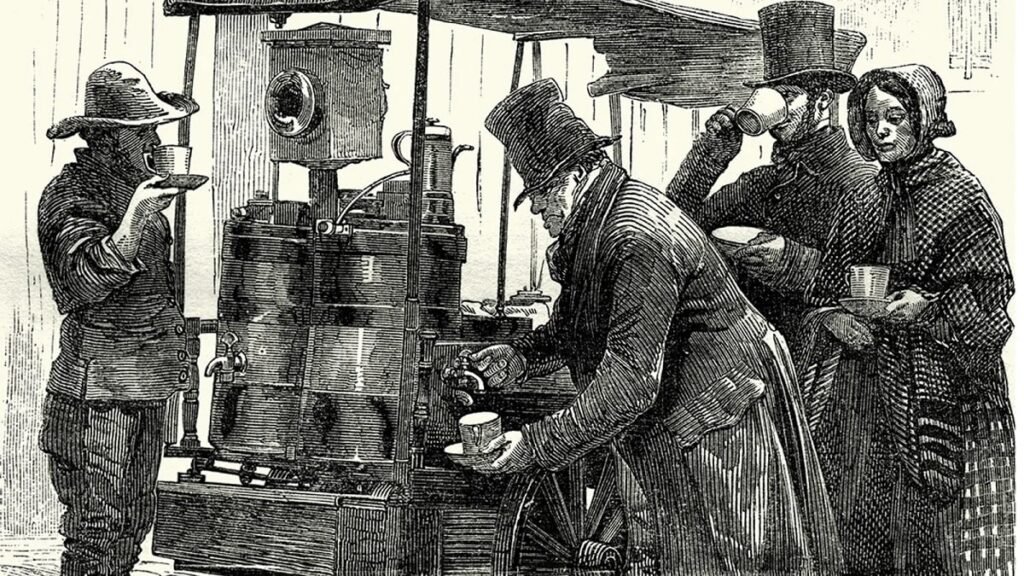

Soon, as coffee made its way back West with other goods like opium and tobacco, coffee houses like the ones those merchants encountered in the Ottoman world began to spring up all over England.

The first ever coffee house was opened in 1650 in Oxford.

Academics crowded in, energised by a drink that sharpened their minds instead of dulling them. For the first time, conversation went late into the night without staggering into drunkenness.

Academics crowded in, energised by a drink that sharpened their minds instead of dulling them. For the first time, conversation went late into the night without staggering into drunkenness.

And in 1652, the first coffee house in London was opened by Pasqua Rosee, an Armenian servant who had travelled with his English master from Smyrna.

It stood in St Michael’s Alley, Cornhill, and quickly became a sensation as Londoners flocked to taste this exotic new drink.

It stood in St Michael’s Alley, Cornhill, and quickly became a sensation as Londoners flocked to taste this exotic new drink.

Unlike taverns and alehouses, which were mostly frequented by working men, labourers, and sailors, and were often noisy and disorderly, coffee houses offered a place to conduct business, trade news, read and distribute pamphlets, and have debates.

By the latter half of the 17th century, they were opening up all over London, drawing in people from all across the social spectrum, where the boundaries of class would temporarily dissolve.

Indeed, the Abbé Prévost marvelled:

“What a lesson to see a lord or two, a baronet, a shoemaker, a tailor, a wine merchant, and a few others of the same stamp, poring over the same newspapers. Truly the coffee houses are the seats of English liberty.”

“What a lesson to see a lord or two, a baronet, a shoemaker, a tailor, a wine merchant, and a few others of the same stamp, poring over the same newspapers. Truly the coffee houses are the seats of English liberty.”

That men could gather to discuss philosophy, science, politics, and trade outside the confines of court, church, or universitycaptured the spirit of the age.

These were the values of the Enlightenment itself: open debate, shared knowledge, and the testing of ideas in public.

These were the values of the Enlightenment itself: open debate, shared knowledge, and the testing of ideas in public.

Not only that, but it was cheap too. A penny for entry which would usually include the first cup of coffee. It was this that earned coffee houses the nickname “Penny Universities”

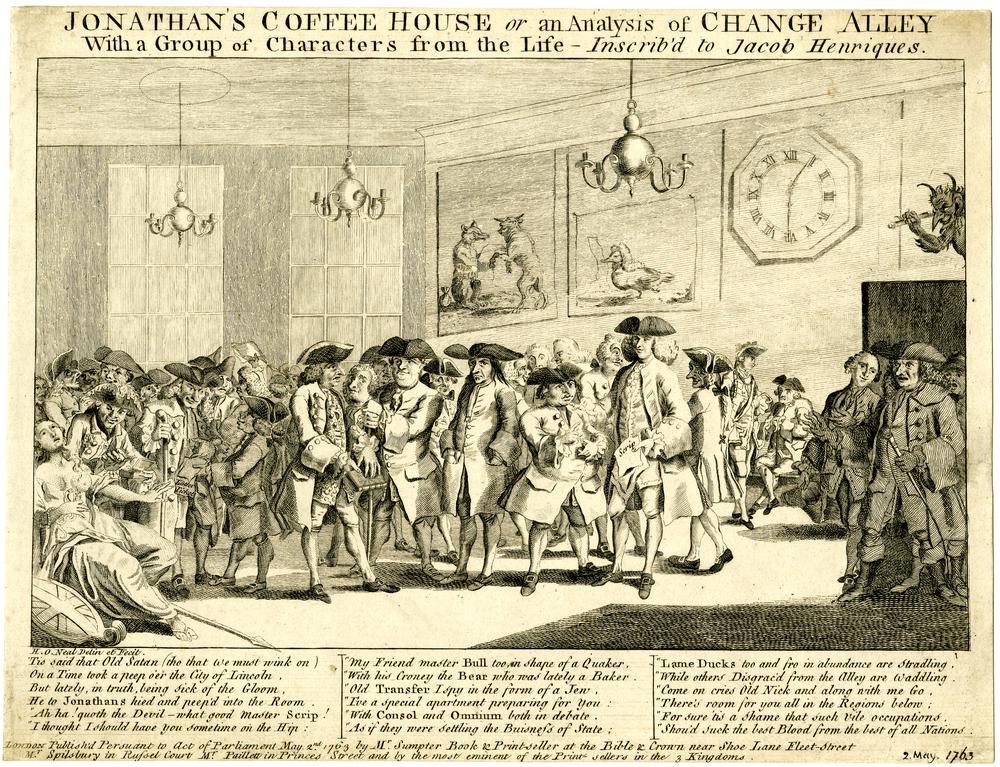

Each house had its own character:

· The Grecian, where Newton and Halley argued over science.

· Lloyd’s, where shipping merchants built the world’s great insurance market.

· Jonathan’s, where stock-jobbers laid the foundations of modern finance.

· The Grecian, where Newton and Halley argued over science.

· Lloyd’s, where shipping merchants built the world’s great insurance market.

· Jonathan’s, where stock-jobbers laid the foundations of modern finance.

Knowledge spread faster than ever.

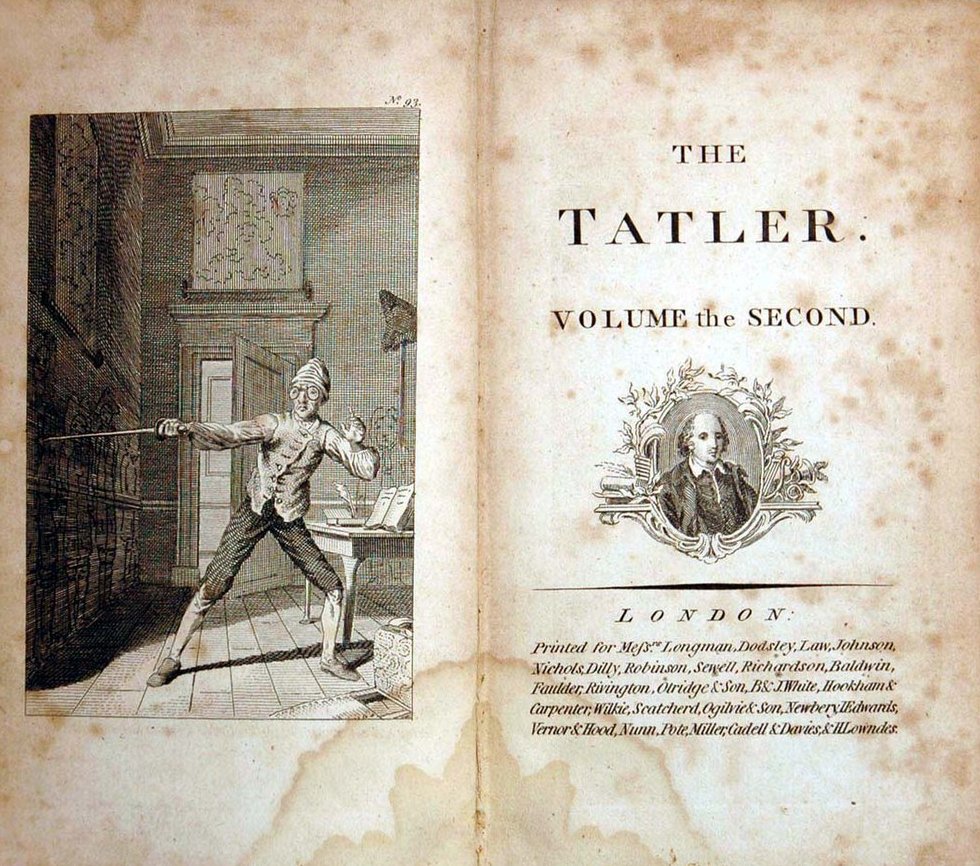

Pamphlets like The Tatler and The Spectator were written for a coffee-house audience.

Grabbing a coffee meant keeping your finger on the pulse and breaking news often reached the tables before it hit the press.

Pamphlets like The Tatler and The Spectator were written for a coffee-house audience.

Grabbing a coffee meant keeping your finger on the pulse and breaking news often reached the tables before it hit the press.

We are used to the idea of an informed public, chatting politics in pubs, bars, at work or even down at the gym.

But in the 17th century this was something entirely new. Coffee houses became the first places where such open discussion could flourish.

But in the 17th century this was something entirely new. Coffee houses became the first places where such open discussion could flourish.

The philosopher Jürgen Habermas later called them the seedbeds of the “public sphere” — the beginnings of public opinion itself.

Thus, in the 17th century, a critical, engaged, and self-conscious public emerged.

Thus, in the 17th century, a critical, engaged, and self-conscious public emerged.

By the early 18th century, coffee houses were at their peak. Buzzing hubs of trade, news, ideas. Incubators of Enlightenment ideals and culture.

But as fashions change, and tea became the drink of choice since it was cheaper and easier to prepare at home, they slowly declined.

But as fashions change, and tea became the drink of choice since it was cheaper and easier to prepare at home, they slowly declined.

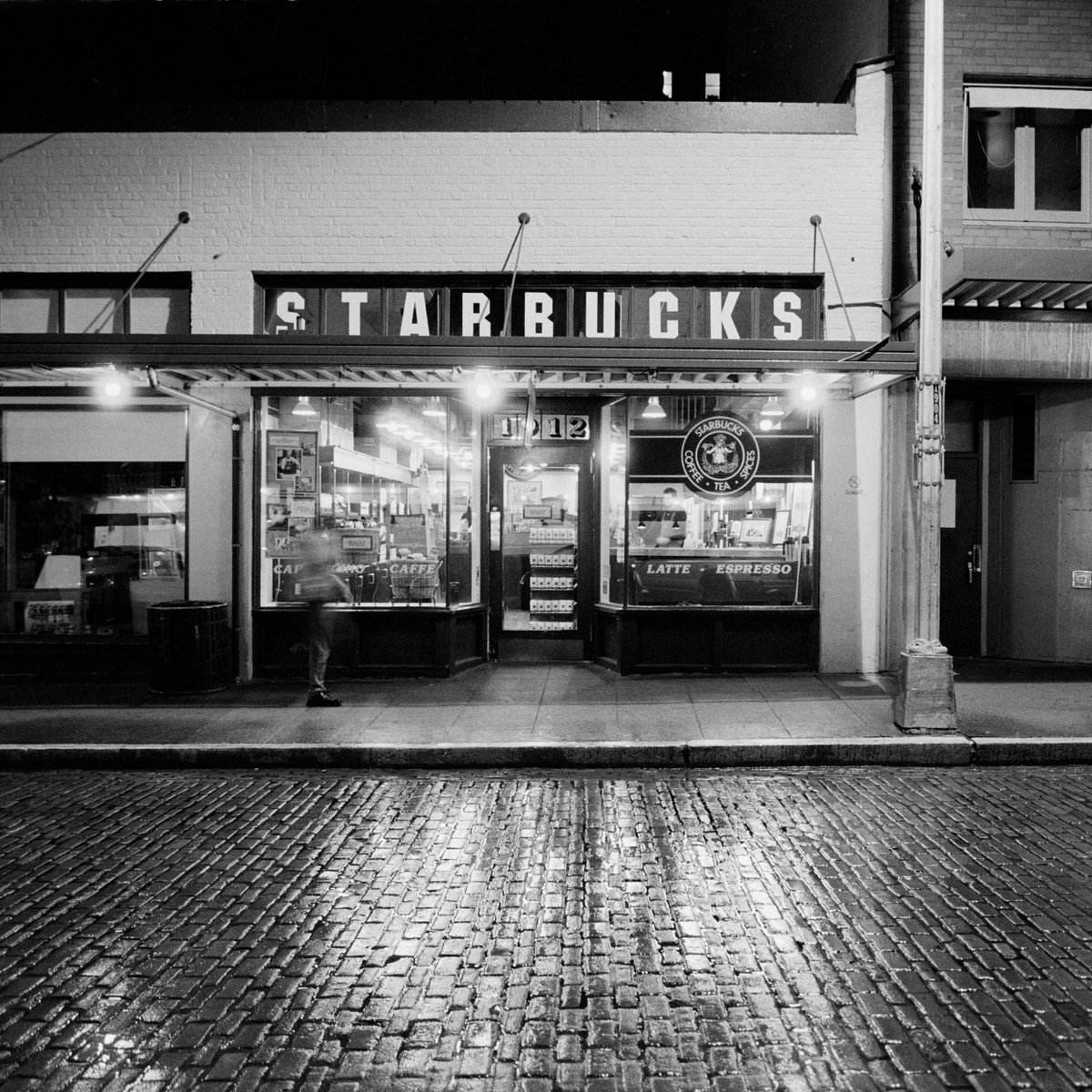

Their spirit lived on, however— in newspapers, learned societies, and trading floors— and coffee itself still holds a central position in social life as a drink that gathers people together in cafes and homes around the world.

The age of the coffee house had passed, but its legacy endured.

From the bitter “Coffa” of Constantinople to the crowded houses of Oxford and London, the ideas that changed the world were brewed in cups of coffee.

From the bitter “Coffa” of Constantinople to the crowded houses of Oxford and London, the ideas that changed the world were brewed in cups of coffee.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this then please consider supporting me by sharing this post!

If you enjoyed this then please consider supporting me by sharing this post!

https://x.com/laertiusx/status/1958952382726852774?s=46

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh