Ok, I was asked by 5+ people to weigh in, so here we go.

Quick answer: This is wrong. China currently has much more dispatchable capacity (MW) than peak load AND much more capability to generate power (MWh) than is consumed by customers, both by large margins.

Longer Answer:🧵

Quick answer: This is wrong. China currently has much more dispatchable capacity (MW) than peak load AND much more capability to generate power (MWh) than is consumed by customers, both by large margins.

Longer Answer:🧵

https://twitter.com/michaeljmcnair/status/1959134225447182439

Installed Capacity vs. Peak Load:

At the end of 1H 2025, China had roughly 2071 GW of dispatchable capacity (thermal, hydro, nuclear, batteries).

Meanwhile, national peak load on 17 July 2025 hit a new high of 1508 GW.

Thus, reserve capacity margin during the recent annual demand peak was ~37%. That's dispatchable capacity...not counting intermittent generators. Of course, in reality, the demand peak arrived at a period when solar generators WERE available (afternoon on a sunny, hot, midsummer day). China now has over 1000 GW of solar (and 650 GW of wind). So some of them were performing at this time, but it's a good conservative practice to not include them in a reserve margin estimation.

Most of the time, load is WELL below 1508 GW and effective reserve margins are higher. In mild evenings of shoulder seasons with no particular heating or cooling demand, reserve margins are at their highest, probably over 100%(?) But in the context of considering a data center that needs to operate 24/7/365, we might as well look at the annual peak as our limiter.

At the end of 1H 2025, China had roughly 2071 GW of dispatchable capacity (thermal, hydro, nuclear, batteries).

Meanwhile, national peak load on 17 July 2025 hit a new high of 1508 GW.

Thus, reserve capacity margin during the recent annual demand peak was ~37%. That's dispatchable capacity...not counting intermittent generators. Of course, in reality, the demand peak arrived at a period when solar generators WERE available (afternoon on a sunny, hot, midsummer day). China now has over 1000 GW of solar (and 650 GW of wind). So some of them were performing at this time, but it's a good conservative practice to not include them in a reserve margin estimation.

Most of the time, load is WELL below 1508 GW and effective reserve margins are higher. In mild evenings of shoulder seasons with no particular heating or cooling demand, reserve margins are at their highest, probably over 100%(?) But in the context of considering a data center that needs to operate 24/7/365, we might as well look at the annual peak as our limiter.

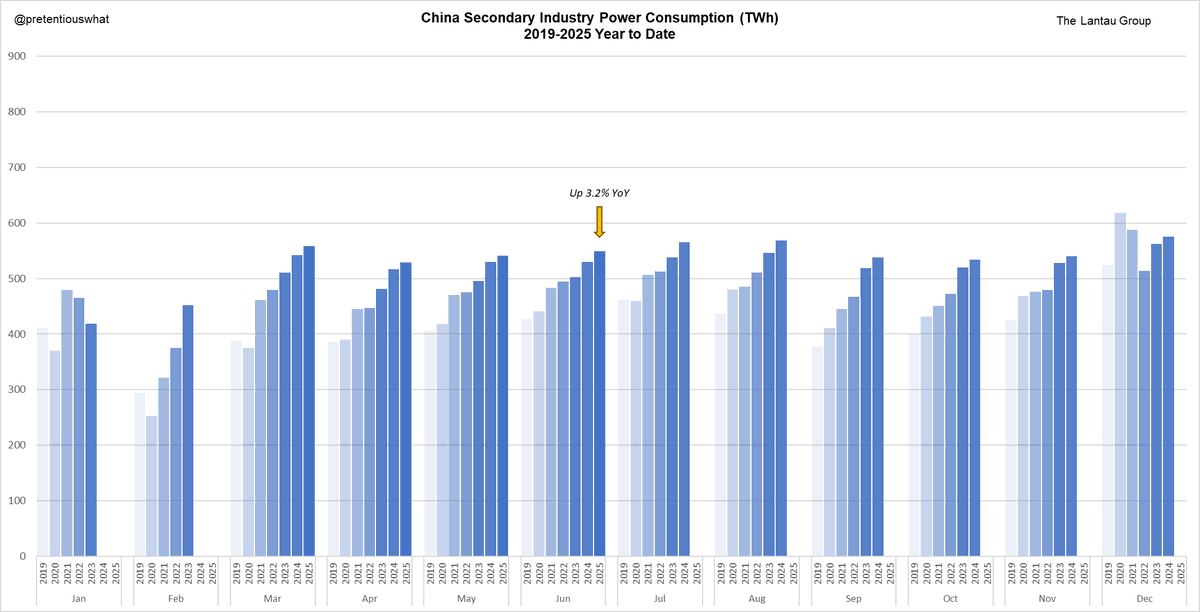

Generation vs. Consumption and Surplus:

Generation and consumption will be balanced, yes (after accounting for plent self-use and line losses). But if the generators COULD generate more, then that means you have a lot of unused potential. This is the case in China.

In 2024, the average annual operating numbers for China's thermal fleet of 1444 GW were just 3442 hours. That works out to an annual capacity factor of ~39% (the average is higher for coal and lower for gas). There's nothing stopping them from generating more, except the power consumption needs of the Chinese economy were already met by other generation sources.

Frankly, these thermal generators could easily generate 2x their current operating hours and it wouldn't be a problem at all (except for the carbon peaking target of course!). If the annual capacity factor of the thermal fleet doubled to a hardly-unreasonable 78%, it would yield an additional 4,970 TWh annually. That's more than the entire annual consumption of the USA.

Yes, China is squatting on an entire USA's worth of untapped power generation solely within the unused capacity of its current thermal fleet.

Additionally the curtailment of wind and solar means there are times throughout the year when these generators are producing power that the grid can't accept - thus it is wasted. National curtailment rates were around 3% last year, but much higher in individual provinces (and they've been rising in 2025).

Generation and consumption will be balanced, yes (after accounting for plent self-use and line losses). But if the generators COULD generate more, then that means you have a lot of unused potential. This is the case in China.

In 2024, the average annual operating numbers for China's thermal fleet of 1444 GW were just 3442 hours. That works out to an annual capacity factor of ~39% (the average is higher for coal and lower for gas). There's nothing stopping them from generating more, except the power consumption needs of the Chinese economy were already met by other generation sources.

Frankly, these thermal generators could easily generate 2x their current operating hours and it wouldn't be a problem at all (except for the carbon peaking target of course!). If the annual capacity factor of the thermal fleet doubled to a hardly-unreasonable 78%, it would yield an additional 4,970 TWh annually. That's more than the entire annual consumption of the USA.

Yes, China is squatting on an entire USA's worth of untapped power generation solely within the unused capacity of its current thermal fleet.

Additionally the curtailment of wind and solar means there are times throughout the year when these generators are producing power that the grid can't accept - thus it is wasted. National curtailment rates were around 3% last year, but much higher in individual provinces (and they've been rising in 2025).

What About on the Provincial Level?

Despite the national oversupply of both capacity and generation potential, individual provinces might still struggly with local undersupply. Some provinces use way more power than they can produce locally and are reliant on cross-provincial imports from power-abundant provinces to make up the difference. But the grid doesn't connect to everywhere at once (physical limitations) nor are the market mechanisms necessarily set up yet to facilitate easy cross-region power trade (policy limitations). This can create issues that can only be fixed long-term by more investments in the grid and deepening of power market reform.

For example, in 2022 Sichuan's power supply was revealed to be quite vulnerable to droughts because it relied so heavily on local hydropower and hardly had any import capacity. When the local hydropower failed, the power went out. Other provinces that use or import hydropower were also affected. In that case, it didn't really matter that there was surplus generation capacity in Inner Mongolia; it couldn't be transported to Sichuan or Chongqing.

[Actually, even Sichuan's own power couldn't be sold in Sichuan. Some of its giant hydropower facilities were export-only and couldn't really connect to the local grid anyway.]

So, if you are looking to site an energy-intensive industrial facility in China, you might now prioritize building in a region with an abundant *non-intermittent* capacity base like Inner Mongolia. Sichuan used to be viewed as a province with abundant, stable power supply, because hydropower was very cheap and considered minimally variable. With the higher risk of droughts, Sichuan has lost some attractiveness for steel or aluminum producers (or data center operators, for that matter).

If you previously built a facility in Sichuan, or Hubei, or another hydropower-dependent region, you might scoff at the idea that China is oversupplied with abundant power, because you've personally faced hydropower-related disruptions. These two things are true at the same time: A. China is nationally oversuppled with power, which distributes to most provinces on a local level too, but B. China's hydropower-dependent regions face increasing uncertainty because of how droughts affect their capacity base (and are thus now building a ton of backup power and new grid interconnects).

Despite the national oversupply of both capacity and generation potential, individual provinces might still struggly with local undersupply. Some provinces use way more power than they can produce locally and are reliant on cross-provincial imports from power-abundant provinces to make up the difference. But the grid doesn't connect to everywhere at once (physical limitations) nor are the market mechanisms necessarily set up yet to facilitate easy cross-region power trade (policy limitations). This can create issues that can only be fixed long-term by more investments in the grid and deepening of power market reform.

For example, in 2022 Sichuan's power supply was revealed to be quite vulnerable to droughts because it relied so heavily on local hydropower and hardly had any import capacity. When the local hydropower failed, the power went out. Other provinces that use or import hydropower were also affected. In that case, it didn't really matter that there was surplus generation capacity in Inner Mongolia; it couldn't be transported to Sichuan or Chongqing.

[Actually, even Sichuan's own power couldn't be sold in Sichuan. Some of its giant hydropower facilities were export-only and couldn't really connect to the local grid anyway.]

So, if you are looking to site an energy-intensive industrial facility in China, you might now prioritize building in a region with an abundant *non-intermittent* capacity base like Inner Mongolia. Sichuan used to be viewed as a province with abundant, stable power supply, because hydropower was very cheap and considered minimally variable. With the higher risk of droughts, Sichuan has lost some attractiveness for steel or aluminum producers (or data center operators, for that matter).

If you previously built a facility in Sichuan, or Hubei, or another hydropower-dependent region, you might scoff at the idea that China is oversupplied with abundant power, because you've personally faced hydropower-related disruptions. These two things are true at the same time: A. China is nationally oversuppled with power, which distributes to most provinces on a local level too, but B. China's hydropower-dependent regions face increasing uncertainty because of how droughts affect their capacity base (and are thus now building a ton of backup power and new grid interconnects).

But What Happened in 2021?

This is ancient history at this point, but the power shortages in Q3 2021 were not caused by a lack of power generation capacity - but by expensive coal and inflexible market mechanisms.

At the time, coal-fired power generators had to absorb high fuels costs from the mostly-liberalized coal market, but were restricted in how much money they could recoup by raising power rates. After many months of losses, generators literally ran out of money to buy coal, were sick of generating at a loss, and shut down their plants. Pandemonium ensued and industrial power supply was curtailed in 20+ provinces. The NDRC responded by increasing the supply of coal (directing state miners to dig more coal) and liberalizing the price of power to make it more market-driven (essentially, allowing power prices to rise). We wrote about this extensively at the time.

On a personal note, this was one of the first incidents that started earning me broader publicity to talk about Chinese power markets in international media. An unfortunate incident that was quite personally beneficial for my career development.

I say this is ancient history because at this point, the power markets are much more deregulated, allowing cost-passthrough much more smoothly. I'd be shocked if we ever had a market failure via that mechanism ever again. But it was an instructive and fascinating episode about the perils of overly-cautious deregulation...it wouldn't have happened under the fully-regulated policy regime, nor would it have happened under a fully market-based regime. It was the hybrid system that messed things up.

This is ancient history at this point, but the power shortages in Q3 2021 were not caused by a lack of power generation capacity - but by expensive coal and inflexible market mechanisms.

At the time, coal-fired power generators had to absorb high fuels costs from the mostly-liberalized coal market, but were restricted in how much money they could recoup by raising power rates. After many months of losses, generators literally ran out of money to buy coal, were sick of generating at a loss, and shut down their plants. Pandemonium ensued and industrial power supply was curtailed in 20+ provinces. The NDRC responded by increasing the supply of coal (directing state miners to dig more coal) and liberalizing the price of power to make it more market-driven (essentially, allowing power prices to rise). We wrote about this extensively at the time.

On a personal note, this was one of the first incidents that started earning me broader publicity to talk about Chinese power markets in international media. An unfortunate incident that was quite personally beneficial for my career development.

I say this is ancient history because at this point, the power markets are much more deregulated, allowing cost-passthrough much more smoothly. I'd be shocked if we ever had a market failure via that mechanism ever again. But it was an instructive and fascinating episode about the perils of overly-cautious deregulation...it wouldn't have happened under the fully-regulated policy regime, nor would it have happened under a fully market-based regime. It was the hybrid system that messed things up.

What Does This Mean for Data Centers in China?

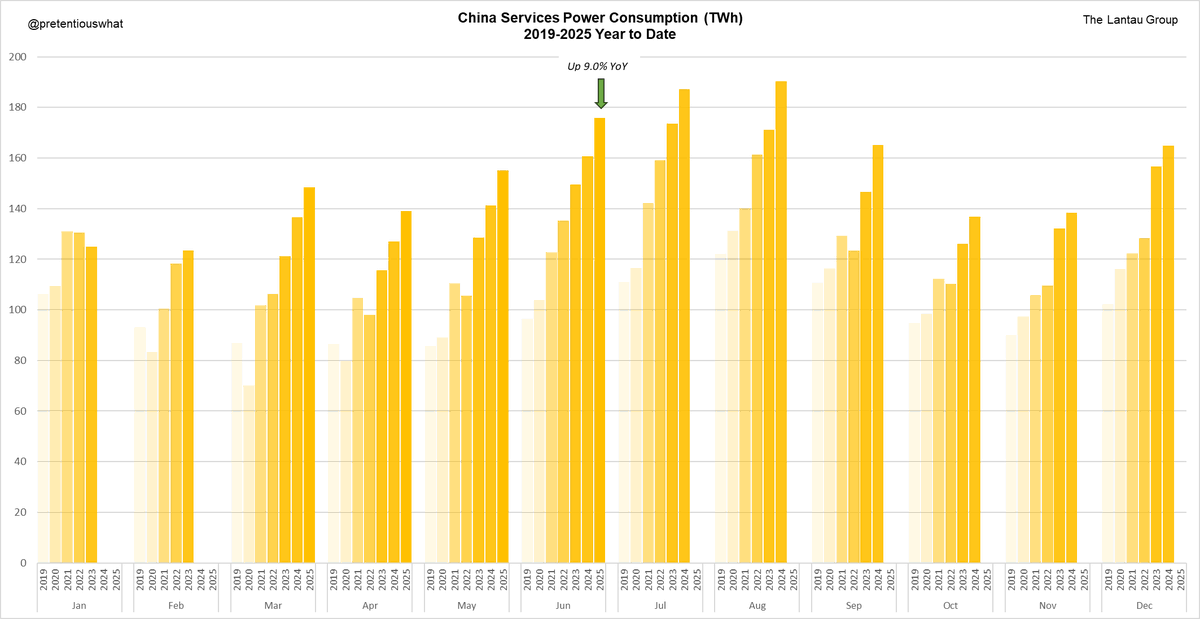

Electricity supply-- whether in MW terms or in MWh terms -- is not a barrier to scaling up data centers in China. There's a LOT of reserve margin -- much more than would be considered economically efficient in more market-driven power systems like the US -- AND a lot of space to operate existing assets more to meet rising consumption...even before considering the huge ongoing capacity buildout. This is why @ruima recently wrote that data center operators in China consider power to be a "solved" problem.

More broadly, this highlights an interesting moment in the overcapacity and capital efficiency debate. Many power markets in the world would consider a 15-25% reserve margin to be sufficient -- and 37% to be unncessarily high. And no power plant operator hopes to build a power plant and use it just 39% of the time...Market purists would surely consider China's develoment of power assets in this way to be excessive and wasteful deployment of capital.

Yes, domestic power demand was growing rapidly, even before the AI boom, and this surplus infrastructure probably could have been absorbed within a few years, but you could argue that means they were built a few years too early. In the interim, that capital could have been used for something else, right? Wouldn't it have been more capital-efficient to build just enough, just in time?

And yet.

In 2025, power systems built to maximize capital efficiency pre-boom by building just enough just in time now find themselves scrambling and straining. Sure, they'll probably figure out a solution as well. Markets are good at that. But it'll take some precious time, and it's going to a strain.

Meanwhile, the country that overbuilt its assets and deployed its capital 'inefficiently' will be rewarded by being well positioned to rapidly absorb this unforecasted power demand spike. China's power system will easily stretch (and already is now) to accomodate the AI data center boom.

Luck? All according to plan? Or the just rewards that come to the prepared...? 🤔 I'll leave that to you guys.

- End

Electricity supply-- whether in MW terms or in MWh terms -- is not a barrier to scaling up data centers in China. There's a LOT of reserve margin -- much more than would be considered economically efficient in more market-driven power systems like the US -- AND a lot of space to operate existing assets more to meet rising consumption...even before considering the huge ongoing capacity buildout. This is why @ruima recently wrote that data center operators in China consider power to be a "solved" problem.

More broadly, this highlights an interesting moment in the overcapacity and capital efficiency debate. Many power markets in the world would consider a 15-25% reserve margin to be sufficient -- and 37% to be unncessarily high. And no power plant operator hopes to build a power plant and use it just 39% of the time...Market purists would surely consider China's develoment of power assets in this way to be excessive and wasteful deployment of capital.

Yes, domestic power demand was growing rapidly, even before the AI boom, and this surplus infrastructure probably could have been absorbed within a few years, but you could argue that means they were built a few years too early. In the interim, that capital could have been used for something else, right? Wouldn't it have been more capital-efficient to build just enough, just in time?

And yet.

In 2025, power systems built to maximize capital efficiency pre-boom by building just enough just in time now find themselves scrambling and straining. Sure, they'll probably figure out a solution as well. Markets are good at that. But it'll take some precious time, and it's going to a strain.

Meanwhile, the country that overbuilt its assets and deployed its capital 'inefficiently' will be rewarded by being well positioned to rapidly absorb this unforecasted power demand spike. China's power system will easily stretch (and already is now) to accomodate the AI data center boom.

Luck? All according to plan? Or the just rewards that come to the prepared...? 🤔 I'll leave that to you guys.

- End

Sources:

Installed capacity 1H 2025: nea.gov.cn/20250723/d7a5d…

Battery capacity 1H 2025:

nea.gov.cn/20250731/83ffa…

Peak load 17 July 2025:

nea.gov.cn/20250731/d34b8…

Operating hours by generator type 2024:

nea.gov.cn/20250121/097bf…

Rising curtailment rates 2025:

finance.sina.com.cn/wm/2025-06-04/…

Summary of 2022 hydropower crisis (yours truly)

lantaugroup.com/publications/d…

Implications of increased volatility in hydropower generation post Sichuan 2022 (yours truly)

cwrrr.org/opinions/what-…

Summaries of 2021 coal supply shortage and subsequent reforms (me again)

lantaugroup.com/publications/d…

lantaugroup.com/publications/d…

Installed capacity 1H 2025: nea.gov.cn/20250723/d7a5d…

Battery capacity 1H 2025:

nea.gov.cn/20250731/83ffa…

Peak load 17 July 2025:

nea.gov.cn/20250731/d34b8…

Operating hours by generator type 2024:

nea.gov.cn/20250121/097bf…

Rising curtailment rates 2025:

finance.sina.com.cn/wm/2025-06-04/…

Summary of 2022 hydropower crisis (yours truly)

lantaugroup.com/publications/d…

Implications of increased volatility in hydropower generation post Sichuan 2022 (yours truly)

cwrrr.org/opinions/what-…

Summaries of 2021 coal supply shortage and subsequent reforms (me again)

lantaugroup.com/publications/d…

lantaugroup.com/publications/d…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh