1/ For generations, men far greater than I have sought to name the source of the West’s supremacy. In its essence, the answer is the uniqueness of the European peoples. Wherever European man has set foot, he has transformed the world, shaping wilderness into cities, tribes into nations, and myth into history.

No less have men sought to explain why the West now declines. The truth is equally plain to anyone who still possesses the capacity for honest thought. Europeans are being displaced in their own homelands. Civilizations are not sustained by slogans or institutions alone. They are carried by blood, by the living continuity of a people. When that people dwindles, society corrodes, and when it is replaced, the civilization ceases to exist.

The men of old knew this instinctively, for they lived beneath the eyes of their ancestors. A name was not a casual designation but a sacred burden, a banner of memory carried forward through time. To disgrace one’s line was to wound one’s very being; to ennoble it was to prove oneself the spearpoint of descent, the flowering of all that had gone before. Each generation stood within this chain, compelled to honor what had been received, yet also pressed by the desire to surpass it. In this there arose a tension deeper than philosophy, a law inscribed in blood itself: the obligation to remain a son of the clan, and the longing to stand apart as a man whose name would echo after his death.

It was from this tension that Europe drew her distinction among civilizations. In India, men were bound within castes where greatness meant the perfection of a role already fixed, conformity raised to a principle of eternity. In China, the weight of Confucian propriety pressed the individual into the service of family and empire until personality itself became a shadow cast by hierarchy. In Japan, courage and discipline were exalted in the figure of the samurai, but his nobility ended in self-extinction before his lord; he could die with beauty, but he died faceless, and no sagas were sung of him.

Europe alone preserved another order, in which the individual did not vanish into the collective but rose above it as its crown. Homer sang not of a people dissolved into anonymity but of Achilles, whose wrath bent the fate of armies. The tragedians of Athens carried this further, showing how the choices of a single king could reverberate through time and overturn the destinies of nations. And in the North, the sagas of Iceland and the legends of the Volsungs gave immortality to men who defied both kin and fate, standing forth from the tribe with such force that their names became indistinguishable from the destiny of their people.

No less have men sought to explain why the West now declines. The truth is equally plain to anyone who still possesses the capacity for honest thought. Europeans are being displaced in their own homelands. Civilizations are not sustained by slogans or institutions alone. They are carried by blood, by the living continuity of a people. When that people dwindles, society corrodes, and when it is replaced, the civilization ceases to exist.

The men of old knew this instinctively, for they lived beneath the eyes of their ancestors. A name was not a casual designation but a sacred burden, a banner of memory carried forward through time. To disgrace one’s line was to wound one’s very being; to ennoble it was to prove oneself the spearpoint of descent, the flowering of all that had gone before. Each generation stood within this chain, compelled to honor what had been received, yet also pressed by the desire to surpass it. In this there arose a tension deeper than philosophy, a law inscribed in blood itself: the obligation to remain a son of the clan, and the longing to stand apart as a man whose name would echo after his death.

It was from this tension that Europe drew her distinction among civilizations. In India, men were bound within castes where greatness meant the perfection of a role already fixed, conformity raised to a principle of eternity. In China, the weight of Confucian propriety pressed the individual into the service of family and empire until personality itself became a shadow cast by hierarchy. In Japan, courage and discipline were exalted in the figure of the samurai, but his nobility ended in self-extinction before his lord; he could die with beauty, but he died faceless, and no sagas were sung of him.

Europe alone preserved another order, in which the individual did not vanish into the collective but rose above it as its crown. Homer sang not of a people dissolved into anonymity but of Achilles, whose wrath bent the fate of armies. The tragedians of Athens carried this further, showing how the choices of a single king could reverberate through time and overturn the destinies of nations. And in the North, the sagas of Iceland and the legends of the Volsungs gave immortality to men who defied both kin and fate, standing forth from the tribe with such force that their names became indistinguishable from the destiny of their people.

2/ To strive for renown was never simply to indulge pride or to advance the clan by cunning calculation. It was to place oneself before the eyes of gods and men, to gamble one’s life against time itself. When a man distinguished himself, his triumphs magnified the strength of his kin and secured the continuation of the tribe. Women sought the one whose name resounded louder than the rest, for in him they saw not merely a protector but the very fountain of life renewed. Yet this striving cannot be reduced to what modern science calls reproductive fitness, for the heroic impulse often cut against survival.

Achilles, when offered the choice between a long but obscure life and a short life crowned by glory, chose the latter. His renown would outlive him, and that permanence was of greater worth than longevity. The Norse sagas are filled with men who fought duels or avenged insults that to modern eyes seem trivial, willingly spilling blood and forfeiting safety to preserve honor. These were not careful strategies of adaptation but wagers with eternity itself. They reveal a people who valued the story of their lives more than the continuation of their breath.

And the men themselves spoke in these terms. They did not justify their actions as prudent or useful but as worthy of remembrance. In the Hellenic world the word was kleos, glory or fame, the song that endures after death. In the North it was lof, the praise that lives in speech and memory. Both terms point to the same truth: that life only achieves permanence when it is preserved in the words of others, when it becomes part of the story. A man might perish, but if he had lived greatly his name could not die.

This was the consciousness of saga, the awareness that life itself is speech. The Old Norse saga means “that which is spoken,” the tale that carries a life across generations. In Greek thought, the parallel is logos, a word that means not only “speech” but also “gathering,” “reckoning,” and “order.” In Heraclitus, logos names the hidden harmony of the world, the measure by which all things are disclosed. To live for saga, then, is to live toward speech, to act in such a way that one’s life can be said, that it may be gathered into the memory of the people and aligned with the order of things.

The hero thus became the visible form of the tribe’s continuity. He was not merely a vessel of descent but a figure who gave shape and brilliance to descent. His deeds, once spoken, became part of the people’s hoard of memory. Each saga, whether of Achilles or Sigurd or Beowulf, was a fragment of eternity wrested from the flow of time: to live in such a way was to accept death, yet to defy oblivion.

Achilles, when offered the choice between a long but obscure life and a short life crowned by glory, chose the latter. His renown would outlive him, and that permanence was of greater worth than longevity. The Norse sagas are filled with men who fought duels or avenged insults that to modern eyes seem trivial, willingly spilling blood and forfeiting safety to preserve honor. These were not careful strategies of adaptation but wagers with eternity itself. They reveal a people who valued the story of their lives more than the continuation of their breath.

And the men themselves spoke in these terms. They did not justify their actions as prudent or useful but as worthy of remembrance. In the Hellenic world the word was kleos, glory or fame, the song that endures after death. In the North it was lof, the praise that lives in speech and memory. Both terms point to the same truth: that life only achieves permanence when it is preserved in the words of others, when it becomes part of the story. A man might perish, but if he had lived greatly his name could not die.

This was the consciousness of saga, the awareness that life itself is speech. The Old Norse saga means “that which is spoken,” the tale that carries a life across generations. In Greek thought, the parallel is logos, a word that means not only “speech” but also “gathering,” “reckoning,” and “order.” In Heraclitus, logos names the hidden harmony of the world, the measure by which all things are disclosed. To live for saga, then, is to live toward speech, to act in such a way that one’s life can be said, that it may be gathered into the memory of the people and aligned with the order of things.

The hero thus became the visible form of the tribe’s continuity. He was not merely a vessel of descent but a figure who gave shape and brilliance to descent. His deeds, once spoken, became part of the people’s hoard of memory. Each saga, whether of Achilles or Sigurd or Beowulf, was a fragment of eternity wrested from the flow of time: to live in such a way was to accept death, yet to defy oblivion.

3/ Not every life could be remembered, yet the aspiration to be worthy of remembrance shaped the character of our ancestors. To live greatly was not only to survive, but to live toward death with eyes open, knowing that only in death would life be complete, sealed, and judged. So long as a man lived, his story was unfinished, open to reversal or ruin. At death, his tale was fixed, and the verdict of his people would stand as his immortality or his damnation. Death was therefore not the enemy but the consummating moment, the point at which the shape of a life was revealed.

To live with this awareness was to treat every deed as a line in a tale, to choose actions not for advantage alone but for what was fitting, noble, and “worthy of me.” The Greeks spoke of aretē, excellence, the quality that gave form and brilliance to a life. The Northern peoples spoke of drengskapr, manly virtue, by which one proved oneself not only brave but true. These were not abstractions, but standards by which men measured their deeds against the eternal tribunal of memory.

This consciousness of death and of fame gave form to life itself. Without it, men fall into the half-life of those who think only of safety. And that is precisely the condition of modern man. He believes himself liberated from the past, when in fact he is enslaved by forces he cannot name. He imagines that he has freed himself from the chains of blood, lineage, and duty, when in truth he has only severed himself from meaning. He lives for the moment, never for the eternal. He recoils from destiny, from the discipline of form, from the limits that once shaped men into greatness.

He clings to life as if it were the highest good, fearing death above all, and thereby loses the very thing that gives life its greatness. He achieves safety but forfeits distinction. He becomes interchangeable, faceless. He is not remembered, because nothing he does is worth saying. Surrounded by machines that magnify his reach, his soul withers into inertia, slipping between the animal and the vegetative. Modern man has not transcended the saga; he has fallen beneath it, beneath even the level of those who once lived only to serve their caste or their lord. He is subhuman not through cruelty or savagery, but because his life contains nothing enduring.

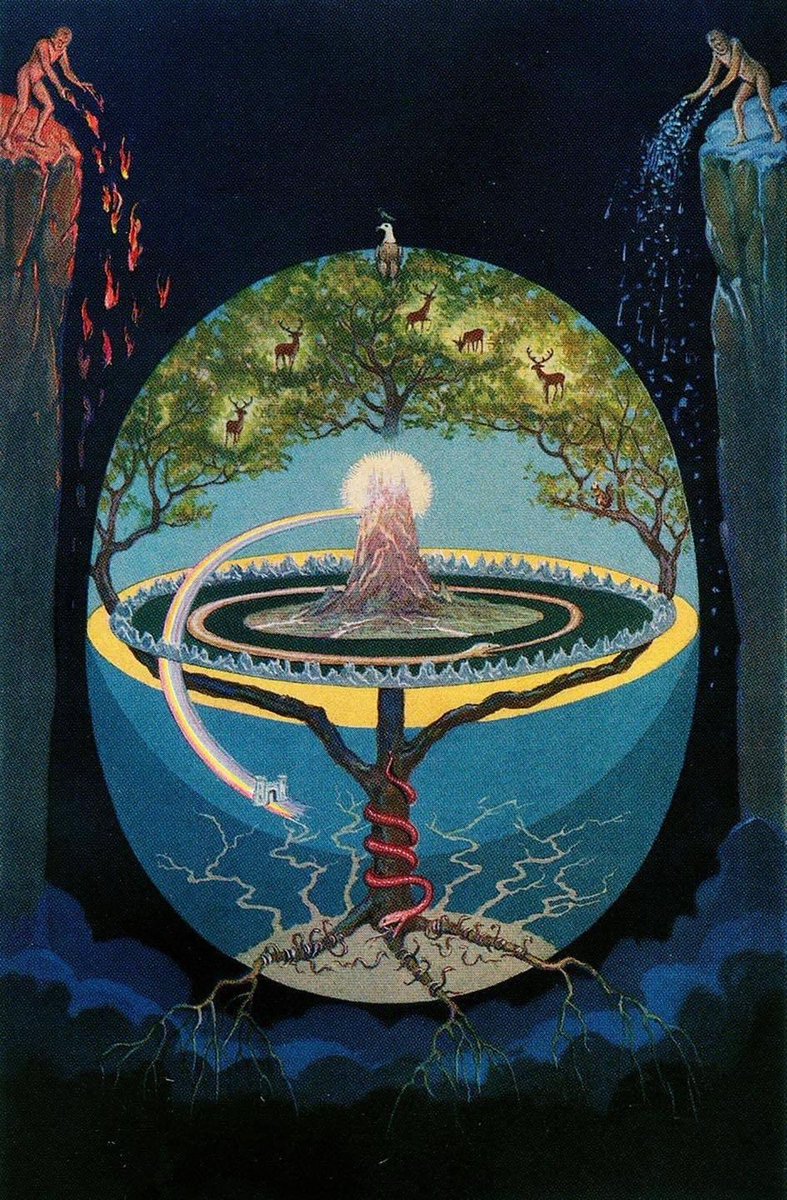

The grandeur of the West was always tragic, for our ancestors knew that nothing endures. Not even the gods could escape fate. The Greeks told of the Moirai, the Fates, who spun and cut the thread of life, binding even Zeus himself. The Norse spoke of an inexorable destiny that determined the end of gods and men alike. Even Yggdrasil, the world-tree, would one day wither. Yet it was precisely because all things were destined to perish that our people sought to wrench permanence from the impermanent, to preserve the fleeting moment in story, to create fragments of eternity in the midst of time.

This is why our ancestors lived toward death, not in despair but in grandeur. For them, death crowned the life, and remembrance bestowed a second existence beyond the grave. This awareness shaped their courage, their poetry, their art, and their politics. They knew the world was passing, but they lived as if glory were eternal. In this tragic wisdom resided the essence of the West.

To live with this awareness was to treat every deed as a line in a tale, to choose actions not for advantage alone but for what was fitting, noble, and “worthy of me.” The Greeks spoke of aretē, excellence, the quality that gave form and brilliance to a life. The Northern peoples spoke of drengskapr, manly virtue, by which one proved oneself not only brave but true. These were not abstractions, but standards by which men measured their deeds against the eternal tribunal of memory.

This consciousness of death and of fame gave form to life itself. Without it, men fall into the half-life of those who think only of safety. And that is precisely the condition of modern man. He believes himself liberated from the past, when in fact he is enslaved by forces he cannot name. He imagines that he has freed himself from the chains of blood, lineage, and duty, when in truth he has only severed himself from meaning. He lives for the moment, never for the eternal. He recoils from destiny, from the discipline of form, from the limits that once shaped men into greatness.

He clings to life as if it were the highest good, fearing death above all, and thereby loses the very thing that gives life its greatness. He achieves safety but forfeits distinction. He becomes interchangeable, faceless. He is not remembered, because nothing he does is worth saying. Surrounded by machines that magnify his reach, his soul withers into inertia, slipping between the animal and the vegetative. Modern man has not transcended the saga; he has fallen beneath it, beneath even the level of those who once lived only to serve their caste or their lord. He is subhuman not through cruelty or savagery, but because his life contains nothing enduring.

The grandeur of the West was always tragic, for our ancestors knew that nothing endures. Not even the gods could escape fate. The Greeks told of the Moirai, the Fates, who spun and cut the thread of life, binding even Zeus himself. The Norse spoke of an inexorable destiny that determined the end of gods and men alike. Even Yggdrasil, the world-tree, would one day wither. Yet it was precisely because all things were destined to perish that our people sought to wrench permanence from the impermanent, to preserve the fleeting moment in story, to create fragments of eternity in the midst of time.

This is why our ancestors lived toward death, not in despair but in grandeur. For them, death crowned the life, and remembrance bestowed a second existence beyond the grave. This awareness shaped their courage, their poetry, their art, and their politics. They knew the world was passing, but they lived as if glory were eternal. In this tragic wisdom resided the essence of the West.

4/ The man who still aspires to greatness lives differently from the mass around him. He does not measure life by its length or by the comforts it can yield, but by the shape it assumes when seen from the end. He lives toward death, not in despair but in clarity, for it is death that seals the story, crowns the life, and gives it form. To live in this way is to treat every deed as part of a tale that others will speak, to act with the knowledge that one’s life will be judged as a whole, and that only the worthy endure in memory.

This mode of life required an intimate knowledge of wyrd, that Northern word for fate, destiny, the web of necessity woven through gods and men alike. Wyrd was not merely a passive doom but the current of reality itself, the stream into which all actions flow. The man of honor sought to place himself within this stream, to align his deeds with its rhythm. He could not escape his fate, but he could meet it nobly, and by so doing shape how it would be told. To act with knowledge of wyrd was not to surrender but to transform necessity into destiny, to make fate itself the instrument of one’s immortality.

The aim was not to live long but to die well. To die with fame, with distinction, with a name that would not perish. Such a death was not defeat but consummation, the sealing of a life into a whole, the transformation of fleeting existence into permanence. The ancients understood that the end of breath was not the end of being, for memory could carry a man beyond the grave. To be remembered, to be sung of, to have one’s name inscribed into the saga, was to attain a second life that time itself could not erase.

Yet in the face of this certainty, our ancestors lived as if glory were eternal. They did not bow before the knowledge of fate but made it the measure of their deeds. They waged their lives against time itself, wrenching from mortality fragments of eternity in story, in song, in remembrance.

Here lies the essence of the Western spirit: to live with the awareness of death and yet to create permanence out of impermanence, to wrest from the passing moment the immortality of a name. The man who accepts this task stands not only as the continuation of his blood but as its crown. He carries forward what he has inherited, adds to it, and by his death leaves it greater than he found it. For he is both the marble and the sculptor, remaking himself through suffering into the shape of greatness. His life becomes a saga, a testament to the truth that though all things perish, greatness endures.

This mode of life required an intimate knowledge of wyrd, that Northern word for fate, destiny, the web of necessity woven through gods and men alike. Wyrd was not merely a passive doom but the current of reality itself, the stream into which all actions flow. The man of honor sought to place himself within this stream, to align his deeds with its rhythm. He could not escape his fate, but he could meet it nobly, and by so doing shape how it would be told. To act with knowledge of wyrd was not to surrender but to transform necessity into destiny, to make fate itself the instrument of one’s immortality.

The aim was not to live long but to die well. To die with fame, with distinction, with a name that would not perish. Such a death was not defeat but consummation, the sealing of a life into a whole, the transformation of fleeting existence into permanence. The ancients understood that the end of breath was not the end of being, for memory could carry a man beyond the grave. To be remembered, to be sung of, to have one’s name inscribed into the saga, was to attain a second life that time itself could not erase.

Yet in the face of this certainty, our ancestors lived as if glory were eternal. They did not bow before the knowledge of fate but made it the measure of their deeds. They waged their lives against time itself, wrenching from mortality fragments of eternity in story, in song, in remembrance.

Here lies the essence of the Western spirit: to live with the awareness of death and yet to create permanence out of impermanence, to wrest from the passing moment the immortality of a name. The man who accepts this task stands not only as the continuation of his blood but as its crown. He carries forward what he has inherited, adds to it, and by his death leaves it greater than he found it. For he is both the marble and the sculptor, remaking himself through suffering into the shape of greatness. His life becomes a saga, a testament to the truth that though all things perish, greatness endures.

5/ If you’d like to read this in full outside of X, or listen to the audio version, follow the link below.

chadcrowley.substack.com/p/fragments-of…

chadcrowley.substack.com/p/fragments-of…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh