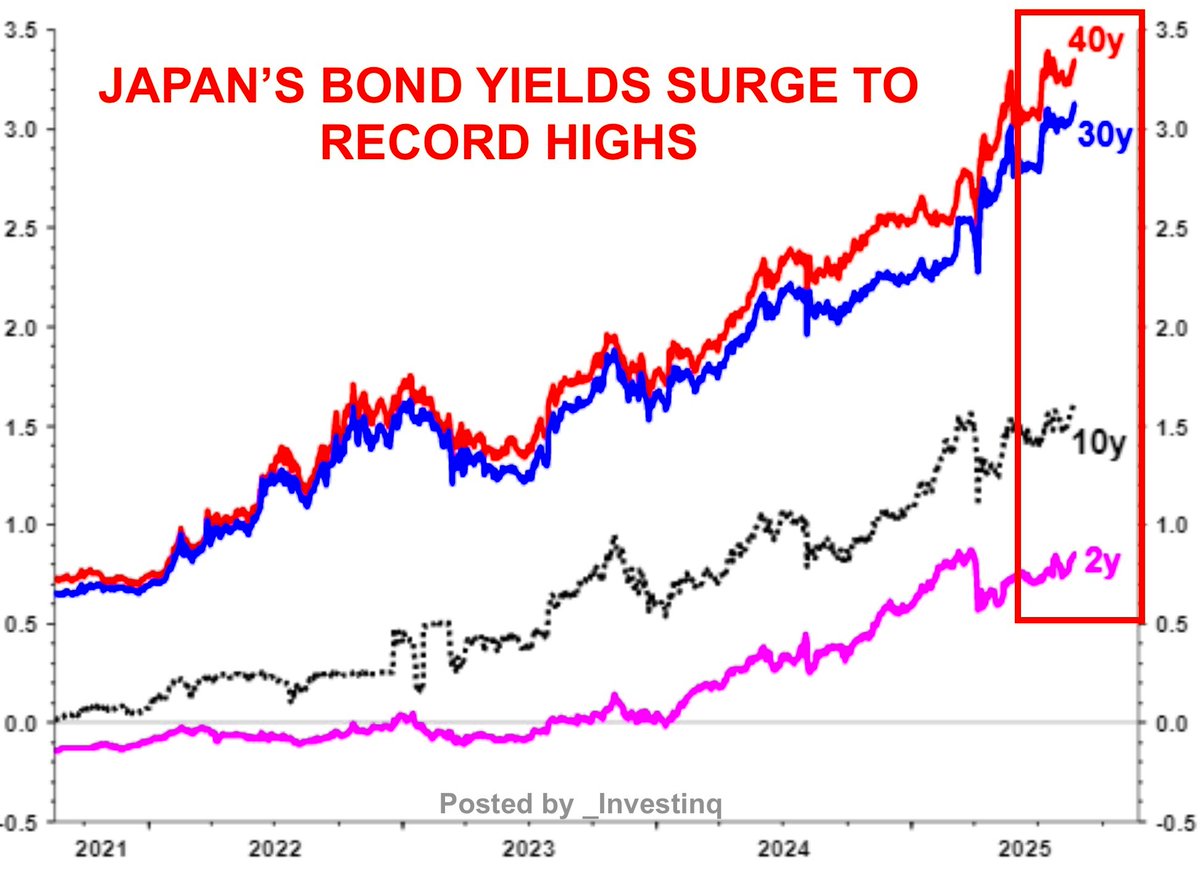

🚨 Japan’s long-term yields are going vertical.

Yields on 10Y, 20Y, 30Y, and 40Y JGBs are soaring to multi-decade highs.

This could reshape global capital flows and slam U.S. Treasuries.

(a thread)

Yields on 10Y, 20Y, 30Y, and 40Y JGBs are soaring to multi-decade highs.

This could reshape global capital flows and slam U.S. Treasuries.

(a thread)

Start with the basics. A bond is a loan. You lend money to a government or company.

In return, they pay you interest over time and give you your money back at the end.

The return you earn is called the yield.

In return, they pay you interest over time and give you your money back at the end.

The return you earn is called the yield.

Bond prices and yields move in opposite directions.

If you pay $1,000 for a bond that pays $30/year, the yield is 3%. If the bond drops to $900 but still pays $30, the yield rises to 3.33%.

When bond prices fall, yields rise.

If you pay $1,000 for a bond that pays $30/year, the yield is 3%. If the bond drops to $900 but still pays $30, the yield rises to 3.33%.

When bond prices fall, yields rise.

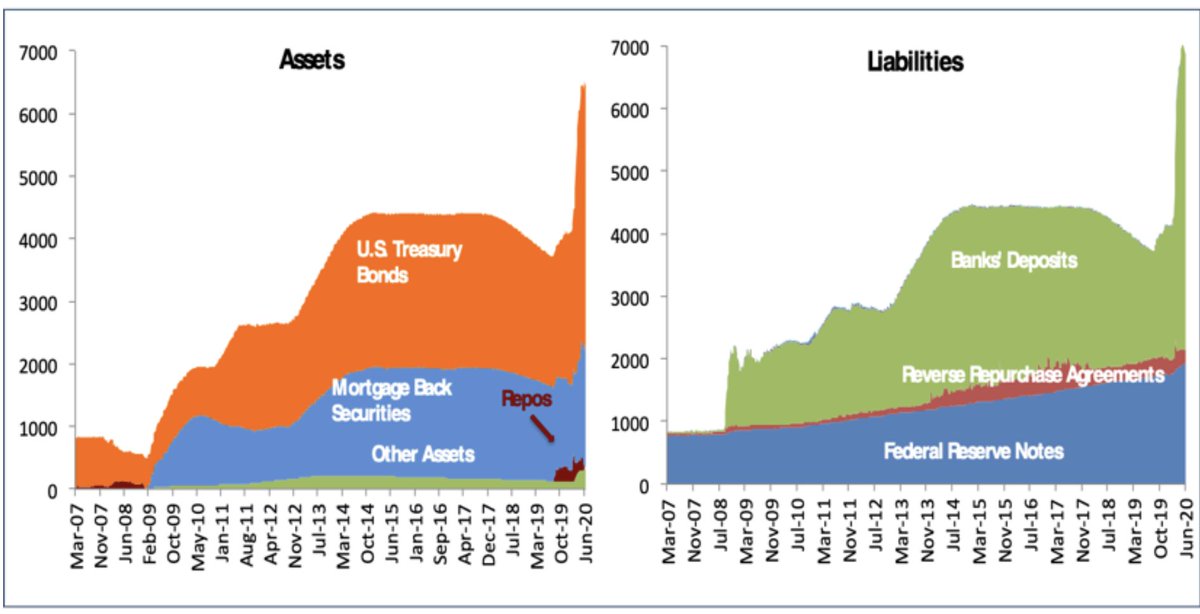

Japan’s central bank, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has kept interest rates near zero for decades to fight deflation.

It also capped long-term interest rates using a policy called Yield Curve Control (YCC).

That meant aggressively buying government bonds to suppress yields.

It also capped long-term interest rates using a policy called Yield Curve Control (YCC).

That meant aggressively buying government bonds to suppress yields.

Now inflation has returned.

The BOJ is stepping back. It’s letting long-term yields rise for the first time in years.

Yields on Japan’s 10Y, 20Y, 30Y, and even 40Y bonds are surging to levels not seen since the 1990s.

The BOJ is stepping back. It’s letting long-term yields rise for the first time in years.

Yields on Japan’s 10Y, 20Y, 30Y, and even 40Y bonds are surging to levels not seen since the 1990s.

This isn’t just a Japanese issue.

Japan is the world’s largest creditor.

Its institutions, insurers, pensions, banks hold over $3 trillion in foreign bonds. A huge portion of that is in U.S. Treasuries (1.15T).

Japan is the world’s largest creditor.

Its institutions, insurers, pensions, banks hold over $3 trillion in foreign bonds. A huge portion of that is in U.S. Treasuries (1.15T).

Why did they invest so much in U.S. debt?

Because Japanese bonds paid next to nothing. Meanwhile, U.S. Treasuries paid 3–5%.

That yield gap made it profitable to move capital out of Japan and into U.S. bonds. That’s called the carry trade.

Because Japanese bonds paid next to nothing. Meanwhile, U.S. Treasuries paid 3–5%.

That yield gap made it profitable to move capital out of Japan and into U.S. bonds. That’s called the carry trade.

Now that Japanese yields are rising, that carry trade doesn’t work like it used to.

If Japanese bonds can offer close to 2% locally with zero currency risk, then U.S. bonds even at 4%, don’t look as attractive once you factor in hedging costs.

If Japanese bonds can offer close to 2% locally with zero currency risk, then U.S. bonds even at 4%, don’t look as attractive once you factor in hedging costs.

Japanese investors hedge currency risk when they buy U.S. assets.

That hedge now costs around 2% annually.

So a 4% U.S. yield minus 2% for hedging = 2% net return barely better than what they can get at home.

That hedge now costs around 2% annually.

So a 4% U.S. yield minus 2% for hedging = 2% net return barely better than what they can get at home.

As a result, Japanese institutions are pulling back from U.S. bonds.

Some are even selling. Asahi Mutual Life, for example, announced it’s buying more domestic bonds and reducing exposure to foreign debt.

That’s a broader trend.

Some are even selling. Asahi Mutual Life, for example, announced it’s buying more domestic bonds and reducing exposure to foreign debt.

That’s a broader trend.

What happens when fewer buyers show up for U.S. debt?

Bond prices fall. Yields rise.

And that affects you, the American consumer directly.

Bond prices fall. Yields rise.

And that affects you, the American consumer directly.

When Treasury yields rise, so do interest rates across the board. That includes:

• Mortgage rates

• Auto loans

• Student loans

• Credit card interest

• Business loans

Everything becomes more expensive to borrow.

• Mortgage rates

• Auto loans

• Student loans

• Credit card interest

• Business loans

Everything becomes more expensive to borrow.

Let’s talk mortgages. Suppose you’re buying a $400,000 home:

• At 3% interest = $1,686/month

• At 7.5% interest = $2,796/month

That’s a $1,100/month difference, just from rising yields.

• At 3% interest = $1,686/month

• At 7.5% interest = $2,796/month

That’s a $1,100/month difference, just from rising yields.

That extra cost shrinks what buyers can afford.

Someone who could buy a $400K home in 2021 may now only qualify for $275K.

Home sales slow. Home prices may drop. Builders pull back. The housing market feels the pressure.

Someone who could buy a $400K home in 2021 may now only qualify for $275K.

Home sales slow. Home prices may drop. Builders pull back. The housing market feels the pressure.

It doesn’t stop there.

Car loans, credit card rates, and student loan refinancing all get more expensive.

Consumers carry more debt than ever and now they’re paying more interest on it. That hits monthly budgets.

Car loans, credit card rates, and student loan refinancing all get more expensive.

Consumers carry more debt than ever and now they’re paying more interest on it. That hits monthly budgets.

Businesses also get squeezed.

Higher borrowing costs slow expansion. Fewer new stores, warehouses, or product lines. Layoffs can follow.

And smaller businesses that rely on credit lines or loans may see profit margins evaporate.

Higher borrowing costs slow expansion. Fewer new stores, warehouses, or product lines. Layoffs can follow.

And smaller businesses that rely on credit lines or loans may see profit margins evaporate.

This is happening as the U.S. Treasury is issuing record amounts of new debt.

But foreign buyers like Japan are stepping back.

That leaves more supply and less demand pushing yields higher.

But foreign buyers like Japan are stepping back.

That leaves more supply and less demand pushing yields higher.

To entice new buyers, the U.S. has to offer higher interest.

That means even more upward pressure on mortgage and loan rates.

It also means more taxpayer dollars going to interest payments.

That means even more upward pressure on mortgage and loan rates.

It also means more taxpayer dollars going to interest payments.

The U.S. government is projected to spend over $1 trillion a year just on interest.

That’s more than the military. Soon, it’ll exceed Medicare.

Higher yields make that number worse, faster.

That’s more than the military. Soon, it’ll exceed Medicare.

Higher yields make that number worse, faster.

The stock market is also vulnerable.

Rising yields reduce the value of future profits, especially for growth and tech companies.

That’s why stocks often fall when the 10Y yield rises. Retirement accounts and 401(k)s take a hit.

Rising yields reduce the value of future profits, especially for growth and tech companies.

That’s why stocks often fall when the 10Y yield rises. Retirement accounts and 401(k)s take a hit.

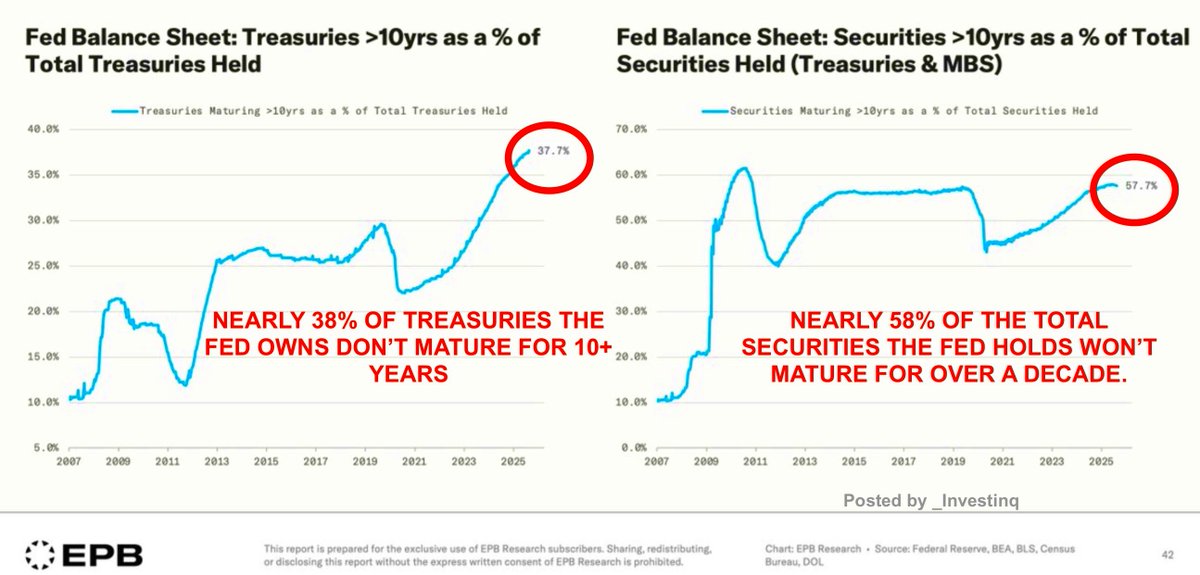

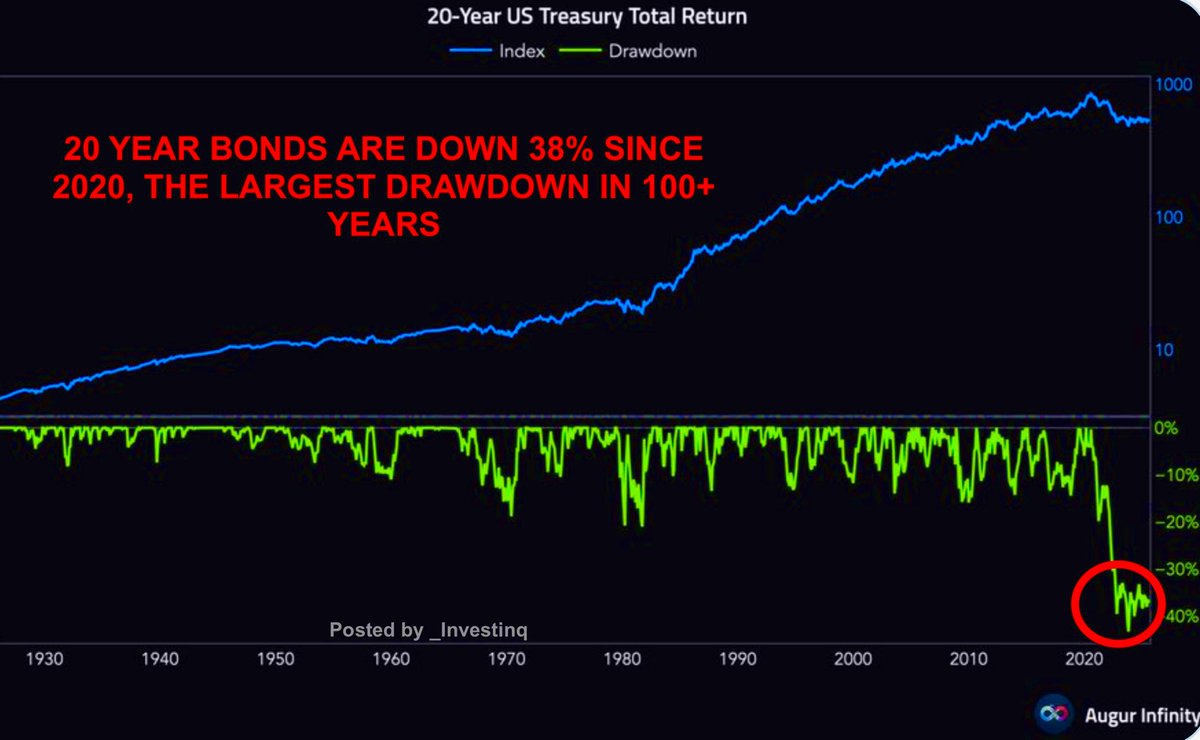

The banking system is exposed too.

Silicon Valley Bank collapsed after its long-term bond holdings tanked as yields surged.

Many banks still hold similar assets. Rising yields mean unrealized losses continue to grow.

Silicon Valley Bank collapsed after its long-term bond holdings tanked as yields surged.

Many banks still hold similar assets. Rising yields mean unrealized losses continue to grow.

This is called duration risk, the risk that bond values plunge when interest rates rise.

It’s not just a theoretical problem.

It affects financial institutions holding low-yield, long-term bonds purchased during the zero-rate era.

It’s not just a theoretical problem.

It affects financial institutions holding low-yield, long-term bonds purchased during the zero-rate era.

Even recent U.S. Treasury auctions are flashing warnings.

The government is having trouble selling long-term bonds at reasonable prices.

Demand is softening. Buyers are pushing for higher yields.

The government is having trouble selling long-term bonds at reasonable prices.

Demand is softening. Buyers are pushing for higher yields.

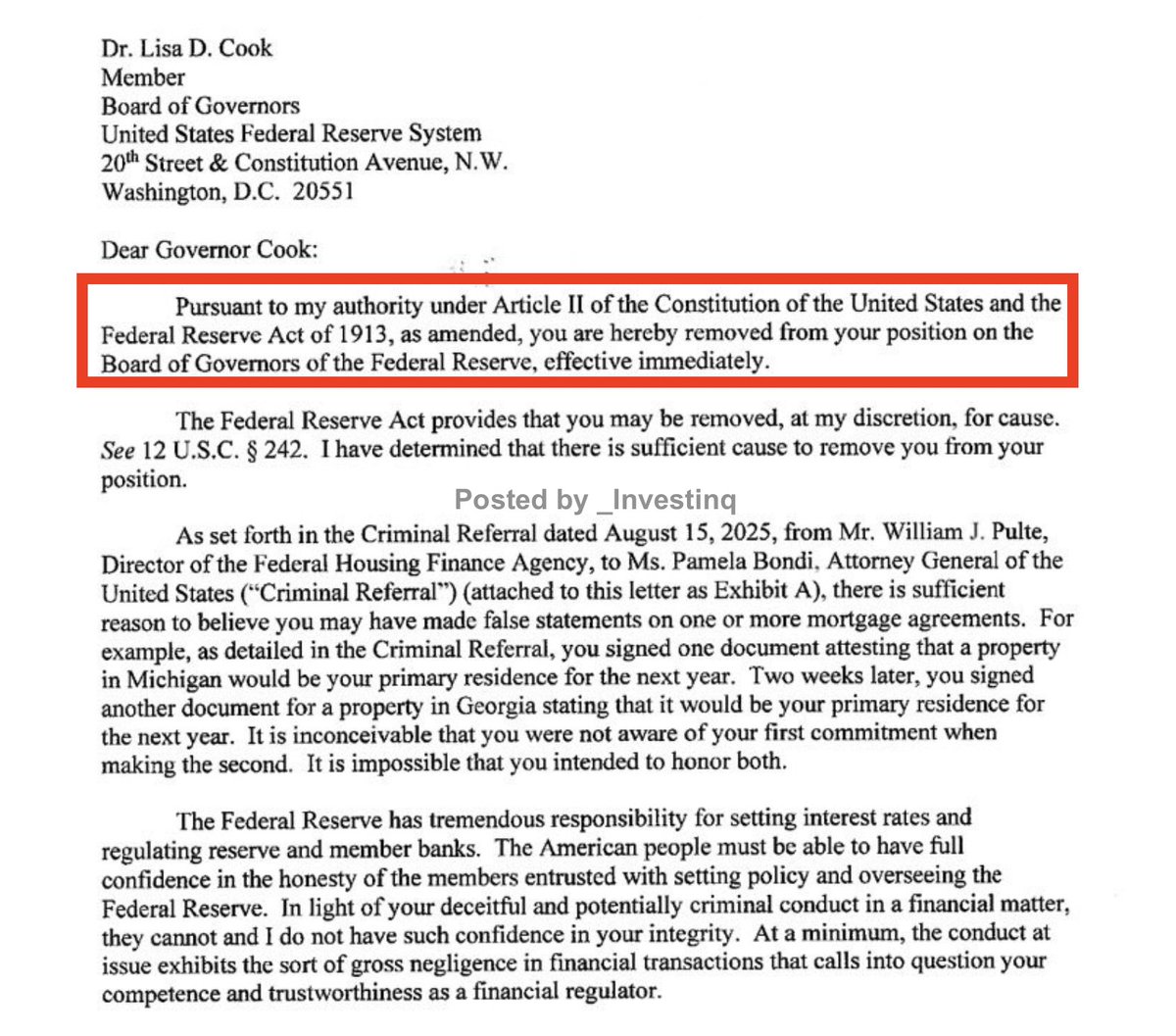

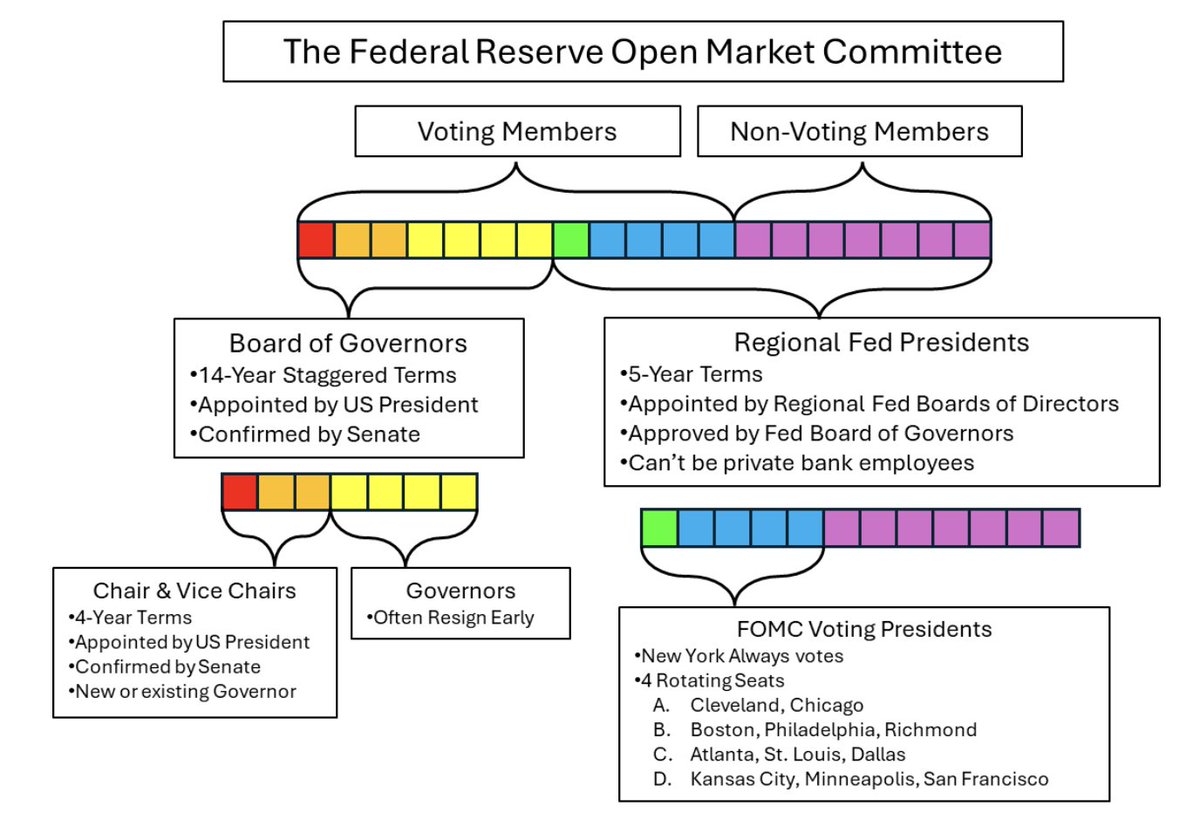

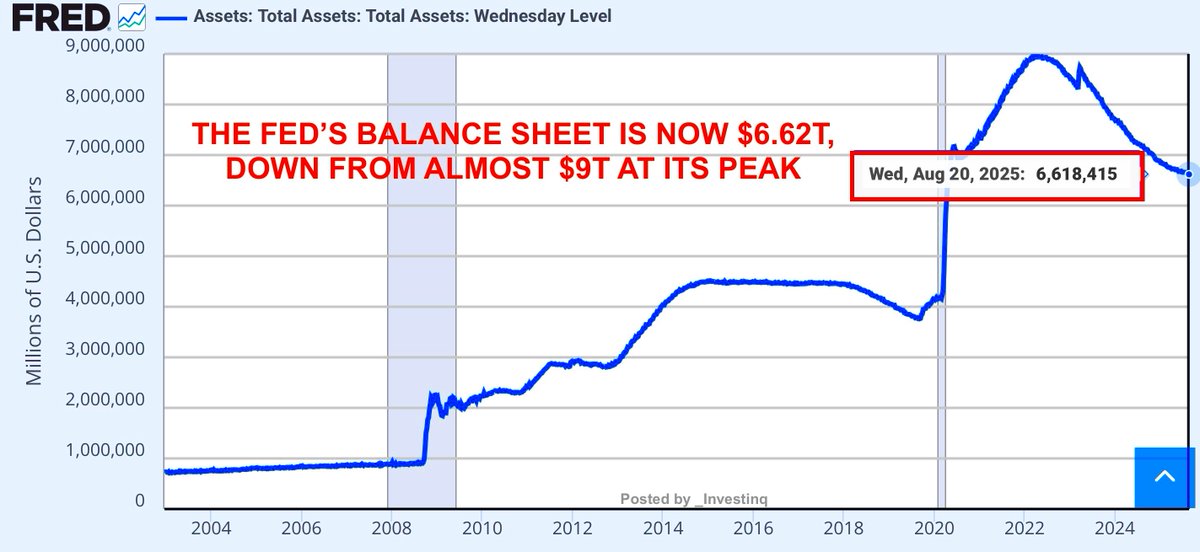

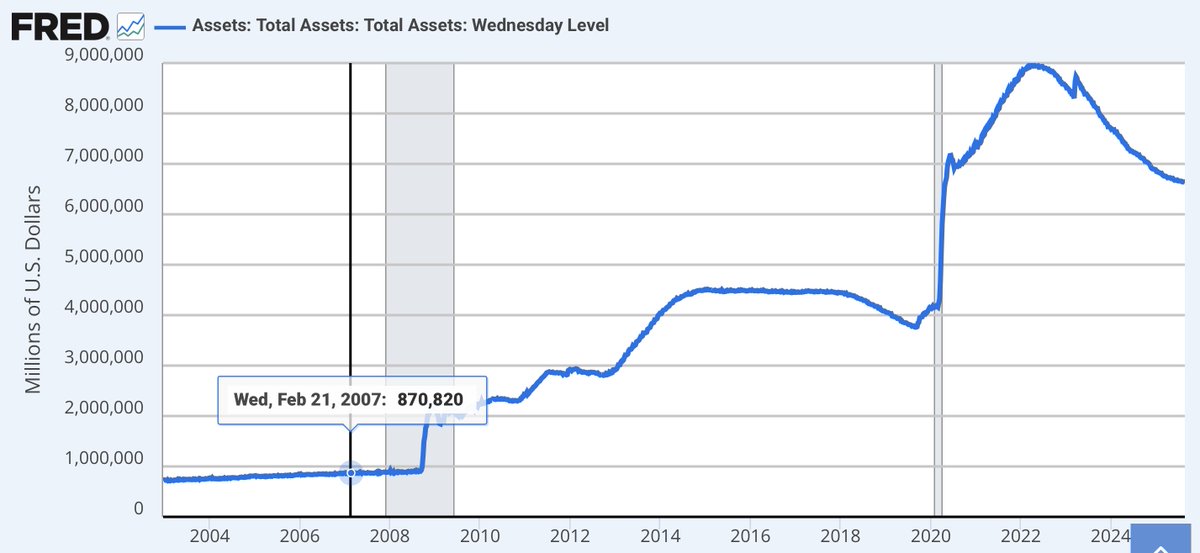

Could the Fed intervene by buying bonds again? Possibly.

But that would mean Quantitative Easing which adds money to the system and risks fueling inflation again.

It would be a last resort, and it comes with tradeoffs.

But that would mean Quantitative Easing which adds money to the system and risks fueling inflation again.

It would be a last resort, and it comes with tradeoffs.

So the chain reaction looks like this:

Japan lets yields rise → Capital stays home → U.S. Treasuries lose a major buyer → Yields rise → U.S. interest rates surge → Consumer borrowing gets more expensive → The economy slows

Japan lets yields rise → Capital stays home → U.S. Treasuries lose a major buyer → Yields rise → U.S. interest rates surge → Consumer borrowing gets more expensive → The economy slows

Unless a global recession or panic drives money back into U.S. bonds, we’re stuck with higher-for-longer yields.

That’s the new normal: more expensive borrowing, bigger government deficits, and slower consumer spending.

That’s the new normal: more expensive borrowing, bigger government deficits, and slower consumer spending.

This is not just about bond markets.

It’s about the end of the low-rate era. It’s about your mortgage, your credit card bill, your student loan, and your job.

Global monetary policy decisions are now hitting American households fast and hard

It’s about the end of the low-rate era. It’s about your mortgage, your credit card bill, your student loan, and your job.

Global monetary policy decisions are now hitting American households fast and hard

If you’re wondering why everything costs more… why housing is unaffordable… or why credit card interest is brutal, it’s not just inflation.

It’s the structural shift in how the global bond market functions and Japan is right at the center of it.

It’s the structural shift in how the global bond market functions and Japan is right at the center of it.

When the biggest creditor in the world stops buying the debt of the biggest debtor, the financial plumbing has to adjust.

And until it does, borrowing will stay expensive for consumers, businesses, and governments alike.

And until it does, borrowing will stay expensive for consumers, businesses, and governments alike.

If you found these insights valuable: Sign up for my Weekly FREE newsletter! thestockmarket.news

I hope you've found this thread helpful.

Follow me @_Investinq for more.

Like/Repost the quote below if you can:

Follow me @_Investinq for more.

Like/Repost the quote below if you can:

https://x.com/_investinq/status/1960042368872153398?s=46

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh