(1/9) Here’s how to become the best doctor you can in 2025…

Some advice (e.g. learn from your pts) is timeless but some thing are different than when Osler trained.

🧵

Some advice (e.g. learn from your pts) is timeless but some thing are different than when Osler trained.

🧵

(2/9) Learn from your patients

Learning ~= cases seen × learning extracted per case

Maximizing both is key.

Volume exposes you to varied presentations, and reflection deepens your understanding.

There’s no substitute for either. Perhaps in the coming years AI simulated presentations may assist in pattern recognition (e.g. high exposure to simulated pathology) but not quite there yet.

Learning ~= cases seen × learning extracted per case

Maximizing both is key.

Volume exposes you to varied presentations, and reflection deepens your understanding.

There’s no substitute for either. Perhaps in the coming years AI simulated presentations may assist in pattern recognition (e.g. high exposure to simulated pathology) but not quite there yet.

(3/9) Develop skills beyond knowledge

Knowledge matters, but communication, listening, problem-solving, studying, and teamwork matter more in practice.

When trainees struggle, it’s often these skills, not medical knowledge, that hold them back.

Knowledge matters, but communication, listening, problem-solving, studying, and teamwork matter more in practice.

When trainees struggle, it’s often these skills, not medical knowledge, that hold them back.

(4/9) Check your ego at the door

An ego closes you off to learning from patients, nurses, allied health, and colleagues.

The best diagnosticians I know are always primed to learn from every encounter.

An ego closes you off to learning from patients, nurses, allied health, and colleagues.

The best diagnosticians I know are always primed to learn from every encounter.

(5/9) Be curious

Especially as a trainee you’ll see approaches from your attendings you disagree with.

Don’t dismiss them—observe outcomes.

Curiosity helps you develop your own clinical style and understand the range of ways medicine can be practiced.

Especially as a trainee you’ll see approaches from your attendings you disagree with.

Don’t dismiss them—observe outcomes.

Curiosity helps you develop your own clinical style and understand the range of ways medicine can be practiced.

(6/9) Avoid the “arrival fallacy”

Matching into med school, residency, fellowship, or landing your dream job won’t magically make you happy if you aren’t already.

Find joy, meaning, and health during training—it’s the foundation for a sustainable career.

Matching into med school, residency, fellowship, or landing your dream job won’t magically make you happy if you aren’t already.

Find joy, meaning, and health during training—it’s the foundation for a sustainable career.

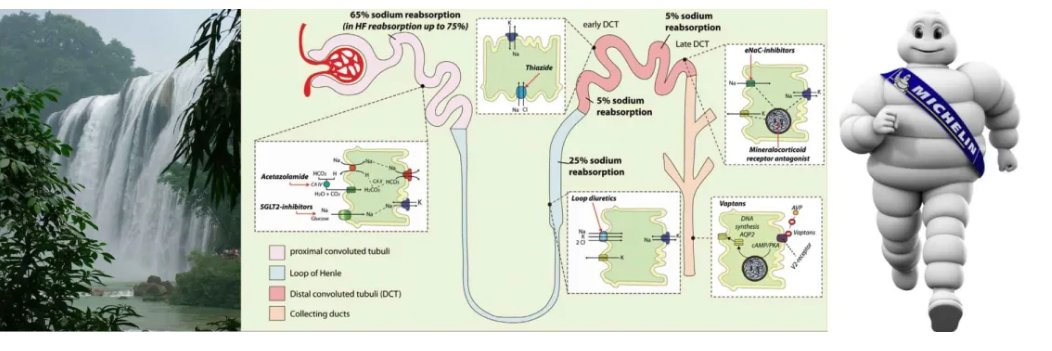

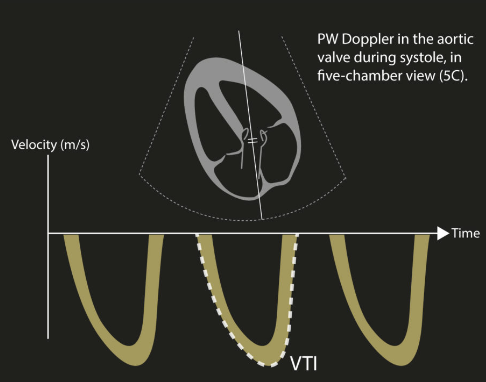

(7/9) Embrace new technology

Medicine has traditions worth keeping, and some worth breaking.

AI, software, and modern diagnostics can help us care for patients more effectively. Learn them early; they may shape your specialty.

In 2030, I predict that in almost every specialty, Human + AI will perform better than Human alone.

AI can help check our weaknesses and accentuate our strengths as humans.

Medicine has traditions worth keeping, and some worth breaking.

AI, software, and modern diagnostics can help us care for patients more effectively. Learn them early; they may shape your specialty.

In 2030, I predict that in almost every specialty, Human + AI will perform better than Human alone.

AI can help check our weaknesses and accentuate our strengths as humans.

(8/9) Don’t be a martyr

The old culture of sacrificing all aspects of your life for your career serves neither you nor your patients.

Invest in your own health and relationships.

The old culture of sacrificing all aspects of your life for your career serves neither you nor your patients.

Invest in your own health and relationships.

(9/9) Don’t be a jerk

Medicine has enough of them already.

Respect your team. Respect your patients.

That’s part of being excellent.

Medicine has enough of them already.

Respect your team. Respect your patients.

That’s part of being excellent.

Curious what others who have done this for longer than I have would say!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh