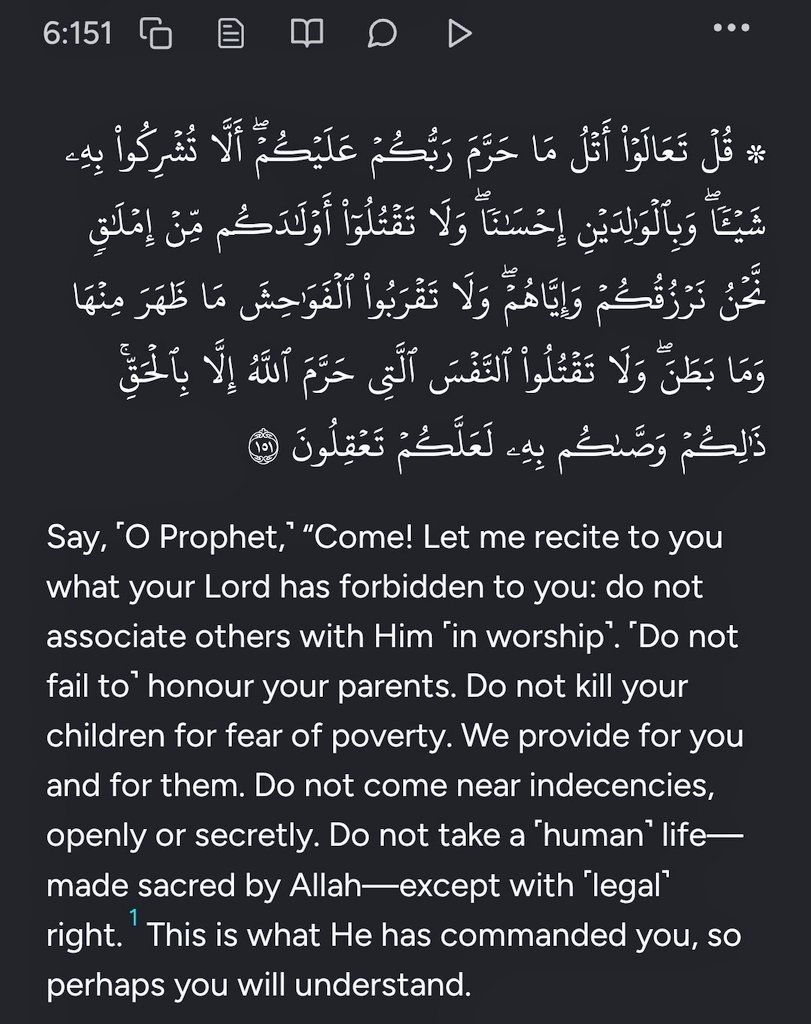

Touching the Bible in a State of Impurity

Ibn ʿĀbidīn al-Shāmī (d. 1252) writes:

“The correct position is that it is disliked to touch the Bible (in its original language whilst in a state of ritual impurity), because only some parts of these books have been altered.

Ibn ʿĀbidīn al-Shāmī (d. 1252) writes:

“The correct position is that it is disliked to touch the Bible (in its original language whilst in a state of ritual impurity), because only some parts of these books have been altered.

the majority of their contents remain unchanged, and therefore, it must be honored and protected.”

[Radd al-Muḥtār].

[Radd al-Muḥtār].

While some Christians desecrate the Qurʾān by burning it or throwing it in toilets, some of our scholars are of the view that we, as Muslims should not even touch the Bible without purification, out of reverence for the words of God that still remain within the Torah and Gospel.

Even the Jews and Christians themselves don’t revere their books to this extent.

Yet, we are portrayed by the media as intolerant savages!

Yet, we are portrayed by the media as intolerant savages!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh