🚨 The Fed just dropped new capital rules for big banks.

They dictate how much of their own money must stay locked before payouts.

It sounds technical but it affects lending, profits, and whether 2008 repeats.

(a thread)

They dictate how much of their own money must stay locked before payouts.

It sounds technical but it affects lending, profits, and whether 2008 repeats.

(a thread)

So what’s a “capital requirement”? It’s the bank’s crash helmet.

A cushion of equity money that belongs to the bank itself that can absorb losses when the economy turns ugly.

Without that helmet, taxpayers end up footing the bill when things go wrong.

A cushion of equity money that belongs to the bank itself that can absorb losses when the economy turns ugly.

Without that helmet, taxpayers end up footing the bill when things go wrong.

Capital = safety but banks dislike it.

Why? Because the more capital they’re forced to hold, the less they can lend or return to shareholders.

The Fed is constantly walking a tightrope: keep banks safe enough, but not so constrained that they choke the economy.

Why? Because the more capital they’re forced to hold, the less they can lend or return to shareholders.

The Fed is constantly walking a tightrope: keep banks safe enough, but not so constrained that they choke the economy.

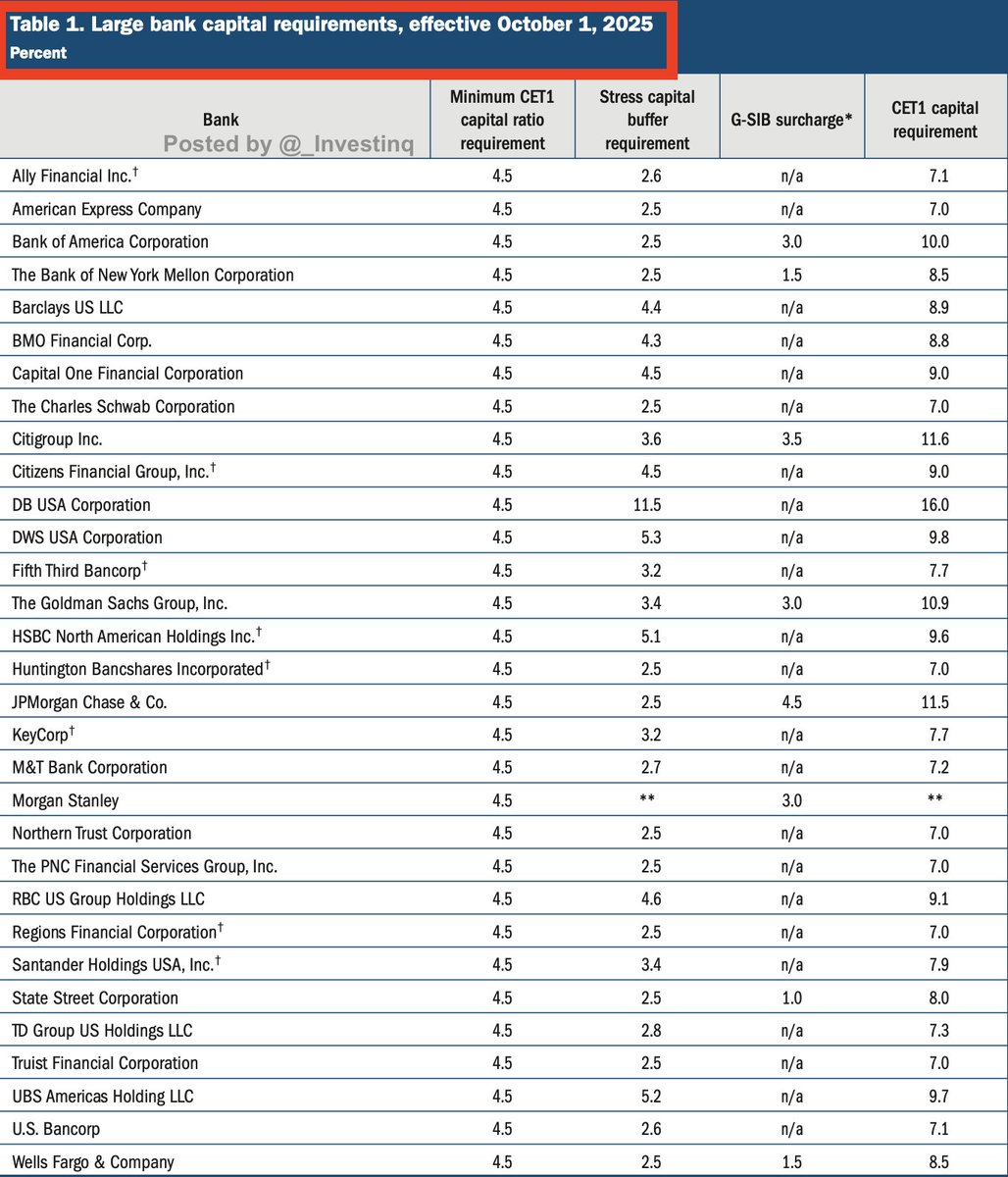

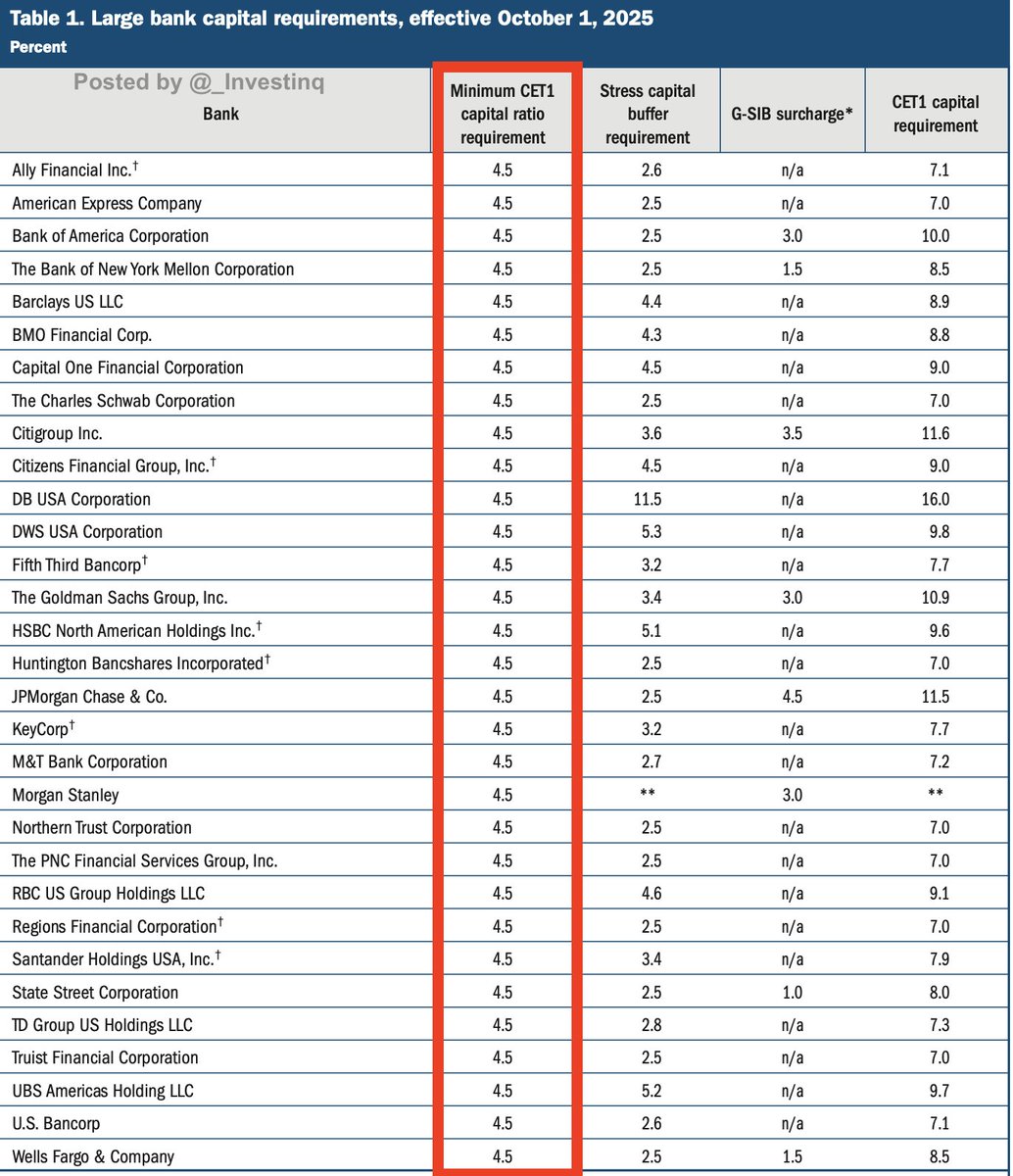

The main measure is the CET1 ratio, Common Equity Tier 1. This is pure capital (stock + retained earnings) compared to risk-weighted assets.

Think of it as a safety ratio.

The higher it is, the sturdier the bank. The lower it is, the shakier the foundation.

Think of it as a safety ratio.

The higher it is, the sturdier the bank. The lower it is, the shakier the foundation.

Every big bank starts with the same floor: 4.5% that means at least $4.50 in equity for every $100 in risky assets.

But this is just the baseline.

The real action is in the add-ons: the Stress Capital Buffer (SCB) and the G-SIB surcharge.

But this is just the baseline.

The real action is in the add-ons: the Stress Capital Buffer (SCB) and the G-SIB surcharge.

The SCB is where it gets personal. Each year, the Fed runs a “severe recession” simulation unemployment spikes, markets crash, loans default.

It calculates how much capital the bank would lose.

That drop becomes the SCB (never less than 2.5%).

It calculates how much capital the bank would lose.

That drop becomes the SCB (never less than 2.5%).

Example: If a stress test shows Citigroup would burn through 3.6% of its equity cushion in a downturn, its SCB is 3.6%.

If Goldman Sachs would burn 3.4%, its SCB is 3.4%.

Riskier balance sheets = higher SCBs. Safer banks get smaller cushions.

If Goldman Sachs would burn 3.4%, its SCB is 3.4%.

Riskier balance sheets = higher SCBs. Safer banks get smaller cushions.

Then there’s the G-SIB surcharge. G-SIB = Global Systemically Important Bank.

If you’re so big and interconnected that your failure could freeze global credit, you pay an extra capital tax.

It’s the Fed’s way of saying: “You’re too big to fail, so prove you’re too safe to fail.”

If you’re so big and interconnected that your failure could freeze global credit, you pay an extra capital tax.

It’s the Fed’s way of saying: “You’re too big to fail, so prove you’re too safe to fail.”

Add it up: Total requirement = 4.5% + SCB + G-SIB surcharge.

That’s the number banks must stay above or face automatic restrictions.

In 2025, totals range from ~7% to as high as 16%.

That’s the number banks must stay above or face automatic restrictions.

In 2025, totals range from ~7% to as high as 16%.

Why so different? Take Deutsche Bank’s U.S. arm: 16%.

The Fed’s models say it would take massive hits in a recession, especially from trading.

So the SCB alone is 11.5%.

By contrast, U.S. Bancorp’s SCB is 2.6%, leaving it at just 7.1% total.

The Fed’s models say it would take massive hits in a recession, especially from trading.

So the SCB alone is 11.5%.

By contrast, U.S. Bancorp’s SCB is 2.6%, leaving it at just 7.1% total.

What happens if a bank dips below its requirement? The rules kick in automatically.

Dividends stop. Stock buybacks stop. Executive bonuses get capped.

The goal: force banks to conserve capital before it’s too late.

Dividends stop. Stock buybacks stop. Executive bonuses get capped.

The goal: force banks to conserve capital before it’s too late.

That’s the framework but 2025 has a twist.

In April, the Fed proposed averaging stress test results over two years instead of one.

The idea: reduce year-to-year volatility in requirements.

Smooth the ride, steady the payouts.

In April, the Fed proposed averaging stress test results over two years instead of one.

The idea: reduce year-to-year volatility in requirements.

Smooth the ride, steady the payouts.

Why average? Because one year’s stress test might be unusually harsh, another unusually mild.

That can whipsaw banks. Averaging means smoother numbers.

But it also risks underestimating danger if risks are rising fast.

That can whipsaw banks. Averaging means smoother numbers.

But it also risks underestimating danger if risks are rising fast.

That’s why the Fed calls 2025 a “transition year.” October 1 rules kick in under the old system.

But if averaging is finalized, the Fed will recalc buffers using both 2024 + 2025 tests.

So banks could see a second set of numbers mid-cycle.

But if averaging is finalized, the Fed will recalc buffers using both 2024 + 2025 tests.

So banks could see a second set of numbers mid-cycle.

Morgan Stanley is a special case. It asked the Fed to reconsider its SCB.

Translation: it thinks the stress test overstated its risks.

The Fed is reviewing, and will publish MS’s final requirement by September 30.

Translation: it thinks the stress test overstated its risks.

The Fed is reviewing, and will publish MS’s final requirement by September 30.

For investors, this is huge. Lower SCBs = more room for dividends and buybacks. Higher SCBs = less room.

Bank stocks trade on these differences.

Capital rules don’t just keep banks safe. They set the ceiling for shareholder returns.

Bank stocks trade on these differences.

Capital rules don’t just keep banks safe. They set the ceiling for shareholder returns.

For the economy, the stakes are broader. More capital makes banks sturdier in a crash.

But it also means in boom times, lending is a bit tighter.

The Fed is constantly balancing: too loose and we risk crisis; too tight and we risk slow growth.

But it also means in boom times, lending is a bit tighter.

The Fed is constantly balancing: too loose and we risk crisis; too tight and we risk slow growth.

For everyday customers, the effects are subtle. You won’t see a line item called “capital buffer fee.”

But you benefit from the stability. Your bank won’t freeze your credit card, cancel your mortgage, or vanish when recessions hit.

Safety is invisible until it matters.

But you benefit from the stability. Your bank won’t freeze your credit card, cancel your mortgage, or vanish when recessions hit.

Safety is invisible until it matters.

Globally, U.S. rules set a tone.

Foreign banks operating in America like Barclays, UBS, Deutsche Bank must play by U.S. standards here.

That stops the U.S. financial system from becoming a weak link in the global chain. Everyone in the sandbox wears the same helmet.

Foreign banks operating in America like Barclays, UBS, Deutsche Bank must play by U.S. standards here.

That stops the U.S. financial system from becoming a weak link in the global chain. Everyone in the sandbox wears the same helmet.

Historically, this framework was born out of 2008. Back then, banks were thinly capitalized.

When housing collapsed, losses wiped them out. Taxpayers had to step in.

Since then, the Fed has built rules to make sure “never again” actually means never again.

When housing collapsed, losses wiped them out. Taxpayers had to step in.

Since then, the Fed has built rules to make sure “never again” actually means never again.

Europe takes a slightly different approach. Its capital rules (Basel III) are structured similarly but often require higher buffers for certain risks.

U.S. banks argue that uneven rules can make them less competitive.

This global tug-of-war never stops.

U.S. banks argue that uneven rules can make them less competitive.

This global tug-of-war never stops.

Investors react carefully to these announcements. If a bank’s SCB falls, its stock usually pops because it means more buybacks and dividends are coming.

If the SCB rises, investors brace for leaner payouts.

The rules ripple straight into Wall Street.

If the SCB rises, investors brace for leaner payouts.

The rules ripple straight into Wall Street.

And there’s a psychological angle. By smoothing stress test results, the Fed signals it believes the system is stable.

If it thought danger was imminent, it wouldn’t be trying to make rules less jumpy.

That’s an implicit vote of "confidence" in today’s economy.

If it thought danger was imminent, it wouldn’t be trying to make rules less jumpy.

That’s an implicit vote of "confidence" in today’s economy.

Still, critics worry. Smoothing results might comfort banks but could mask real risk.

If trouble is building fast, a two-year average might understate it.

In finance, stability sometimes comes at the cost of foresight.

If trouble is building fast, a two-year average might understate it.

In finance, stability sometimes comes at the cost of foresight.

The key date is October 1. That’s when the new requirements lock in.

But September 30 brings Morgan Stanley’s final ruling.

And after that, all eyes are on whether the Fed finalizes its averaging proposal. The story isn’t done.

But September 30 brings Morgan Stanley’s final ruling.

And after that, all eyes are on whether the Fed finalizes its averaging proposal. The story isn’t done.

The bottom line: Capital requirements decide how much risk banks can take, how much money they can give back to investors, how much credit they can extend, and whether taxpayers ever again rescue Wall Street.

It’s not just about ratios, it’s about resilience.

It’s not just about ratios, it’s about resilience.

If you found these insights valuable: Sign up for my FREE newsletter! thestockmarket.news

I hope you've found this thread helpful.

Follow me @_Investinq for more.

Like/Repost the quote below if you can:

Follow me @_Investinq for more.

Like/Repost the quote below if you can:

https://x.com/_investinq/status/1961537612839064017?s=46

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh