With all the Venezuela stuff going on, it’s probably as good a time as any to discuss an idea that’s been making the rounds: The idea of the US becoming a “Western Hemispheric power.” (LOOOONG thread follows)

https://twitter.com/martinskold2/status/1962600247231660324

BLUF: I think it has some merit in the abstract, but there are reasons to think it won’t shake out so neatly.

Specifically, there is a built-in geographic incentive for the US to reach east and west instead of just north and south, and being able to do the latter requires engineering a favorable Eurasian environment anyway.

I’ve noted in the past that regional hegemons in control of strategic straits and chokepoints do well.

https://x.com/martinskold2/status/1892391116684607749?s=46

If you wanted to make peace with a China-dominated world - and, with US global hegemony collapsing, we might have to - then you might think being a Western Hemispheric hegemon might have some merit.

I actually agree - except: There are a few problems.

The first is overly literal but instructive: Look at a map and see what the “Western Hemisphere” actually is.

-On paper-, the Western Hemisphere encompasses most of Britain (everywhere west of Greenwich, to put it iconically), a chunk of France, most of Spain, and all of Portugal and Ireland.

Ie, if we’re being literal (maybe we’re not, but bear with me here, because this actually will become important), to be a “Western Hemispheric hegemon” is pretty darned close to being an Atlanticist.

And there’s never been a policy maker concerned with the security of Britain or Spain that did not take cognizance of the balance of power on the European Continent.

Hold on to that thought for a second. Now consider that, again on paper, the Western Hemisphere does -not- include the US Pacific possessions Guam and Wake Island - …

… - famously on the other side of the international date line when Japan attacked them on -8- December 1941, at the same time as Pearl Harbor. en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of…

The 180 degree meridian (roughly, the date line) also cuts across the Aleutians (part of the US state of Alaska). en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/180th_mer…

I’m gilding the lily here, but let’s not forget that technically a part of -Russia- is in “our” hemisphere as well.

https://twitter.com/martinskold2/status/1791314084119396429

Also on the other side of the 180th meridian are several island chains in loose association with the US under the Compacts of Free Association. en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compact_o…

In other words, and again if we are being overly literal, to become a Western Hemispheric power only, the US would have to give up some of its actual territory and numerous informal protectorates.

But of course we are not meant to be quite that literal-minded. Presumably being a “Western Hemispheric” power means the US controls its territory but does not venture (much) outside the lines of longitude that form its boundaries.

So, Guam is in but Britain is out. Ok, but…

…there are actually other problems here.

The first is how sea powers actually maintain their sea power.

Sea powers are, of their nature, outliers: They are either on coasts (Portugal, Spain, Netherlands), islands off coasts (Britain), or on continents removed from other coasts (us). This imposes certain requirements.

Obviously, for the sea powers with geographic contiguity with land powers, not getting invaded is a critical concern - they have to avoid the other powers ganging up on them and overrunning them from the landward side.

But even sea powers that don’t have this problem have to worry about the balances of power on neighboring continents, or even not-so-neighboring ones.

I abstracted it out a little while ago: If the land powers on the big continent next door ever consolidate into a single adversary, or if they’re not contained effectively by other land powers…

https://x.com/martinskold2/status/1957183067422089295?s=46

…they can eventually use their superior industrial and economic resources gained from dominating a huge landmass to go to sea.

This is why sea powers always work with land-based coalition partners - they need a blocking force (typically the subject of a sophisticated diplomatic strategy) to prevent adversaries from consolidating.

https://x.com/martinskold2/status/1957179246129954827?s=46

To do otherwise is to -willingly- put oneself in the position Britain was in on the eve of Trafalgar.

It’s the reason Britain intervened repeatedly on the Continent in conjunction with various allies from the Spanish Succession War onward.

It’s also the reason for Britain’s ultimate downfall: It -could not- prevent the nascent US from consolidating across the Atlantic and then going global.

The catch is that the US, having stripped the European empires of their possessions after the World Wars and, by semiconscious policy, promoted their demilitarization…

…took over the role they had previously played in containing Russia, with no one to take it over afterward.

https://x.com/martinskold2/status/1886121752754782304?s=46

As I opine now and then, if you don’t want Russia becoming a European hegemon and going unchecked - which will eventually involve them using their increased and unused resources to go to sea and become a much bigger problem than they now are - …

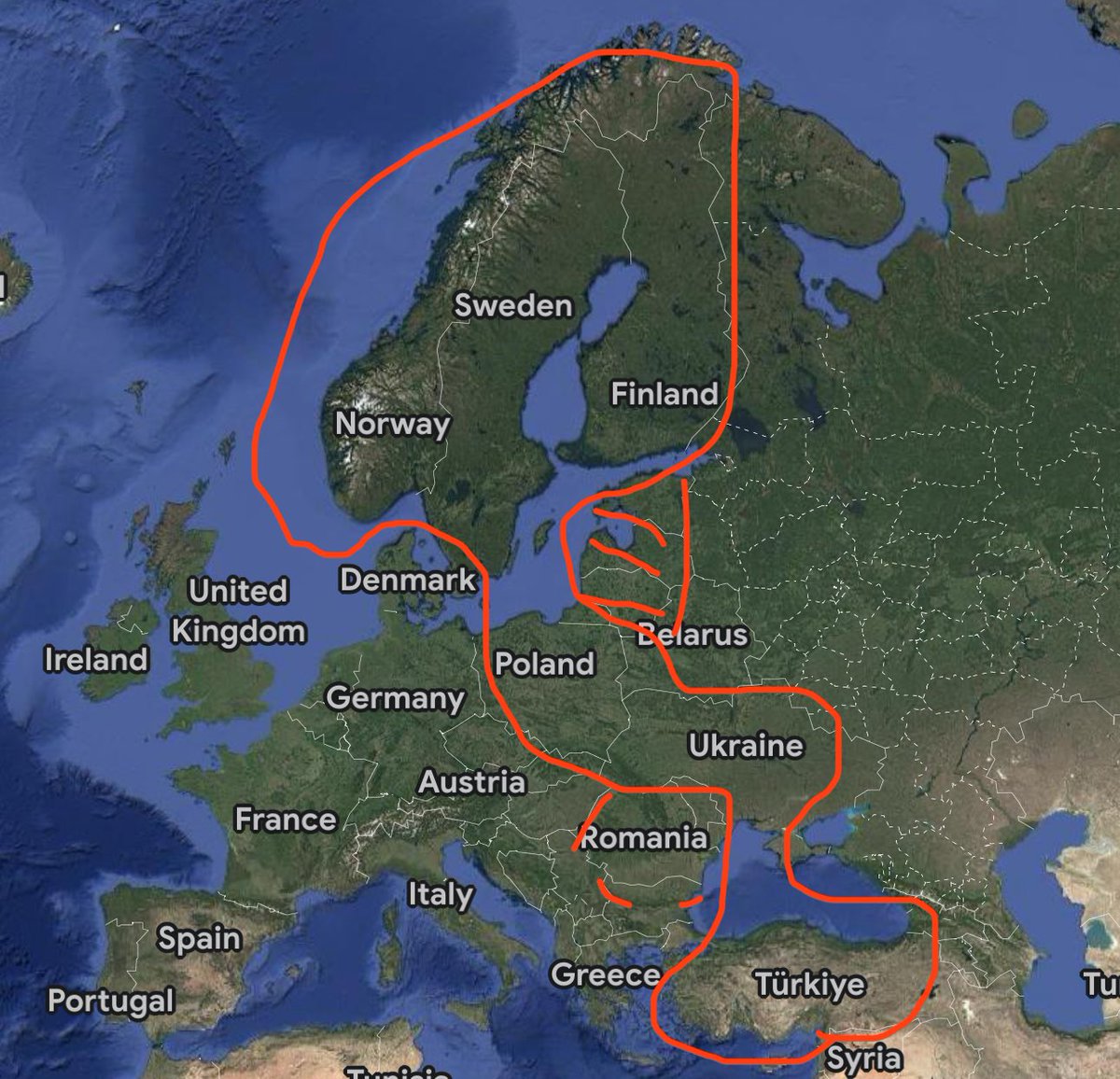

Essentially, with Western Europe down for the count and halfway to acknowledging a Russian suzerainty over Europe anyway, it looks like this:

But even if NATO is useless, even if the US can no longer afford its land commitments, even if Western Europe is unreliable, even if China is the main threat, even if people want to go home…the imperative remains the same: Someone, somehow, has to contain and balance.

I’ve talked a few times about the idea of Britain taking over in the Atlantic on the naval side (ideally while the other powers I just mentioned contain Russia on land). It won’t happen now, but it’s something to think about:

https://x.com/martinskold2/status/1957328790486438120?s=46

You could ask Turkey to help, too, but you may not want to.

https://twitter.com/martinskold2/status/1892689868578234419

(Anyway - you get the idea.)

But that’s not the half of it. Suppose we solved the Russia containment problem. It’d be nice. Now we can confine ourselves to ourselves, right?

Well…maybe not exactly.

Well…maybe not exactly.

The problem comes, again, when you take a look at a map on the other side. Remember when I said whole chunks of US territory are on the other side of the 180 degree line? Yeah. So here’s the thing: …

…China -loves- to send its fleet, and its Maritime Militia (merchant ships given specific, uh, tasks), to surround and violate outlying islands.

They’ve done it to the Senkakus, off Japan (); …en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Senkaku_I…

…and they’re doing it to the Philippines right now.

https://x.com/minhdr18/status/1961750331823685879?s=46

If we look weak enough (or, God help us, if we -are-), they’ll do it to us.

As I’ve noted now and then, they also take advantage of island separatist movements, including one very close to home.

https://x.com/martinskold2/status/1958330758835343607?s=46

Islands, of course, are prone to separatism because they’re, well, islands - they’re already somewhat separate; they inevitably have people who aren’t happy with being conjoined…or how that happened. ()en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lili%CA%B…

If we want to avoid this headache, not least given the yawning disparity in US vs. Chinese shipbuilding, we need to keep -China- bottled up and busy.

Which leads to the Taiwan problem.

Yes, there are a million problems with the Taiwanese being unable and unwilling to defend themselves…

Yes, there are a million problems with the Taiwanese being unable and unwilling to defend themselves…

https://twitter.com/martinskold2/status/1517565401265278976

…and it might be rational to write them off, but the consequences have to be considered: …

…China isn’t going to stop there, and it’s a lot easier to contain them at the First Island Chain, in narrow straits with Japan and Taiwan helping, than at the Second, a much larger area we’d be covering pretty much by our lonesome.

https://x.com/martinskold2/status/1839751947034996800?s=46

There are different ways to manage these issues, but the point is: As long as the US faces Europe but has possessions across the international date line, it’s going to have to manage both ends - there’s nothing “hemispheric” about it.

Which brings me to the third element of the problem: South America.

Yes, there are a million reasons why South America is important, but two points need emphasizing: Not all of it is as close by as you think, and the US was only ever exclusively focused on it when the US was weak (on the one hand) but growing (on the other).

As to the first: As I’ve been noting, even Venezuela is a long way from the US - it’s actually at the limit of a CONUS-based combat aircraft’s radius.

https://twitter.com/martinskold2/status/1962580162916032959

The eastern tip of South America is in fact so close to Europe and Africa that it’s been remarked that it might have been discovered by Portuguese mariners operating out of Cape Verde had Columbus not made his leap into the unknown instead.

(Felipe Fernandez-Armesto makes this point in his Columbus biography, iirc: )a.co/d/hWmGoku

It’s simply not the case that Latin America represents a zone that is uniformly or inherently “close-in” for US influence or reach except in a very relative sense.

Now, it actually is arguable (at least) that in the 19C, during the US’ supposed “isolationist” phase, when the US actually had ships patrolling the Falklands and ultimately intervened in Britain’s dispute with Venezuela over Guyana (plus ça change…)…

…that US policy actually faced south during this time, instead of toward either ocean. In theory, this could happen again.

But not automatically.

But not automatically.

In the first place, this ignores the above - the US possessions, which it must defend, lest it call its entire social compact into question, that lie far further out, as well as the problem of adversaries going unchecked.

But even setting that aside: -The last time the US had a LatAm focus, it was a rising, not a declining, power, Latin America was comparatively weak, and Eurasian powers were distracted and/or down for the count- (!).

We would have to engineer that situation if we wanted it to apply again - it’s not automatic. Which takes us back to the Eurasian containment problem.

And European powers -still- interfered in the Americas - they fought over Mexico ()…en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maximilia…

…tried to secure its loyalty ()…en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zimmerman…

…sold arms to both sides of our Civil War trying to break us up ()…militarytrader.com/militaria-coll…

…contemplated blockades of our coasts ()…history.navy.mil/research/libra…

…and had extensive territorial possessions that they relinquished but grudgingly ().en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guyana–Ve…

It’s noteworthy that the gap between the Spanish-American War and US entry into WWI is less than 20 years, and the gap between the Spanish-American War and US involvement in the Pacific was effectively instantaneous, since the US inherited Spain’s possessions…

…including some of the ones we were just talking about. history.com/articles/how-t…

Ie, the -instant- the US was even able to become a “Western Hemispheric” power, it became a trans-oceanic one as well, ipso facto.

It’s not an accident that amid triumphal announcements of the US adopting its new “Western Hemispheric” role (“We’re gonna buy Greenland! And we’re gonna retake the Canal! And we’re gonna take on the cartels! And - and - and…!”)…

…and Russia ( ) are holding naval exercises off our coasts…

https://x.com/thenewarea51/status/1791207801059946653?s=46

…aiding and abetting an illegal immigration wave ()…chathamhouse.org/2022/06/chinas…

…inciting domestic pro-Palestine riots ()…voanews.com/amp/china-s-st…

…and arming those same cartels while facilitating fentanyl shipments ( - to pick among many).strategycentral.io/post/the-carte…

We should be so lucky as to have them tied up on their continent, as was the case with European powers in the 19C. We aren’t.

If we want that, we’re going to have to -engineer- an opposition closer to them - somehow.

But that means playing - with money, arms, and diplomacy, if not with forces (which we don’t have) across the oceans, exactly what “Western Hemispheric power” proponents do not want.

FÍN

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh