1. Stabilized cap rate (yield):

Since we focus on value add, the entry cap doesn’t matter, as long as we can service our debt

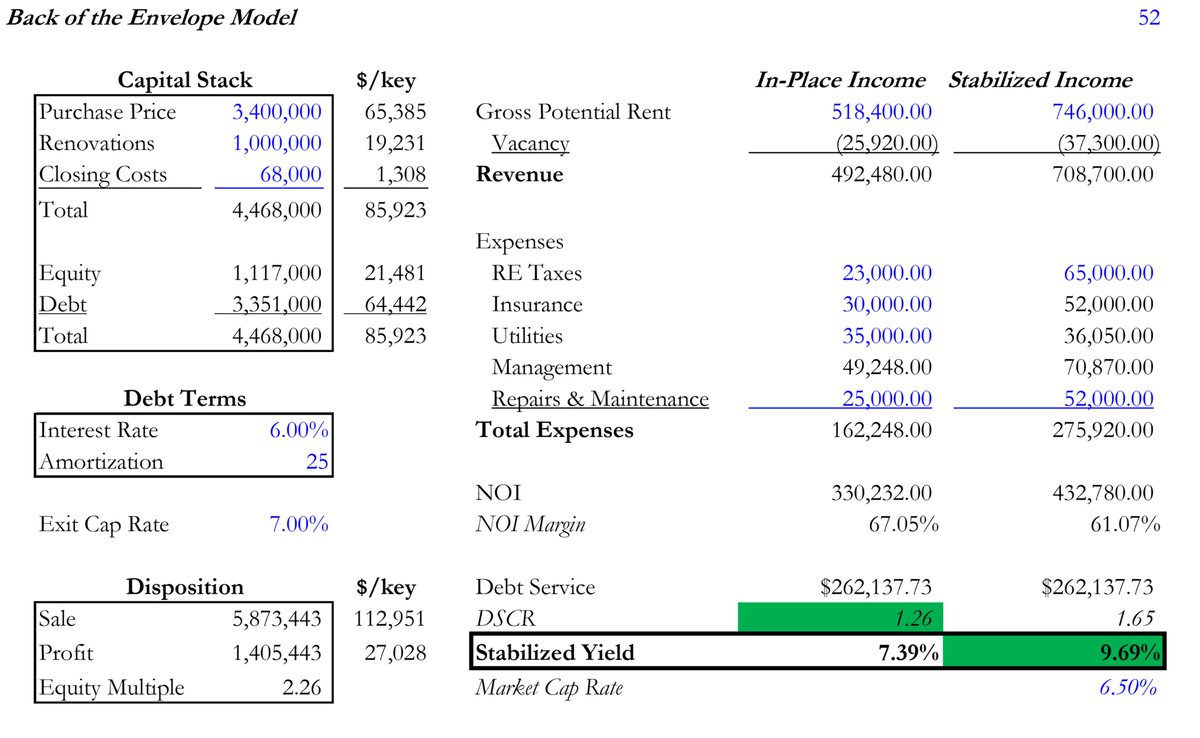

The stabilized yield matters because it shows the intrinsic cash flow of the deal

The stabilized yield is the stabilized (post-renovation) NOI divided by all the costs in the deal

Very simple calculation (see below for an example) but very important

We typically need to get to at least a 150 bp spread between the stabilized yield and the market cap rate for a deal to pencil (ex if market cap rate is 5%, need a minimum 6.5% stabilized yield)

For example, buy for an in-place 4 cap, increase revenue to get to a 6.5, sell for a 5 cap. If you buy for $10MM with an NOI of $400k, put in $2MM in renovations and bump the NOI to $780k, you stabilize at a 6.5 yield ($780k/$12MM)

Property is then worth $15.6MM ($780k/5% market cap), for a profit of $3.6MM

Speed matters as well (quicker the better for IRR)

Stabilized yield is a more important metric than IRR because it displays the intrinsic value of the cash flow

Whereas IRR is a bet on the state of the capital markets (debt financing available) at sale as well as cap rates at sale, which basically makes it a total guess

Since we focus on value add, the entry cap doesn’t matter, as long as we can service our debt

The stabilized yield matters because it shows the intrinsic cash flow of the deal

The stabilized yield is the stabilized (post-renovation) NOI divided by all the costs in the deal

Very simple calculation (see below for an example) but very important

We typically need to get to at least a 150 bp spread between the stabilized yield and the market cap rate for a deal to pencil (ex if market cap rate is 5%, need a minimum 6.5% stabilized yield)

For example, buy for an in-place 4 cap, increase revenue to get to a 6.5, sell for a 5 cap. If you buy for $10MM with an NOI of $400k, put in $2MM in renovations and bump the NOI to $780k, you stabilize at a 6.5 yield ($780k/$12MM)

Property is then worth $15.6MM ($780k/5% market cap), for a profit of $3.6MM

Speed matters as well (quicker the better for IRR)

Stabilized yield is a more important metric than IRR because it displays the intrinsic value of the cash flow

Whereas IRR is a bet on the state of the capital markets (debt financing available) at sale as well as cap rates at sale, which basically makes it a total guess

2. Basis (you can show us any IRR you want and we’ll toss the deal if the basis is bad)

What does this mean? It means that you want to look at comps and make sure that in any deal you buy, you’re paying less than the market average

For example, multifamily is valued per unit

So if you take 10 comps and the average price is $100k/unit, you want to be buying for well under that number

Otherwise (barring the real estate being markedly better), you’re not getting a good deal, you’re simply paying “market”

Furthermore that means, in order to sell for a profit, the next buyer will actually have to pay you “above market”. Which is a dangerous bet to make - you’re essentially betting on a “greater fool”, which brings us to the next metric

What does this mean? It means that you want to look at comps and make sure that in any deal you buy, you’re paying less than the market average

For example, multifamily is valued per unit

So if you take 10 comps and the average price is $100k/unit, you want to be buying for well under that number

Otherwise (barring the real estate being markedly better), you’re not getting a good deal, you’re simply paying “market”

Furthermore that means, in order to sell for a profit, the next buyer will actually have to pay you “above market”. Which is a dangerous bet to make - you’re essentially betting on a “greater fool”, which brings us to the next metric

3. Exit basis: This is heavily tied to #2 - you don’t want to invest in deals where the projected exit basis is significantly above current the market basis

For example, if the current market basis is $100k/unit, you’d want to buy for $60k/unit and pencil a sale at $80k/unit

That gives you a lot of breathing room and allows the next buyer to make money as well

Know this is all easier said than done, but this is how disciplined underwriting works

For example, if the current market basis is $100k/unit, you’d want to buy for $60k/unit and pencil a sale at $80k/unit

That gives you a lot of breathing room and allows the next buyer to make money as well

Know this is all easier said than done, but this is how disciplined underwriting works

4. Unlevered vs levered returns (IRR):

This is just a gut check to make sure that our leverage isn’t out of control

Basically you want to check to make sure that the levered returns aren’t drastically different than the levered returns

Otherwise you don’t have a good deal, you just have a lot of leverage

This is just a gut check to make sure that our leverage isn’t out of control

Basically you want to check to make sure that the levered returns aren’t drastically different than the levered returns

Otherwise you don’t have a good deal, you just have a lot of leverage

5. Equity Multiple:

Only check this to make sure that they’ll be enough profit for the deal to be worth it (no point in 20% IRR and 1.2x EM - waste of time)

Only check this to make sure that they’ll be enough profit for the deal to be worth it (no point in 20% IRR and 1.2x EM - waste of time)

6. Cash-on-cash:

A lot of amateur investors emphasize cash on cash returns but it’s a far less important metric than stabilized yield because it’s reliant on the debt capital markets at any point in time, which isn’t intrinsic to the property

So it’s “downstream” of the yield

It’s also less important for quick flips (which is predominantly what PE firms do) because a lot of units turn over during the stabilization process, which results in choppier revenue for those years

We essentially ignore this metric and expect cashflow to be very low during the hold period (unless we’re working with a specific LP who wants to optimize for cashflow)

Often even have to make (planned) capital calls and have earn-outs built into debt covenants to inject more capital for a value-add aspect of a deal (ex. tenant buildout)

A lot of amateur investors emphasize cash on cash returns but it’s a far less important metric than stabilized yield because it’s reliant on the debt capital markets at any point in time, which isn’t intrinsic to the property

So it’s “downstream” of the yield

It’s also less important for quick flips (which is predominantly what PE firms do) because a lot of units turn over during the stabilization process, which results in choppier revenue for those years

We essentially ignore this metric and expect cashflow to be very low during the hold period (unless we’re working with a specific LP who wants to optimize for cashflow)

Often even have to make (planned) capital calls and have earn-outs built into debt covenants to inject more capital for a value-add aspect of a deal (ex. tenant buildout)

7. Components of NOI:

Then you look at the cash flow itself

What are the components of the rev? What are the components of the expenses? What risks could cause major fluctuations in either one? Are you willing to accept these risks?

How do these risks compare to other deals?

You want to make sure you going into each deal with eyes wide open

There’re risks to every deal (that’s unavoidable) but you want to make sure the deal makes sense on a risk-adjusted basis

And you want to make sure there are downside mitigants and multiple exit options

Lastly, this isn’t really a metric, but the most important part of our analysis is whether the deal is actually viable on a risk-adjusted basis and whether the property is actually good real estate

Investing in only *great* RE has allowed us to outperform

If you want to make real money in real estate but don’t know where to start,

Apply in the next post for the Acquisitions Bootcamp where I’ll work 1-on-1 with you to find you a profitable deal

If you don’t have a deal within 2 months, I will work for free until you do

Then you look at the cash flow itself

What are the components of the rev? What are the components of the expenses? What risks could cause major fluctuations in either one? Are you willing to accept these risks?

How do these risks compare to other deals?

You want to make sure you going into each deal with eyes wide open

There’re risks to every deal (that’s unavoidable) but you want to make sure the deal makes sense on a risk-adjusted basis

And you want to make sure there are downside mitigants and multiple exit options

Lastly, this isn’t really a metric, but the most important part of our analysis is whether the deal is actually viable on a risk-adjusted basis and whether the property is actually good real estate

Investing in only *great* RE has allowed us to outperform

If you want to make real money in real estate but don’t know where to start,

Apply in the next post for the Acquisitions Bootcamp where I’ll work 1-on-1 with you to find you a profitable deal

If you don’t have a deal within 2 months, I will work for free until you do

Acquisitions Bootcamp is an 8-week program where you work 1-on-1 with me to craft an investment strategy to fit your skillset, resources & goals - & then find you a deal to fit that strategy

Limited spots available

Apply below

calendly.com/realestategod/…

Limited spots available

Apply below

calendly.com/realestategod/…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh