I run a real estate private equity firm. 300+ clients helped, $25MM+ in deal volume with the Acquisitions Bootcamp: https://t.co/dWVeG9RZF3

28 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

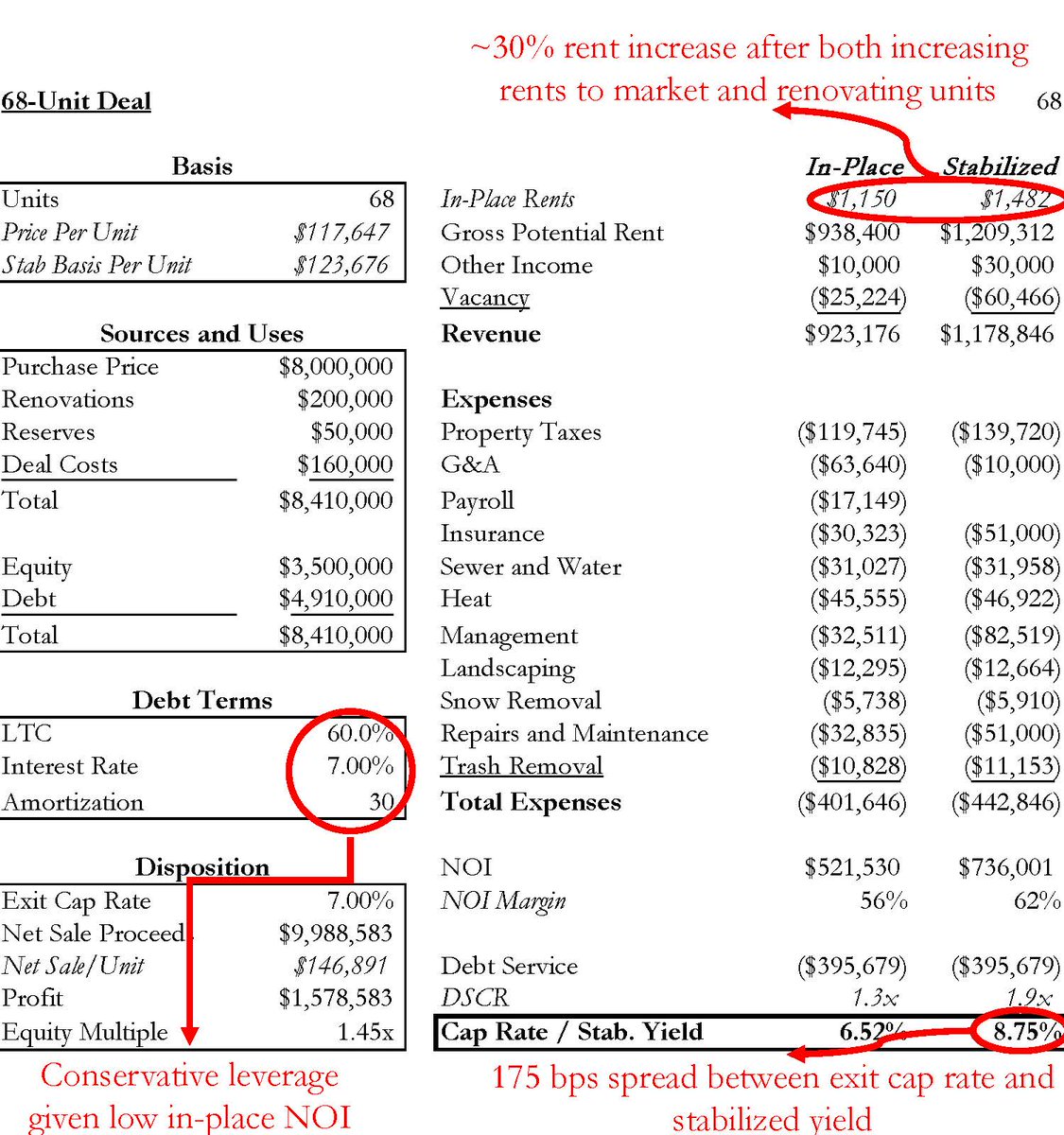

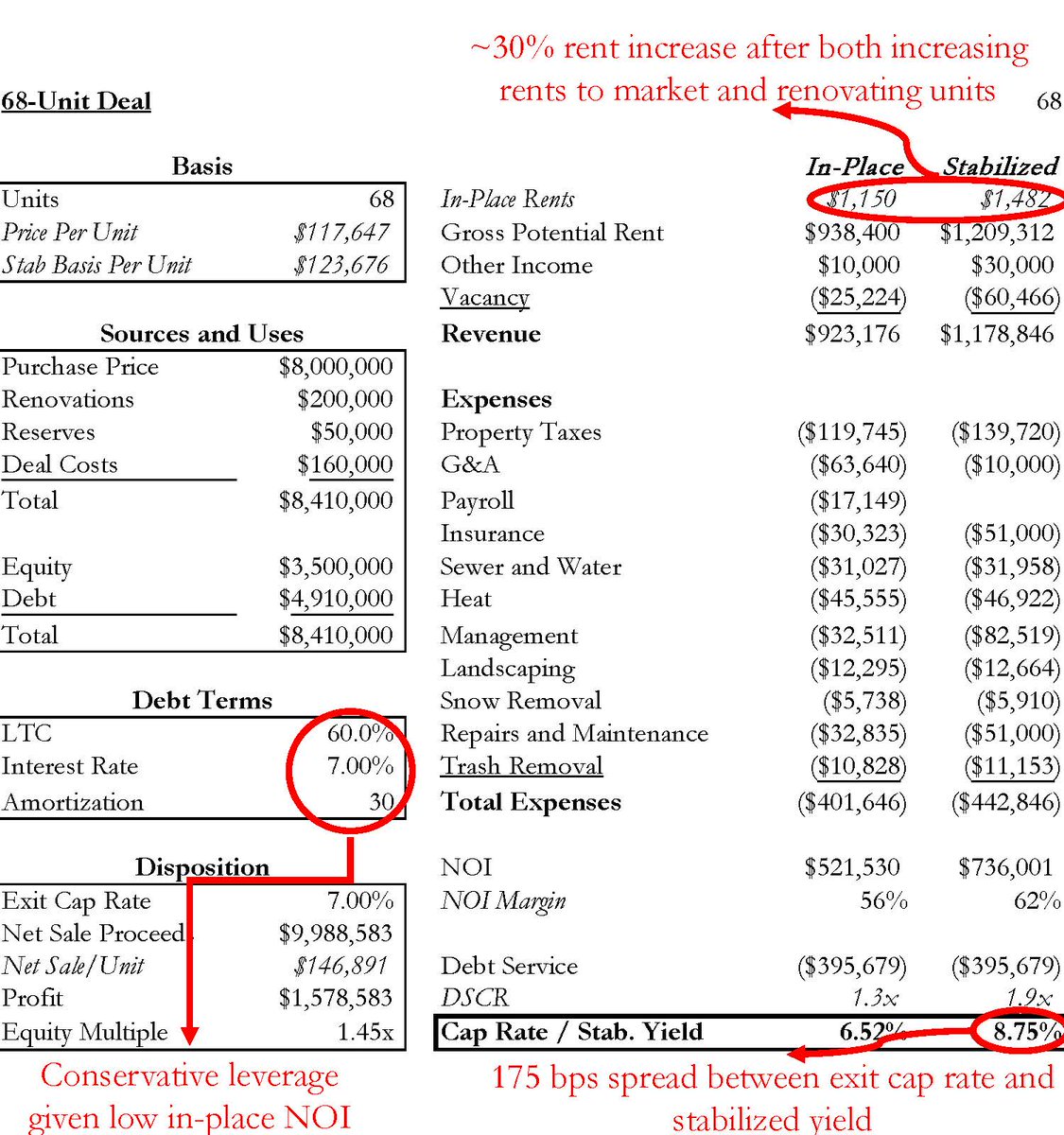

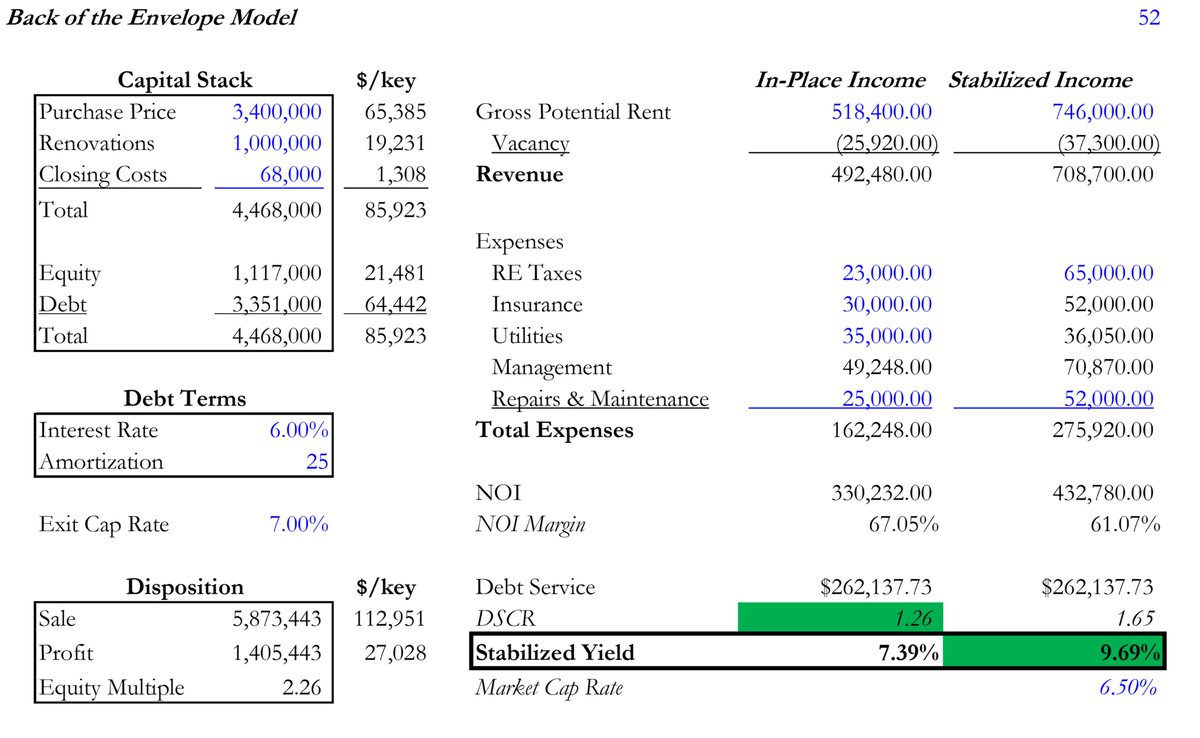

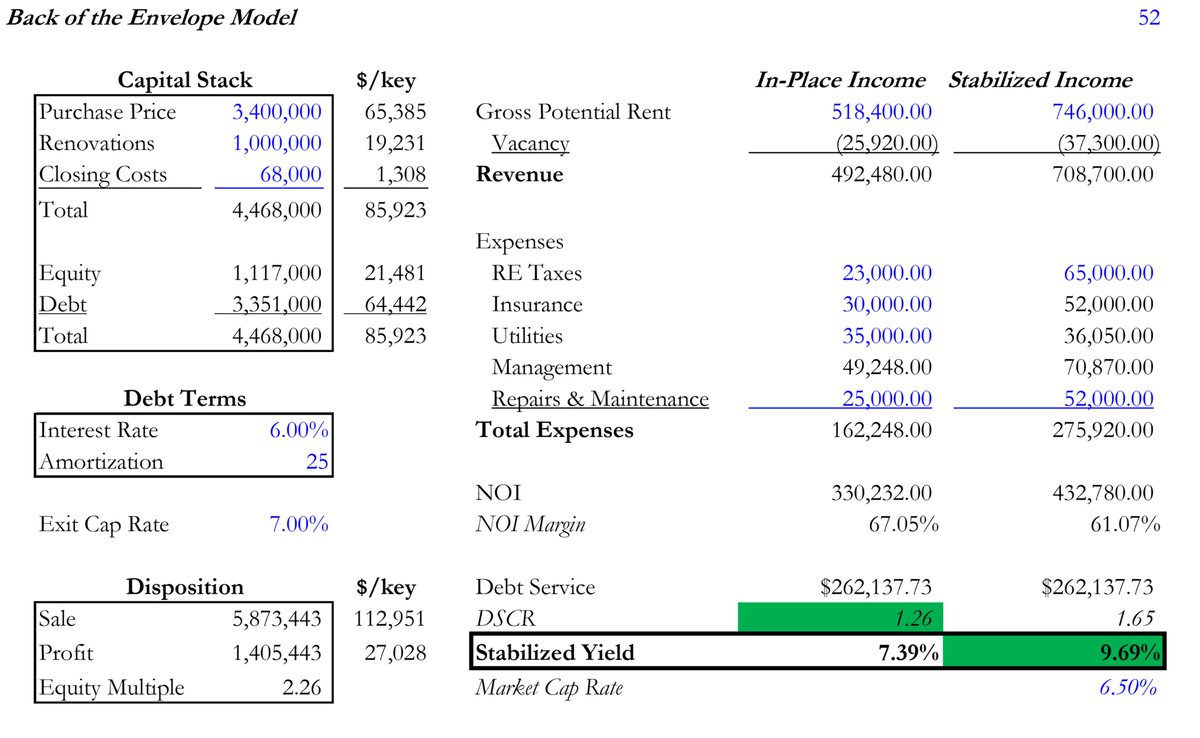

// Deal 1 //

// Deal 1 //

1. Stabilized cap rate (yield):

1. Stabilized cap rate (yield):

// Deal 1 //

// Deal 1 //

1. Stabilized cap rate (yield):

1. Stabilized cap rate (yield):

// Deal 1 //

// Deal 1 //

1. The deal wasn’t listed on loopnet (came straight from a not-that-well-known broker). Means 90%+ of the market didn’t even see it

1. The deal wasn’t listed on loopnet (came straight from a not-that-well-known broker). Means 90%+ of the market didn’t even see it

1. Stabilized cap rate (yield):

1. Stabilized cap rate (yield):

// Deal 1 //

// Deal 1 //