Picture the world in 2050, just 25 years from now. Will factories in Bangladesh produce goods as efficiently as those in Japan? Will India's economy finally rival that of the United States? These aren't just abstract questions, they're about the economic futures of billions.🧵👇

For decades, economists held what seemed like ironclad logic, poor countries should grow faster than rich ones. If you're starting from almost nothing, you have enormous room to grow, right? You can copy technologies, learn from mistakes, and leapfrog entire stages of development.

This "convergence hypothesis" suggested developing nations would naturally catch up to developed ones. It painted a picture of a world where global inequality was just a temporary phase. It was a beautiful, hopeful theory. Unfortunately, reality has been far more complicated.

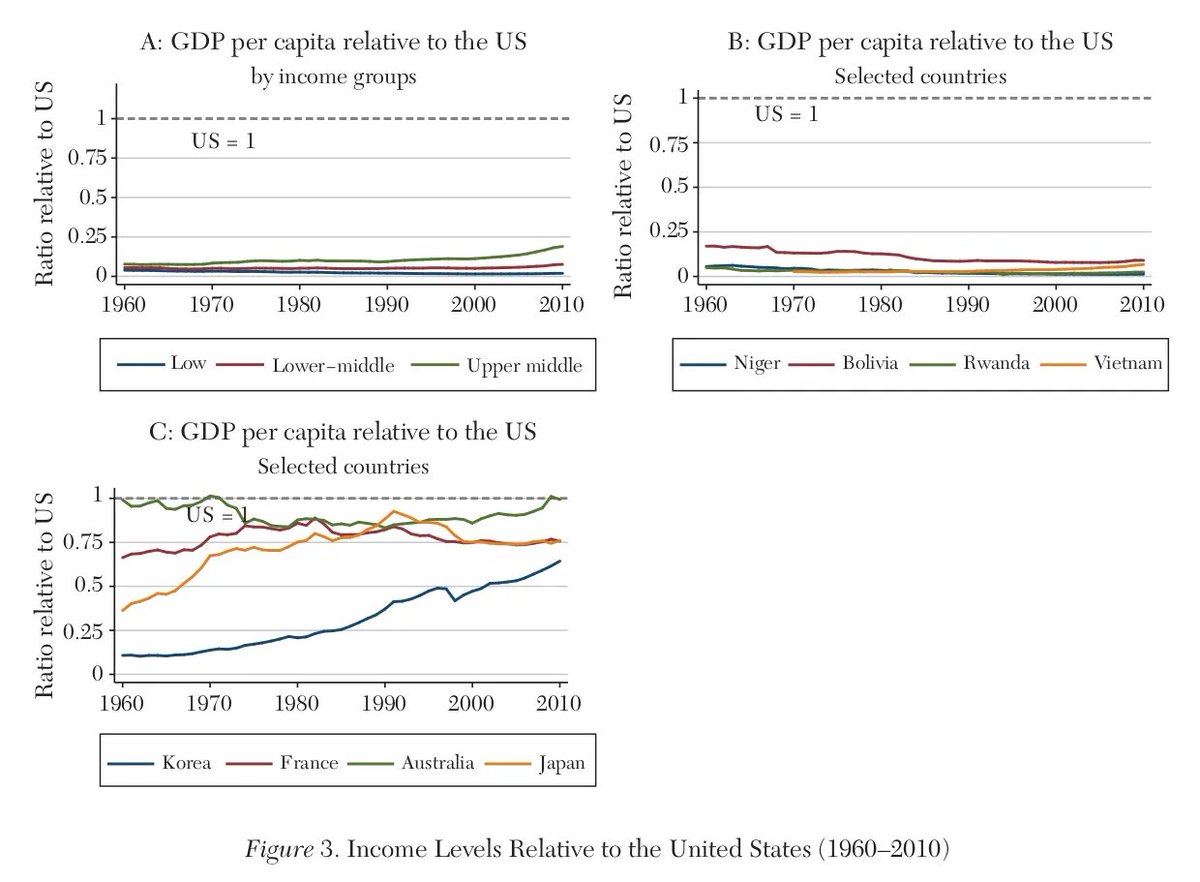

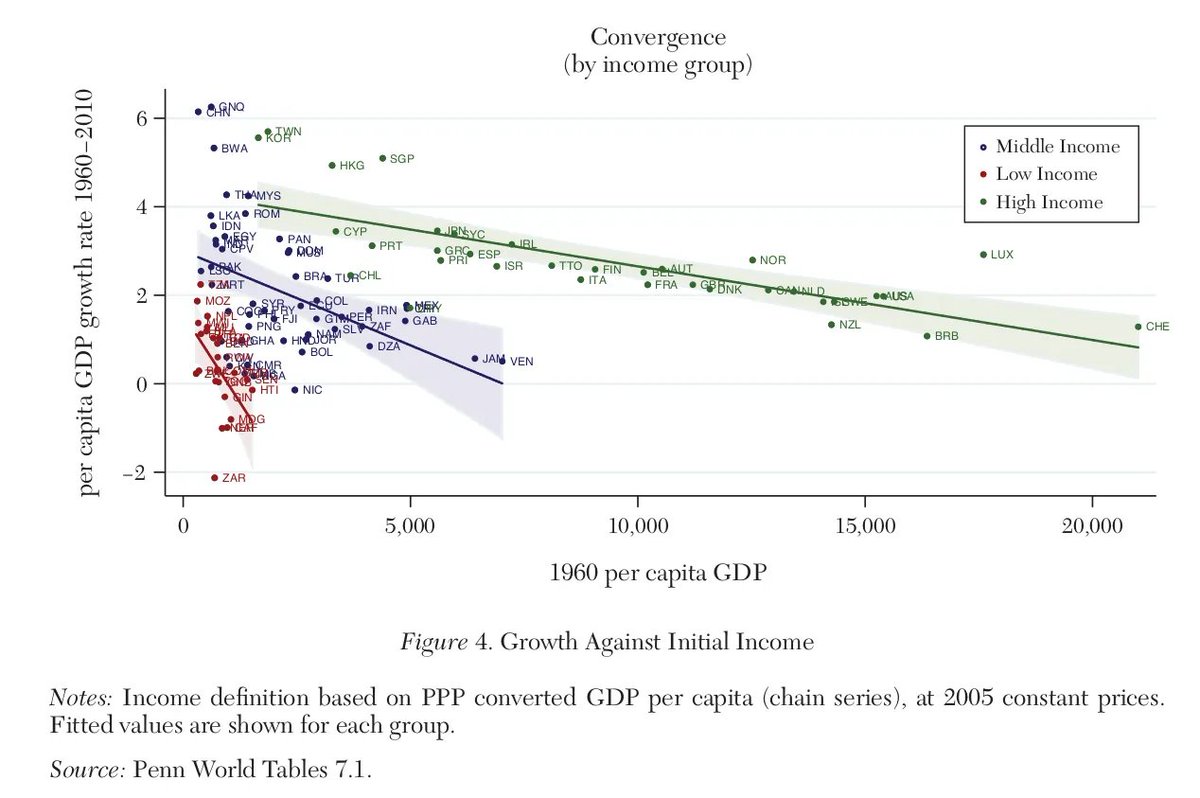

When researchers Paul Johnson and Chris Papageorgiou analyzed data from 182 countries, they found little evidence that national economies are catching up to their richest peers. High-income countries tended to grow faster than middle-income countries.

Even worse, low-income countries actually experienced negative growth rates during the 1980s and 1990s. "The consensus that we find in the literature leads us to believe that poor countries, unless something changes, are destined to stay poor," one researcher noted.

Instead of poor countries catching up, we've seen "convergence clubs," countries that started with similar income levels in 1960 and still had similar income levels in 2010. The convergence hypothesis did not seem to be playing out in practice.

But there's a catch. While countries as a whole aren't converging, something fascinating is happening within specific industries. New research shows that manufacturing industries exhibit strong convergence over time.

Researchers analyzed 99 countries across 22 manufacturing industries over four decades. Manufacturing industries that start far behind their global leaders can grow dramatically faster, sometimes seeing an extra boost that's absolutely massive compared to average growth rates.

This convergence pattern holds across virtually every manufacturing industry studied. But some sectors catch up much faster than others. If you're making cigarettes, you'll gradually close the gap. But if you're building cars or smartphones, you can catch up almost five times faster.

Why such huge variation? It was observed that industries that rely more on human capital, skilled educated workers, are driving convergence. Meanwhile, dependence on physical capital like machines and equipment doesn't seem to matter as much.

Think about the difference between a cigarette factory and a smartphone factory. The cigarette factory mostly needs machines and basic labor. The smartphone factory needs engineers who understand complex circuits, technicians who can troubleshoot sophisticated assembly lines.

Industries requiring highly educated workforces, like making chemicals, advanced machinery, and communication equipment, catch up with global leaders much faster than industries that rely mainly on manual labor, like textiles or food processing.

When you're trying to adopt cutting-edge manufacturing techniques, you need workers who can understand, implement, and improve upon those techniques. A highly educated workforce can absorb and adapt new technologies much faster, read technical manuals, troubleshoot problems.

But human capital alone isn't the defining factor. Industries that need massive, expensive equipment, think steel mills or oil refineries, can catch up rapidly, but only if the country has a sophisticated financial system.

In countries with weak banks and limited capital markets, these industries actually fall further behind global leaders over time. They simply can't get the huge loans needed to buy modern equipment. But in countries with well-developed banking systems, these same industries catch up rapidly.

The path of development shapes convergence too. As economies shift from agriculture to industrial and service sectors, they rely more on human capital. Since human capital-intensive activities converge faster, this structural transformation drives overall economic convergence.

Look at Vietnam, among the world's poorest countries in the 1960s, but by the 1990s one of the fastest-growing economies globally. How? By moving millions of workers from rice paddies into factories making textiles, electronics, and other manufactured goods.

China's transformation is perhaps the most dramatic example. In the 1960s, China actually had negative economic growth. But by focusing on manufacturing and moving workers from agriculture into factories, it became the world's fastest-growing major economy.

Here's a crucial insight, economic growth in developing countries isn't smooth and predictable. It's "episodic," characterized by sudden bursts of rapid growth followed by sharp declines. A country's growth rate in one decade is almost completely useless for predicting the next.

Poor countries can catch up, but only if they get the fundamentals right AND sustain them over time. Countries that invest in their people while building modern financial systems and fostering the right kinds of industries, those will close the gap with wealthy nations.

We cover this and one more interesting story in today's edition of The Daily Brief. Watch on YouTube, read on Substack, or listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

All links here:thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/how-power-pr…

All links here:thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/how-power-pr…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh