Trump just asked the Supreme Court to take up his tariff appeal.

He’s betting an emergency law lets him tax the world.

Now the justices must decide if that power belongs to the president or to Congress.

(a thread)

He’s betting an emergency law lets him tax the world.

Now the justices must decide if that power belongs to the president or to Congress.

(a thread)

The law at the center is the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), passed in 1977.

It gives presidents broad authority during a “national emergency” involving foreign threats.

But IEEPA’s text only says “regulate importation.” It never explicitly says “tariffs” or “duties.”

It gives presidents broad authority during a “national emergency” involving foreign threats.

But IEEPA’s text only says “regulate importation.” It never explicitly says “tariffs” or “duties.”

Historically, IEEPA was used for targeted sanctions financial penalties against hostile actors.

Presidents froze Iranian assets after the hostage crisis or blocked North Korean firms from the U.S. system.

But until Trump, no president ever tried to use it for sweeping tariffs.

Presidents froze Iranian assets after the hostage crisis or blocked North Korean firms from the U.S. system.

But until Trump, no president ever tried to use it for sweeping tariffs.

Trump declared a national emergency over trade deficits (when a country imports more than it exports) and “unfair” reciprocity in trade.

Then he slapped tariffs on nearly all U.S. trading partners.

That was new. No president had ever used IEEPA for global tariffs instead of targeted sanctions.

Then he slapped tariffs on nearly all U.S. trading partners.

That was new. No president had ever used IEEPA for global tariffs instead of targeted sanctions.

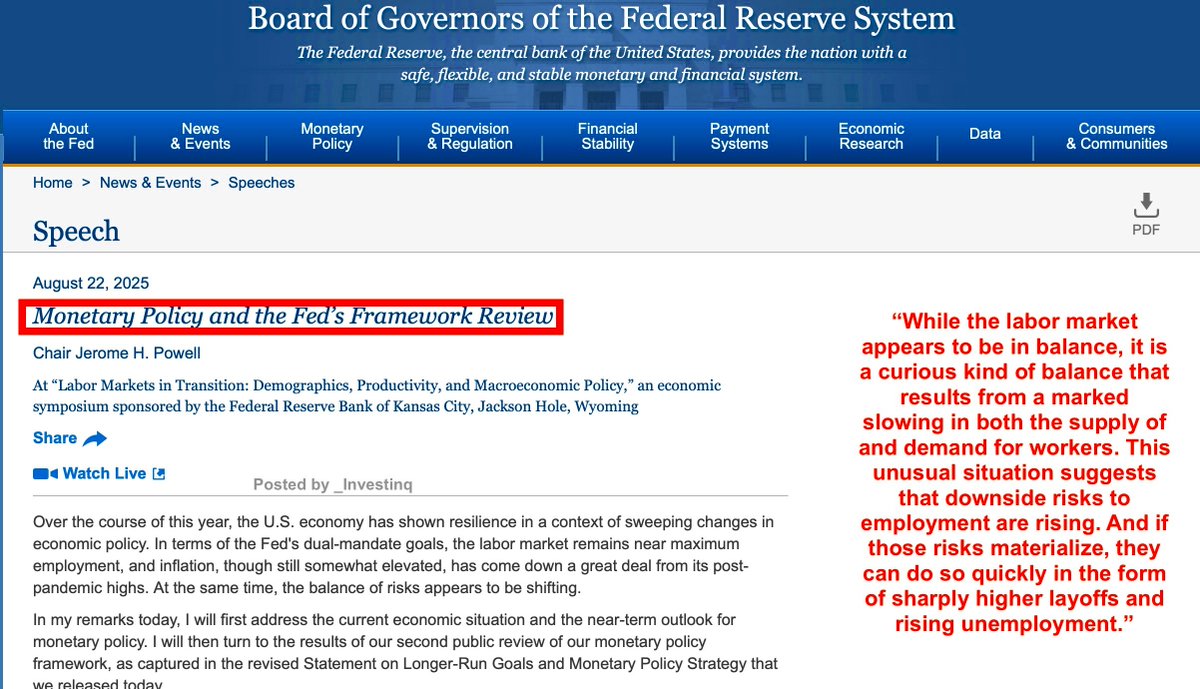

In August 2025, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals ruled 7–4 against Trump.

The judges said tariffs are taxes.

And the Constitution says Congress not the president controls the power to tax but the court paused its ruling until October 14, 2025, keeping tariffs alive during appeal.

The judges said tariffs are taxes.

And the Constitution says Congress not the president controls the power to tax but the court paused its ruling until October 14, 2025, keeping tariffs alive during appeal.

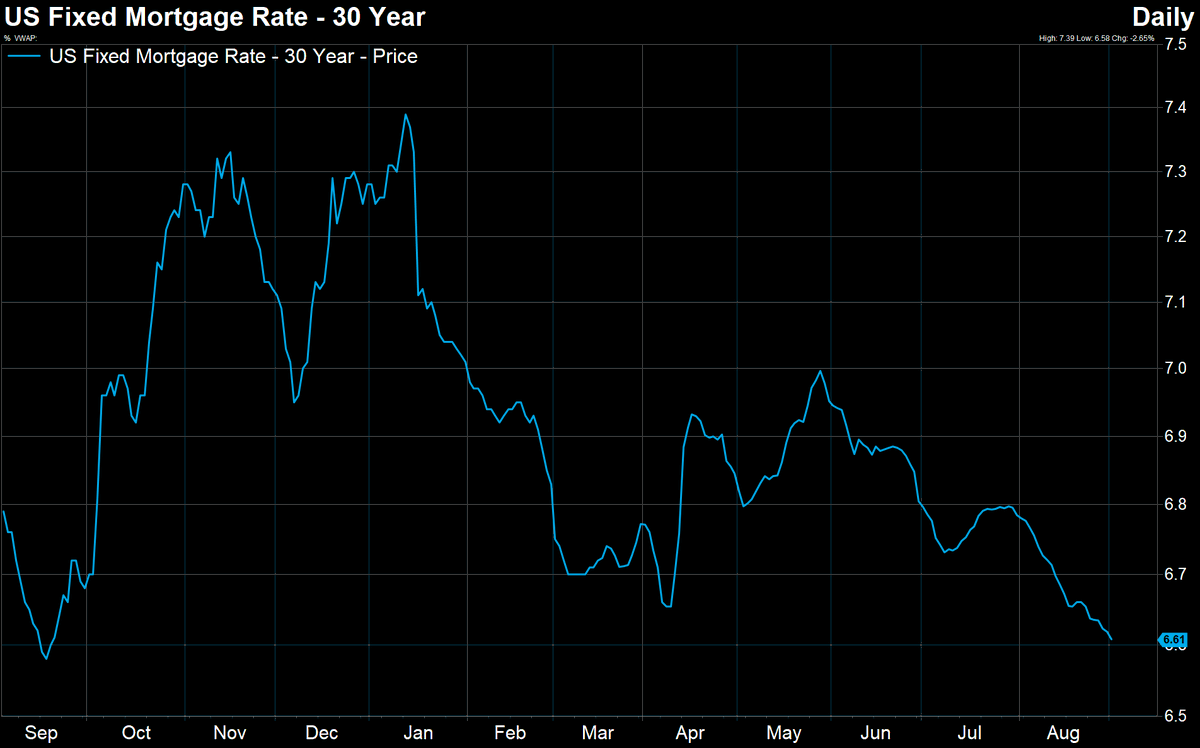

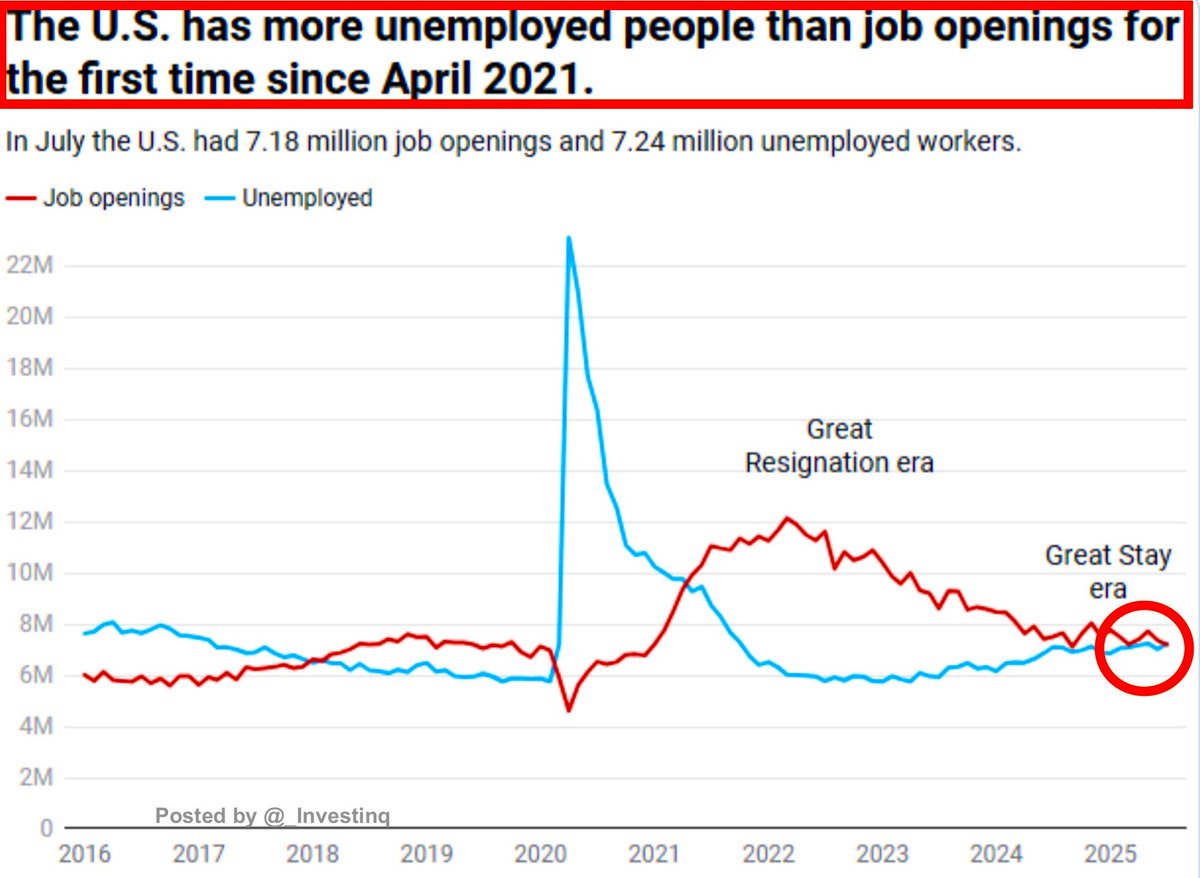

That pause matters. Businesses still pay duties at the port.

Consumers still face higher prices because importers often pass costs along.

And Trump still has bargaining power in trade talks but the fate of the tariffs is now in the Supreme Court’s hands.

Consumers still face higher prices because importers often pass costs along.

And Trump still has bargaining power in trade talks but the fate of the tariffs is now in the Supreme Court’s hands.

Normally, presidents can impose tariffs only through laws where Congress gave explicit permission.

• Section 232: tariffs if imports threaten national security.

• Section 301: tariffs to punish unfair trade practices.

• Section 201: tariffs to shield industries from import surges.

• Section 232: tariffs if imports threaten national security.

• Section 301: tariffs to punish unfair trade practices.

• Section 201: tariffs to shield industries from import surges.

These laws all mention tariffs directly. They require procedures like investigations, reports, and evidence.

IEEPA doesn’t. It just says “regulate importation.”

Trump argues that’s broad enough to mean tariffs. Critics say “regulate” is not the same as “tax.”

IEEPA doesn’t. It just says “regulate importation.”

Trump argues that’s broad enough to mean tariffs. Critics say “regulate” is not the same as “tax.”

Trump points to history.

In 1971, President Nixon imposed a 10% import surcharge (a temporary tariff) using IEEPA’s predecessor law, the Trading With the Enemy Act (TWEA).

Courts later upheld it in the Yoshida case. This is Trump’s precedent.

In 1971, President Nixon imposed a 10% import surcharge (a temporary tariff) using IEEPA’s predecessor law, the Trading With the Enemy Act (TWEA).

Courts later upheld it in the Yoshida case. This is Trump’s precedent.

But Yoshida was different. Nixon’s surcharge lasted just five months.

It was tied to a genuine monetary crisis foreign countries were dumping dollars, threatening collapse of the fixed exchange rate system.

Trump’s tariffs? Broad, indefinite, and based on chronic issues like trade deficits.

It was tied to a genuine monetary crisis foreign countries were dumping dollars, threatening collapse of the fixed exchange rate system.

Trump’s tariffs? Broad, indefinite, and based on chronic issues like trade deficits.

Congress learned from Nixon. They worried presidents had too much unchecked power under TWEA.

So in 1977, they created IEEPA. It required annual renewal of emergencies, reporting to Congress, and limits on peacetime use.

The intent was to rein in, not expand, tariff powers.

So in 1977, they created IEEPA. It required annual renewal of emergencies, reporting to Congress, and limits on peacetime use.

The intent was to rein in, not expand, tariff powers.

Now comes the Major Questions Doctrine.

This principle says if the government takes an action of huge economic or political importance, Congress must have clearly authorized it.

Massive tariffs on most imports qualify. A vague word like “regulate” doesn’t look clear enough.

This principle says if the government takes an action of huge economic or political importance, Congress must have clearly authorized it.

Massive tariffs on most imports qualify. A vague word like “regulate” doesn’t look clear enough.

The Supreme Court has already applied this doctrine.

• In 2022, it struck down EPA climate rules for lack of clear authority.

• In 2023, it blocked Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan.

Both involved huge policy moves without crystal-clear statutory backing. Trump’s tariffs fit that pattern.

• In 2022, it struck down EPA climate rules for lack of clear authority.

• In 2023, it blocked Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan.

Both involved huge policy moves without crystal-clear statutory backing. Trump’s tariffs fit that pattern.

Another principle is the Nondelegation Doctrine, which says Congress can’t hand off lawmaking power without clear guidelines.

Dormant since the 1930s, some justices want to revive it.

If IEEPA lets Trump set tariffs freely, it could be seen as Congress giving away its core taxing power.

Dormant since the 1930s, some justices want to revive it.

If IEEPA lets Trump set tariffs freely, it could be seen as Congress giving away its core taxing power.

Also relevant is the Youngstown case (1952), where the Court blocked Truman from seizing steel mills during the Korean War for lack of clear authority.

Justice Jackson’s framework said presidents are strongest with laws, weakest against Congress’s will.

Trump may fall in that weakest zone.

Justice Jackson’s framework said presidents are strongest with laws, weakest against Congress’s will.

Trump may fall in that weakest zone.

So what are Trump’s odds? Case for him:

• SCOTUS often defers to presidents on emergencies tied to foreign affairs.

• Nixon’s surcharge survived review.

• A conservative 6–3 Court might lean executive-friendly.

Those are his strongest arguments.

• SCOTUS often defers to presidents on emergencies tied to foreign affairs.

• Nixon’s surcharge survived review.

• A conservative 6–3 Court might lean executive-friendly.

Those are his strongest arguments.

Case against him:

• IEEPA doesn’t mention tariffs, while other statutes do.

• Congress in 1977 wanted to narrow emergency powers.

• Major Questions doctrine applies squarely.

• Letting one man set taxes without limits cuts against separation of powers.

That’s why experts say he’ll likely lose.

• IEEPA doesn’t mention tariffs, while other statutes do.

• Congress in 1977 wanted to narrow emergency powers.

• Major Questions doctrine applies squarely.

• Letting one man set taxes without limits cuts against separation of powers.

That’s why experts say he’ll likely lose.

Bloomberg Intelligence estimates Trump has a 60% chance of losing.

That’s not a slam dunk, but the odds lean against him.

Most legal scholars agree the Court won’t casually let one president rewrite the tariff code with a single proclamation.

That’s not a slam dunk, but the odds lean against him.

Most legal scholars agree the Court won’t casually let one president rewrite the tariff code with a single proclamation.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent insists the Court will uphold Trump’s tariffs.

But he’s also preparing “Plan B” routes under Section 232 (national security tariffs) or Section 301 (retaliatory tariffs).

That preparation signals even the administration knows IEEPA is shaky ground.

But he’s also preparing “Plan B” routes under Section 232 (national security tariffs) or Section 301 (retaliatory tariffs).

That preparation signals even the administration knows IEEPA is shaky ground.

If Trump loses:

• Importers can seek refunds on billions in duties.

• The U.S. Treasury loses a steady revenue stream.

• Businesses importing goods see lower costs.

• Consumers get some price relief.

And future presidents will need Congress for broad tariff actions.

• Importers can seek refunds on billions in duties.

• The U.S. Treasury loses a steady revenue stream.

• Businesses importing goods see lower costs.

• Consumers get some price relief.

And future presidents will need Congress for broad tariff actions.

If Trump wins:

• The presidency gains a permanent emergency tax lever.

• Any future president could declare an “economic emergency” and impose tariffs unilaterally.

• Markets would build in constant “tariff risk.”

• Allies and rivals would brace for sudden shocks.

• The presidency gains a permanent emergency tax lever.

• Any future president could declare an “economic emergency” and impose tariffs unilaterally.

• Markets would build in constant “tariff risk.”

• Allies and rivals would brace for sudden shocks.

Historical lessons: The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (1930) triggered retaliation and helped deepen the Great Depression.

Nixon’s 1971 surcharge worked because it was temporary and tied to a real crisis.

Broad, indefinite tariffs like Trump’s risk repeating history’s worst mistakes.

Nixon’s 1971 surcharge worked because it was temporary and tied to a real crisis.

Broad, indefinite tariffs like Trump’s risk repeating history’s worst mistakes.

So will Trump win? He has a path if the Court defers broadly to presidential emergency power.

But text, history, and doctrine tilt against him.

Odds lean 60–70% that Trump loses, with justices saying IEEPA was never meant to be a blank check for global tariffs.

But text, history, and doctrine tilt against him.

Odds lean 60–70% that Trump loses, with justices saying IEEPA was never meant to be a blank check for global tariffs.

Bottom line: This is bigger than trade. It’s about who holds the power to tax Congress or the president.

The Supreme Court’s ruling will redraw the line between speed and separation of powers.

Whatever the outcome, it sets a precedent that shapes American governance for decades.

The Supreme Court’s ruling will redraw the line between speed and separation of powers.

Whatever the outcome, it sets a precedent that shapes American governance for decades.

If you found these insights valuable: Sign up for my FREE newsletter! thestockmarket.news

I hope you've found this thread helpful.

Follow me @_Investinq for more.

Like/Repost the quote below if you can:

Follow me @_Investinq for more.

Like/Repost the quote below if you can:

https://x.com/_investinq/status/1963439929289060432?s=46

My gut says he will win but logic says he will lose. I guess, we will find out soon!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh