Imagine building a new house. You think cement and steel, but what about plumbing, wires, paint, tiles, woodwork, sanitaryware? That simple cement exercise pulls in a whole bunch of industries, collectively known as "building materials."🧵👇

A house isn't just walls and a roof. To actually live in it, you'll need water and electricity. That means plumbing, wires, cables. Then comes the part where you want it to look good. So you paint it, do waterproofing, lay tiles.

For finishing touches, you'll add woodwork, sanitaryware, and furniture. What started as simple exercise in cement ends up pulling in whole bunch of industries. Each sub-segment is massive, worth thousands of crores with mixed organized and unorganized players.

If we covered every single one in depth, it'd take more than just one article. Analysts treat cement, steel, paints, cables as separate industries. Under "building materials," they include pipes, wood, and tiles/ceramics. That's the lens we'll use.

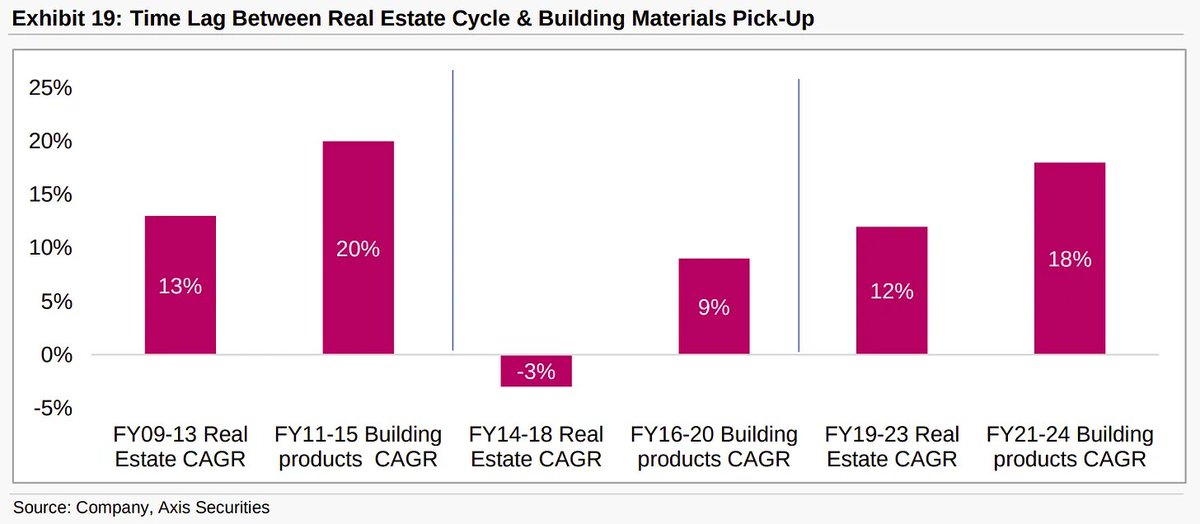

Three dynamics stood out while digging deeper. First, while tied to construction activity, building materials typically lag the real estate cycle by about two years and often deliver higher growth rates.

First, construction doesn't start the day demand picks up, it takes time for approvals, financing, planning. Products like tiles, bathware, finishes come at the end of timeline. That's why you see them booming even when real estate demand plateaus.

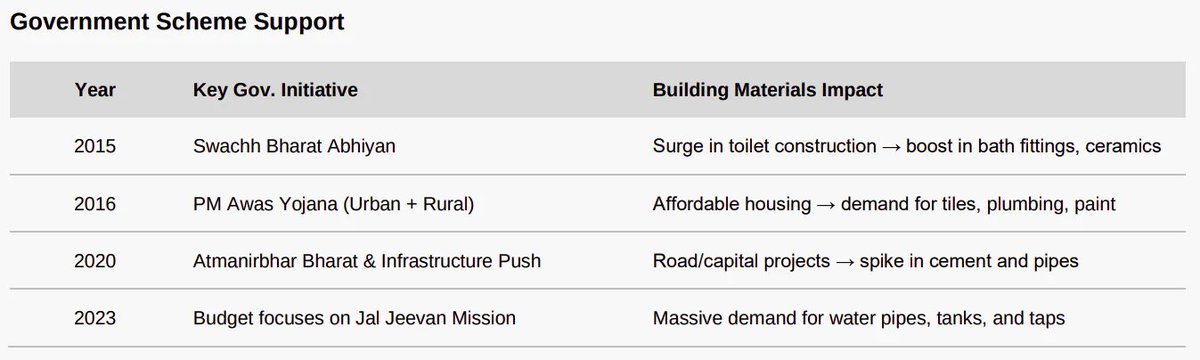

Second, it's not just the real estate cycle at play. Government spending, whether on infrastructure, housing, rural development, or sanitation, drives demand across sub-segments in very different ways.

Infra-led spends like highways or irrigation immediately boost demand for steel, pipes, other early-stage materials. Housing and urban schemes move slower as funds are released in phases, demand for finishes like tiles, bathware kicks in 6-18 months after approvals.

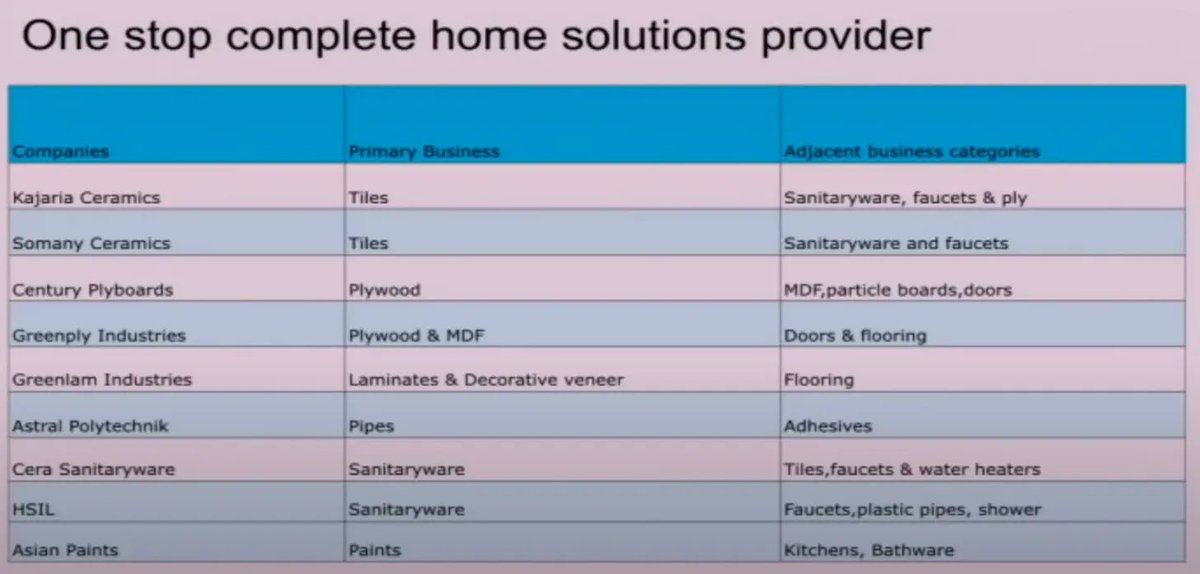

Third, players rarely stay confined to one niche. Purchase points overlap, so companies cross into adjacent categories. Walk into tile dealer, you'll pick up bathroom fittings and sanitaryware at same place. Plywood company branches into MDF.

The logic is simple, segments are interconnected, customers often buy across them in one go. If you're looking at building materials industry, it helps to view it as constantly evolving ecosystem.

If there's one corner investors keep circling back to, it's plastic pipes. Usually steady, predictable, no-nonsense industry. Except this quarter. First couple months looked fine, dealers moved volumes, government projects gave support.

Then June rains threw wrench into plans. Early monsoon spoiled everything, soaked up demand. Remember, whenever there's incessant rain construction activity halts, directly impacting industry. Sales slowed, dealers refused to stock up, insiders called it toughest month in years.

What made things worse was PVC prices, the raw material behind pipes. PVC prices often at mercy of factors beyond our control, price of crude oil which is used to make PVC, currency volatility, others. Due to these factors, PVC price behavior left everyone guessing.

Prices dropped early, only to bounce back later. Manufacturers took hits on balance sheets as inventory values dropped, while dealers played it safe, decided not to stock up inventory. Companies tried increasing volumes by offering higher incentives.

But that only hurt profitability even more. Gap between leaders and laggards became obvious. Bigger names like Supreme Industries and Astral Limited still managed to hold margins together, thanks to brand strength and side businesses. Smaller players like Prince Pipes struggled.

Growth in volumes across industry was patchy at best, flat at worst. Real issue was overall sentiment, nobody wanted to carry excess stock with unpredictable PVC prices and policy clouds hanging overhead. Hope is next quarter brings seasonal demand, project restarts.

Tiles story not all that different. First half of Q1 had momentum, domestic demand steady, exports seemed set to pick up, companies rolled out modest price hikes. By late May, story flipped. Tile exports stumbled thanks to fresh US tariffs.

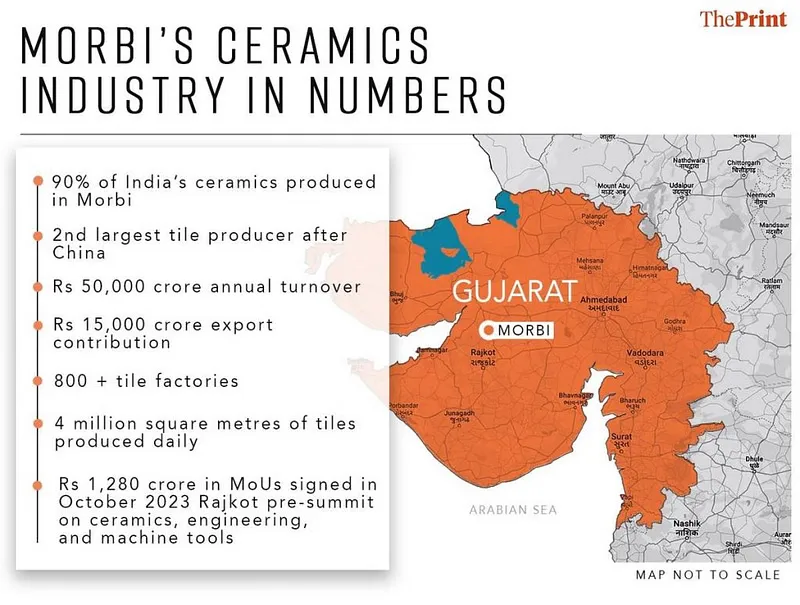

US accounts for 7.2% of Indian tiles exports in FY25, reasonable to expect demand from US will continue to be weak. Domestic market has been cut-throat. Morbi in Gujarat, The Ceramic Capital of India, home to over 800 tile factories crammed into 60-kilometre radius.

Morbi accounts for 90% of India's tile production, India is 2nd only to China. As per government data, annual turnover about ₹50,000 crore, with exports constituting ₹15,000 crore. Factories have been pushing volumes non-stop, naturally led to over-supply.

This made it impossible for branded players to pass on higher costs. June delivered dampener on growth. Early monsoon slowed construction, demand dried up, tile makers left scraping by, recording dismal low single-digit growth rates.

Kajaria and Somany, two biggest tile players, both inched ahead but only off weaker base than expected. Prices stayed flat, revenues barely moved. Kajaria's operating margins slipped nearly 2 percentage points from last year to 13%, Somany held around 8%.

For wood panel industry, Q1 FY26 was supposed to be about recovery. Real estate sales over last couple years set up demand pipeline for more wood. After staying stubbornly high for long, timber prices finally showed signs of softening. But reality was messy.

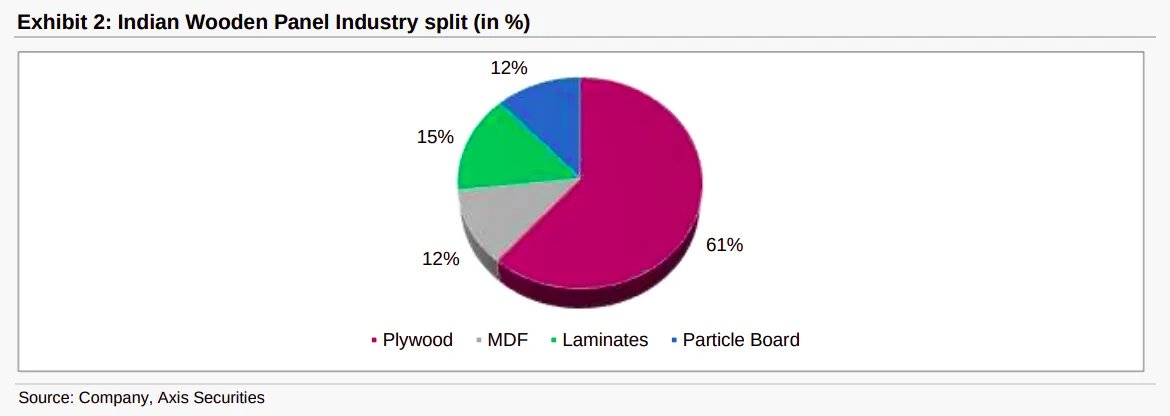

Despite softening prices, demand muted across all segments, plywood, MDF, laminates, particle board. MDF was once poster child, supposed to eat share from other segments, but faced heavy headwinds. Imports risen anticipating anti-dumping duty changes, new domestic capacities kept market oversupplied.

Common thread across pipes, tiles, wood, Q1 FY26 followed same script. April and May gave hope, June's early monsoon killed it. Analysts called it weather-and-cost quarter. For investors, takeaway is blunt, Q2 decides the year. If construction bounces back, industry breathes again.

We cover this and one more interesting story in today's edition of The Daily Brief. Watch on YouTube, read on Substack, or listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

All links here:thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/indias-build…

All links here:thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/indias-build…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh