🔬Viruses don’t just cause short-term illness.

Many stay in your body for life.

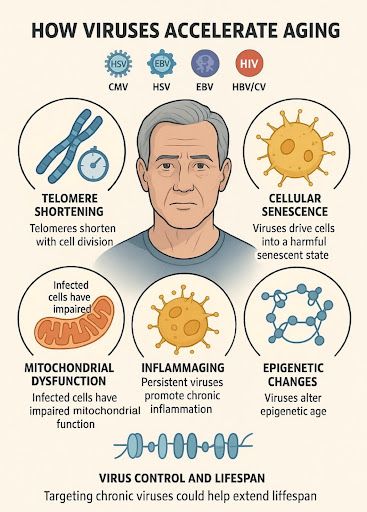

They speed up the aging process - in your immune system, organs, and even your DNA.

Here’s some examples, and why stopping them could help extend lifespan🧵

Many stay in your body for life.

They speed up the aging process - in your immune system, organs, and even your DNA.

Here’s some examples, and why stopping them could help extend lifespan🧵

Common long-term viruses include:

- CMV (cytomegalovirus)

- HSV (herpes simplex, cold sores)

- EBV (Epstein-Barr, mono)

- HIV

- HBV and HCV (hepatitis B and C)

These viruses often remain in the body for years, even decades.

- CMV (cytomegalovirus)

- HSV (herpes simplex, cold sores)

- EBV (Epstein-Barr, mono)

- HIV

- HBV and HCV (hepatitis B and C)

These viruses often remain in the body for years, even decades.

They cause damage over time, even when you don’t feel sick.

Researchers have found that these viruses speed up many of the same processes that happen during normal aging.

Researchers have found that these viruses speed up many of the same processes that happen during normal aging.

One example: telomeres - protective caps at the ends of your DNA.

They get shorter as you age.

People with chronic infections have much shorter telomeres, especially in their immune cells, even at younger ages.

They get shorter as you age.

People with chronic infections have much shorter telomeres, especially in their immune cells, even at younger ages.

Short telomeres mean cells can’t divide properly.

This leads to weaker immune function, more inflammation, and higher risk of age-related diseases.

This leads to weaker immune function, more inflammation, and higher risk of age-related diseases.

Viruses also cause some cells to enter a “shutdown” state.

These are called senescent cells.

They don’t die, but they release harmful signals that affect nearby healthy cells.

These are called senescent cells.

They don’t die, but they release harmful signals that affect nearby healthy cells.

This contributes to chronic inflammation in tissues - seen in diseases like arthritis, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s.

Some viruses cause this directly. For example, COVID-19 can trigger senescent cells in the lungs.

Some viruses cause this directly. For example, COVID-19 can trigger senescent cells in the lungs.

Mitochondria - the energy source in your cells - also take a hit.

Viruses like HIV and hepatitis C damage mitochondria in immune cells, leading to more stress, less energy, and faster aging.

Viruses like HIV and hepatitis C damage mitochondria in immune cells, leading to more stress, less energy, and faster aging.

This results in “tired” immune cells that don’t work as well, similar to those found in much older people.

Many viruses also keep the immune system constantly activated.

This causes long-term, low-level inflammation - sometimes called “inflammaging.”

This causes long-term, low-level inflammation - sometimes called “inflammaging.”

For example, people with CMV (a very common lifelong virus) have higher levels of inflammatory molecules in their blood.

This increases the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

This increases the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

Some viruses even change how your genes are regulated - what’s known as epigenetic aging.

People with HIV or CMV often show signs of being biologically years older than their actual age.

People with HIV or CMV often show signs of being biologically years older than their actual age.

These epigenetic changes can affect how your body repairs itself, fights disease, and maintains organ function.

And they can last even after the virus is under control.

And they can last even after the virus is under control.

Let’s look at some examples from human studies:

People with high numbers of chronic infections have shorter telomeres.

HIV+ people, even on treatment, show signs of faster aging (in immune function, inflammation, and DNA changes).

CMV is linked to poor vaccine response and higher frailty in older adults.

People with high numbers of chronic infections have shorter telomeres.

HIV+ people, even on treatment, show signs of faster aging (in immune function, inflammation, and DNA changes).

CMV is linked to poor vaccine response and higher frailty in older adults.

In animal studies:

- Infected monkeys age faster at the genetic and immune level.

- Mice with long-term viral infections have more inflammation and die younger.

- Infected fruit flies lose gut function earlier and have shorter lifespans.

- Infected monkeys age faster at the genetic and immune level.

- Mice with long-term viral infections have more inflammation and die younger.

- Infected fruit flies lose gut function earlier and have shorter lifespans.

So what can be done?

There are ways in development that may reduce or slow down this virus-driven aging - through prevention, treatment, and new therapies.

There are ways in development that may reduce or slow down this virus-driven aging - through prevention, treatment, and new therapies.

CRISPR-based gene editing is being tested to remove viruses from the body entirely.

- Early HIV trials show partial success.

- Lab studies show this could work for herpes and hepatitis B as well.

- Early HIV trials show partial success.

- Lab studies show this could work for herpes and hepatitis B as well.

Senolytics - drugs that remove senescent cells - may help reverse some of the damage.

In mouse studies, they reduced lung damage caused by COVID by clearing these aged, damaged cells.

In mouse studies, they reduced lung damage caused by COVID by clearing these aged, damaged cells.

Researchers are also working on immune-boosting therapies to help the body better control chronic viruses without ongoing damage.

In short:

Chronic viruses can quietly speed up aging in the immune system, liver, brain, and elsewhere.

They make your body behave like it’s older than it is.

Chronic viruses can quietly speed up aging in the immune system, liver, brain, and elsewhere.

They make your body behave like it’s older than it is.

Preventing and controlling these infections could become part of how we slow down aging, reduce disease risk, and extend healthy lifespan.

This is just another example of how viruses cause negative effects in the human body past the acute illness phase.

Research into post viral diseases like Long COVID & ME/CFS may also help uncover mechanisms in which viruses continue to effect individuals post infection.

Research into post viral diseases like Long COVID & ME/CFS may also help uncover mechanisms in which viruses continue to effect individuals post infection.

You can follow our research @amaticahealth on our website and join the projects yourself to help progress research:

amaticahealth.com

amaticahealth.com

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh