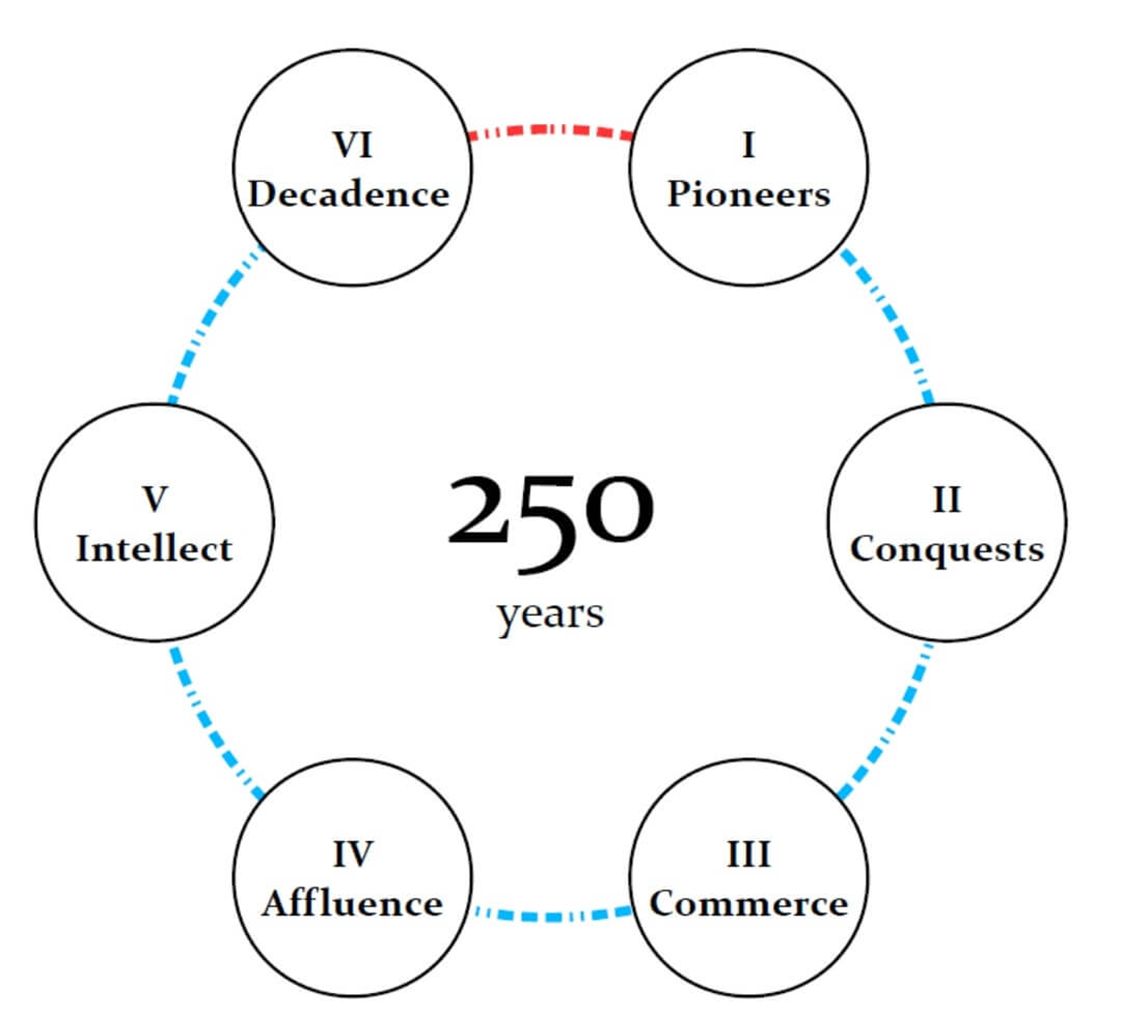

All empires repeat the same cycle, says 20th-century historian John Glubb.

He observed that for the past 3000 years every civilization has followed the same 6 stages before decline—what are they?🧵

He observed that for the past 3000 years every civilization has followed the same 6 stages before decline—what are they?🧵

Sir John Bagot Glubb was a British soldier and author who served as the commanding general for Transjordan's Arab Legion from 1939 to 1956.

In his later years he wrote about geopolitics and world history, and penned a succinct description of how civilizations rise and fall…

In his later years he wrote about geopolitics and world history, and penned a succinct description of how civilizations rise and fall…

Glubb’s 1978 work, “The Fate of Empires and the Search for Survival,” is an idea-dense essay that argues all great empires follow an eerily similar pattern.

From observing 11 distinct cultures, Glubb draws some intriguing conclusions that have implications for modern society.

From observing 11 distinct cultures, Glubb draws some intriguing conclusions that have implications for modern society.

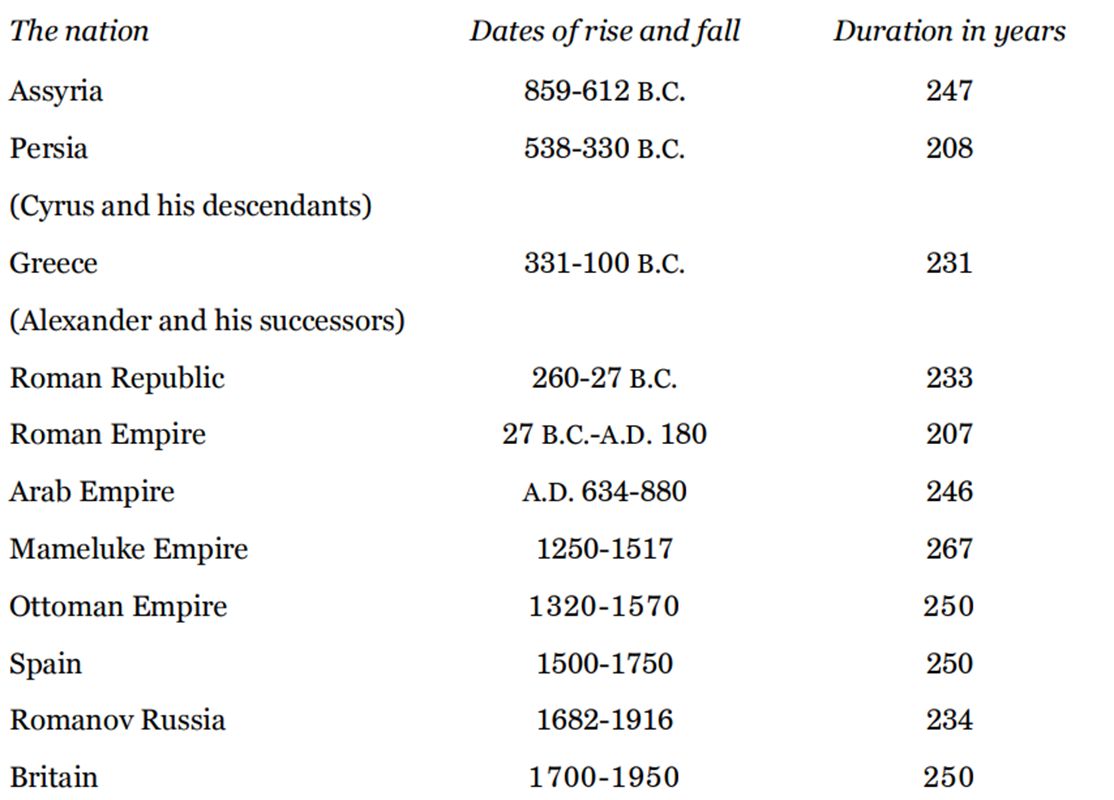

Glubb first notes that empires generally decline after ~250 years, or 10 human generations.

Though there are exceptions, a remarkable similarity in life spans emerges when one compares them side-by-side.

*Note: His conception of decline was not necessarily "destruction".

Though there are exceptions, a remarkable similarity in life spans emerges when one compares them side-by-side.

*Note: His conception of decline was not necessarily "destruction".

Glubb writes:

“In spite of the accidents of fortune, and the apparent circumstances of the human race at different epochs, the periods of duration of different empires at varied epochs show a remarkable similarity.”

“In spite of the accidents of fortune, and the apparent circumstances of the human race at different epochs, the periods of duration of different empires at varied epochs show a remarkable similarity.”

And the trend holds regardless of a civilization’s technological level:

“The Assyrians marched on foot and fought with spears…The British used artillery, railways and ocean-going ships. Yet the two empires lasted for approximately the same periods.”

“The Assyrians marched on foot and fought with spears…The British used artillery, railways and ocean-going ships. Yet the two empires lasted for approximately the same periods.”

The first stage of an empire, Glubb claims, is the Age of Pioneers, or “the outburst”.

This is where a small, seemingly insignificant nation emerges from its homeland and establishes a presence on the world stage. The outburst is characterized by energy, courage, and creativity.

This is where a small, seemingly insignificant nation emerges from its homeland and establishes a presence on the world stage. The outburst is characterized by energy, courage, and creativity.

Glubb describes the new conquerors as “normally poor, hardy and enterprising and above all aggressive.”

Unbound by established traditions, they rely on improvisation and experimentation:

“If one method fails, they try something else.”

Unbound by established traditions, they rely on improvisation and experimentation:

“If one method fails, they try something else.”

Glubb gives the example of Macedon in the 4th century:

“Prior to Philip (359-336 B.C.), Macedon had been an insignificant state to the north of Greece…Yet by 323 B.C., thirty-six years after the accession of Philip…the Macedonian Empire extended from the Danube to India…”

“Prior to Philip (359-336 B.C.), Macedon had been an insignificant state to the north of Greece…Yet by 323 B.C., thirty-six years after the accession of Philip…the Macedonian Empire extended from the Danube to India…”

The second stage is called the Age of Conquests.

The sophistication of aging civilizations are adopted by the rising power. Thus, their expansion consists of “organised, disciplined and professional campaigns.”

This is where the culture becomes a bona fide “empire”.

The sophistication of aging civilizations are adopted by the rising power. Thus, their expansion consists of “organised, disciplined and professional campaigns.”

This is where the culture becomes a bona fide “empire”.

This stage is characterized by confidence, optimism, and contempt for “decadent” cultures whom they’ve conquered.

The people of the new empire are practical in both government and war.

The people of the new empire are practical in both government and war.

Moreover, Glubb notes that their lack of tradition allows their leadership a freedom to try new things:

“...the leaders are free to use their own improvisations, not having studied politics or tactics in schools or in textbooks.”

“...the leaders are free to use their own improvisations, not having studied politics or tactics in schools or in textbooks.”

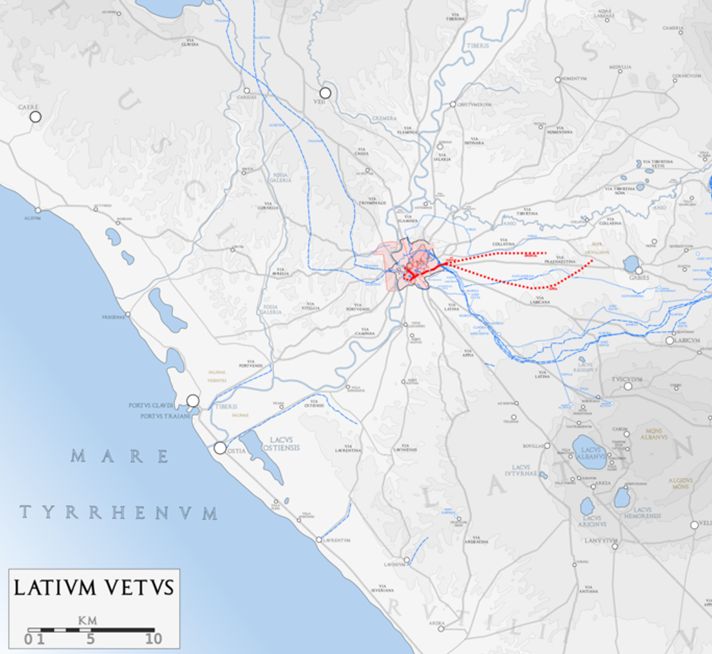

Next comes the Age of Commerce.

With the acquisition of vast areas of land, commerce becomes easy and safe for the empire’s citizens. Resources, people, and ideas are exchanged over great distances. And if the empire is large, a great variety of products are produced.

With the acquisition of vast areas of land, commerce becomes easy and safe for the empire’s citizens. Resources, people, and ideas are exchanged over great distances. And if the empire is large, a great variety of products are produced.

The Age of Commerce often overlaps with the Age of Conquests, but the public's values begin to shift:

“The proud military traditions still hold sway and the great armies guard the frontiers, but gradually the desire to make money seems to gain hold of the public”

“The proud military traditions still hold sway and the great armies guard the frontiers, but gradually the desire to make money seems to gain hold of the public”

An honor culture is replaced by a mercantile one:

“During the military period, glory and honour were the principal objects of ambition. To the merchant, such ideas are but empty words, which add nothing to the bank balance.”

“During the military period, glory and honour were the principal objects of ambition. To the merchant, such ideas are but empty words, which add nothing to the bank balance.”

The Age of Affluence comes next, and is a natural consequence of the Age of Commerce.

Monetary gain becomes the sole pursuit:

“…the Age of Affluence silences the voice of duty. The object of the young and the ambitious is no longer fame, honour or service, but cash.”

Monetary gain becomes the sole pursuit:

“…the Age of Affluence silences the voice of duty. The object of the young and the ambitious is no longer fame, honour or service, but cash.”

The fighting spirit of the empire fades as leaders buy off enemies rather than fight them:

“…subsidies instead of weapons are employed to buy off enemies…Military readiness, or aggressiveness, is denounced as primitive and immoral. Civilised peoples are too proud to fight.”

“…subsidies instead of weapons are employed to buy off enemies…Military readiness, or aggressiveness, is denounced as primitive and immoral. Civilised peoples are too proud to fight.”

The fifth stage in Glubb’s model is the Age of Intellect—a period of scholarly activity that coincides with decline. Whereas in the Age of Affluence the merchant class patronized the arts, now colleges and universities are given immense funding.

Glubb noted that in his own time, he saw the US and Britain as undergoing this phase:

“When these nations were at the height of their glory, Harvard, Yale, Oxford and Cambridge seemed to meet their needs. Now almost every city has its university.”

“When these nations were at the height of their glory, Harvard, Yale, Oxford and Cambridge seemed to meet their needs. Now almost every city has its university.”

And once again the energy of the society is directed toward a new goal:

“The ambition of the young, once engaged in the pursuit of adventure and military glory, and then in the desire for the accumulation of wealth, now turns to the acquisition of academic honours.”

“The ambition of the young, once engaged in the pursuit of adventure and military glory, and then in the desire for the accumulation of wealth, now turns to the acquisition of academic honours.”

The final stage of an empire is the Age of Decadence. It’s characterized by a number of symptoms:

-internal division

-an influx of foreigners

-materialism and frivolity

-a welfare state

-weakening religion

-a defensive mindset

-internal division

-an influx of foreigners

-materialism and frivolity

-a welfare state

-weakening religion

-a defensive mindset

Empires decline amidst a “cacophony of argument”. Glubb writes that “endless and incessant talking” fails to solve political and social disagreements:

“Amid a Babel of talk, the ship drifts on to the rocks.”

“Amid a Babel of talk, the ship drifts on to the rocks.”

This is because cleverness cannot solve problems that require self-sacrifice:

“...there are times when the perhaps unsophisticated self-dedication of the hero is more essential than the sarcasms of the clever.”

“...there are times when the perhaps unsophisticated self-dedication of the hero is more essential than the sarcasms of the clever.”

Glubb notes that internal strife is a hallmark of decline and gives the Byzantine Empire as a prime example. Civil wars and infighting preoccupied the empire until the Ottomans were already on their doorstep.

“Strikes, demonstrations, boycotts and similar activities” are prevalent in the last stage of empire, and internal strife is exacerbated by external conflict. Rather than unifying around a potential threat, the nation pulls itself apart.

An influx of foreigners, usually concentrated in cities, accompanies a civilization’s decline. Glubb claims that when a culture is homogeneous, there is a feeling of “solidarity and comradeship” among the people, but a large number of foreigners disrupts this.

Foreigners disrupt the unity of the empire due to a few reasons:

1) their nature often differs from that of the original imperial stock

2) in hard times they are less willing to sacrifice their lives and their property

3) they are liable to form communities of their own

4) there may be resentment among those who were previously conquered by the imperial race

1) their nature often differs from that of the original imperial stock

2) in hard times they are less willing to sacrifice their lives and their property

3) they are liable to form communities of their own

4) there may be resentment among those who were previously conquered by the imperial race

Glubb notes that these problems are not due to superiority or inferiority of any race, rather because there are natural differences between them that makes a single culture difficult to maintain.

In his time, he noticed an influx of migrants to the declining British Empire:

“In London today, Cypriots, Greeks, Italians, Russians, Africans, Germans and Indians jostle one another on the buses and in the underground, so that it sometimes seems difficult to find any British.”

“In London today, Cypriots, Greeks, Italians, Russians, Africans, Germans and Indians jostle one another on the buses and in the underground, so that it sometimes seems difficult to find any British.”

Frivolity is also a sign of decline. Glubb claims that this mindset is rooted in pessimism:

“Let us eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die.”

“Let us eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die.”

Decadence is ultimately a spiritual sickness resulting from too long a period of wealth and power. Cynicism, decline of religion, pessimism, and frivolity follow.

No effort is made to save the nation, because its citizens no longer believe anything is worth saving.

No effort is made to save the nation, because its citizens no longer believe anything is worth saving.

Glubb saw the similarities between empires’ lifespans as a reason to teach history differently.

Rather than focusing on particular nations or periods, the history of the whole human race should be taught.

Rather than focusing on particular nations or periods, the history of the whole human race should be taught.

He concluded:

“... if we studied calmly and impartially the history of human institutions and development over these four thousand years, should we not reach conclusions which would assist to solve our problems today?

“... if we studied calmly and impartially the history of human institutions and development over these four thousand years, should we not reach conclusions which would assist to solve our problems today?

What do you think of Glubb’s analysis—do empires follow similar cycles? Are we destined to repeat the patterns of civilizations who came before us?

And if so, which of Glubb’s stages are we currently in?

And if so, which of Glubb’s stages are we currently in?

We dive deeper into topics like this in our newsletter.

In-depth articles straight to your inbox every week (free)👇

thinkingwest.substack.com

In-depth articles straight to your inbox every week (free)👇

thinkingwest.substack.com

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh