F-35 Joint Strike Fighter: Current Status and UK Implications

Part of my wider series on F-35. As always, views my own - facts can and should be corrected if wrong.

This follows the GAO report.

1/25 The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter remains a critical asset in modern military aviation, blending stealth, advanced sensors, and networked systems to bolster combat prowess for the United States and its allies. As outlined in the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report just released (and getting lots of attention), the programme has delivered over 1,100 aircraft since production commenced in 2006. However, it continues to face substantial cost overruns and schedule delays. Total acquisition costs now surpass $485 billion, an $89.5 billion rise from the 2012 baseline, primarily due to modernisation efforts. Sustainment costs over the aircraft’s 77-year lifecycle are projected at $1.58 trillion, pushing the overall expense beyond $2 trillion.

For us (United Kingdom), a key (tier 1) partner contributing to development, production, and sustainment, these issues manifest as operational shortfalls and strategic risks. This thread tries to explore the F-35’s status, emphasising UK effects, drawing on the GAO report and other recent developments.

Part of my wider series on F-35. As always, views my own - facts can and should be corrected if wrong.

This follows the GAO report.

1/25 The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter remains a critical asset in modern military aviation, blending stealth, advanced sensors, and networked systems to bolster combat prowess for the United States and its allies. As outlined in the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report just released (and getting lots of attention), the programme has delivered over 1,100 aircraft since production commenced in 2006. However, it continues to face substantial cost overruns and schedule delays. Total acquisition costs now surpass $485 billion, an $89.5 billion rise from the 2012 baseline, primarily due to modernisation efforts. Sustainment costs over the aircraft’s 77-year lifecycle are projected at $1.58 trillion, pushing the overall expense beyond $2 trillion.

For us (United Kingdom), a key (tier 1) partner contributing to development, production, and sustainment, these issues manifest as operational shortfalls and strategic risks. This thread tries to explore the F-35’s status, emphasising UK effects, drawing on the GAO report and other recent developments.

Programme Challenges: Cost Escalations and Delays

2/25 The GAO highlights modernisation as the chief culprit for inefficiencies. The Block 4 effort, a $16.5 billion initiative to enhance hardware and software for capabilities like new weapons and radar improvements, is over $6 billion above original estimates and at least five years delayed, with completion now eyed beyond 2031.

The programme is trimming Block 4 scope to prioritise deliverable elements by 2031.

A critical enabler, Technology Refresh 3 (TR-3)—a $1.9 billion hardware-software suite—has been a major bottleneck, but recent updates indicate completion of software upgrades in June 2025, rendering aircraft combat-capable. Despite this, TR-3 delays contributed to 72 aircraft deliveries in 2025 facing holdbacks.

Production woes persist: Contractors Lockheed Martin and Pratt & Whitney delivered all 110 aircraft and engines late in 2024, averaging 238 days behind schedule.

2/25 The GAO highlights modernisation as the chief culprit for inefficiencies. The Block 4 effort, a $16.5 billion initiative to enhance hardware and software for capabilities like new weapons and radar improvements, is over $6 billion above original estimates and at least five years delayed, with completion now eyed beyond 2031.

The programme is trimming Block 4 scope to prioritise deliverable elements by 2031.

A critical enabler, Technology Refresh 3 (TR-3)—a $1.9 billion hardware-software suite—has been a major bottleneck, but recent updates indicate completion of software upgrades in June 2025, rendering aircraft combat-capable. Despite this, TR-3 delays contributed to 72 aircraft deliveries in 2025 facing holdbacks.

Production woes persist: Contractors Lockheed Martin and Pratt & Whitney delivered all 110 aircraft and engines late in 2024, averaging 238 days behind schedule.

GAO Recommendations for Improvement

3/25 The GAO critiques incentive structures, noting Lockheed Martin earned millions despite delays, as contracts permitted up to 60 days’ lateness for partial rewards. Recommendations include assessing Lockheed’s delivery capacity, revising incentives for better alignment, and broadening leading practices like iterative design and digital twins.

These systemic issues affect all users, but international partners like the UK bear heightened risks from U.S.-led timelines. The GAO observes that while partner input is sought, delays in shared upgrades impede custom capabilities, often favouring U.S. priorities.

3/25 The GAO critiques incentive structures, noting Lockheed Martin earned millions despite delays, as contracts permitted up to 60 days’ lateness for partial rewards. Recommendations include assessing Lockheed’s delivery capacity, revising incentives for better alignment, and broadening leading practices like iterative design and digital twins.

These systemic issues affect all users, but international partners like the UK bear heightened risks from U.S.-led timelines. The GAO observes that while partner input is sought, delays in shared upgrades impede custom capabilities, often favouring U.S. priorities.

Software Hurdles: Core to Delays and Combat Readiness

4/25 Software remains central to F-35 setbacks, directly impacting usability. The GAO identifies immature TR-3 integrated core processor designs as a primary cause, leading to instability in weapons, sensors, and mission systems. Developmental testing uncovered bugs, prolonged by integration issues, supply chains, and insufficient infrastructure.

Without stable software, aircraft miss full Block 4 features, curtailing sensor fusion, threat detection, and precision strikes—key F-35 strengths. Non-combat-capable deliveries in 2024 limited use to training until 2025 upgrades. The GAO advocates iterative methods and virtual testing for faster resolutions, though adoption is partial.

4/25 Software remains central to F-35 setbacks, directly impacting usability. The GAO identifies immature TR-3 integrated core processor designs as a primary cause, leading to instability in weapons, sensors, and mission systems. Developmental testing uncovered bugs, prolonged by integration issues, supply chains, and insufficient infrastructure.

Without stable software, aircraft miss full Block 4 features, curtailing sensor fusion, threat detection, and precision strikes—key F-35 strengths. Non-combat-capable deliveries in 2024 limited use to training until 2025 upgrades. The GAO advocates iterative methods and virtual testing for faster resolutions, though adoption is partial.

UK-Specific Ramifications: Dependency on U.S. Timelines

5/25 For the UK, software delays ripple into national initiatives. U.S. prioritisation of its weapons may defer partner needs, given joint governance favours American requirements. As of September 2025, we operate 37 F-35Bs, with “plans” for 138 total (likely 72ish) , including 12 F-35As announced in June 2025 for nuclear and conventional roles. This shift, per the 2025 Strategic Defence Review, supposedly bolsters NATO commitments.

5/25 For the UK, software delays ripple into national initiatives. U.S. prioritisation of its weapons may defer partner needs, given joint governance favours American requirements. As of September 2025, we operate 37 F-35Bs, with “plans” for 138 total (likely 72ish) , including 12 F-35As announced in June 2025 for nuclear and conventional roles. This shift, per the 2025 Strategic Defence Review, supposedly bolsters NATO commitments.

SPEAR 3 Delays: A Critical Gap for UK F-35B

6/25 The UK’s F-35B, flown by the RAF and RN, illustrates U.S.-centric delays’ impact. The MBDA SPEAR 3 package, designed for internal carriage enabling up to eight per aircraft for stealthy suppression of enemy air defences, faces integration postponement to the early 2030s due to supplier issues, shortages, and F-35 software delays. Originally planned for 2025, then 2028, and now early 2030’s - the timeline reflects low confidence.

6/25 The UK’s F-35B, flown by the RAF and RN, illustrates U.S.-centric delays’ impact. The MBDA SPEAR 3 package, designed for internal carriage enabling up to eight per aircraft for stealthy suppression of enemy air defences, faces integration postponement to the early 2030s due to supplier issues, shortages, and F-35 software delays. Originally planned for 2025, then 2028, and now early 2030’s - the timeline reflects low confidence.

Why Software Matters for SPEAR 3

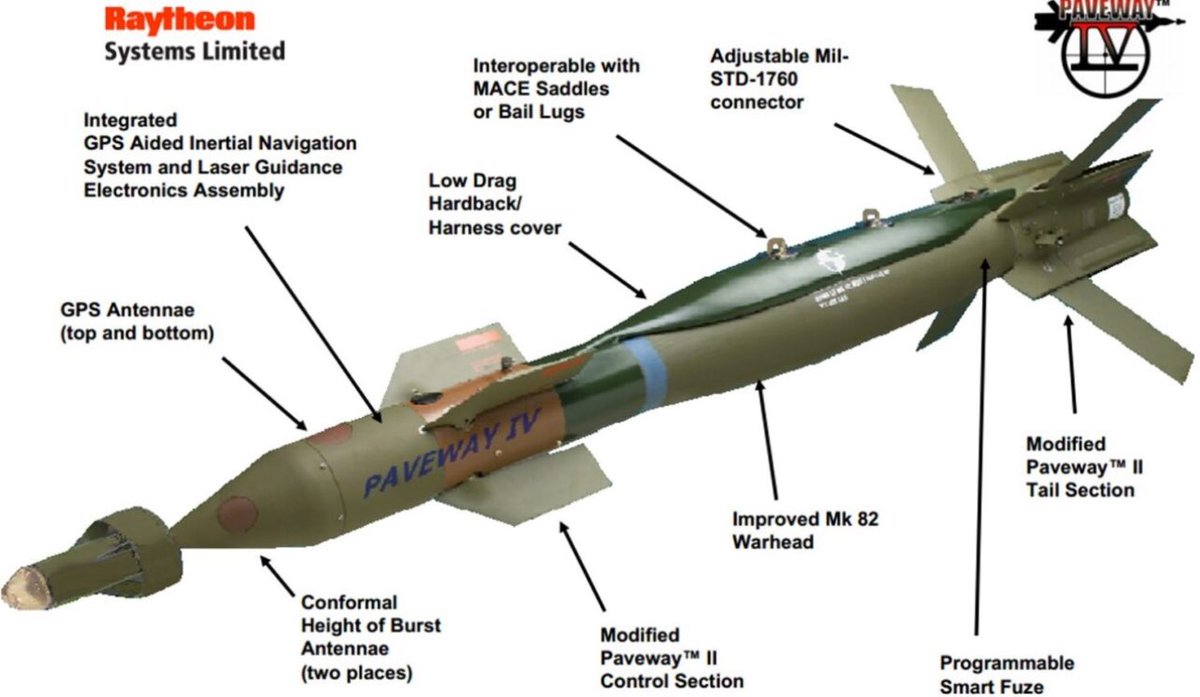

7/25 Block 4 and TR-3 updates are essential for SPEAR 3 compatibility with F-35 mission systems for targeting and guidance. Delays stem from U.S. focus on its integrations, like JASSM, (potentially) sidelining partners. Without SPEAR 3, the F-35B lacks deep-strike capability, failing Key User Requirements (KUR) for precision attacks while preserving stealth.

The UK is (potentially) looking at interim solutions like the U.S. StormBreaker bomb to bridge the gap.

7/25 Block 4 and TR-3 updates are essential for SPEAR 3 compatibility with F-35 mission systems for targeting and guidance. Delays stem from U.S. focus on its integrations, like JASSM, (potentially) sidelining partners. Without SPEAR 3, the F-35B lacks deep-strike capability, failing Key User Requirements (KUR) for precision attacks while preserving stealth.

The UK is (potentially) looking at interim solutions like the U.S. StormBreaker bomb to bridge the gap.

Broader F-35B Challenges: ODIN and Maintenance

8/25 Additional hurdles plague the UK F-35B. The ODIN maintenance system, replacing ALIS, has rolled out slowly in 2025, hampered by funding cuts and predictive analytics failures, causing spare parts shortages. A notable incident: A UK F-35B stranded in Thiruvananthapuram, India, since 14 June 2025, due to an unscheduled landing and parts delays (plus some other reasons I’ve covered in other threads on the F-35).

8/25 Additional hurdles plague the UK F-35B. The ODIN maintenance system, replacing ALIS, has rolled out slowly in 2025, hampered by funding cuts and predictive analytics failures, causing spare parts shortages. A notable incident: A UK F-35B stranded in Thiruvananthapuram, India, since 14 June 2025, due to an unscheduled landing and parts delays (plus some other reasons I’ve covered in other threads on the F-35).

MADL and Availability Issues

9/25 The Multifunction Advanced Data Link (MADL) limits networked operations amid general readiness woes, including corrosion identified in January 2025. Availability stands at one-third fully mission-capable, below targets, due to personnel shortages, infrastructure gaps, and supplier delays, lagging the global fleet average. Temporary boosts occurred for the April 2025 Carrier Strike Group deployment.

9/25 The Multifunction Advanced Data Link (MADL) limits networked operations amid general readiness woes, including corrosion identified in January 2025. Availability stands at one-third fully mission-capable, below targets, due to personnel shortages, infrastructure gaps, and supplier delays, lagging the global fleet average. Temporary boosts occurred for the April 2025 Carrier Strike Group deployment.

Carrier Enabled Power Projection (CEPP) and FOC

10/25 Without SPEAR 3 and full capabilities, the F-35B threatens Full Operating Capability (FOC) for CEPP and the Lightning Force. CEPP, integrating F-35Bs with Queen Elizabeth-class carriers, targets FOC by end-2025, demonstrated via the 2025 CSG deployment with up to 24 aircraft. This two-year delay from original plans undermines carrier strike ambitions. It’s not great - let’s see how they dress this up and get FOC without hitting KUR’s.

10/25 Without SPEAR 3 and full capabilities, the F-35B threatens Full Operating Capability (FOC) for CEPP and the Lightning Force. CEPP, integrating F-35Bs with Queen Elizabeth-class carriers, targets FOC by end-2025, demonstrated via the 2025 CSG deployment with up to 24 aircraft. This two-year delay from original plans undermines carrier strike ambitions. It’s not great - let’s see how they dress this up and get FOC without hitting KUR’s.

Leadership Transition: Sir Rich Knighton as CDS

11/25 Air Chief Marshal (ACM) Sir Rich Knighton assumed the role of Chief of the Defence Staff on the 2nd of September (this week), succeeding Admiral Sir Tony Radakin. As former Senior Responsible Owner for CEPP and Chief of the Air Staff, his engineering expertise potentially equips him to tackle these gaps. We shall see, no NAD as of yet.

11/25 Air Chief Marshal (ACM) Sir Rich Knighton assumed the role of Chief of the Defence Staff on the 2nd of September (this week), succeeding Admiral Sir Tony Radakin. As former Senior Responsible Owner for CEPP and Chief of the Air Staff, his engineering expertise potentially equips him to tackle these gaps. We shall see, no NAD as of yet.

Knighton’s Familiarity with CEPP

12/25 Knighton’s prior roles make him intimately aware of CEPP challenges, including F-35B integration delays. Balancing user requirements against fiscal and programmatic realities will be one of his first key tests.

12/25 Knighton’s prior roles make him intimately aware of CEPP challenges, including F-35B integration delays. Balancing user requirements against fiscal and programmatic realities will be one of his first key tests.

DSEI 2025: Spotlight on Mitigations

13/25 The Defence and Security Equipment International (DSEI) exhibition, running from the 9-12th of September 2025 at ExCeL London, should intensify scrutiny. Commentators, politicians, and industry will expect updates on F-35 mitigations, such as interim weapons and software fixes. The UK continues to explore (RAF driven) options like additional F-35As for nuclear roles, but KUR shortfalls persist.

13/25 The Defence and Security Equipment International (DSEI) exhibition, running from the 9-12th of September 2025 at ExCeL London, should intensify scrutiny. Commentators, politicians, and industry will expect updates on F-35 mitigations, such as interim weapons and software fixes. The UK continues to explore (RAF driven) options like additional F-35As for nuclear roles, but KUR shortfalls persist.

Complex UK Air Domain: Typhoon Upgrades

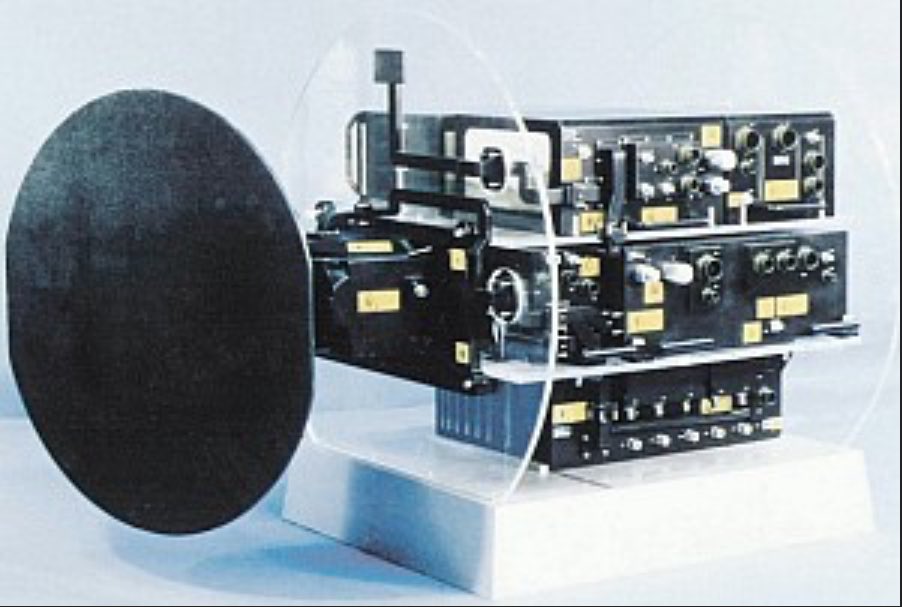

14/25 The UK’s air strategy is intricate amid pressures. Typhoon enhancements, including a further £204.6 million for the ECRS Mk2 radar, promise electronic warfare boosts from (earliest) 2028, with flight tests potentially concluding at the end-2025. Unions continually lobby for more Typhoons to sustain jobs and counter F-35 reliance.

14/25 The UK’s air strategy is intricate amid pressures. Typhoon enhancements, including a further £204.6 million for the ECRS Mk2 radar, promise electronic warfare boosts from (earliest) 2028, with flight tests potentially concluding at the end-2025. Unions continually lobby for more Typhoons to sustain jobs and counter F-35 reliance.

GCAP Introduction

15/25 The Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), partnering the UK, Japan, and Italy, targets a sixth-generation fighter by (optimistically) 2035. A joint venture launched in June 2025, with contracts anticipated by year-end, involves over 1,000 suppliers for economic benefits. Chances of new partners diminish as time goes on but we watch the France/Germany spat, like the Spanish, with interest.

15/25 The Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), partnering the UK, Japan, and Italy, targets a sixth-generation fighter by (optimistically) 2035. A joint venture launched in June 2025, with contracts anticipated by year-end, involves over 1,000 suppliers for economic benefits. Chances of new partners diminish as time goes on but we watch the France/Germany spat, like the Spanish, with interest.

Economic Context

16/25 These initiatives unfold against a UK economic outlook projecting 1.2-1.3% GDP growth in 2025, but with high borrowing costs lack of confidence in the economy, tempered by inflation, weak productivity, and trade tensions. Budget constraints could strain funding, defence isn’t high on the government agenda pressured by the NHS, social care and immigration concerns.

16/25 These initiatives unfold against a UK economic outlook projecting 1.2-1.3% GDP growth in 2025, but with high borrowing costs lack of confidence in the economy, tempered by inflation, weak productivity, and trade tensions. Budget constraints could strain funding, defence isn’t high on the government agenda pressured by the NHS, social care and immigration concerns.

Balancing Priorities in a Downward Outlook

17/25 With steady unemployment but domestic issues stifling growth, the new CDS must navigate these fiscal headwinds while advancing Typhoon, GCAP, and F-35 efforts whilst balancing all the other demands of an MoD that needs investment but also needs to manage obsolescence and potentially make more (visually) painful cuts to allow new investments to happen.

17/25 With steady unemployment but domestic issues stifling growth, the new CDS must navigate these fiscal headwinds while advancing Typhoon, GCAP, and F-35 efforts whilst balancing all the other demands of an MoD that needs investment but also needs to manage obsolescence and potentially make more (visually) painful cuts to allow new investments to happen.

Conclusion: Persistent Issues and UK Vulnerabilities

18/25 The F-35 programme’s challenges—rising costs, software delays, and production issues—underscore concurrency risks, as per the GAO report. For the UK, this means SPEAR 3 postponements to the 2030s, unmet KUR, and a delayed CEPP FOC until those requirements can be met. To declare FOC before the capability has been delivered (this is even before we discuss Crowsnest and a complete lack of organic AAR) would be disingenuous.

18/25 The F-35 programme’s challenges—rising costs, software delays, and production issues—underscore concurrency risks, as per the GAO report. For the UK, this means SPEAR 3 postponements to the 2030s, unmet KUR, and a delayed CEPP FOC until those requirements can be met. To declare FOC before the capability has been delivered (this is even before we discuss Crowsnest and a complete lack of organic AAR) would be disingenuous.

19/25 Low availability (one-third mission-capable), ODIN rollout delays, and MADL limitations erode readiness. The 12 F-35A acquisitions for nuclear roles and “training” offer some diversification but also reduce clarity as the RAF seek to regain a solid foothold in the F-35B programme (I expect comments on that one - by design).

20/25 Amid Typhoon ECRS Mk2 upgrades and GCAP progress, economic forecasts of 1.2-1.3% growth in 2025 present funding challenges which will have to be navigated and not ignored or pushed further to the right (the next parliament seems to be the current governments trick at the moment). The nettle has to be grasped - ambition and reality have to be balanced.

Challenges for the New CDS

21/25 ACM Sir Rich Knighton, fresh in post, faces reconciling those user needs with realities—advocating for mitigations at DSEI 2025 (9-12 September) while managing union calls for more Typhoons and GCAP ambitions. Something for the new NAD to understand as well.

21/25 ACM Sir Rich Knighton, fresh in post, faces reconciling those user needs with realities—advocating for mitigations at DSEI 2025 (9-12 September) while managing union calls for more Typhoons and GCAP ambitions. Something for the new NAD to understand as well.

22/25 Implementing GAO suggestions via enhanced practices could alleviate issues, but inaction risks diminishing UK air power in a contested world, especially as the delivery of air power changes in a world of “one way effectors) and 1960’s long range ballistic missiles.

23/25 Union lobbying underscores domestic stakes, with Typhoon production halting in July 2025 absent of new UK orders and no GCAP orders for the foreseeable future. Does the UK covert funds from F-35 to Typhoon?

24/25 Interim measures like StormBreaker and F-35A buys provide bridges, but core software and integration delays demand urgent transatlantic collaboration. What happens if the Uk buys Stormbreaker, does that mean SPEAR 3 gets cancelled, where will the money come from to pay for it? Satisfying short term operational needs against longer term strategic outcomes isn’t always the right answer.

Summary

25/25 The F-35’s travails highlight alliance dependencies, urging the UK to press for equitable progress. Knighton’s leadership arrives at a critical juncture—DSEI may reveal paths forward. For the rest of us these facts underscore the need for vigilance on readiness and investment. The GAO report isn’t great as articulated by @FTusa284 and @ValkStrategy and others.

What is the answer to the UK’s OCA and DCA et conundrum @gregbagwell @NavyLookout @WarshipsIFR

25/25 The F-35’s travails highlight alliance dependencies, urging the UK to press for equitable progress. Knighton’s leadership arrives at a critical juncture—DSEI may reveal paths forward. For the rest of us these facts underscore the need for vigilance on readiness and investment. The GAO report isn’t great as articulated by @FTusa284 and @ValkStrategy and others.

What is the answer to the UK’s OCA and DCA et conundrum @gregbagwell @NavyLookout @WarshipsIFR

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh