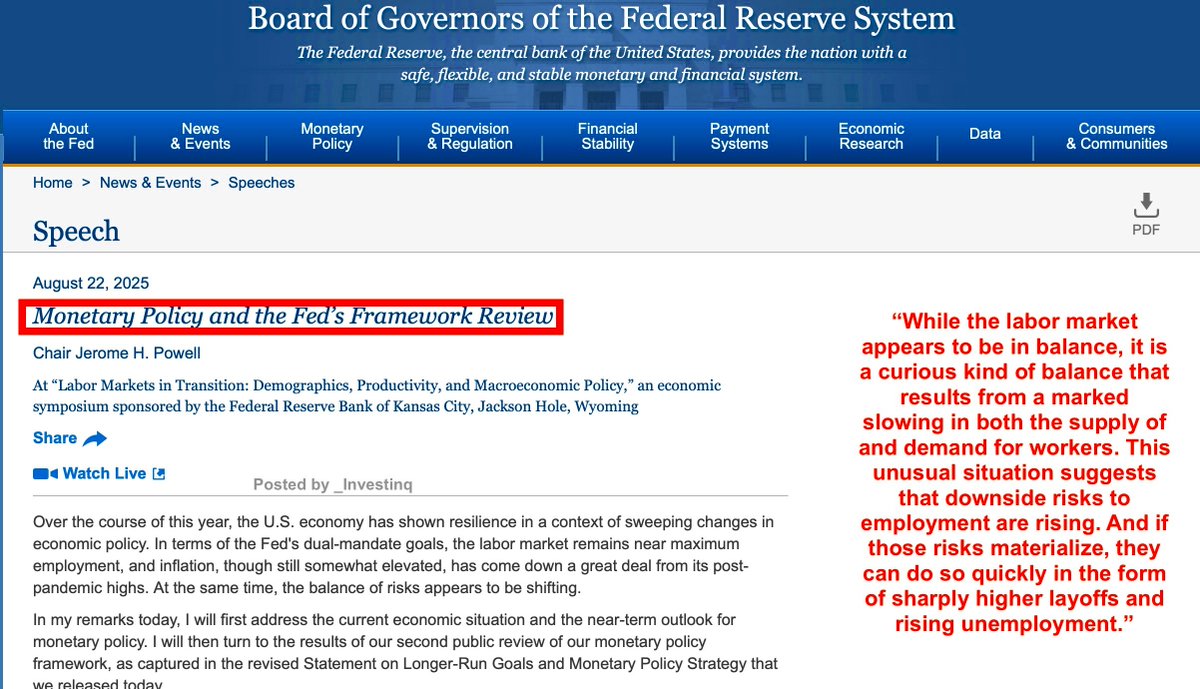

🚨 The U.S. just sold $100 billion in 4-week Treasury bills.

That’s the largest short-term auction in history.

This is the quietest move toward Yield Curve Control we’ve ever seen.

(a thread)

That’s the largest short-term auction in history.

This is the quietest move toward Yield Curve Control we’ve ever seen.

(a thread)

Let’s start with the big picture. The U.S. government spends more money than it collects in taxes.

That gap is called the deficit. To cover it, the government borrows.

It borrows by selling IOUs called Treasuries.

That gap is called the deficit. To cover it, the government borrows.

It borrows by selling IOUs called Treasuries.

Treasuries are promises. Investors lend the U.S. government money.

The government promises to pay them back later with interest.

This system is how America funds everything from Social Security checks to defense spending.

The government promises to pay them back later with interest.

This system is how America funds everything from Social Security checks to defense spending.

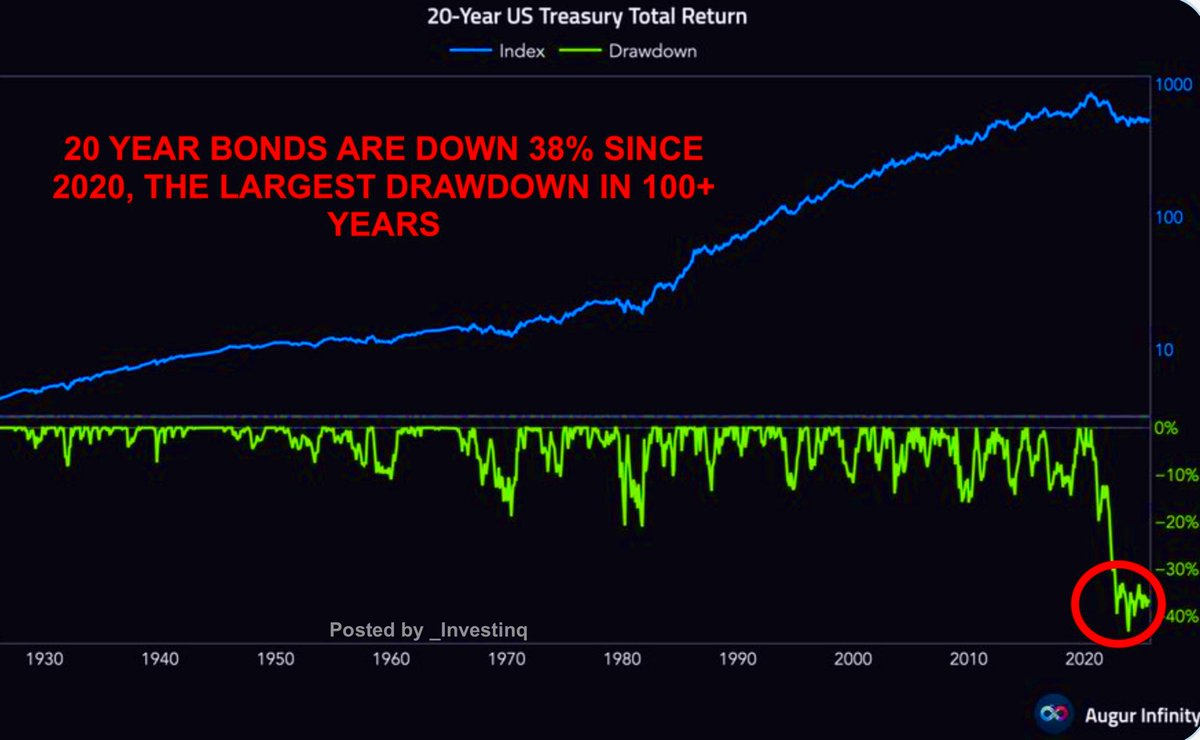

There are three main flavors of Treasuries.

• Bills: Short-term. Mature in less than 1 year.

• Notes: Medium-term. Mature in 2–10 years.

• Bonds: Long-term. Mature in 20–30 years.

Think of them as short, medium, and long loans.

• Bills: Short-term. Mature in less than 1 year.

• Notes: Medium-term. Mature in 2–10 years.

• Bonds: Long-term. Mature in 20–30 years.

Think of them as short, medium, and long loans.

Normally, the U.S. spreads borrowing across all three buckets.

Some debt matures quickly. Some comes due in a decade. Some doesn’t have to be paid back for 30 years.

That mix spreads out risk and stabilizes funding.

Some debt matures quickly. Some comes due in a decade. Some doesn’t have to be paid back for 30 years.

That mix spreads out risk and stabilizes funding.

But right now, the U.S. is leaning very heavily on bills.

Why? Because bills are cheaper today.

Imagine choosing between a 30-year fixed mortgage at 7% versus an adjustable one that resets every month at 4.2%. Treasury picked the adjustable mortgage.

Why? Because bills are cheaper today.

Imagine choosing between a 30-year fixed mortgage at 7% versus an adjustable one that resets every month at 4.2%. Treasury picked the adjustable mortgage.

This strategy saves money in the short run.

But it creates something called rollover risk. Bills mature fast. That means the government has to refinance constantly.

If rates fall, that’s good news. If rates rise, the pain hits immediately.

But it creates something called rollover risk. Bills mature fast. That means the government has to refinance constantly.

If rates fall, that’s good news. If rates rise, the pain hits immediately.

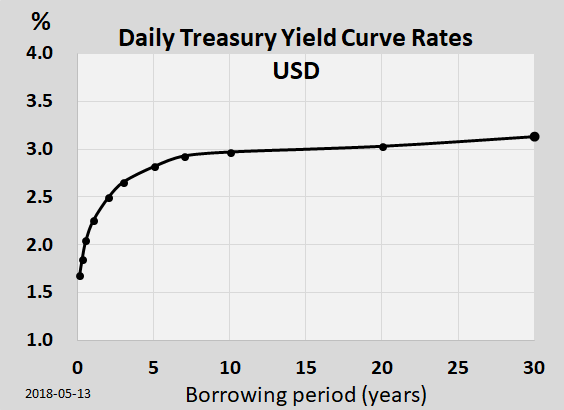

Now let’s decode the yield curve. The yield curve is just a graph.

On the left, it shows interest rates on short-term Treasuries like 1-month bills. On the right, it shows rates on long-term Treasuries like 30-year bonds.

The line connecting them is the curve.

On the left, it shows interest rates on short-term Treasuries like 1-month bills. On the right, it shows rates on long-term Treasuries like 30-year bonds.

The line connecting them is the curve.

Normally, the yield curve slopes upward. That’s because lending for longer is riskier.

Investors usually demand more interest to lock money away for decades.

So under normal conditions, 30-year bonds should pay more than 1-month bills.

Investors usually demand more interest to lock money away for decades.

So under normal conditions, 30-year bonds should pay more than 1-month bills.

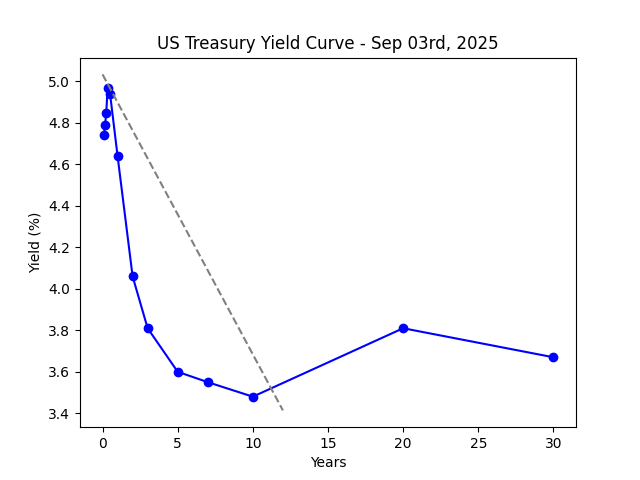

But today the curve is weird.

Short-term yields are very high because Treasury keeps flooding the market with bills. Long-term yields are lower because Treasury is buying back 10–30 year bonds, reducing their supply.

This artificially flattens the curve.

Short-term yields are very high because Treasury keeps flooding the market with bills. Long-term yields are lower because Treasury is buying back 10–30 year bonds, reducing their supply.

This artificially flattens the curve.

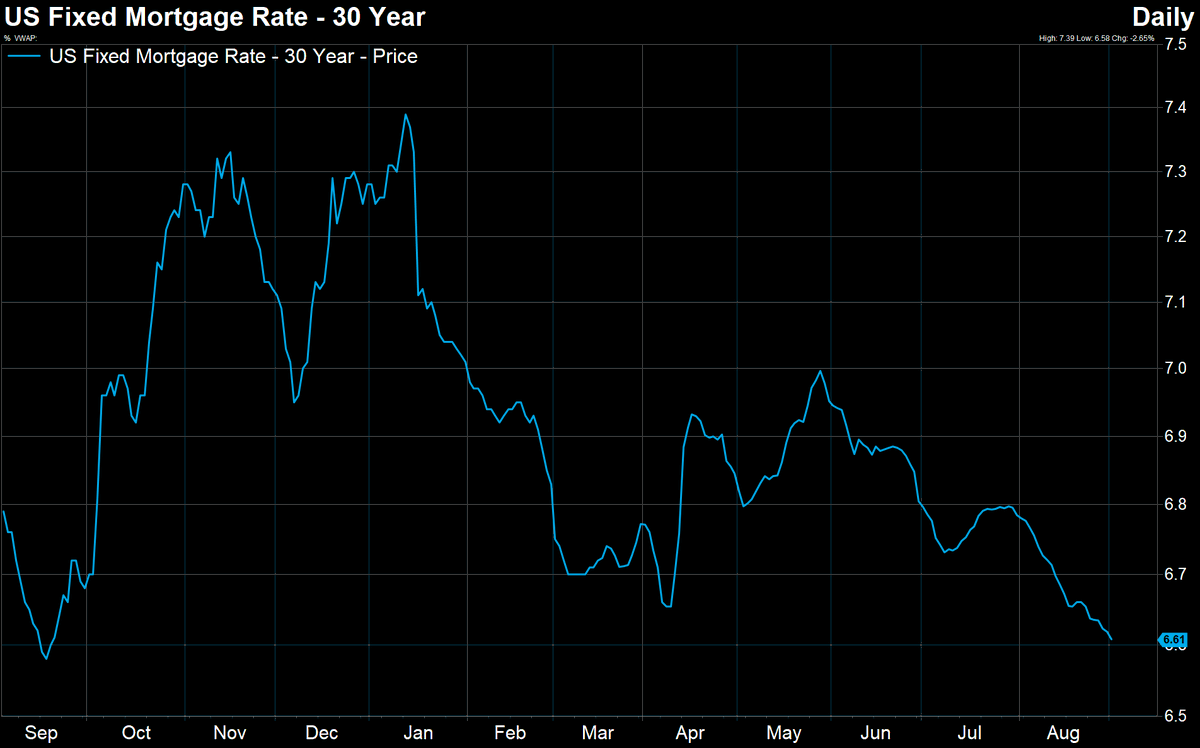

Why does that matter? Because the yield curve influences almost everything in the economy.

Mortgages. Car loans. Corporate debt.

If the curve bends unnaturally, it sends ripple effects into financial markets and household budgets.

Mortgages. Car loans. Corporate debt.

If the curve bends unnaturally, it sends ripple effects into financial markets and household budgets.

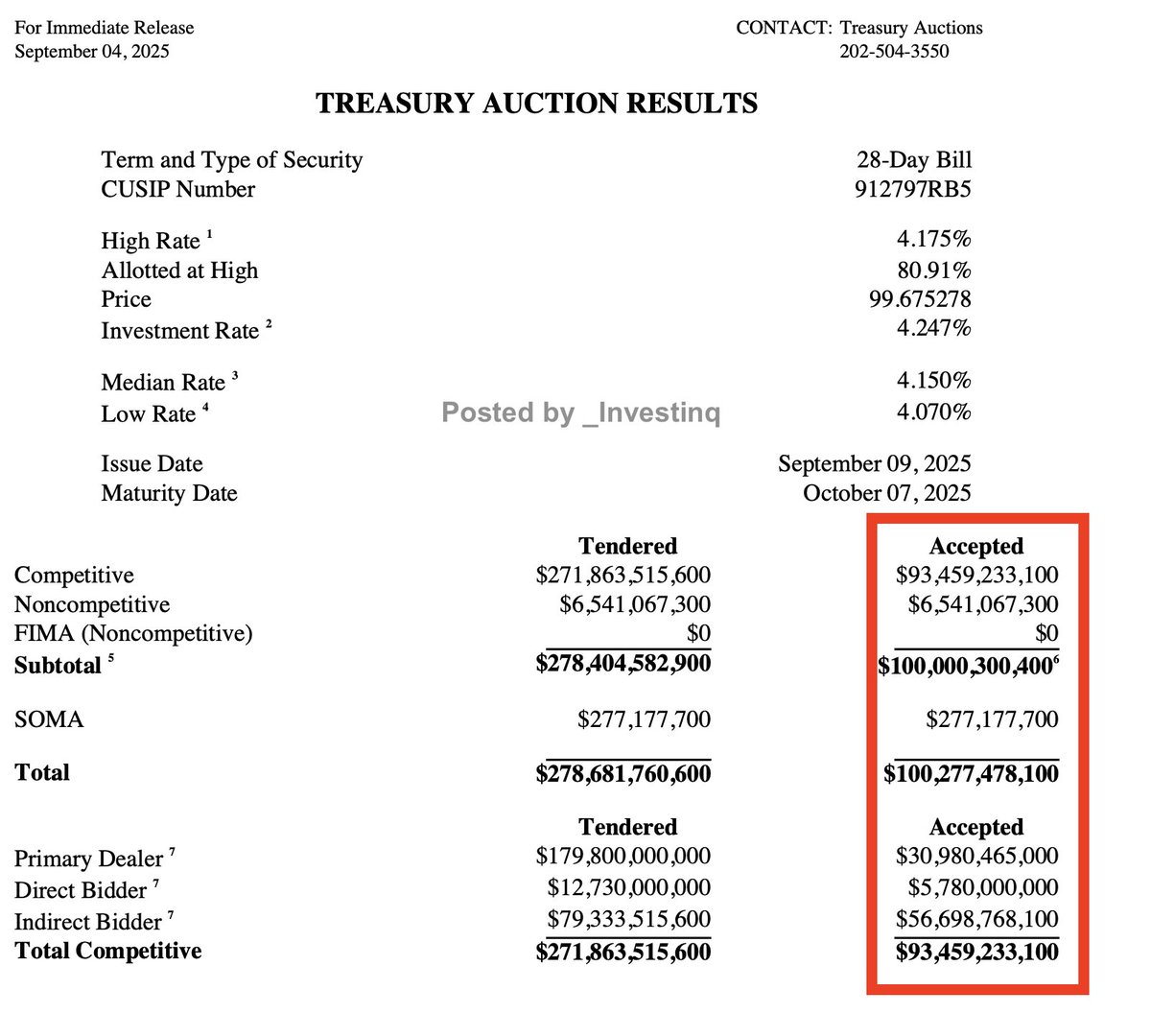

Back to the record $100B auction.

Investors offered $271.86B. Treasury accepted $93.46B.

That’s a bid-to-cover ratio of 2.9×, nearly 3 times more demand than supply. The stop-out yield, or winning interest rate, was 4.175%.

Investors offered $271.86B. Treasury accepted $93.46B.

That’s a bid-to-cover ratio of 2.9×, nearly 3 times more demand than supply. The stop-out yield, or winning interest rate, was 4.175%.

At that yield, 80.91% of bids were filled. The range was tight: 4.07% low, 4.15% median, 4.175% high.

Investors crowded at the stop. That shows strong, concentrated demand.

Everyone wanted in at nearly the same price.

Investors crowded at the stop. That shows strong, concentrated demand.

Everyone wanted in at nearly the same price.

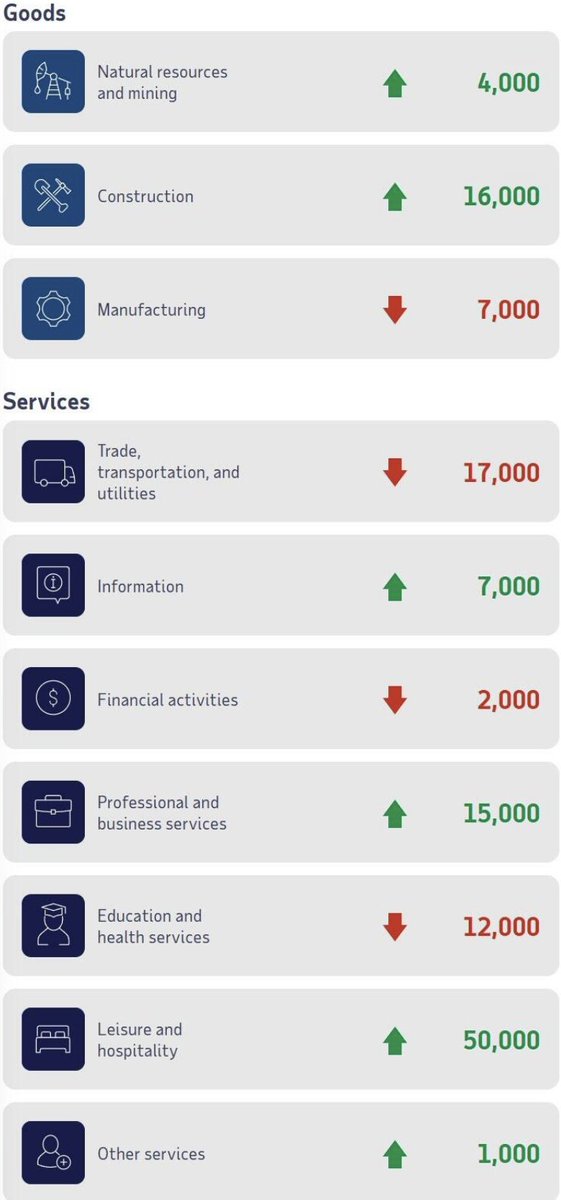

Who bought?

• Indirect bidders: foreign buyers, pensions, money market funds took about 61%.

• Primary dealers: the big banks required to absorb leftovers took 33%.

• Direct bidders: smaller asset managers and corporates took 6%.

This wasn’t weak demand. It was real.

• Indirect bidders: foreign buyers, pensions, money market funds took about 61%.

• Primary dealers: the big banks required to absorb leftovers took 33%.

• Direct bidders: smaller asset managers and corporates took 6%.

This wasn’t weak demand. It was real.

Bills are also the government’s shock absorber. Unlike long bonds, which are scheduled, bill sizes can change weekly.

That lets Treasury adjust quickly to manage its cash balance, the Treasury General Account (TGA).

Think of the TGA as Uncle Sam’s checking account.

That lets Treasury adjust quickly to manage its cash balance, the Treasury General Account (TGA).

Think of the TGA as Uncle Sam’s checking account.

The TGA holds tax revenues, spending, and cash from debt auctions. It’s housed at the Federal Reserve.

If the balance falls too low, Treasury issues more bills. If it rises too high, they issue fewer.

Bills make this account easy to manage.

If the balance falls too low, Treasury issues more bills. If it rises too high, they issue fewer.

Bills make this account easy to manage.

But again, the catch is rollover risk. Bills mature in weeks or months. That means refinancing constantly.

It’s like a family paying off one credit card with another.

As long as lenders keep lending, you’re fine. If they don’t, trouble starts fast.

It’s like a family paying off one credit card with another.

As long as lenders keep lending, you’re fine. If they don’t, trouble starts fast.

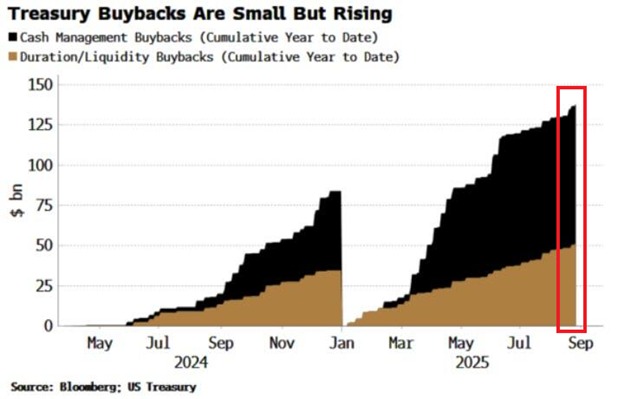

To balance things, Treasury has started buying back long bonds.

They sell short-term bills to raise cash. Then they use that cash to buy back 10- to 30-year bonds already in circulation.

That reduces long-end supply.

They sell short-term bills to raise cash. Then they use that cash to buy back 10- to 30-year bonds already in circulation.

That reduces long-end supply.

When supply falls, bond prices rise and when bond prices rise, yields fall.

That means Treasury is pushing down long-term borrowing costs.

This matters for mortgages, student loans, and corporate financing, anything linked to long-term rates.

That means Treasury is pushing down long-term borrowing costs.

This matters for mortgages, student loans, and corporate financing, anything linked to long-term rates.

Why would they want long yields lower? Because high long-term rates can choke the economy.

If mortgages cost 8%, housing slows. If companies can’t borrow cheaply, expansion freezes.

Lower long yields keep financial conditions looser.

If mortgages cost 8%, housing slows. If companies can’t borrow cheaply, expansion freezes.

Lower long yields keep financial conditions looser.

This also changes duration. Duration measures how sensitive a bond is to interest rate moves.

A 30-year bond has high duration, it swings when rates shift. A 4-week bill barely budges.

By swapping bonds for bills, Treasury shortens the system’s exposure.

A 30-year bond has high duration, it swings when rates shift. A 4-week bill barely budges.

By swapping bonds for bills, Treasury shortens the system’s exposure.

Some analysts call this “Yield Curve Control lite.”

True Yield Curve Control means setting a hard cap on yields and promising to buy unlimited bonds to enforce it.

Japan did this for years. The U.S. isn’t that explicit but by nudging supply, it’s steering outcomes.

True Yield Curve Control means setting a hard cap on yields and promising to buy unlimited bonds to enforce it.

Japan did this for years. The U.S. isn’t that explicit but by nudging supply, it’s steering outcomes.

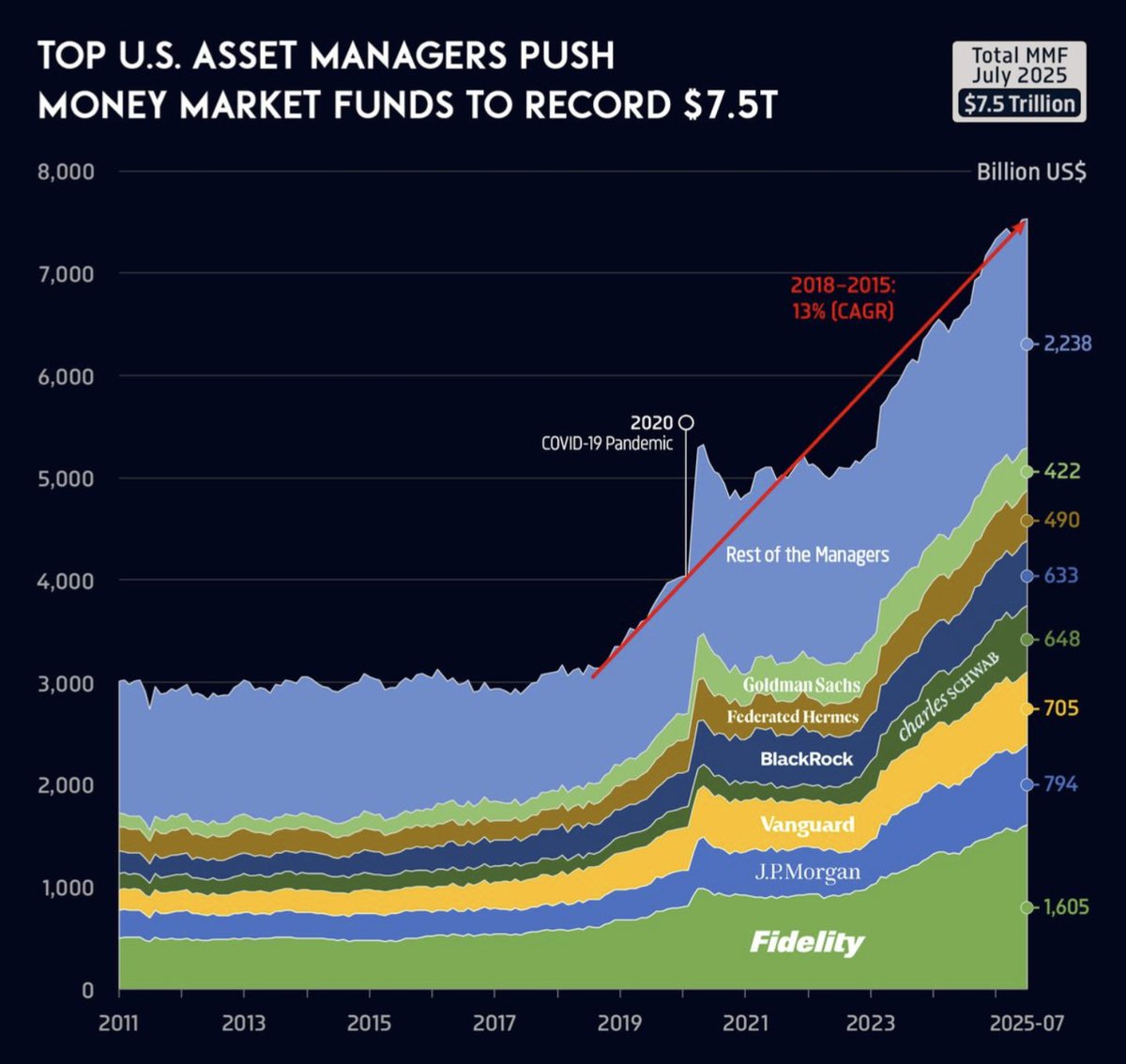

Who’s buying all these bills? First: money market funds (MMFs).

These are giant investment vehicles that hold trillions in ultra-safe assets.

Right now, they manage about $7.5 trillion. And recently, they’ve been pouring into bills.

These are giant investment vehicles that hold trillions in ultra-safe assets.

Right now, they manage about $7.5 trillion. And recently, they’ve been pouring into bills.

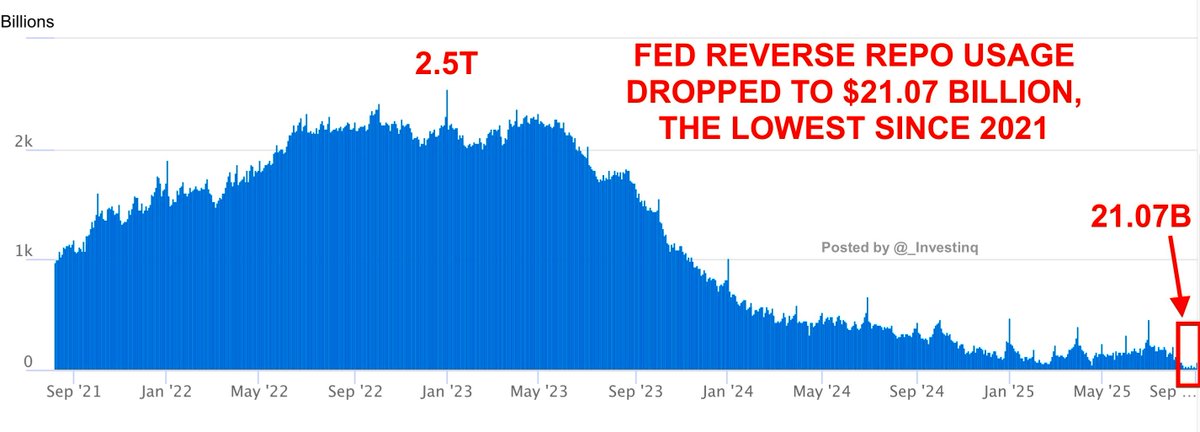

Why? Because bills yield slightly more than the Fed’s overnight reverse repo facility (RRP).

Think of RRP as the Fed’s overnight savings account.

When bills pay even a fraction more, funds shift out of the Fed and into Treasury auctions.

Think of RRP as the Fed’s overnight savings account.

When bills pay even a fraction more, funds shift out of the Fed and into Treasury auctions.

That tiny spread is powerful.If RRP pays 5.3% and bills pay 5.35%, it doesn’t sound like much.

But on trillions of dollars, that tiny pickup sends hundreds of billions into bills.

It’s like moving your savings from a 5.3% bank to a 5.35% bank, only at global scale.

But on trillions of dollars, that tiny pickup sends hundreds of billions into bills.

It’s like moving your savings from a 5.3% bank to a 5.35% bank, only at global scale.

MMFs have also stretched their weighted average maturity (WAM).

That’s the average length of the securities they hold. Right now it’s near 40 days, close to a record.

That shows they’re comfortable holding longer bills. This helps Treasury keep issuing without breaking demand.

That’s the average length of the securities they hold. Right now it’s near 40 days, close to a record.

That shows they’re comfortable holding longer bills. This helps Treasury keep issuing without breaking demand.

The second surprising buyer: crypto.

Stablecoins like USDT and USDC are digital tokens pegged to the U.S. dollar.

To maintain their peg, issuers hold reserves and increasingly, those reserves are T-bills.

Stablecoins like USDT and USDC are digital tokens pegged to the U.S. dollar.

To maintain their peg, issuers hold reserves and increasingly, those reserves are T-bills.

Today, stablecoins hold over $160 billion in bills. That’s more than some foreign governments.

Every new token minted = more T-bill demand.

It means crypto is now directly financing U.S. government debt.

Every new token minted = more T-bill demand.

It means crypto is now directly financing U.S. government debt.

But this creates fragility.

If a stablecoin faced redemptions, a hack, or regulatory freeze, billions of T-bills could be dumped instantly.

Which maturities would go first? The shortest ones, the same bills Treasury relies on most.

If a stablecoin faced redemptions, a hack, or regulatory freeze, billions of T-bills could be dumped instantly.

Which maturities would go first? The shortest ones, the same bills Treasury relies on most.

For now, plumbing looks stable. RRP balances are at multi-year lows, showing cash moved into bills.

Repo markets where banks borrow against Treasuries overnight are smooth.

But quarter-ends always bring tension.

Repo markets where banks borrow against Treasuries overnight are smooth.

But quarter-ends always bring tension.

Meanwhile, the Fed itself is running Quantitative Tightening (QT).

QT means letting bonds mature without reinvesting. That adds more long-term debt back into the market.

Treasury offsets this by issuing more bills and retiring long bonds.

QT means letting bonds mature without reinvesting. That adds more long-term debt back into the market.

Treasury offsets this by issuing more bills and retiring long bonds.

Risks to watch:

• Bills rising above 20% of debt for too long rollover risk grows.

• Auctions “tailing” weak demand forces yields higher.

• Indirect demand falling foreign and fund buyers step back.

• Repo spreads widening funding stress builds.

• Bills rising above 20% of debt for too long rollover risk grows.

• Auctions “tailing” weak demand forces yields higher.

• Indirect demand falling foreign and fund buyers step back.

• Repo spreads widening funding stress builds.

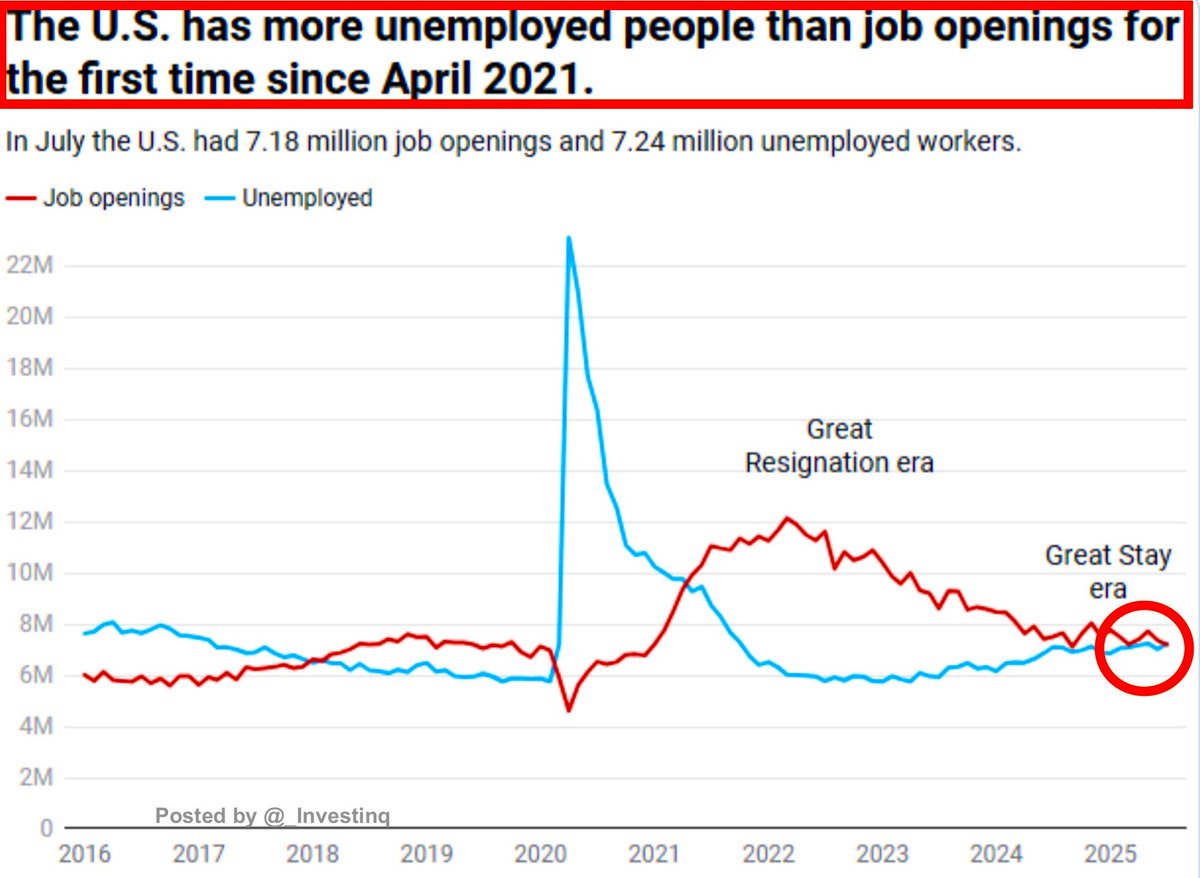

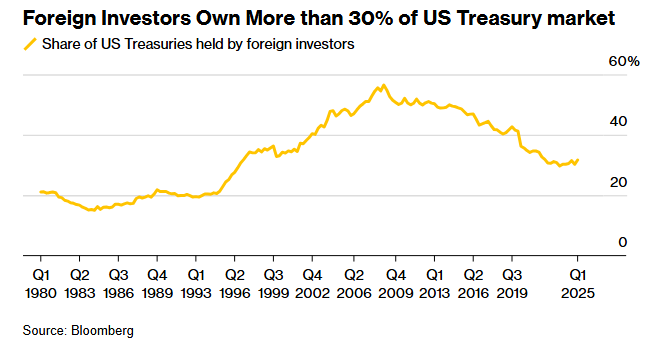

International flows matter too. In 2008, foreigners held over half of U.S. debt. Today, it’s closer to 30%.

Japan faces expensive currency hedges. China and Gulf states are buying less.

That leaves U.S. funds and even crypto to fill the gap.

Japan faces expensive currency hedges. China and Gulf states are buying less.

That leaves U.S. funds and even crypto to fill the gap.

The bottom line: The U.S. is relying on short-term bills more than ever.

It’s buying back long bonds to keep long-term yields low. It’s leaning on money funds and crypto to fund auctions.

The surface looks calm, but rollover risk keeps growing beneath it.

It’s buying back long bonds to keep long-term yields low. It’s leaning on money funds and crypto to fund auctions.

The surface looks calm, but rollover risk keeps growing beneath it.

If you found these insights valuable: Sign up for my FREE newsletter! thestockmarket.news

I hope you've found this thread helpful.

Follow me @_Investinq for more.

Like/Repost the quote below if you can:

Follow me @_Investinq for more.

Like/Repost the quote below if you can:

https://x.com/_investinq/status/1963700492724318718?s=46

@VladTheInflator @FinanceLancelot @StealthQE4

If you want to learn more about the Reverse Repo that was mentioned in this thread, here you go!

https://x.com/_investinq/status/1962985792118124931?s=46

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh