Although it's rarely expressed in outright terms, people often use a very simple heuristic when solving fashion problems: they wish to look rich, which is often disguised as "respectable."

I will show you why this rarely leads to good outfits. 🧵

I will show you why this rarely leads to good outfits. 🧵

In 1902, German sociologist Georg Simmel neatly summed up fashion in an essay titled "On Fashion." Fashion, he asserted was simply a game of imitation in which people copy their "social betters." This causes the upper classes to move on, so as to distinguish themselves.

He was right. And his theory explains why Edward VIII, the Duke of Windsor, was the most influential menswear figure in the early 20th century. By virtue of his position and taste, he popularized soft collars, belted trousers, cuffs, Fair Isle sweaters, and all sorts of things.

However, the spread of liberal-democratic norms in the 20th century changed this simple dynamic. The rise of pro-worker movements, racial and sexual equality, and youth countercultures meant that upper-middle classes were no longer the primary source of fashion direction.

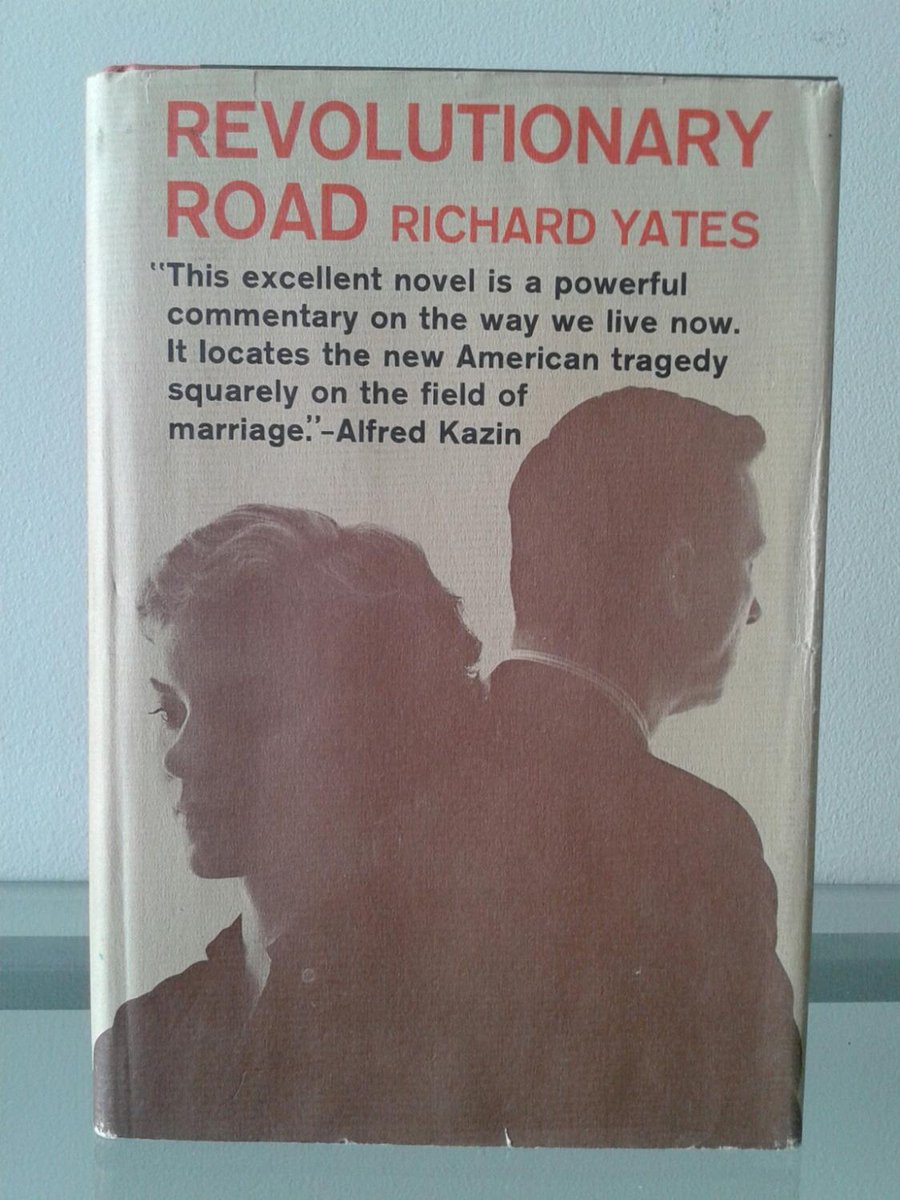

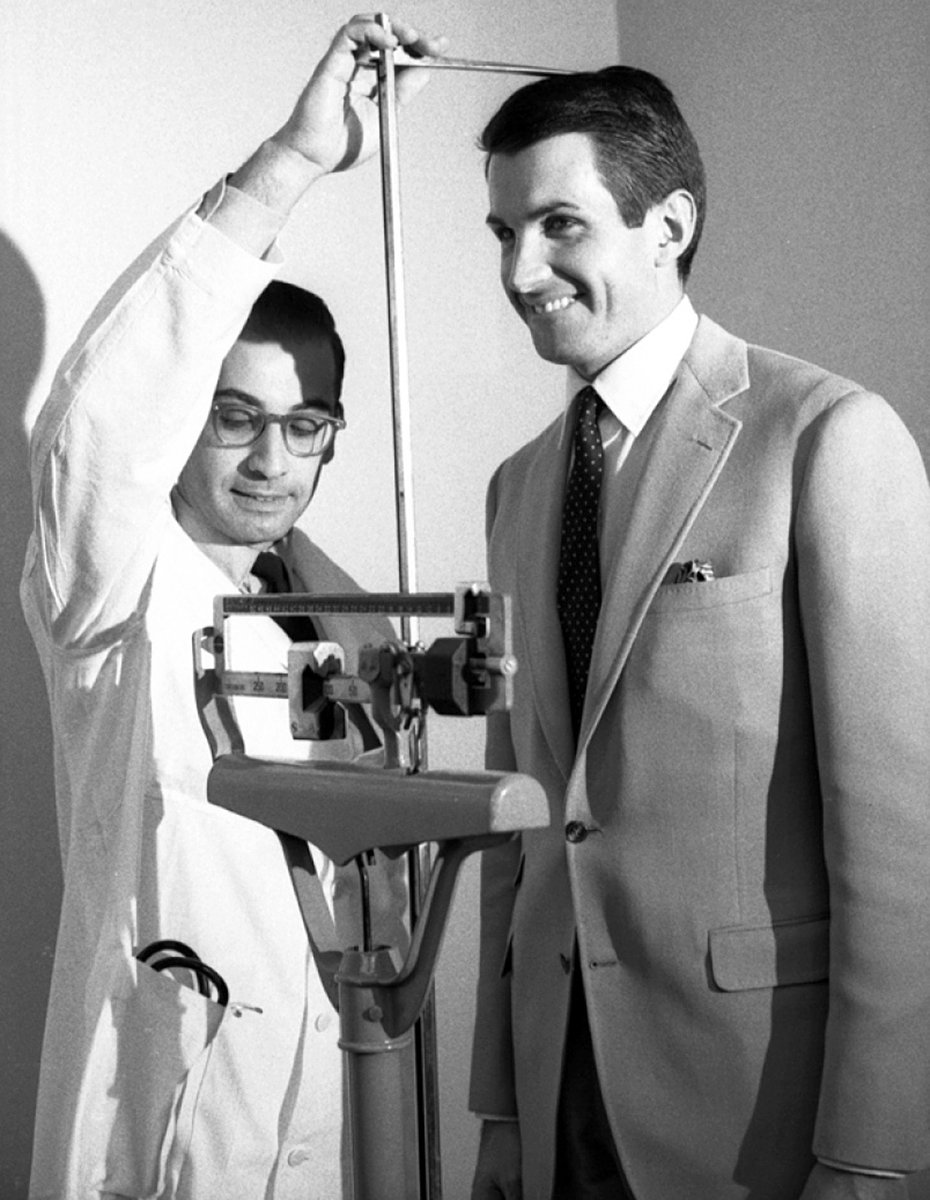

We see this in the most famous post-war film titled after the bourgeoise uniform: The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1956). Gregory Peck plays a company man struggling with the conformity of a white-collar life. We also see it in books, such as Richard Yates's Revolutionary Road.

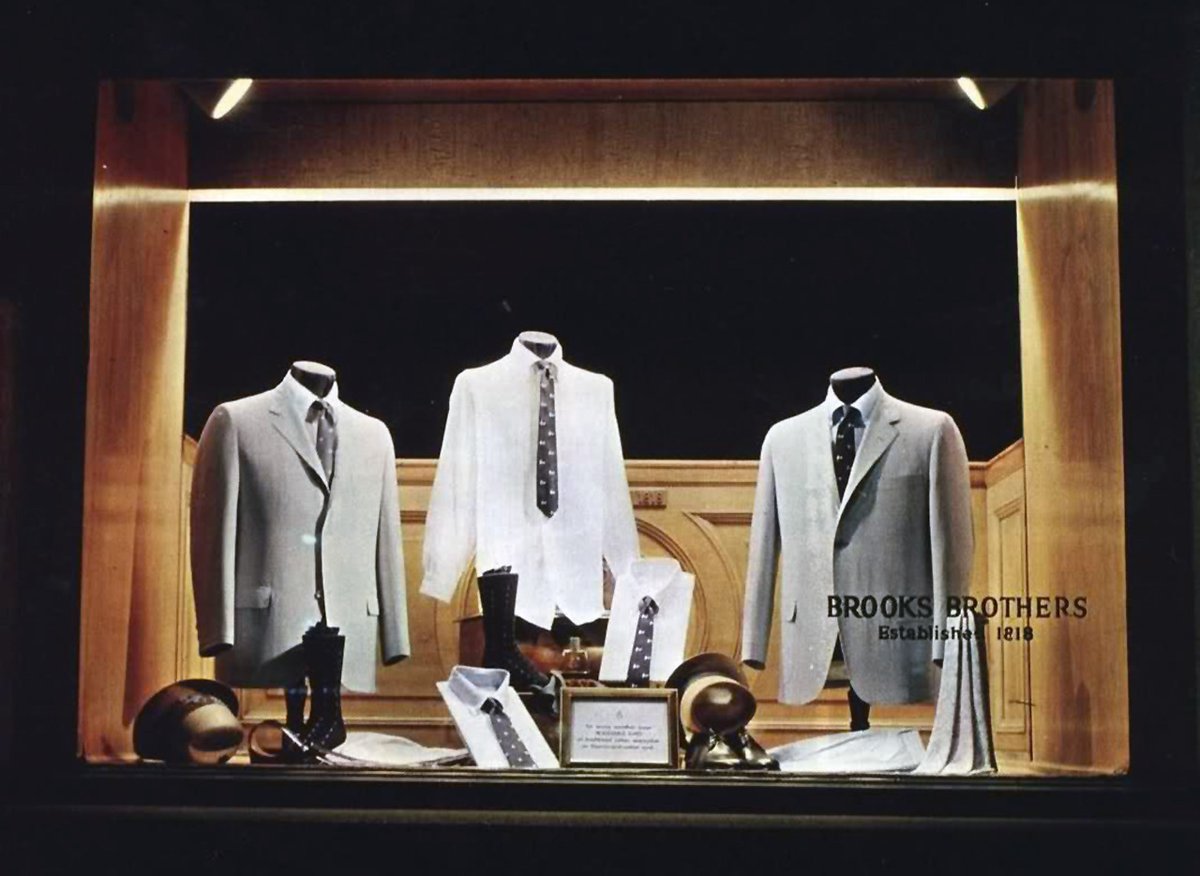

In 1958, the New York Times held a panel on what people thought of the Ivy League Look (e.g. navy blazer, oxford button down collar, gray flannel trousers). John Wood, then-President of Brooks Brothers, naturally said it signaled "conservative good taste."

Others were less positive. One woman described wearers as "Madison Avenue lemmings enslaved to conformity." Another said it is a "sorry testimony to the fact that individuality is something to which most men have ceased to aspire." They look like a "pickled undergraduates."

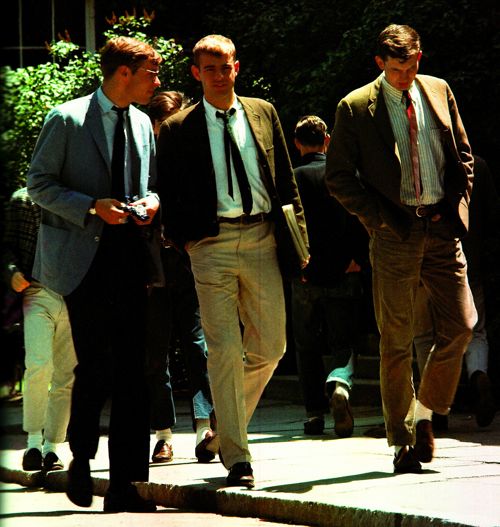

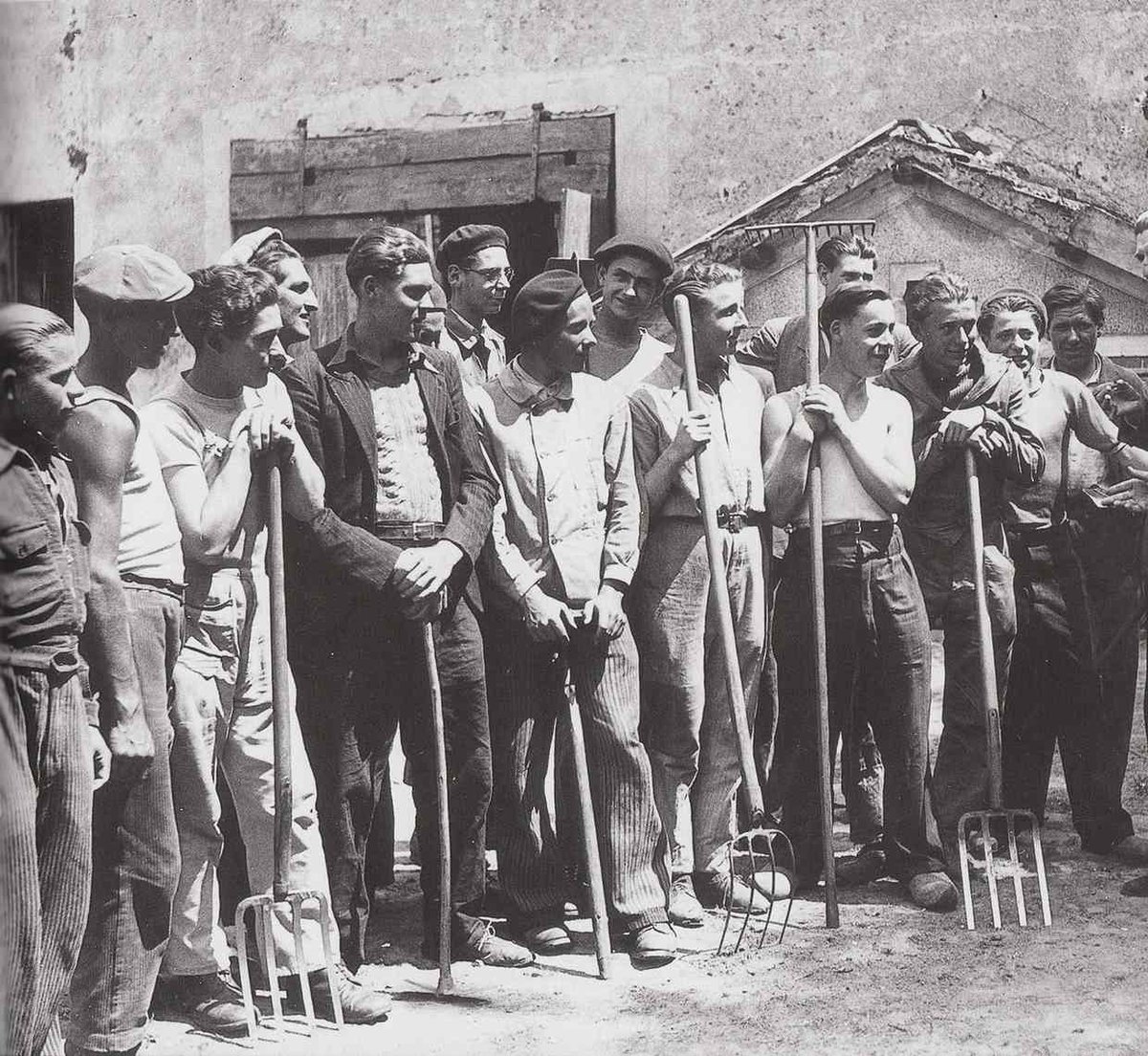

They were right in one regard: the Ivy Look symbolized conformity to bourgeoise life. The wearers were often veterans who returned home from the trenches of Europe, got a free college eduction through the GI Bill, graduated to corporate jobs, and raised a nuclear family.

What they saw as sad conformity, others saw as success.

But the critics were wrong in a different sense: it was not a bad look. Since a tailored jacket is made from multiple layers of haircloth, canvas, and padding, it confers a certain silhouette no other style can achieve.

But the critics were wrong in a different sense: it was not a bad look. Since a tailored jacket is made from multiple layers of haircloth, canvas, and padding, it confers a certain silhouette no other style can achieve.

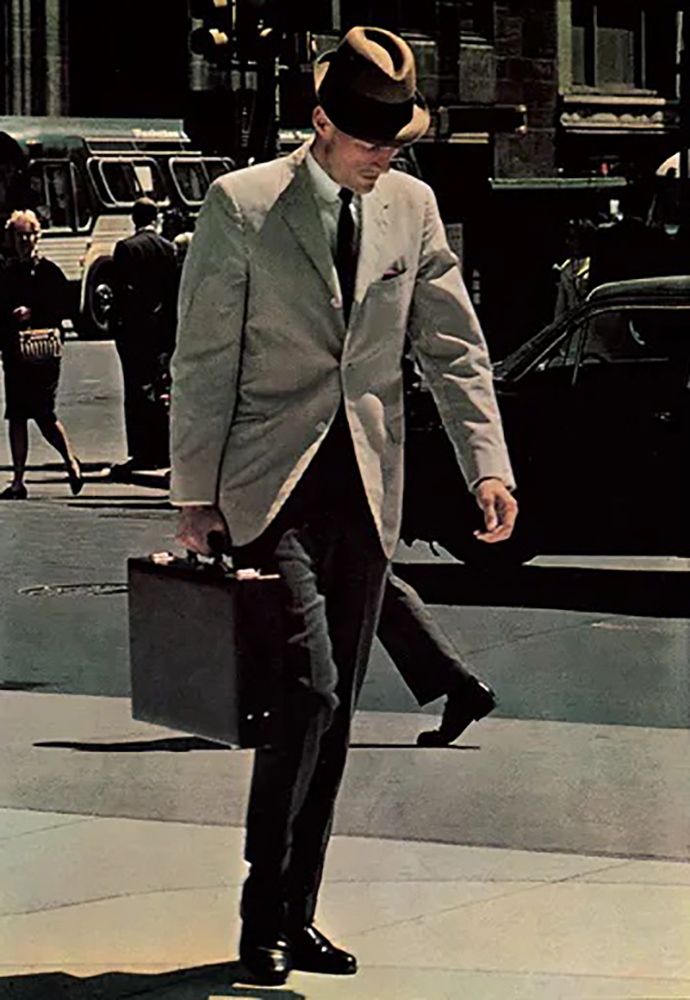

This is how we get these beautiful silhouettes: v-shaped torso set on columnar legs with curvy details, such as the lapel that blooms out of the buttoning point. When combined with different fabrics, shirts, and ties, it can be a quite good look.

The problem is that, over time, the bourgeoise slowly shed this uniform. First they ditched the jacket that confers the flattering silhouette. Then necktie, relieving it of its symbolic labor (and losing more color). Some even replaced the dress shirt and attendant dress shoe.

The typical bourgeoise uniform now consists of a pair of slim fit chinos, a pique cotton or technical fabric polo shirt that clings to the body, marshmallow shaped dress sneakers, and a five figure sports watch to show "you've made it."

The outfit is devoid of the silhouette that tailoring once conferred, relying instead only on class signifiers ("I am upper middle class"), a quality that was barely even respected in the immediate post-war years.

In his book Rebel Style, Bruce Boyer frames the mid-century culture wars in terms of clothes. Establishment types took to suits; anti-establishment types wore chambray shirts, leather motorcycle jackets, and engineer boots. This style was captured in the film The Wild One.

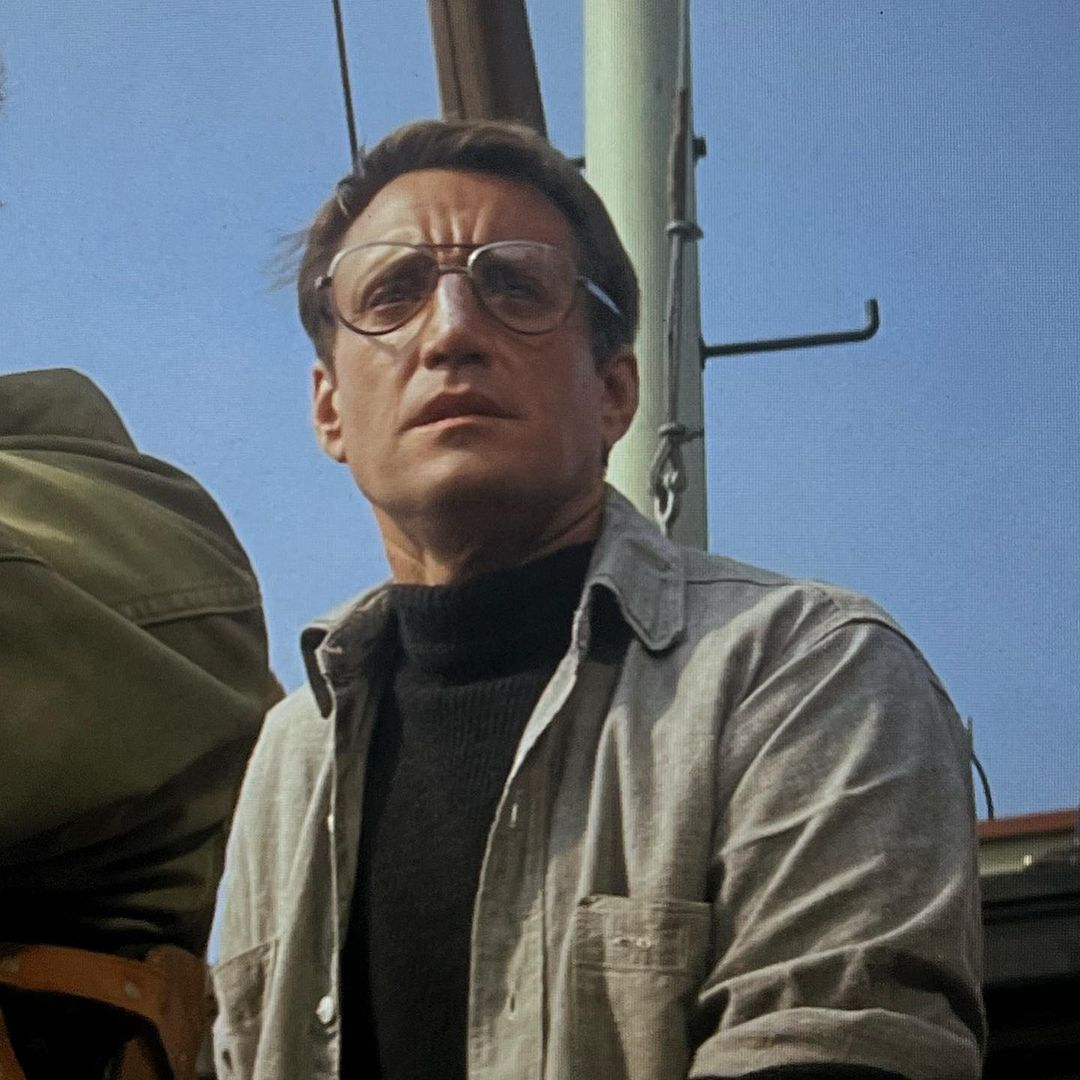

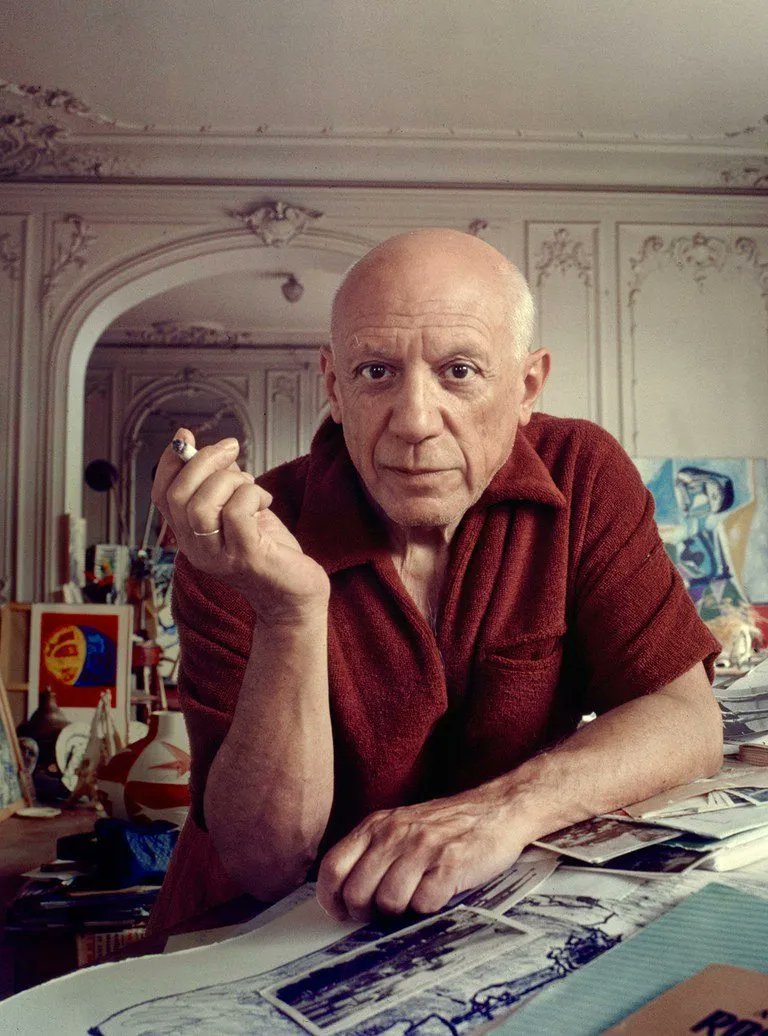

And it's true: the working class and countercultural types have always held some sway on fashion. The turtleneck, made sophisticated by Noel Coward, was originally a fisherman's knit before being taken up by writers, artists, and left-leaning intellectuals. That's why it's cool

But this dynamic went into full force after the war. Yes, wealthy people still shape fashion, but so do people without financial capital. This is why Justin Bieber dresses like someone who just got out of prison for making methamphetamine. He wants to look cool.

I should note that different people have different aims with fashion. Some people simply want to attract a mate, climb the corporate ladder, and achieve middle-class respectability. Thus, they will ape whatever the upper middle-class does, as they want to blend in.

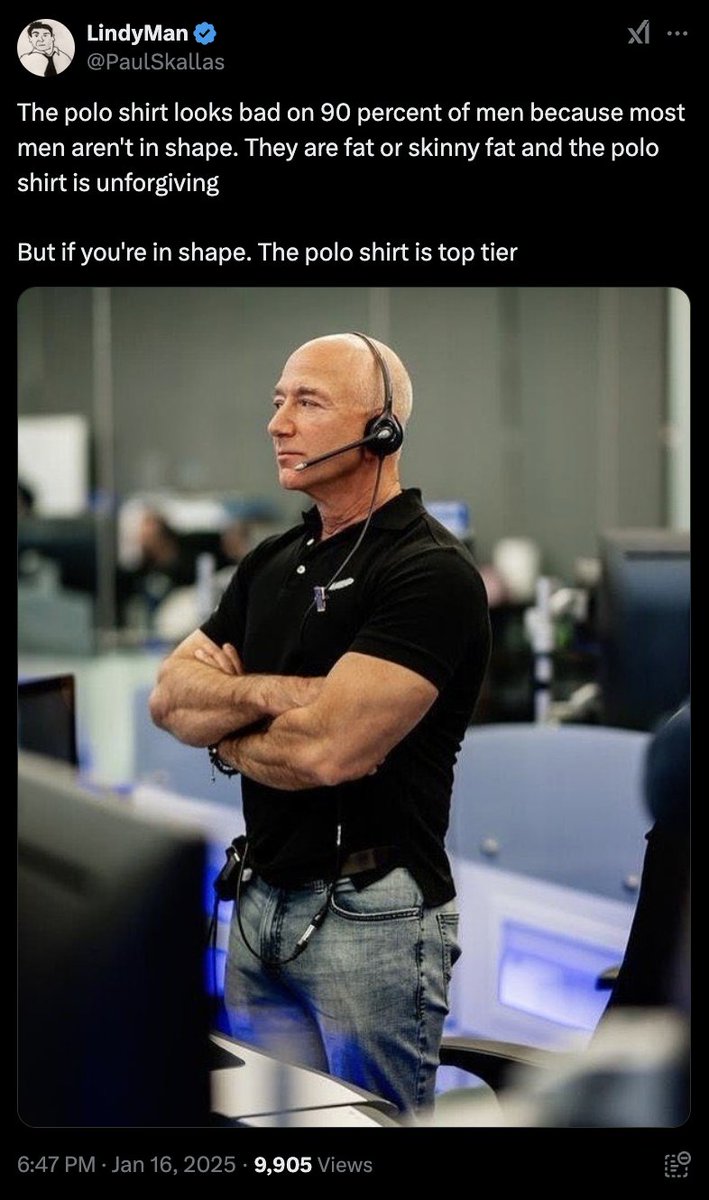

This is the perspective of people whose sole fashion advice is "work out" and "wear a polo."

I have no opinion on how to attract a mate, climb the social ladder, or achieve this success. So if that is your aim, my advice may not be for you.

I have no opinion on how to attract a mate, climb the social ladder, or achieve this success. So if that is your aim, my advice may not be for you.

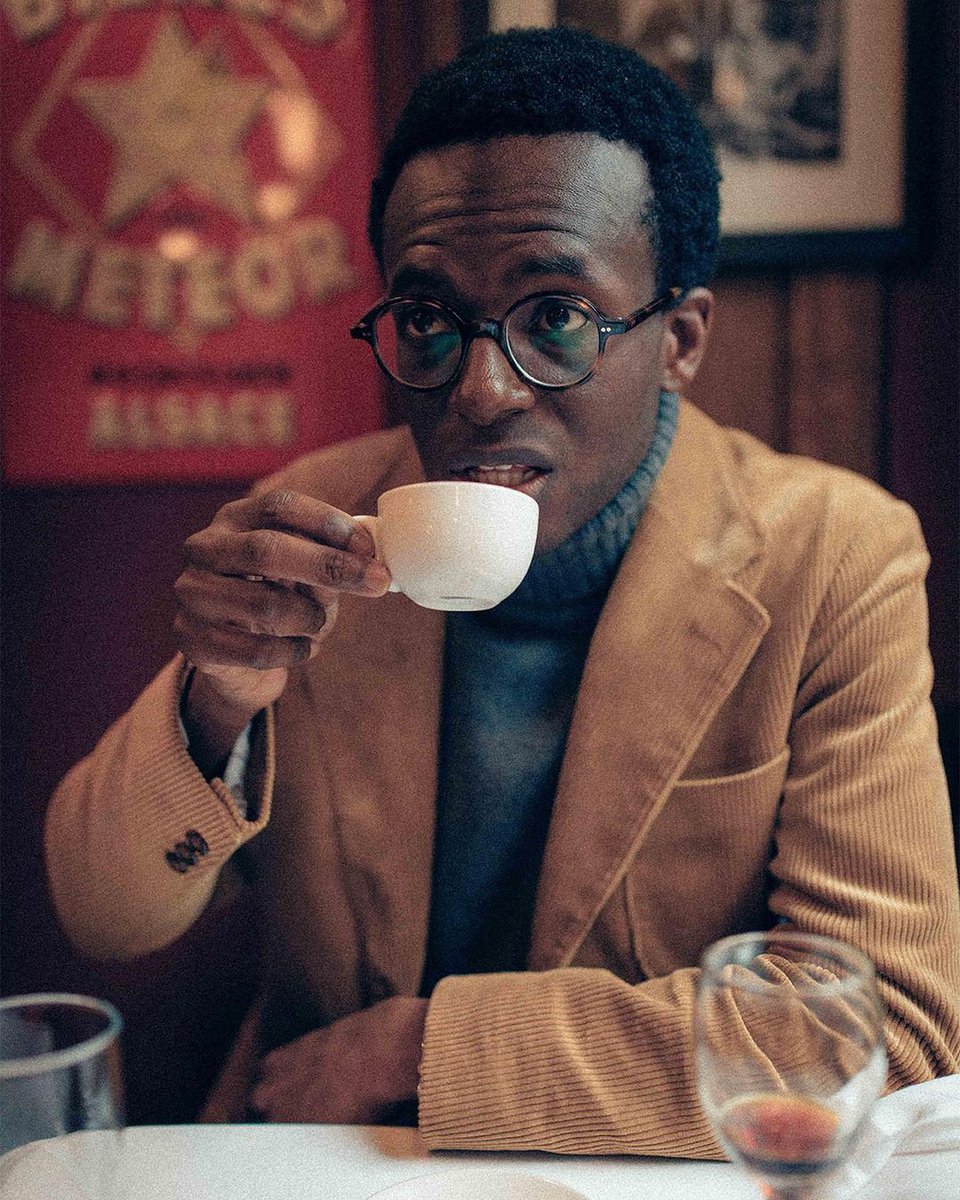

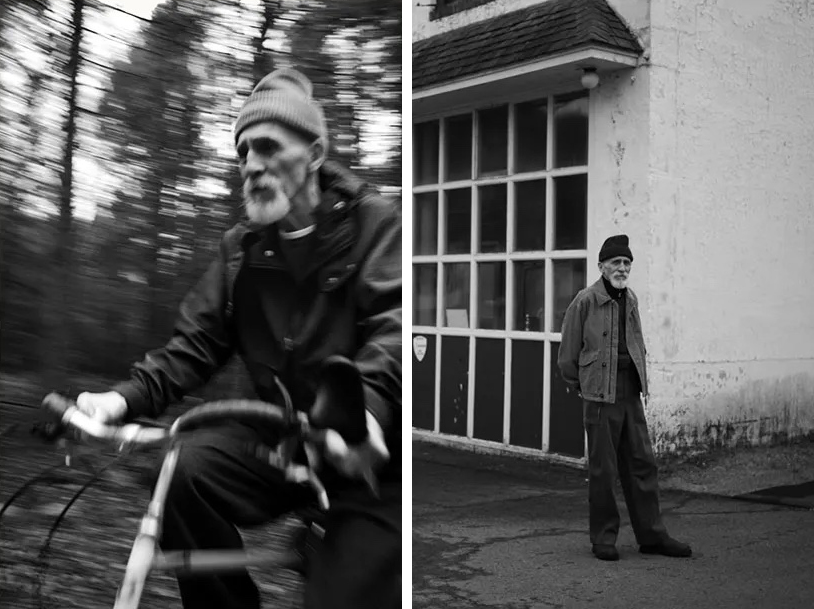

However, I do think that uniform lacks aesthetic appeal. It holds none of the shaping and tailoring of the mid-century look, nor the cultural capital of the artists, workers, or countercultural types. It's the most boring, vanilla bland aesthetic possible. This is better:

And so, I don't think "copy the bourgeoise" holds any real value anymore. They've lost their silhouette and the lifestyle was never that cool in the first place. If you want to dress casually outside of the suit, you have to look towards other social groups for inspiration.

There are lots of aesthetics that still hint at wealth, such as Lemaire, Auralee, Stoffa, and 7115 by Szek. But these things have a bit of sauce — a little something, something. A silhouette, texture, unique details. It's not the basic corporate uniform.

That's why, in my opinion, if you wear a polo, it has to have a little something: a bit of texture, a skipper collar, or tucked underneath a jacket. It can't be that "slim fit chino, golf polo, dress sneaker, fancy sports watch" look.

To me, this distinction marks one of the biggest differences in how people approach fashion. Sometimes I post outfits like these and someone will say "he looks homeless," as though not having a home automatically means an outfit is bad.

They assume the cultural supremacy of the wealthy. On the contrary, I think lots of aesthetics are legitimate, including those outside of the bourgeoisie. It's impossible for me to tell you what to wear outside of that business casual uniform bc I don't know your inspirations.

But I would say just be careful of whether you assume something is "good" just because it's worn by the upper middle classes. If your goal is to look like them, then great. But not everyone is trying to.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh