In the reading of the reader al-ʾAʿmaš (d. 148) already on verse 5 of al-Fātiḥah he recites something that no canonical reader does: he reads nistaʿīnu rather than nAstaʿīnu.

This is what Sibṭ al-Ḫayyāṭ (d. 541), but this is absent in other descriptions, what's going on? 🧵

This is what Sibṭ al-Ḫayyāṭ (d. 541), but this is absent in other descriptions, what's going on? 🧵

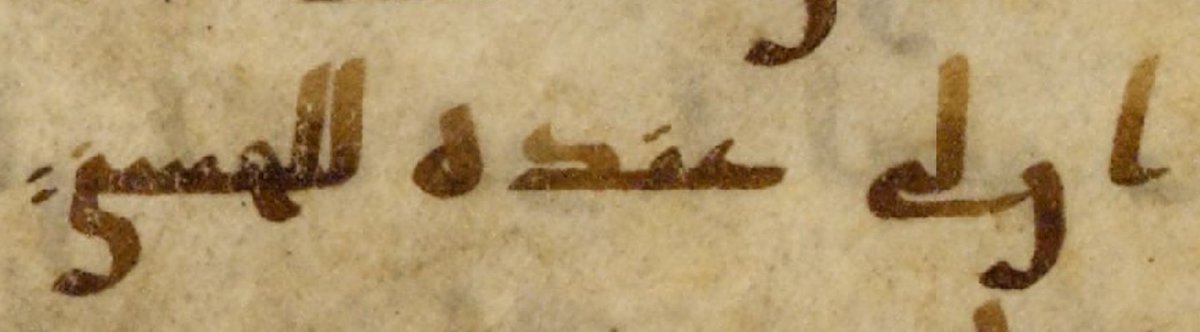

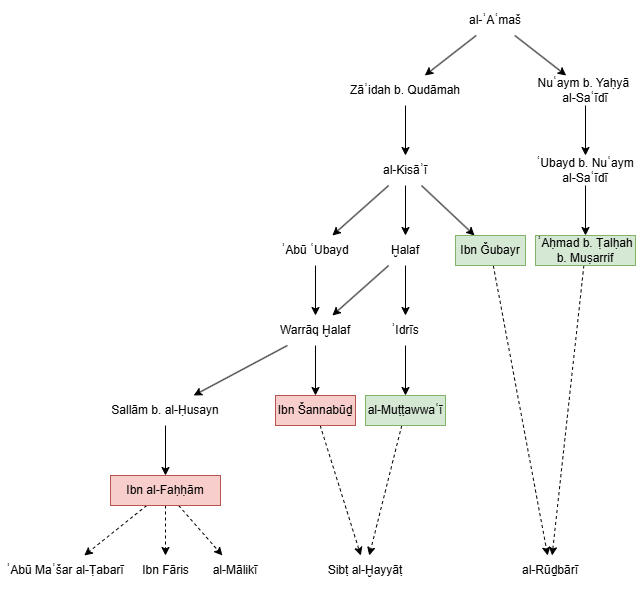

This is what Sibṭ al-Ḫayyāṭ says:

al-ʾAʿmaš recired in the path of al-Muṭṭawwaʿī "nistaʿīnu" with a kasrah on the first nūn, and it is likewise for the kasrah of the tāʾ in "tiʿlam", "tiʿṯaw", "tirkanū", "fa-timassakumu n-nāru" and what is like that.

al-ʾAʿmaš recired in the path of al-Muṭṭawwaʿī "nistaʿīnu" with a kasrah on the first nūn, and it is likewise for the kasrah of the tāʾ in "tiʿlam", "tiʿṯaw", "tirkanū", "fa-timassakumu n-nāru" and what is like that.

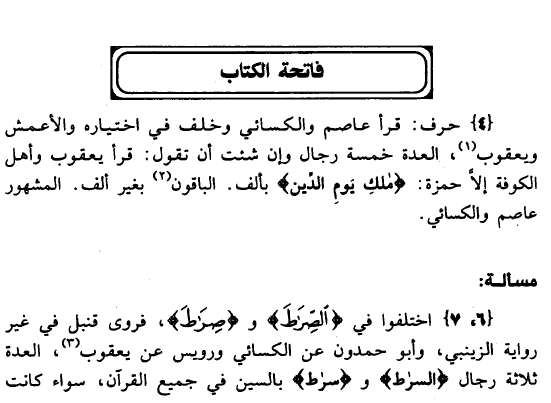

To Hebraists this distribution should look familiar: this clearly represents what they call the "Barth-Ginsberg Law". The prefix vowel of the verb is an /i/, whenever the stem vowel is an /a/. This is well-known among the medieval grammarians.

Since it is shared by Hebrew and Arabic, this must be the archaic situation and thus go back at least to the shared ancestor of Hebrew and Arabic: Central Semitic.

But most Quranic readers have innovated the /a/ vowel in the prefix. This is a Hijazi Arabic innovation.

But most Quranic readers have innovated the /a/ vowel in the prefix. This is a Hijazi Arabic innovation.

But in the wording of Sibṭ al-Ḫayyāṭ we can already see that this report for al-ʾAʿmaš is not unanimous: Sibṭ al-Ḫayyāṭ mentions it only for the path of al-Muṭṭawwaʿī, not for the other paths he has from him, that of al-Šannabūḏī from Ibn Šannabūḏ.

So which one is original to al-ʾAʿmaš's reading? How can we tell? To get more insight into this it is worthwhile chasing down other descriptions of al-ʾAʿmaš's reading in other works, and see what they report.

- al-Ḥasan b. Muḥammad al-Mālikī al-Baġdādī (d. 438):

No mention of Barth-Ginsberg.

- Ibn Fāris al-Ḫayyāṭ (d. 452): No mention.

- al-Huḏalī (d. 465): No mention.

- ʾAbū Maʿšar al-Ṭabarī (d. 478): No mention (no screenshot).

- al-Rūḏbārī (d. after 489): Mentions it!

No mention of Barth-Ginsberg.

- Ibn Fāris al-Ḫayyāṭ (d. 452): No mention.

- al-Huḏalī (d. 465): No mention.

- ʾAbū Maʿšar al-Ṭabarī (d. 478): No mention (no screenshot).

- al-Rūḏbārī (d. after 489): Mentions it!

By sheer number, the Barth-Ginsberg alternation attributed to al-ʾAʿmaš is in the minority 1.5 for (Sibṭ al-Ḫayyāṭ (al-Muṭṭawwaʿī) and al-Rūḏbārī) and 4.5 against (Sibṭ al-Ḫayyāṭ (al-Šannabūḏī), Ibn Fāris, al-Huḏalī, al-Ṭabarī). So is the attribution wrong?

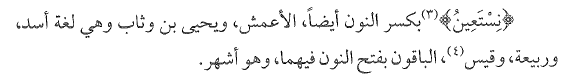

No! Here a majority rules approach is certainly *not* the way to go. What we need to look at is the transmission paths of these different authors. If we do so, we notice a *very* specific bottleneck for those that do not report Barth-Ginsberg for al-ʾAʿmaš.

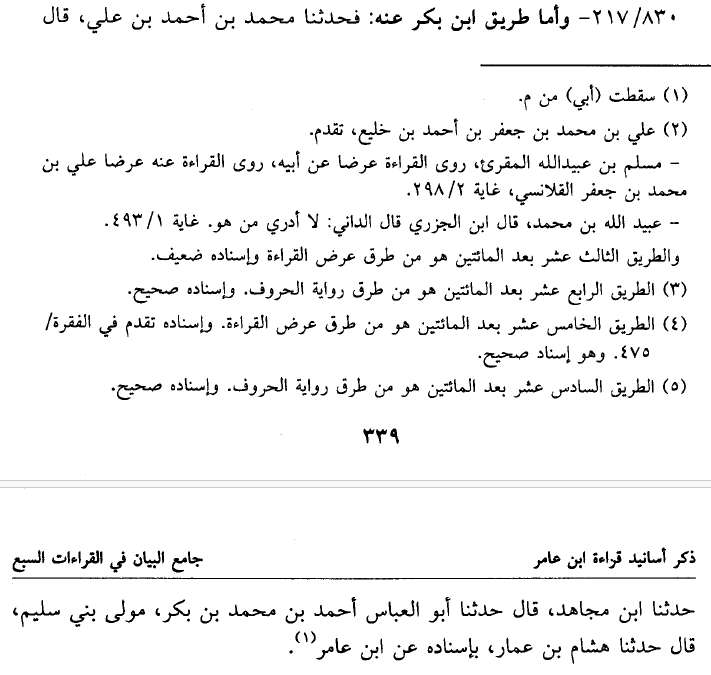

If we look at the ʾIsnāds that each of the sources have we see that three of our five sources all get their transmission of al-ʾAʿmaš through Ibn al-Faḥḥām.

None of them report the Barth-Ginsberg Law for him.

Sibṭ al-Ḫayyāt also doesn't in his Ibn Šannabūḏ path,

None of them report the Barth-Ginsberg Law for him.

Sibṭ al-Ḫayyāt also doesn't in his Ibn Šannabūḏ path,

These two tradents share a common link in Warrāq Ḫalaf (i.e. "Ḫalaf's copyist").

Transmission paths that don't go through Warrāq Ḫalaf, even the path that goes through Ḫalaf, all mention Barth-Ginsberg.

Warrāq Ḫalaf therefore must be the origin for this absence.

Transmission paths that don't go through Warrāq Ḫalaf, even the path that goes through Ḫalaf, all mention Barth-Ginsberg.

Warrāq Ḫalaf therefore must be the origin for this absence.

It is possible that he received this from ʾAbū ʿUbayd, and a conflicting report from Ḫalaf, and he decided -- for whatever reason -- to follow ʾAbū ʿUbayd's instruction rather than Ḫalaf's. But the reason that it promulgated in most transmissions is certainly his fault.

There is a slight fly in the ointment: al-Huḏalī (whom I didn't include in the chart) also traces his Isnād through Ibn Ǧubayr, and in fact along the exact same path as al-Rūḏbārī (through their shared teacher: al-ʾAhwāzī).

My best guess is that al-Huḏalī, whose book includes 50 (!) different readings simply forgot to include this one exceptional practice that is unique to al-ʾAʿmaš only. But I'd be happy to hear other solutions!

While it is of course unlikely that three people across three different paths would have spuriously attributed this unique Barth-Ginsberg alternation to al-ʾAʿmaš independently if it wasn't attributed to him. There is in fact even more information that this is right...

There are very strong indications that al-ʾAʿmaš's teacher, Yaḥyā b. al-Waṯṯāb likewise had the i-vowels in the prefixes of such verbs. While no full description of Ibn al-Waṯṯāb survives, we have a number of sources that attribute this to him. We saw 1 already: al-Rūḏbārī.

But even much earlier sources explicitly attribute this to him:

Ibn Ḫālawayh (d. 380) mentions it for lā tiqrabā

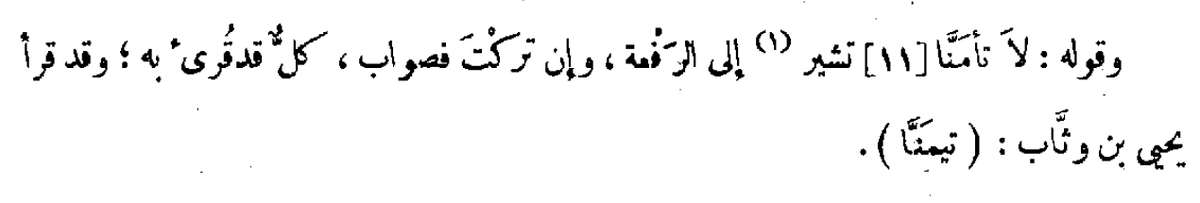

Al-Farrāʾ (d. 207) even reports it for him in places where this goes against the rasm (also reported by Ibn Ḫālawayh) such as in Q12:11 tīmannā/tiʾmannā.

Ibn Ḫālawayh (d. 380) mentions it for lā tiqrabā

Al-Farrāʾ (d. 207) even reports it for him in places where this goes against the rasm (also reported by Ibn Ḫālawayh) such as in Q12:11 tīmannā/tiʾmannā.

So while we lack the same in-depth reporting from Yaḥyā's reading, the surviving tidbits clearly indicate that this is a practice that al-ʾAʿmaš inherited from his teacher.

This case is an excellent example of how, by performing careful study of the paths and transmissions of a Quranic reading, you can figure out the original reading practice of a reader, even if you are confronted with competing reports.

A kind of ICQA "Isnād-cum-qirāʾah analysis"

A kind of ICQA "Isnād-cum-qirāʾah analysis"

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh