In October 2022, the activist investor Starboard Value bought 7% of a small provider of Data Center Solutions.

On month later, ChatGPT was released.

The Data Center market exploded, and the stock is up 12x in 2 years. A masterclass in activism investing (or market timing)🧵

1) Data Center and Vertiv Overview

2) Data Center Tailwinds

3) Lack of Urgency

4) Valuation Discount

5) Margin Opportunity

6) Multiple Opportunity

On month later, ChatGPT was released.

The Data Center market exploded, and the stock is up 12x in 2 years. A masterclass in activism investing (or market timing)🧵

1) Data Center and Vertiv Overview

2) Data Center Tailwinds

3) Lack of Urgency

4) Valuation Discount

5) Margin Opportunity

6) Multiple Opportunity

1) Data Center and Vertiv Overview

To understand Vertiv, you need to understand its end market data centers.

Google defines data center is a physical facility that houses computing and networking equipment, used to store, process, and distribute an organization's critical data and applications, essentially acting as a centralized location for managing large amounts of digital information.

Vertiv sells into some of the most attractive areas of the data center market including the racks (where the GPUs are placed), power supply, cooling systems, testing services, and software management

To understand Vertiv, you need to understand its end market data centers.

Google defines data center is a physical facility that houses computing and networking equipment, used to store, process, and distribute an organization's critical data and applications, essentially acting as a centralized location for managing large amounts of digital information.

Vertiv sells into some of the most attractive areas of the data center market including the racks (where the GPUs are placed), power supply, cooling systems, testing services, and software management

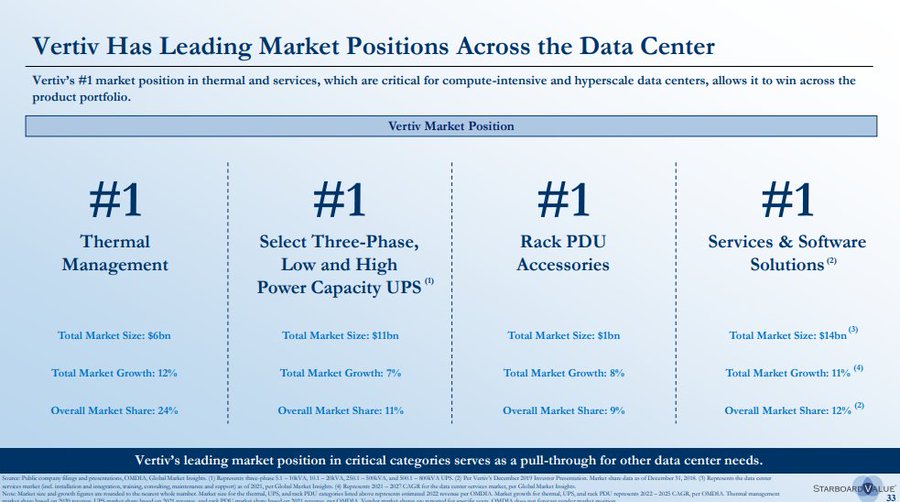

Vertiv Competitive Position

Vertiv dominates this market.

Vertiv’s #1 market position in thermal and services, which are critical for compute-intensive and hyperscale data centers, allows it to win across the product portfolio.

Vertiv’s leading market position in critical categories serves as a pull-through for other data center needs.

Vertiv dominates this market.

Vertiv’s #1 market position in thermal and services, which are critical for compute-intensive and hyperscale data centers, allows it to win across the product portfolio.

Vertiv’s leading market position in critical categories serves as a pull-through for other data center needs.

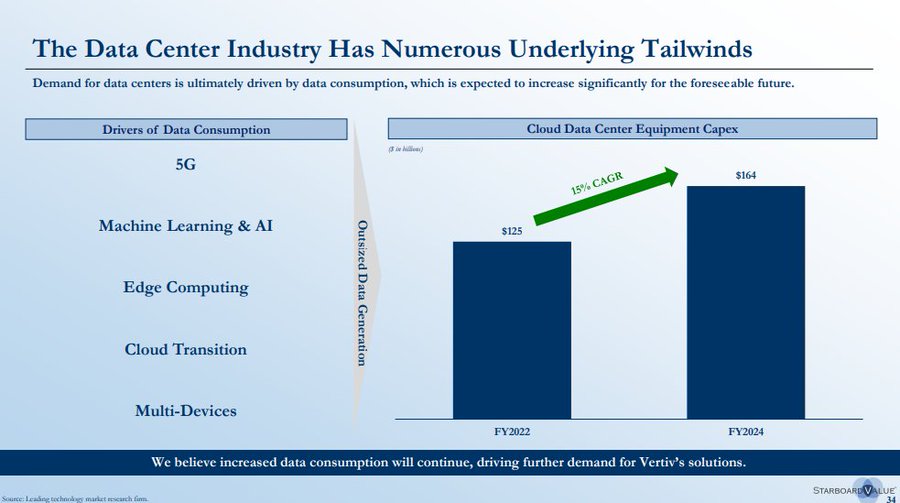

2) Data Center Tailwinds

This is where Starboard (almost) nailed its thesis. They saw something the rest of the market was ignoring, the huge tailwinds of data consumption.

I say "almost" because they listed 5G ahead of AI, while AI is what has changed the narrative much more than 5G here.

Demand for data centers is ultimately driven by data consumption, which is expected to increase significantly for the foreseeable future.

This presentation was published at the end of October 2022, a month later, OpenAI would shock the world with the first release of ChatGPT

This is where Starboard (almost) nailed its thesis. They saw something the rest of the market was ignoring, the huge tailwinds of data consumption.

I say "almost" because they listed 5G ahead of AI, while AI is what has changed the narrative much more than 5G here.

Demand for data centers is ultimately driven by data consumption, which is expected to increase significantly for the foreseeable future.

This presentation was published at the end of October 2022, a month later, OpenAI would shock the world with the first release of ChatGPT

3) Lack of Urgency

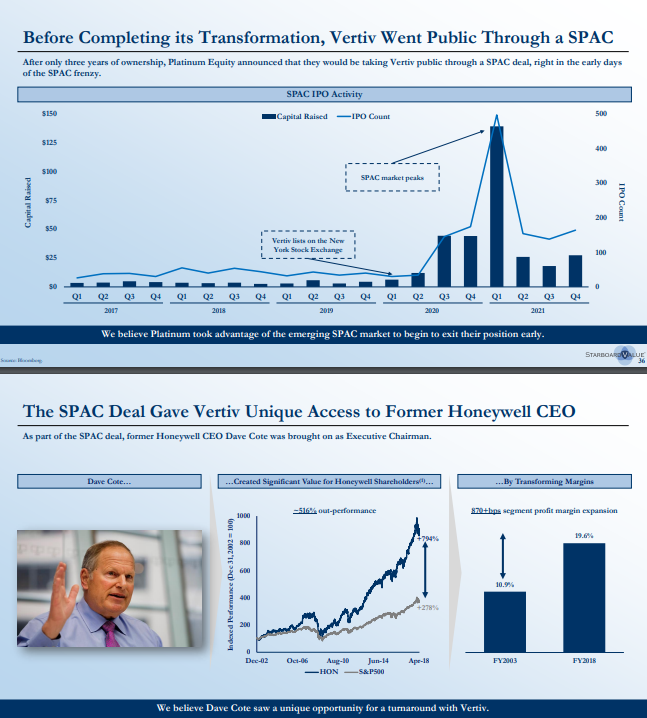

Vertiv was owned by Platinum Equity from 2016 to 2019, when it went public with a SPAC.

The SPAC Deal Gave Vertiv Unique Access to Former Honeywell CEO Starboard believes Dave Cote saw a unique opportunity for a turnaround with Vertiv but...

Vertiv was owned by Platinum Equity from 2016 to 2019, when it went public with a SPAC.

The SPAC Deal Gave Vertiv Unique Access to Former Honeywell CEO Starboard believes Dave Cote saw a unique opportunity for a turnaround with Vertiv but...

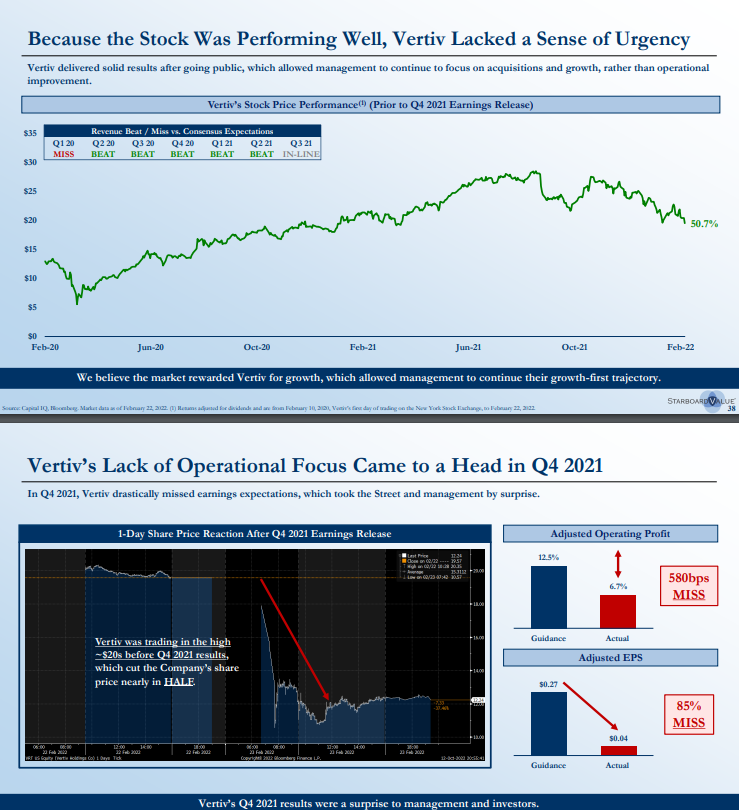

...because the Stock Was Performing Well (consistent beats), Vertiv Lacked a Sense of Urgency

Things were good, until they were not.

In Q4 2021, Vertiv drastically missed earnings expectations, which took the Street and management by surprise.

Vertiv was trading in the high ~$20s before Q4 2021 results, which cut the Company’s share price nearly in HALF.

Things were good, until they were not.

In Q4 2021, Vertiv drastically missed earnings expectations, which took the Street and management by surprise.

Vertiv was trading in the high ~$20s before Q4 2021 results, which cut the Company’s share price nearly in HALF.

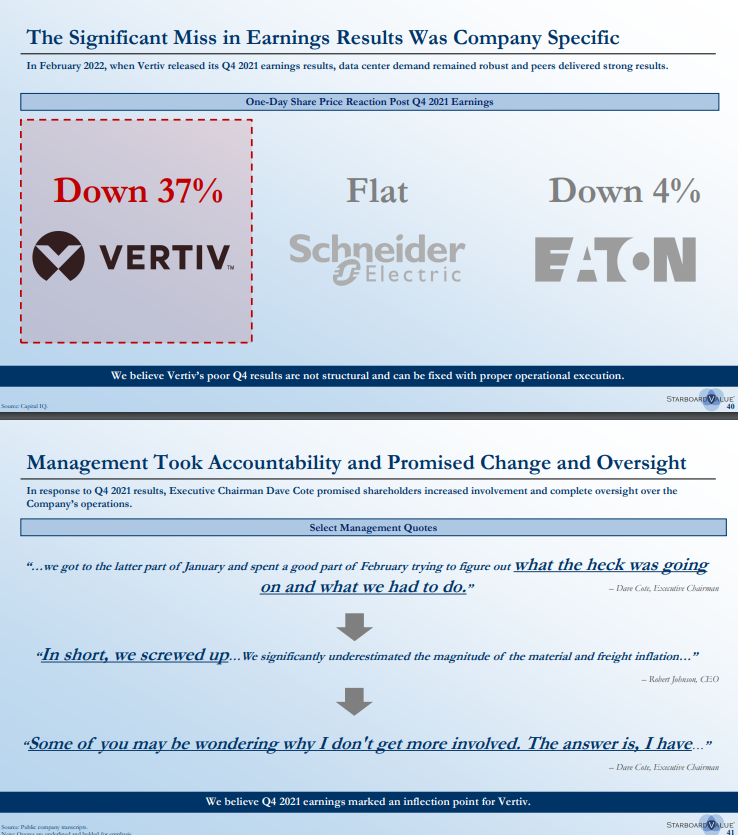

Worth noting how this miss was company specific, with its peers staying roughly flat

Luckily, In response to Q4 2021 results, Executive Chairman Dave Cote promised shareholders increased involvement and complete oversight over the Company’s operations.

“In short, we screwed up…We significantly underestimated the magnitude of the material and freight inflation…”

Luckily, In response to Q4 2021 results, Executive Chairman Dave Cote promised shareholders increased involvement and complete oversight over the Company’s operations.

“In short, we screwed up…We significantly underestimated the magnitude of the material and freight inflation…”

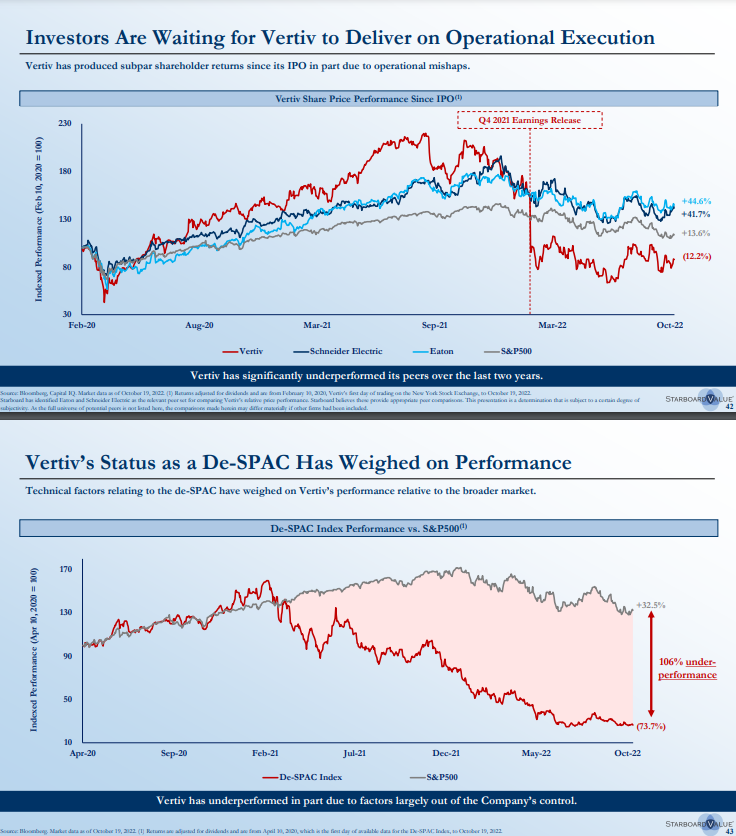

Up until October 2022, Investors were Waiting for Vertiv to Deliver on Operational Execution with the stock underperforming the S&P500 and its peers.

In addition, Starboard believed Vertiv’s Status as a De-SPAC Has Weighed on Performance

In addition, Starboard believed Vertiv’s Status as a De-SPAC Has Weighed on Performance

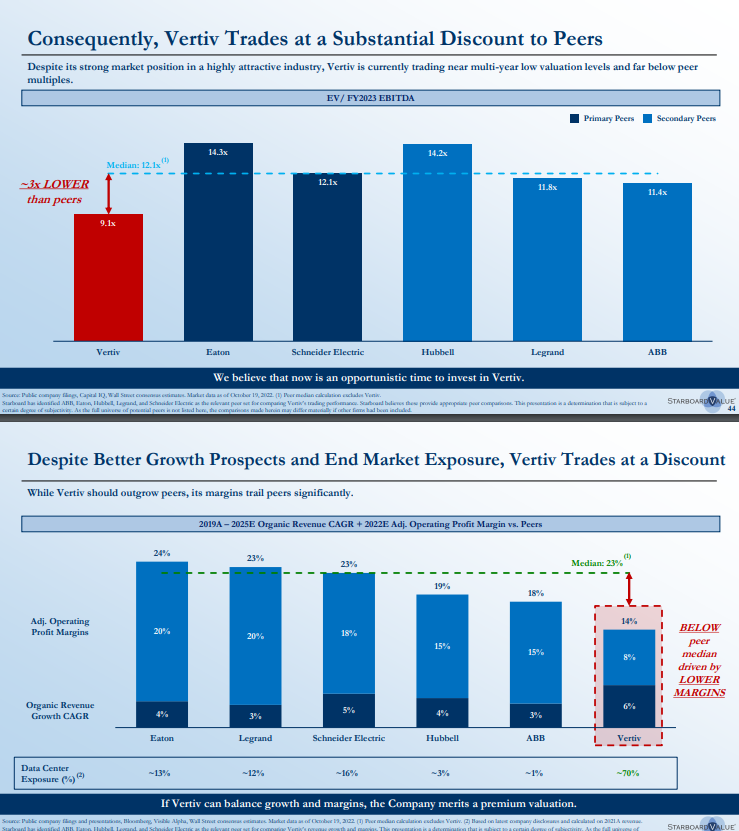

4) Valuation Discount

Despite its strong market position in a highly attractive industry, Vertiv was currently trading near multi-year low valuation levels and far below peer multiples.

Fundamentals, as always, were the answer: its margins trail peers significantly.

Despite its strong market position in a highly attractive industry, Vertiv was currently trading near multi-year low valuation levels and far below peer multiples.

Fundamentals, as always, were the answer: its margins trail peers significantly.

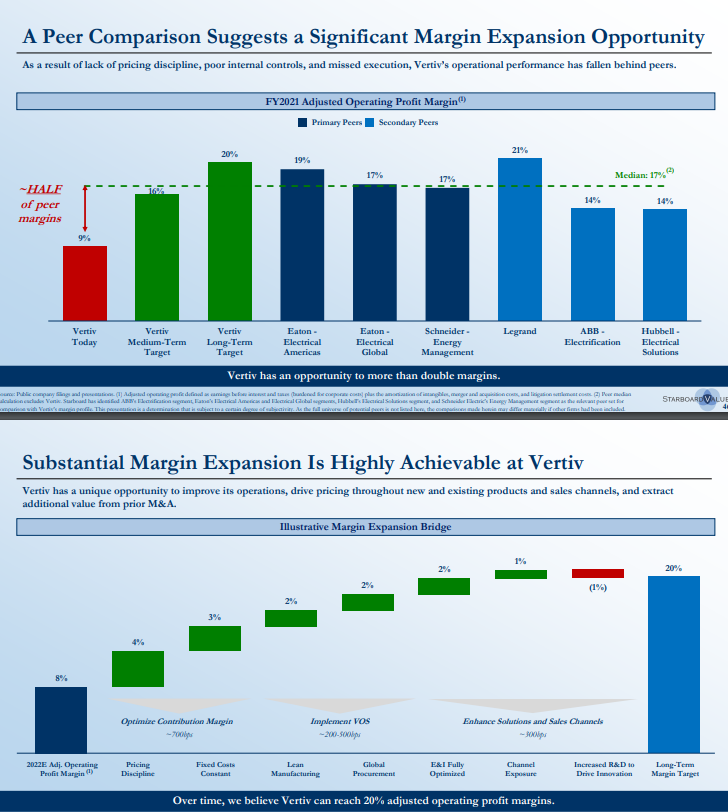

5) Margin Opportunity

Looking at its peers, Vertiv had an opportunity to more than double margins.

They had operating margin of 9%, and Starboard believed they could achieve 16% in medium term and 20% in long term.

Curious about what happened? In the LTM financials as of Dec-24, Vertiv has revenue of $7.5Bn with $1.2Bn of Operating Income for a 16% margin.

Absolutely nailed it.

Looking at its peers, Vertiv had an opportunity to more than double margins.

They had operating margin of 9%, and Starboard believed they could achieve 16% in medium term and 20% in long term.

Curious about what happened? In the LTM financials as of Dec-24, Vertiv has revenue of $7.5Bn with $1.2Bn of Operating Income for a 16% margin.

Absolutely nailed it.

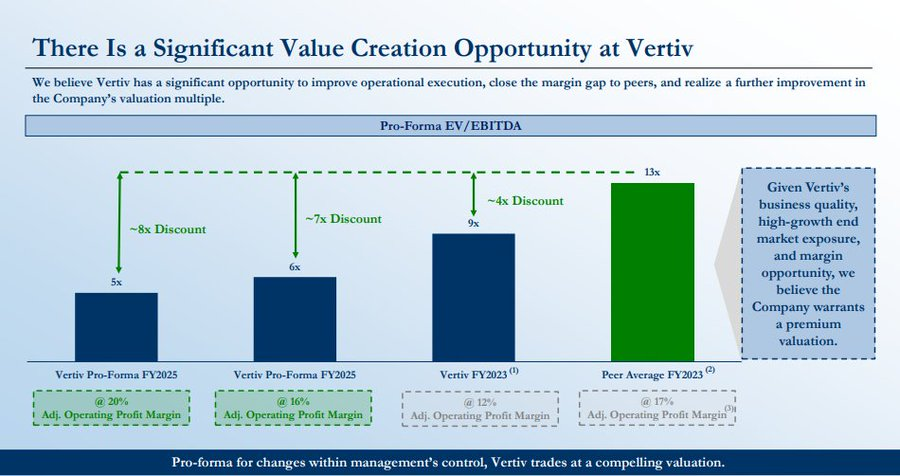

6) Multiple Opportunity

At the time of this pitch, Vertiv was trading at 9x NTM EBITDA. If the operating improvements were achieved, the stock would have implied a 6x 2025 EBITDA.

This compared to 13x for its peers. The discount (especially if you believed the margin story) was massive.

Curious about what happened? Vertiv now trades at 22x NTM EBITDA (13x turns of expansion!). For comparison, Eaton went from 14x to 16x (2x turns of expansion), and Schneider Electric went from 12x to 22x (10x turns of expansion).

Ladies and gentlemen, this is a masterclass in market timing. Take a bow.

At the time of this pitch, Vertiv was trading at 9x NTM EBITDA. If the operating improvements were achieved, the stock would have implied a 6x 2025 EBITDA.

This compared to 13x for its peers. The discount (especially if you believed the margin story) was massive.

Curious about what happened? Vertiv now trades at 22x NTM EBITDA (13x turns of expansion!). For comparison, Eaton went from 14x to 16x (2x turns of expansion), and Schneider Electric went from 12x to 22x (10x turns of expansion).

Ladies and gentlemen, this is a masterclass in market timing. Take a bow.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh