🧵 The Qur’an presents historical narratives not as conventional chronicles but often through typology: historical figures and events are structured as recurring patterns that illustrate moral, social, and political dynamics. (1/11)

Typology refers to the representation of a figure or event as a type: a model whose actions, decisions, and outcomes exemplify patterns that recur across contexts. The emphasis is on the pattern, not just the individual case. (2/11)

Western Scholars like Nicolai Sinai distinguish Qur’anic typology from historical re-enactment. He emphasizes the Qur’an’s patterns of fulfilment and surpassing previous figures or narratives, situating it in a broader typological framework (Workshop, SFB Episteme). (3/11)

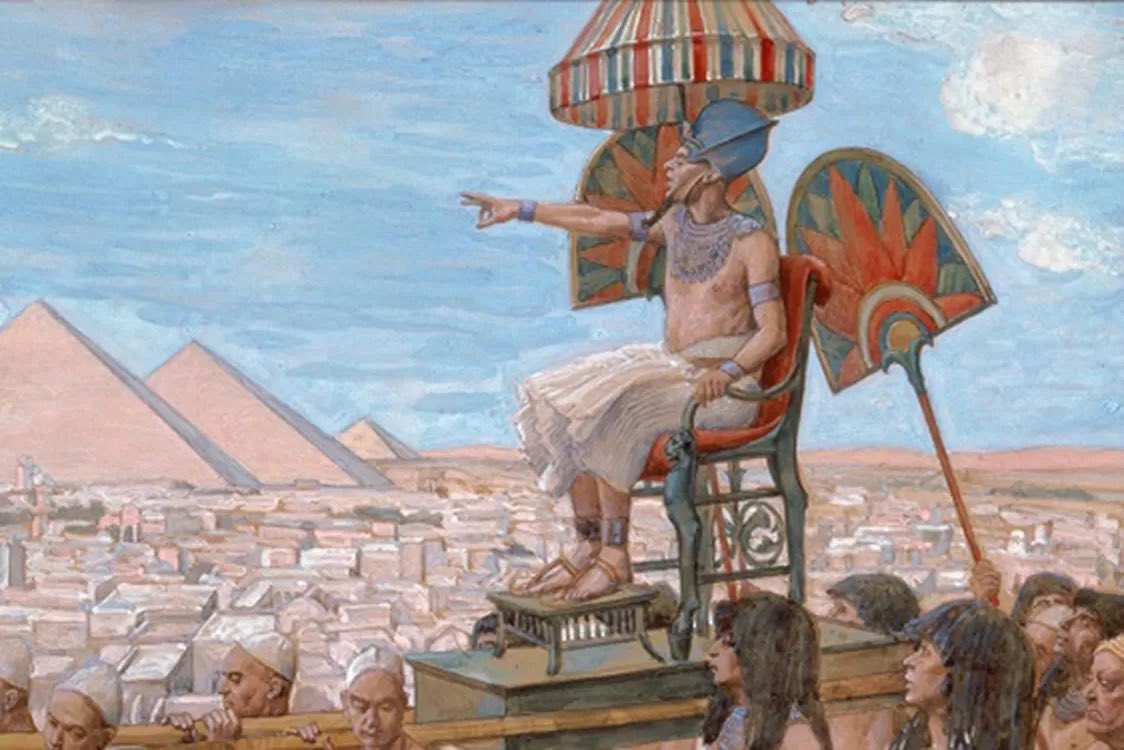

Consider Pharaoh:

“Pharaoh exalted himself in the land and divided its people into factions, oppressing a group among them…” (Q 28:4)

He functions both as a historical ruler and as a type of concentrated power, societal oppression, and rejection of guidance. (4/11)

“Pharaoh exalted himself in the land and divided its people into factions, oppressing a group among them…” (Q 28:4)

He functions both as a historical ruler and as a type of concentrated power, societal oppression, and rejection of guidance. (4/11)

Qarun (Q 28:76–82) represents wealth and hubris leading to ruin; the people of Lot (Q 7:80–84) demonstrate moral corruption and denial; ‘Ād (Q 7:65–72) exemplify prideful power ignoring guidance. These figures cluster around patterns of hubris and social failure. (5/11)

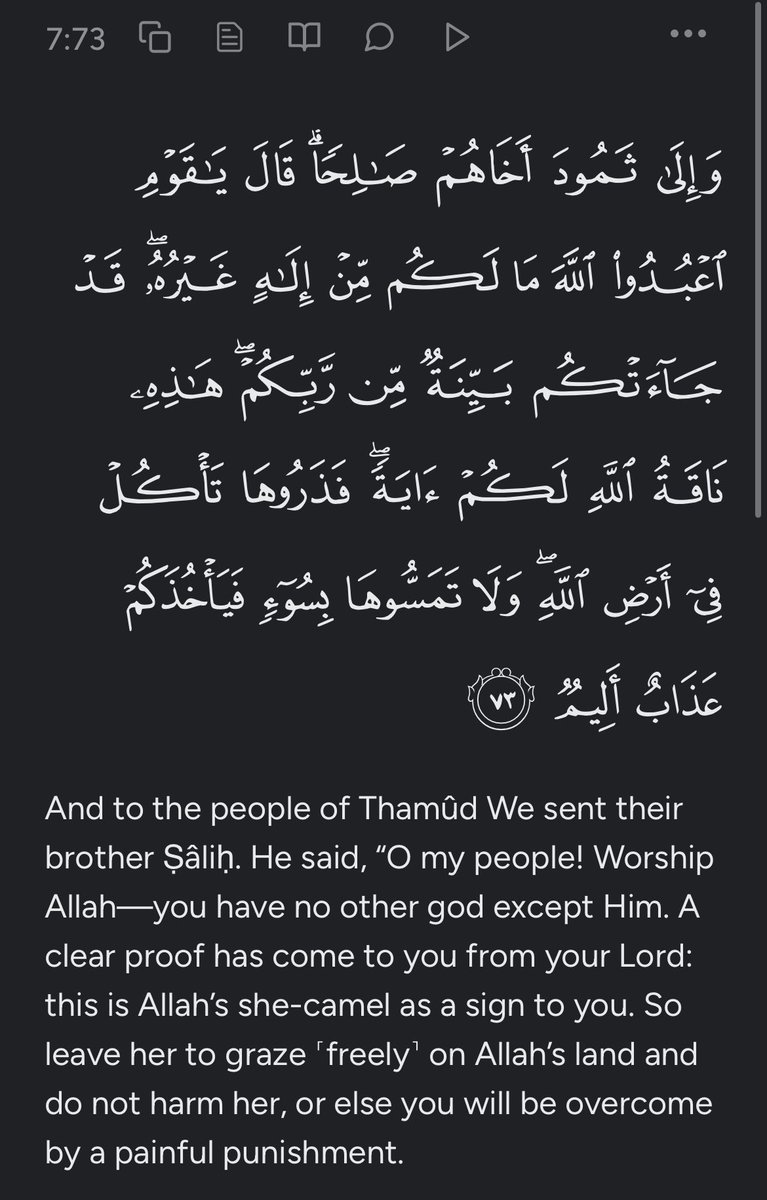

Other figures highlight recurrent dynamics: Haman (Q 28:38–42) embodies administrative complicity with authority; Queen of Sheba (Q 27:20–44) shows negotiation and consequences of decision-making; Thamud (Q 7:73–79) exemplifies societal hubris and denial. (6/11)

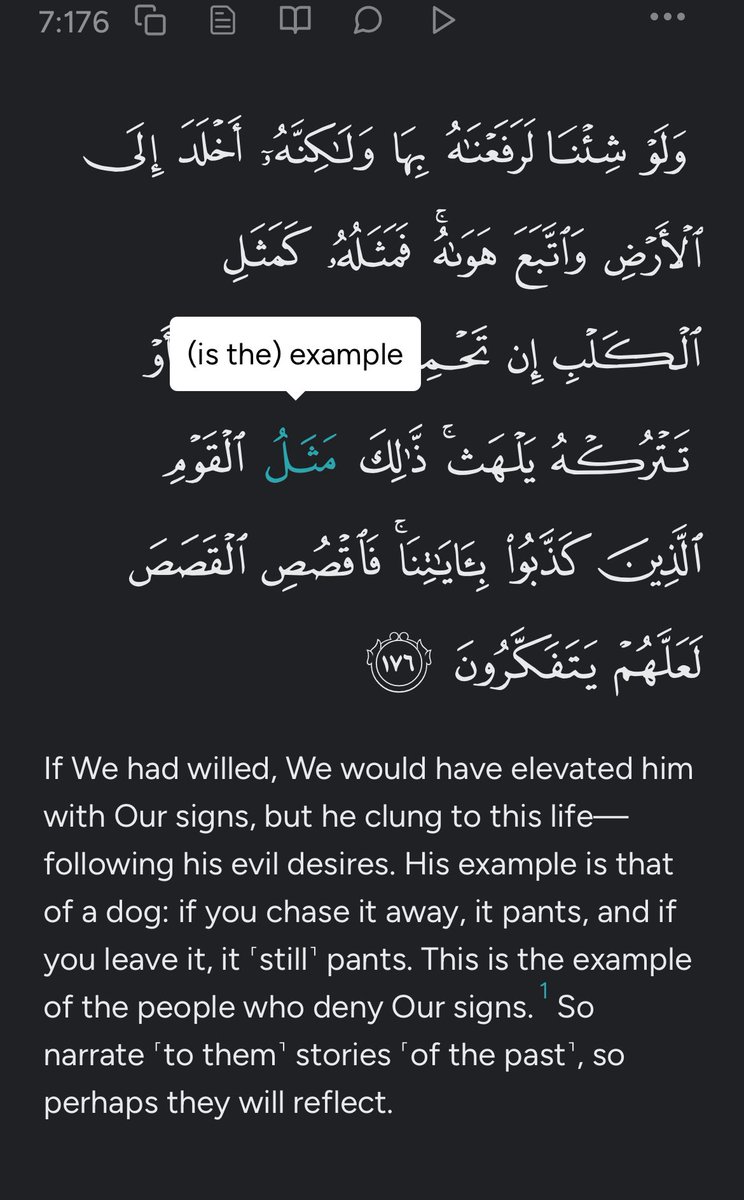

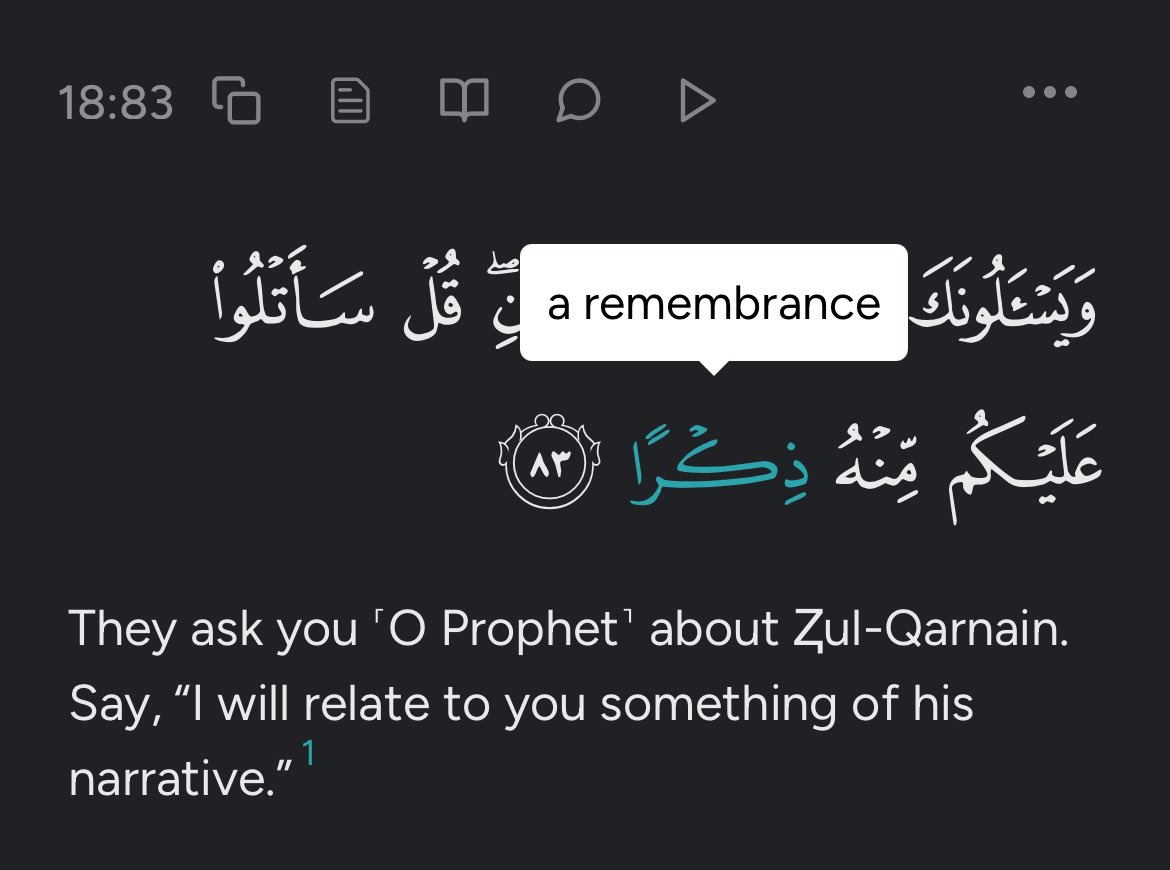

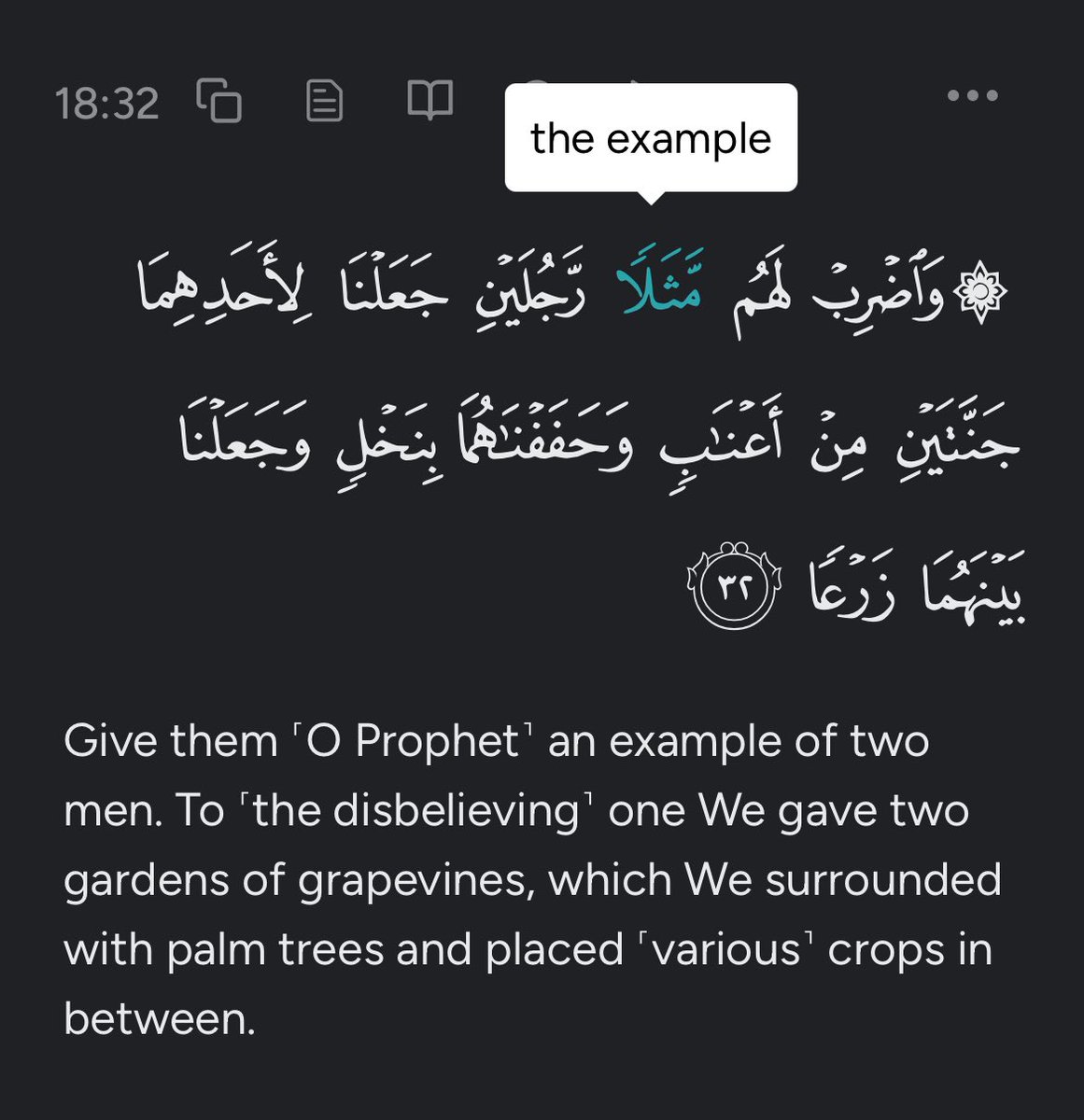

The Qur’an signals typology through linguistic cues, including kadhālika (thus), wa min qasasihim (from their stories), dhikr (reminder), mathal (parable), repeated reporting verbs, and ʿibrah (lesson). These cues suggest patterns, but their function is case by case. (7/11)

Using typology does not imply the Qur’an denies historicity. These figures are treated as real historical agents; typology emphasizes the analytical and interpretive lens through which their actions can be understood in terms of recurrent patterns. (8/11)

Despite variations in details names, locations, chronology, etc. Consistent moral and social patterns emerge: abuse of power, denial of guidance, accountability, and presence of exemplars showing obedience and discernment (9/11)

Methodologically, typology can be analyzed by tracking linguistic markers, narrative repetition, and structural parallels across Qur’anic stories. Patterns emerge probabilistically, offering insight into recurring human, social, and political dynamics. (10/11)

Reading Qur’anic narratives typologically transforms them into a systematic lens for understanding recurring patterns of human behavior, governance, and social response. Each story functions as a case study, showing dynamics that persist across time. (11/11)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh