How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

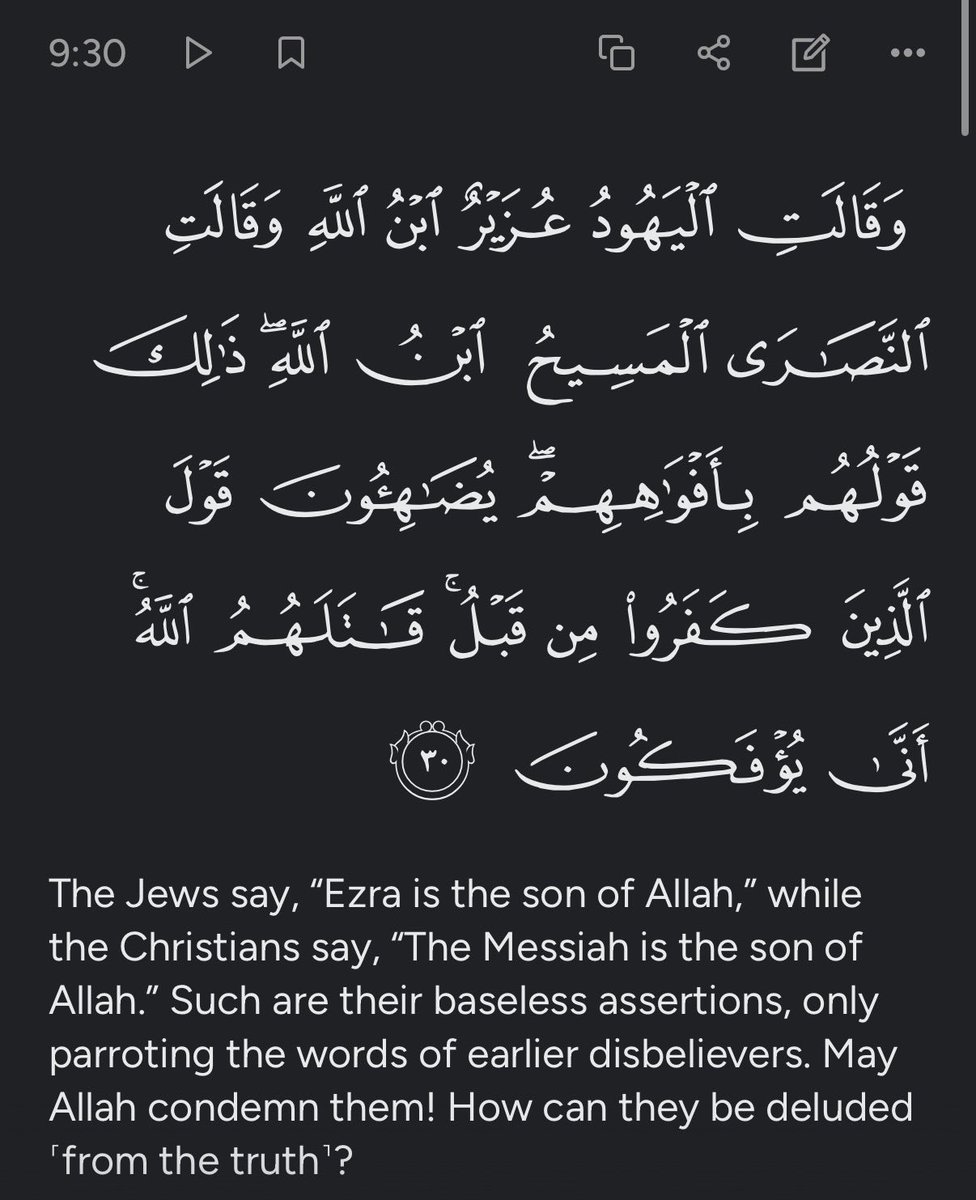

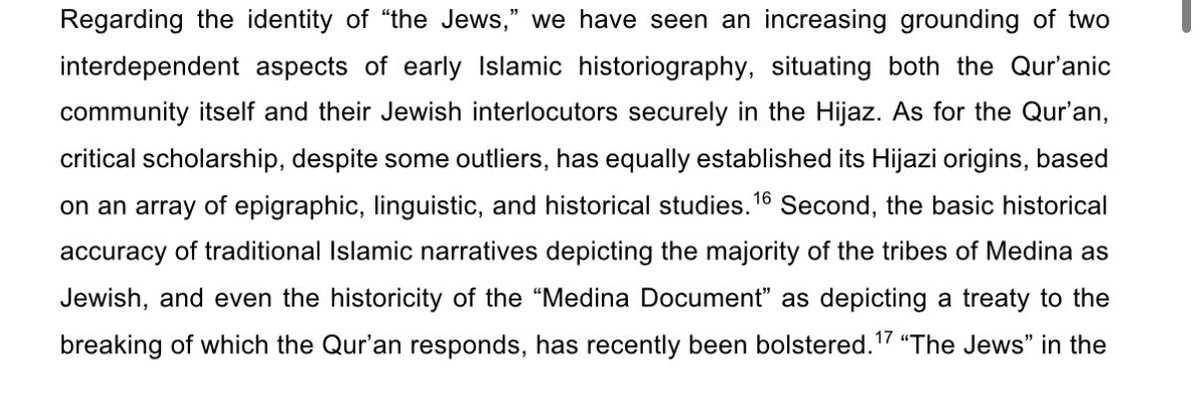

The Qur’an primarily addresses Jews from Medina, Khaybar, and the Hijaz. Evidence about them is sparse (just inscriptions, archaeology, and early Islamic literature) but the Qur’an itself provides crucial insight into their beliefs and practices. (2/23)

The Qur’an primarily addresses Jews from Medina, Khaybar, and the Hijaz. Evidence about them is sparse (just inscriptions, archaeology, and early Islamic literature) but the Qur’an itself provides crucial insight into their beliefs and practices. (2/23)

Whether one views Western academia as colonialist or not, the experience of being a Muslim in the academy still carries stark dualities. Borrowing a phrase from Frantz Fanon, it is a manichaean existence. (2/19)

Whether one views Western academia as colonialist or not, the experience of being a Muslim in the academy still carries stark dualities. Borrowing a phrase from Frantz Fanon, it is a manichaean existence. (2/19)

The standard narrative says Prophet Muhammad appears “out of the blue” in a pagan Arabia unfamiliar with prophecy. This picture does not survive close scrutiny of the sources. (2/

The standard narrative says Prophet Muhammad appears “out of the blue” in a pagan Arabia unfamiliar with prophecy. This picture does not survive close scrutiny of the sources. (2/

Traditionalists assume literalism, yet the text shows chronological compression, recast scenes across surahs, and clear Late Antique intertextuality. These are not small glitches. They form a pattern that challenges a simple literal frame. (2/9)

Traditionalists assume literalism, yet the text shows chronological compression, recast scenes across surahs, and clear Late Antique intertextuality. These are not small glitches. They form a pattern that challenges a simple literal frame. (2/9)

Van Putten and questions on intertextuality. (2/?)

Van Putten and questions on intertextuality. (2/?)https://x.com/dmontetheno1/status/1958413009564352943?s=46

Scholars like Fred Donner argue early Islam was “The Believers’ Movement”: an ecumenical fellowship of Jews, Christians, and Muslims united by monotheism and righteous conduct. Universal from the start, not tied to ethnicity or genealogy. (2/15)

Scholars like Fred Donner argue early Islam was “The Believers’ Movement”: an ecumenical fellowship of Jews, Christians, and Muslims united by monotheism and righteous conduct. Universal from the start, not tied to ethnicity or genealogy. (2/15)

Verses such as Q 23:115 ask: “Did you think We created you in vain?” Similarly, Q 3:190-191 affirms that creation is neither false nor meaningless. Decharneux highlights how these passages underscore a rejection of purposelessness. (2/9)

Verses such as Q 23:115 ask: “Did you think We created you in vain?” Similarly, Q 3:190-191 affirms that creation is neither false nor meaningless. Decharneux highlights how these passages underscore a rejection of purposelessness. (2/9)

Typology refers to the representation of a figure or event as a type: a model whose actions, decisions, and outcomes exemplify patterns that recur across contexts. The emphasis is on the pattern, not just the individual case. (2/11)

Typology refers to the representation of a figure or event as a type: a model whose actions, decisions, and outcomes exemplify patterns that recur across contexts. The emphasis is on the pattern, not just the individual case. (2/11)

The Qur’an does not merely say nāqa (“camel”). It says nāqat Allāh “God’s camel” (7:73, 11:64, 26:155, 91:13). This divine possession is unusual. The only consistent parallel is Bayt Allāh, the Kaʿbah. (2/9)

The Qur’an does not merely say nāqa (“camel”). It says nāqat Allāh “God’s camel” (7:73, 11:64, 26:155, 91:13). This divine possession is unusual. The only consistent parallel is Bayt Allāh, the Kaʿbah. (2/9)

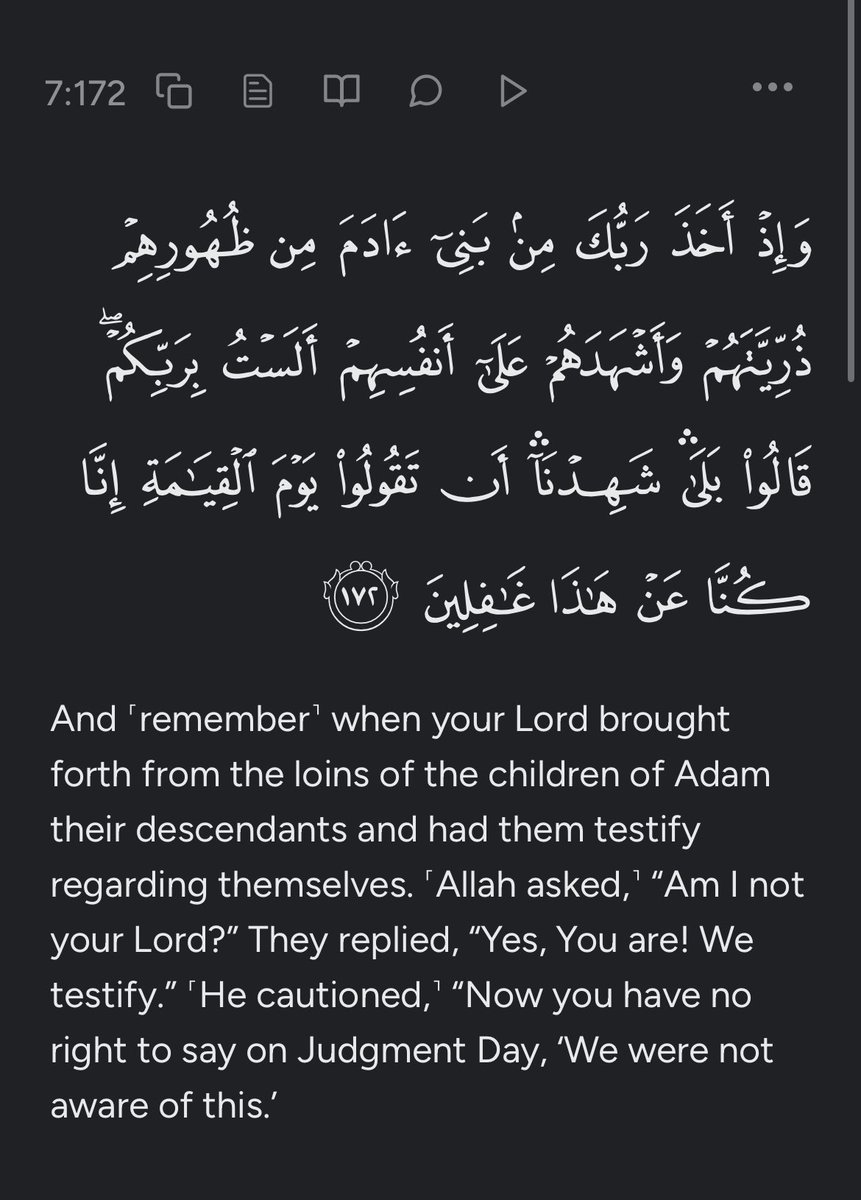

Using Q 7:172, we see the verse depicts a pre-temporal covenant with humanity. (2/10)

Using Q 7:172, we see the verse depicts a pre-temporal covenant with humanity. (2/10)

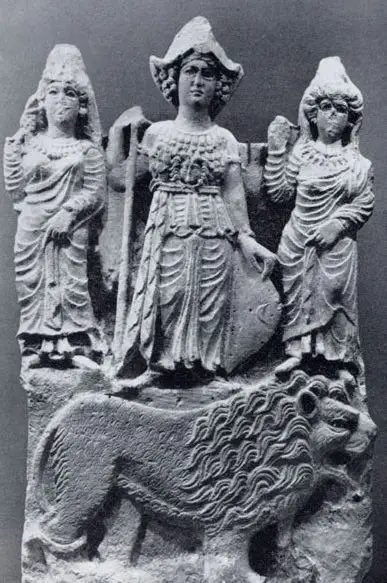

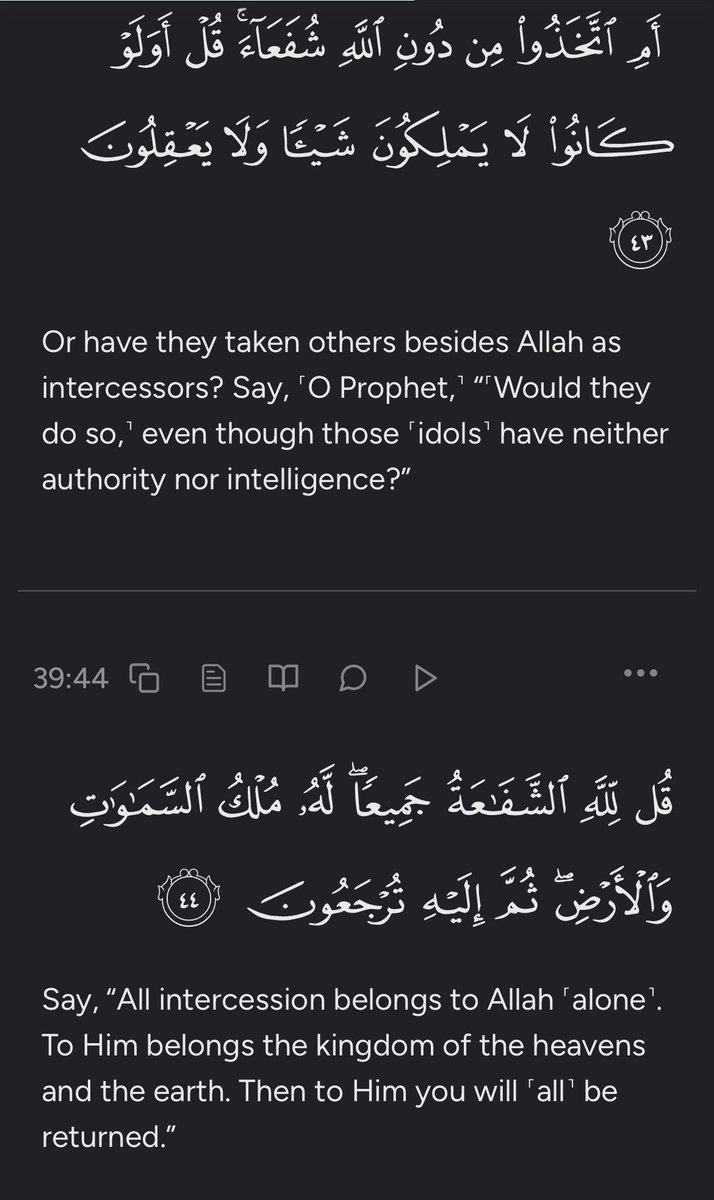

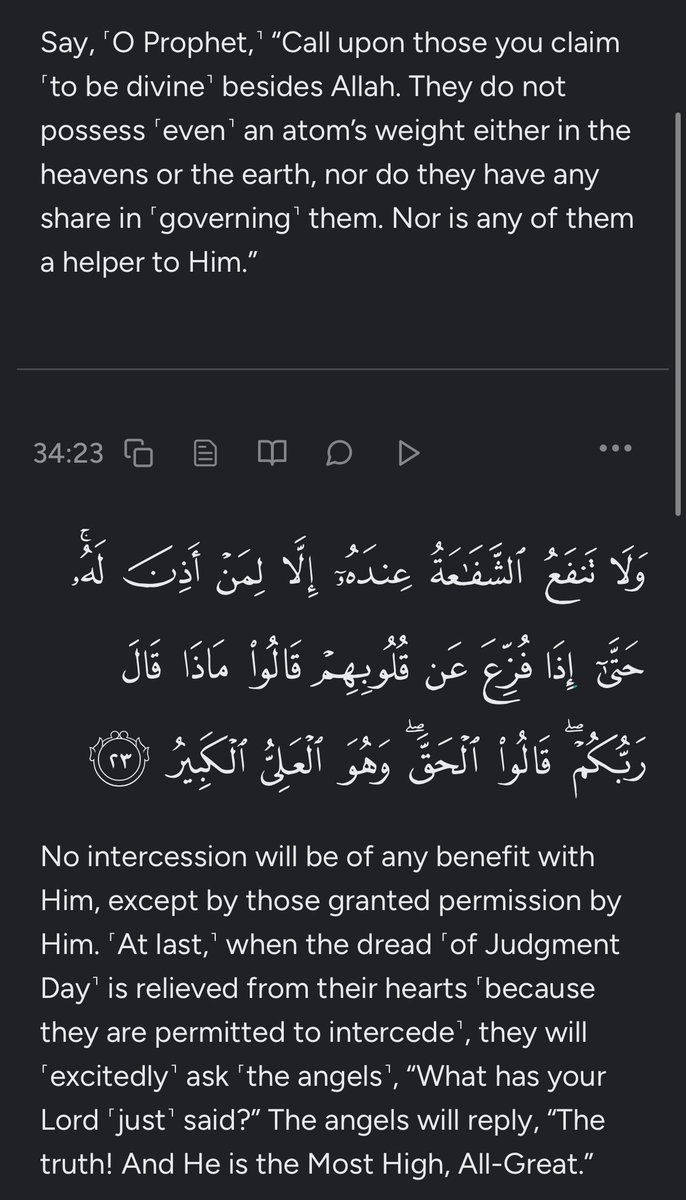

The Qur’an doesn’t portray the mushrikūn as your standard polytheist. They acknowledged Allah but prayed to others as intercessors.

The Qur’an doesn’t portray the mushrikūn as your standard polytheist. They acknowledged Allah but prayed to others as intercessors.

Tarhīb is the rhetoric of deterrence. Passages like Q.14:47–51 paint Hell with sensory detail: chains, fire, garments of pitch. The goal isn’t abstract doctrine, it’s to shock and move the listener at a gut level. (2/6)

Tarhīb is the rhetoric of deterrence. Passages like Q.14:47–51 paint Hell with sensory detail: chains, fire, garments of pitch. The goal isn’t abstract doctrine, it’s to shock and move the listener at a gut level. (2/6)

https://twitter.com/gabrielsaidr/status/1960682418651689229

Before we get into the questions I want to clarify this is not an attack on Professor Reynolds. I am simply setting expectations that need to be addressed to fully support the claims he is making. The book is not out yet and I will not make full judgments until then. (2/12)

Before we get into the questions I want to clarify this is not an attack on Professor Reynolds. I am simply setting expectations that need to be addressed to fully support the claims he is making. The book is not out yet and I will not make full judgments until then. (2/12)

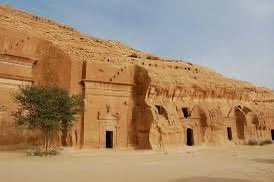

The Quran emphasizes that ruins form a distinct category of ayat. They are meant to be examined, not simply noted, guiding readers toward understanding the patterns of social success, failure, and moral consequence. (2/10)

The Quran emphasizes that ruins form a distinct category of ayat. They are meant to be examined, not simply noted, guiding readers toward understanding the patterns of social success, failure, and moral consequence. (2/10)

https://twitter.com/chonkshonk1/status/1924566879172989211The triliteral root w-f-y simply means “to take in full” or “to complete.” In the form tawaffā, it can refer to death but it just as often refers to non-lethal withdrawal, including in sleep (Q 6:60; Q 39:42). Context determines meaning.