1/ Every political order must answer the oldest question of all: how to restrain the conflict between the few and the many.

Patrick Deneen has become one of the most prominent mainstream critics of the liberal order. His widely discussed book “Why Liberalism Failed” contrasted the promises of the tradition with the evident decay of our present.

His more recent “Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future” advances the argument by proposing remedies, with particular emphasis on the recovery of the mixed constitution, an ancient device for reconciling classes and preserving civic stability.

Patrick Deneen has become one of the most prominent mainstream critics of the liberal order. His widely discussed book “Why Liberalism Failed” contrasted the promises of the tradition with the evident decay of our present.

His more recent “Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future” advances the argument by proposing remedies, with particular emphasis on the recovery of the mixed constitution, an ancient device for reconciling classes and preserving civic stability.

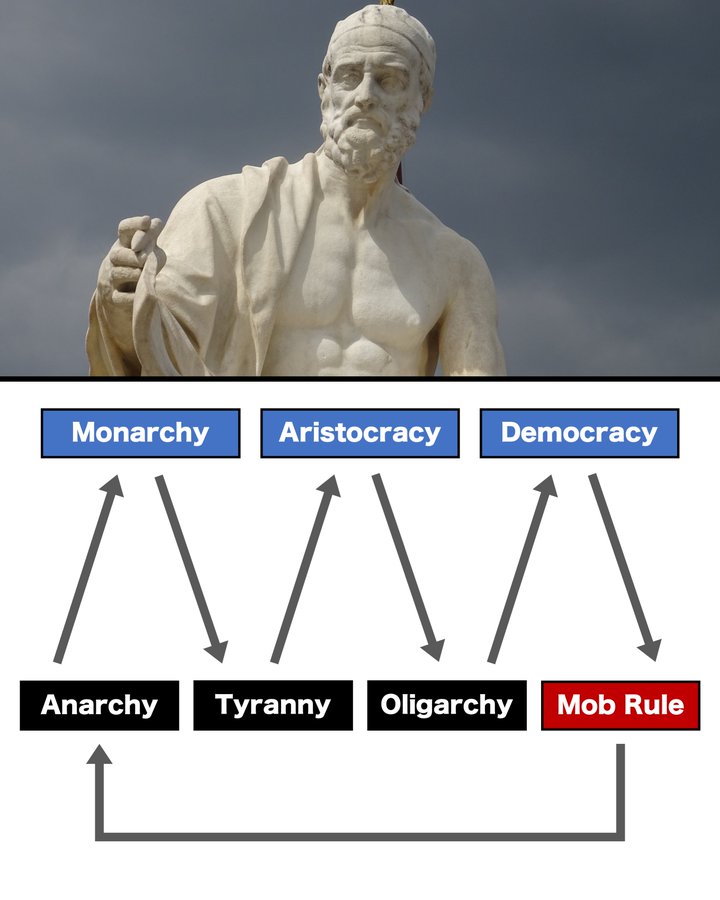

2/ Deneen situates his argument within a much older problem, one that the Greeks themselves faced. Their cities were repeatedly consumed by class struggle, oligarchs contending with democrats, at times resorting to the annihilation of rivals. From such experience came the first attempts to understand politics as the art of restraining conflict by cultivating the virtues of each class while suppressing their vices.

The wealthy enjoyed refinement and leisure, yet often succumbed to arrogance and selfishness. The poor, hardened by necessity, lived with frugality and endurance, yet remained vulnerable to envy and demagoguery. Aristotle, Polybius, and others proposed the mixed constitution as the answer: a structure balancing these forces, or a broad middle element capable of stabilizing extremes.

The wealthy enjoyed refinement and leisure, yet often succumbed to arrogance and selfishness. The poor, hardened by necessity, lived with frugality and endurance, yet remained vulnerable to envy and demagoguery. Aristotle, Polybius, and others proposed the mixed constitution as the answer: a structure balancing these forces, or a broad middle element capable of stabilizing extremes.

3/ Modern liberalism emerged centuries later with the rejection of feudal privileges. Yet it did not empower the many. Instead, it elevated a new elite of the “industrious and rational,” entrusted with directing society while shielding their activity from interference by the masses. Early liberals hoped that rising prosperity would reconcile the majority to this minority rule. When material progress came, later liberals sought to extend it into the moral sphere, dissolving local attachments in favor of national or even universal solidarity.

John Stuart Mill, writing in the nineteenth century, gave this tendency its most complete expression. He regarded inherited custom as a form of despotism, advocated plural voting to weight politics toward the educated, and proposed the “harm principle” as the measure of law. He even justified coercion abroad, insisting that “progress” must be imposed upon peoples incapable of valuing it without compulsion.

John Stuart Mill, writing in the nineteenth century, gave this tendency its most complete expression. He regarded inherited custom as a form of despotism, advocated plural voting to weight politics toward the educated, and proposed the “harm principle” as the measure of law. He even justified coercion abroad, insisting that “progress” must be imposed upon peoples incapable of valuing it without compulsion.

4/ Marxism offered another progressive doctrine, one that proclaimed the many as the motor of change. Yet even here, faith in the working class faltered. Marx himself admitted that elites would have to initiate measures in the workers’ name. Lenin created a vanguard. Later Marxists, such as the Frankfurt School, abandoned the proletariat altogether. What united liberal and Marxist traditions was not their attitude to progress, but their dismissal of the classical concern with balance between classes. The ancient ideal of a mixed constitution was treated as antiquarian.

Deneen argues that today’s liberal elite is of a new type, unprecedented in form and outlook. Its authority does not rest upon land, arms, or hereditary station, but upon fungible skills certified by credentials. Its ideology is hostile to hierarchy, even as its members reproduce privilege for their children. It cloaks its dominance in the language of meritocracy, wielding Mill’s harm principle against remnants of inherited order. Its command rests not only on the state but on corporations, media, and universities. It is what James Burnham described in “The Managerial Revolution”: a class of specialists, managers, and technicians whose power derives from skills in finance, data manipulation, and bureaucratic administration.

Deneen argues that today’s liberal elite is of a new type, unprecedented in form and outlook. Its authority does not rest upon land, arms, or hereditary station, but upon fungible skills certified by credentials. Its ideology is hostile to hierarchy, even as its members reproduce privilege for their children. It cloaks its dominance in the language of meritocracy, wielding Mill’s harm principle against remnants of inherited order. Its command rests not only on the state but on corporations, media, and universities. It is what James Burnham described in “The Managerial Revolution”: a class of specialists, managers, and technicians whose power derives from skills in finance, data manipulation, and bureaucratic administration.

5/ This elite differs from its predecessors in another respect. Aristocracies once recognized that inherited status entailed obligations to the community. Today’s meritocrats believe they earned their place entirely through talent and effort, and so they feel no duty toward those below them. Their loyalty extends only to their children, whom they advance through marriage, private schooling, and admissions gamesmanship. Their education system serves as both recruitment mechanism and instrument of dissolution, stripping away tradition while training recruits to navigate a world without guardrails. Dissent is permitted only when directed against the past, never against the regime itself.

The hypocrisy is plain in the treatment of small businesses during the Covid lockdowns. Multinational corporations remained open and thrived, while family shops and local establishments were ordered shut, many of them permanently. What was proclaimed as a public safeguard in practice meant the ruin of the weak and the enrichment of the strong. Such moments expose the inversion at the core of liberal equality: not a leveling of conditions, but a means of disciplining the many. The harm principle, already invoked earlier, has been twisted from a safeguard of liberty into a charter for grievance, wielded by favored groups to enforce conformity.

The hypocrisy is plain in the treatment of small businesses during the Covid lockdowns. Multinational corporations remained open and thrived, while family shops and local establishments were ordered shut, many of them permanently. What was proclaimed as a public safeguard in practice meant the ruin of the weak and the enrichment of the strong. Such moments expose the inversion at the core of liberal equality: not a leveling of conditions, but a means of disciplining the many. The harm principle, already invoked earlier, has been twisted from a safeguard of liberty into a charter for grievance, wielded by favored groups to enforce conformity.

6/ Detached from place, today’s elites cannot comprehend the ordinary man’s loyalty to his people and his soil. They urge displaced workers to move to Silicon Valley, farmers dispossessed of ancestral fields to “learn to code.” Their obtuseness recalls Marie Antoinette’s “let them eat cake,” though they lack even her dim awareness of what befell her. Their hostility to rootedness aligns them with uprooted migrants, whose labor they exploit and whose presence they use to discipline native dissent. For this ruling class, “elite” itself has become a term of contempt. Aristocracies once called themselves the best men. Our rulers are despised even as they claim legitimacy in the name of expertise.

The defense of expertise is central to the modern order. Plato had floated philosopher-kings as a thought experiment, but modernity made the authority of experts its cornerstone. Administration was professionalized, governance rationalized, and the cult of science enthroned. Yet science never dictates policy. Facts require judgment, and judgments belong to men with interests. Covid-era injunctions to “trust the science” revealed the dogma at work. Aristotle long ago argued that common sense often judges better than expertise: the inhabitant of a house knows more of its strengths and flaws than the architect who designed it. Today’s populists echo this truth when they resist administrators who redesign their lives from afar.

The defense of expertise is central to the modern order. Plato had floated philosopher-kings as a thought experiment, but modernity made the authority of experts its cornerstone. Administration was professionalized, governance rationalized, and the cult of science enthroned. Yet science never dictates policy. Facts require judgment, and judgments belong to men with interests. Covid-era injunctions to “trust the science” revealed the dogma at work. Aristotle long ago argued that common sense often judges better than expertise: the inhabitant of a house knows more of its strengths and flaws than the architect who designed it. Today’s populists echo this truth when they resist administrators who redesign their lives from afar.

7/ Specialization, the foundation of modern productivity, has narrowed minds as well as labor. The expert knows more about less, mistaking technical proficiency for wisdom. Our managerial class excels at actuarial calculation and risk modeling, but this is not human merit in any higher sense. It has produced no Goethes or Shakespeares, only clever functionaries. The expansion of organization has been quantitative, not qualitative. By contrast, the common sense of the people, distilled in custom and proverbs, is broader and wiser than the fragmented knowledge of specialists. It is also more democratic, rooted in lived experience rather than technocratic fiat.

The liberal elite insists that talent is private property, that rewards are personal entitlements, and that obligations to the wider community are voluntary. This has created an elite without stewardship, one that proclaims concern for the poor in abstraction while evading all particular responsibility. Deneen calls for a renewal of elite formation, one grounded in service to the common good, tasked with preserving family, community, work, and cultural order. The present rulers cannot be persuaded into this role; they must be replaced.

The liberal elite insists that talent is private property, that rewards are personal entitlements, and that obligations to the wider community are voluntary. This has created an elite without stewardship, one that proclaims concern for the poor in abstraction while evading all particular responsibility. Deneen calls for a renewal of elite formation, one grounded in service to the common good, tasked with preserving family, community, work, and cultural order. The present rulers cannot be persuaded into this role; they must be replaced.

8/ The rise of populism signals this necessity. It is not the work of established conservatism but of ordinary men alienated from a way of life destroyed by elites and their clients. Its most visible figure, Donald Trump, has voiced grievances more than he has articulated a program. He has failed to build institutions or nurture a capable leadership, but he remains the emblem of popular defiance. The conditions that produced him are undeniable. Once, an American of modest means could sustain a family, own a home, and participate in civic life. That world was dissolved not by poverty but by structural choices that favored the few at the expense of the many.

Deneen proposes a political economy that restores balance: wages sufficient for families, constraints on corporate power, limits on destabilizing change, and policies that favor stability over wealth concentration. But he also insists that the people must reform themselves, overcoming divorce, addiction, consumer debt, and civic withdrawal. A new regime must elevate the many as well as restrain the few.

Deneen proposes a political economy that restores balance: wages sufficient for families, constraints on corporate power, limits on destabilizing change, and policies that favor stability over wealth concentration. But he also insists that the people must reform themselves, overcoming divorce, addiction, consumer debt, and civic withdrawal. A new regime must elevate the many as well as restrain the few.

9/ Immigration remains decisive. Liberal elites embrace it not only as cheap labor but as a weapon against native resistance. It secures their wealth while dissolving the cohesion of those who might oppose them.

Here Deneen falters. He hesitates to confront the central fact of our time: demographic change. Instead he imagines solidarity across group lines, as if economic interests could dissolve civilizational difference. This is illusion, and it invalidates his project. A postliberal order that refuses to recognize the people as a historical and ethnocultural body is no order at all.

The truth is plain. The White native stock must fight its own battles. Demographic transformation is not a policy detail but a reconstitution of the nation itself. It ensures conflict will not vanish into harmony but will harden along ethnocultural and civilizational lines.

Liberalism will not disappear of its own accord. It must be broken and driven down from total regime to faction, from command to contest. Only then will politics be restored as struggle: the few held accountable by the many, and elites compelled to justify their place as stewards rather than predators.

Here Deneen falters. He hesitates to confront the central fact of our time: demographic change. Instead he imagines solidarity across group lines, as if economic interests could dissolve civilizational difference. This is illusion, and it invalidates his project. A postliberal order that refuses to recognize the people as a historical and ethnocultural body is no order at all.

The truth is plain. The White native stock must fight its own battles. Demographic transformation is not a policy detail but a reconstitution of the nation itself. It ensures conflict will not vanish into harmony but will harden along ethnocultural and civilizational lines.

Liberalism will not disappear of its own accord. It must be broken and driven down from total regime to faction, from command to contest. Only then will politics be restored as struggle: the few held accountable by the many, and elites compelled to justify their place as stewards rather than predators.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh