The clash no one saw coming: two blockbuster drugs working against each other.

Statins lower cholesterol—but new research shows they also slash GLP-1, the same hormone Ozempic is designed to restore.

It’s a metabolic paradox with life-changing consequences for millions.

And here’s the kicker: the damage might be reversible with a dirt-cheap supplement… yet no one is talking about it.

Why? The answer may have little to do with science—and everything to do with money.

🧵 THREAD

Statins lower cholesterol—but new research shows they also slash GLP-1, the same hormone Ozempic is designed to restore.

It’s a metabolic paradox with life-changing consequences for millions.

And here’s the kicker: the damage might be reversible with a dirt-cheap supplement… yet no one is talking about it.

Why? The answer may have little to do with science—and everything to do with money.

🧵 THREAD

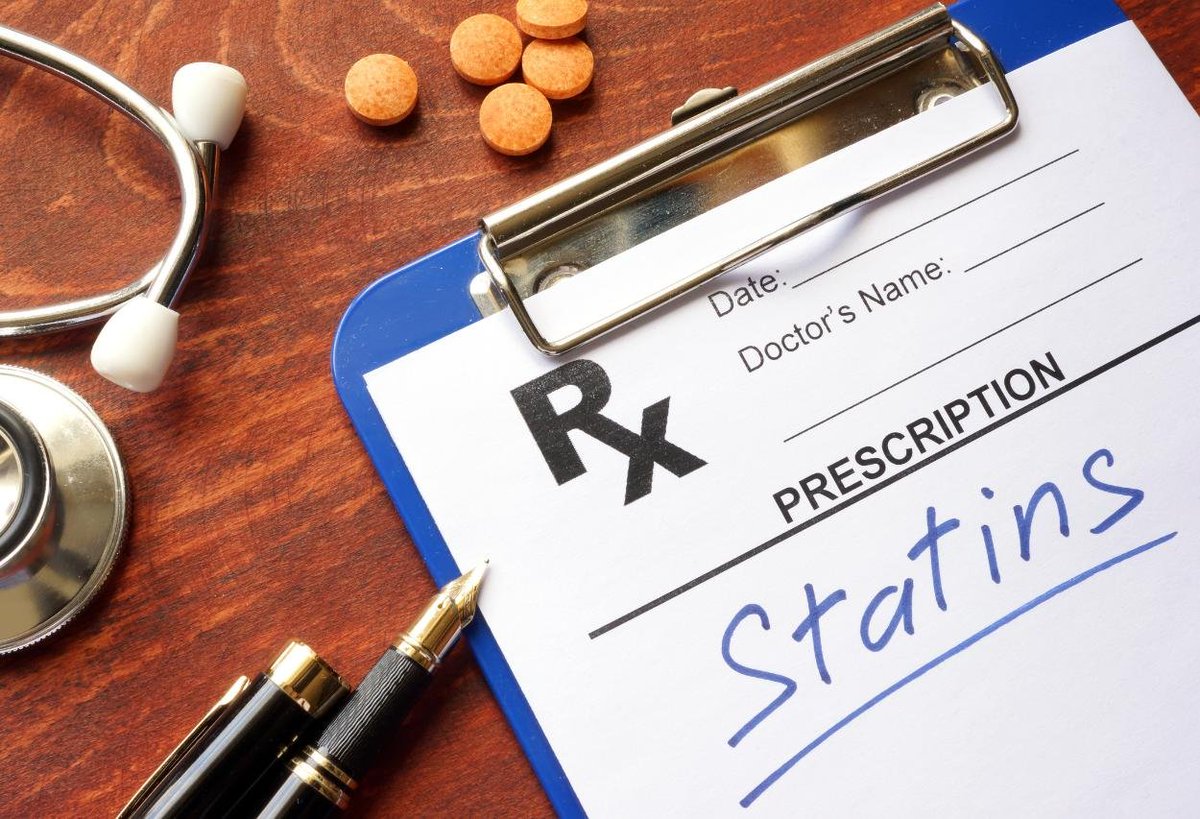

For decades, statins have been prescribed to tens of millions of Americans to lower cholesterol and ward off heart disease. Today, about one in three adults takes them.

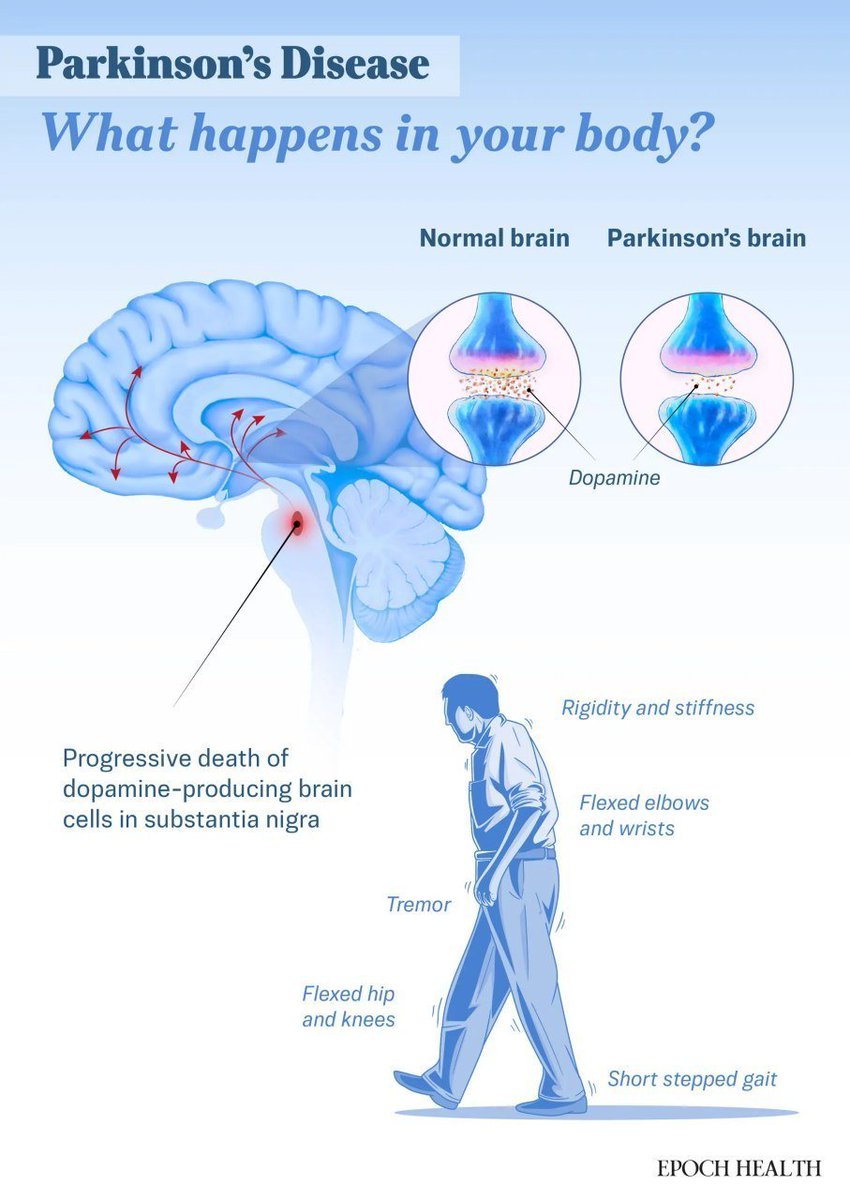

However, a 2024 study published in Cell Metabolism suggests these drugs may quietly disrupt another part of the body’s metabolism. Patients on atorvastatin, one of the most common statins, saw their levels of GLP-1—the hormone mimicked by Ozempic and other weight-loss drugs—drop by nearly half.

The finding suggests that while statins lower cholesterol, they may also nudge metabolism in the opposite direction, raising blood sugar and weight, both key drivers of heart disease. Early evidence hints the effect might be reversible with a simple supplement, yet the discovery has barely touched medical training or patient care.

However, a 2024 study published in Cell Metabolism suggests these drugs may quietly disrupt another part of the body’s metabolism. Patients on atorvastatin, one of the most common statins, saw their levels of GLP-1—the hormone mimicked by Ozempic and other weight-loss drugs—drop by nearly half.

The finding suggests that while statins lower cholesterol, they may also nudge metabolism in the opposite direction, raising blood sugar and weight, both key drivers of heart disease. Early evidence hints the effect might be reversible with a simple supplement, yet the discovery has barely touched medical training or patient care.

The Study

In the randomized controlled trial, 30 people starting atorvastatin were tracked for four months alongside 10 controls. Cholesterol fell as expected, but blood sugar edged up, insulin resistance worsened, and GLP-1 levels plunged by nearly half.

Researchers traced the mechanism to the gut. Statins reduced Clostridium bacteria, which make a bile acid called UDCA. That bile acid normally helps the body produce GLP-1. With fewer microbes, UDCA fell—and so did GLP-1. In other words, statins disrupted a microbial pathway that helps the body regulate blood sugar.

“With sets of experiments the researchers used, they make a very convincing case for that connection,” Dr. Adrian Soto-Mota, a physician-scientist who studies metabolic disease, told The Epoch Times in an email.

In the randomized controlled trial, 30 people starting atorvastatin were tracked for four months alongside 10 controls. Cholesterol fell as expected, but blood sugar edged up, insulin resistance worsened, and GLP-1 levels plunged by nearly half.

Researchers traced the mechanism to the gut. Statins reduced Clostridium bacteria, which make a bile acid called UDCA. That bile acid normally helps the body produce GLP-1. With fewer microbes, UDCA fell—and so did GLP-1. In other words, statins disrupted a microbial pathway that helps the body regulate blood sugar.

“With sets of experiments the researchers used, they make a very convincing case for that connection,” Dr. Adrian Soto-Mota, a physician-scientist who studies metabolic disease, told The Epoch Times in an email.

Animal studies backed it up. When microbes from statin users were transplanted into healthy mice, the animals developed insulin resistance and lower GLP-1. Restoring the bacteria, or simply adding UDCA, reversed the damage.

“These data are consistent with what is already known,” Nick Norwitz, a Harvard-trained doctor who also holds a doctorate in Metabolism from Oxford, told The Epoch Times.

“Statins are known to increase the risk of Type 2 diabetes. What this study shows is one reason why—they lower GLP-1, a hormone critical for blood sugar and appetite control.”

“These data are consistent with what is already known,” Nick Norwitz, a Harvard-trained doctor who also holds a doctorate in Metabolism from Oxford, told The Epoch Times.

“Statins are known to increase the risk of Type 2 diabetes. What this study shows is one reason why—they lower GLP-1, a hormone critical for blood sugar and appetite control.”

A small pilot study suggested adding UDCA might also be effective in people. Five long-term statin users who took daily UDCA improved their blood sugar, insulin resistance, and GLP-1 levels without losing the cholesterol-lowering benefit.

Other studies point to the same gut connection, showing how microbes regulate GLP-1 and glucose. Statins, it seems, may disrupt that axis in ways few patients—or doctors—realize.

That’s why the findings matter, Dr. Bret Scher, a preventive cardiologist and medical director of the Baszucki Group, told The Epoch Times in an email. “Statins still have a role in treating heart disease and lowering LDL,” he said.

However, to have a real discussion of risks and benefits, doctors should also address insulin resistance and metabolic health—something he said few have been doing.

Other studies point to the same gut connection, showing how microbes regulate GLP-1 and glucose. Statins, it seems, may disrupt that axis in ways few patients—or doctors—realize.

That’s why the findings matter, Dr. Bret Scher, a preventive cardiologist and medical director of the Baszucki Group, told The Epoch Times in an email. “Statins still have a role in treating heart disease and lowering LDL,” he said.

However, to have a real discussion of risks and benefits, doctors should also address insulin resistance and metabolic health—something he said few have been doing.

A little about us: We’re a team of journalists and researchers on a mission to give you REAL and honest information about your health.

Side effects of reading our posts may include: critical thinking.

Follow us for more daily threads—backed by hard data.

—> @EpochHealth

Side effects of reading our posts may include: critical thinking.

Follow us for more daily threads—backed by hard data.

—> @EpochHealth

A Metabolic Paradox

The findings point to an uneasy contradiction. Statins, long praised for protecting the heart, may work against the same hormone that GLP-1 drugs are meant to restore. “I’d call it a metabolic paradox,” Norwitz said.

theepochtimes.com/health/statins…

The findings point to an uneasy contradiction. Statins, long praised for protecting the heart, may work against the same hormone that GLP-1 drugs are meant to restore. “I’d call it a metabolic paradox,” Norwitz said.

theepochtimes.com/health/statins…

Tens of millions take statins for cholesterol, while a rapidly growing number are prescribed GLP-1 drugs for diabetes or weight loss. If one drug blunts the other, patients and doctors need to know.

“It does plausibly explain diabetes risk,” said Soto-Mota. “But biology is rarely about a single switch—there are usually multiple pathways involved.

Even so, he said, the evidence is strong enough to warrant follow-up, especially since so many patients are on both. "It’s important to know if they interact in a way that curbs their potential benefits.”

For now, the overlap of the two remains a question mark with real consequences for millions of patients.

“It does plausibly explain diabetes risk,” said Soto-Mota. “But biology is rarely about a single switch—there are usually multiple pathways involved.

Even so, he said, the evidence is strong enough to warrant follow-up, especially since so many patients are on both. "It’s important to know if they interact in a way that curbs their potential benefits.”

For now, the overlap of the two remains a question mark with real consequences for millions of patients.

Why It Never Reached the Exam Room

Yet despite those stakes, the study has barely made a ripple. Published in a respected, high-impact journal, the findings never entered clinical conversation. When Norwitz asked cardiologists about the effect of statins on GLP-1, most admitted they didn’t know.

That gap, he added, matters for patients. “This should be about informed consent,” he said. In practice, that means giving people enough information to weigh the risks, anticipate side effects, and decide with their doctor what makes sense for them. “These findings open that door.”

Part of the explanation may be where the study appeared. “Cell Metabolism is not a purely clinical journal. It definitely is a top journal (and my favorite journal),” said Soto-Mota. However, most clinicians, he added, follow The New England Journal of Medicine, The Lancet, JAMA, The BMJ, or their specialty journals—so findings in adjacent fields can easily be missed.

Yet despite those stakes, the study has barely made a ripple. Published in a respected, high-impact journal, the findings never entered clinical conversation. When Norwitz asked cardiologists about the effect of statins on GLP-1, most admitted they didn’t know.

That gap, he added, matters for patients. “This should be about informed consent,” he said. In practice, that means giving people enough information to weigh the risks, anticipate side effects, and decide with their doctor what makes sense for them. “These findings open that door.”

Part of the explanation may be where the study appeared. “Cell Metabolism is not a purely clinical journal. It definitely is a top journal (and my favorite journal),” said Soto-Mota. However, most clinicians, he added, follow The New England Journal of Medicine, The Lancet, JAMA, The BMJ, or their specialty journals—so findings in adjacent fields can easily be missed.

Scher said the research should change what patients hear in the exam room. Too often physicians prescribe statins without mentioning their effect on insulin resistance or broader metabolic health, he said.

The oversight is striking given what’s already known. A large 2024 analysis in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology confirmed that statins raise the risk of diabetes, especially at higher doses. What that study didn’t explain was why. The trial published in Cell Metabolism offered one possible answer: a disruption in gut microbes that lowers GLP-1.

For patients already juggling cholesterol and blood sugar, that missing link could be critical. Whether statins blunt the benefits of GLP-1 therapies—or whether a cheap supplement like UDCA could help—remains an open question.

The oversight is striking given what’s already known. A large 2024 analysis in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology confirmed that statins raise the risk of diabetes, especially at higher doses. What that study didn’t explain was why. The trial published in Cell Metabolism offered one possible answer: a disruption in gut microbes that lowers GLP-1.

For patients already juggling cholesterol and blood sugar, that missing link could be critical. Whether statins blunt the benefits of GLP-1 therapies—or whether a cheap supplement like UDCA could help—remains an open question.

Why No One Followed Up

The larger issue, some argue, is how “evidence-based medicine” gets defined. A well-designed trial, even with only a few dozen participants, can reveal important clues. However, unless those findings are confirmed in larger, more expensive studies, they rarely change practice.

“It is perplexing how an important finding like this managed to fly under the radar,” Scher said.

Norwitz was more to the point. “Participant number doesn’t determine quality,” he said. “This was a rigorous trial, yet it hasn’t been followed up or entered clinical discussion. If the system were truly driven by patient need, it would have.”

So why hasn’t anyone taken the next step? The answer, Norwitz suggested, may come down to money. “Who’s going to pay for it?” he asked. “Pfizer isn’t. Not to say Pfizer is evil. They just have no incentive to do it.”

Pfizer developed atorvastatin under the brand name Lipitor—once the world’s best-selling drug. Today, it’s available as a generic made by many companies, but as Norwitz noted, none of them have a financial reason to fund an expensive trial of a cheap supplement.

The larger issue, some argue, is how “evidence-based medicine” gets defined. A well-designed trial, even with only a few dozen participants, can reveal important clues. However, unless those findings are confirmed in larger, more expensive studies, they rarely change practice.

“It is perplexing how an important finding like this managed to fly under the radar,” Scher said.

Norwitz was more to the point. “Participant number doesn’t determine quality,” he said. “This was a rigorous trial, yet it hasn’t been followed up or entered clinical discussion. If the system were truly driven by patient need, it would have.”

So why hasn’t anyone taken the next step? The answer, Norwitz suggested, may come down to money. “Who’s going to pay for it?” he asked. “Pfizer isn’t. Not to say Pfizer is evil. They just have no incentive to do it.”

Pfizer developed atorvastatin under the brand name Lipitor—once the world’s best-selling drug. Today, it’s available as a generic made by many companies, but as Norwitz noted, none of them have a financial reason to fund an expensive trial of a cheap supplement.

The Larger Lesson

For Scher, the takeaway is not just about the drug itself but what patients do alongside it. The study, he said, “clarifies how important it is for everyone on a statin to prioritize their lifestyle for improving and maintaining metabolic health.”

Diet, exercise, and other habits, he added, should be the foundation. “Lifestyle interventions should be the first line treatment,” with supplements like UDCA only considered after an informed discussion with a physician.

“There isn’t one lifestyle, or one way to eat, or one way to exercise,” he added. “A practitioner should work with their patient to find what’s acceptable to them and effective long term.”

For Scher, the takeaway is not just about the drug itself but what patients do alongside it. The study, he said, “clarifies how important it is for everyone on a statin to prioritize their lifestyle for improving and maintaining metabolic health.”

Diet, exercise, and other habits, he added, should be the foundation. “Lifestyle interventions should be the first line treatment,” with supplements like UDCA only considered after an informed discussion with a physician.

“There isn’t one lifestyle, or one way to eat, or one way to exercise,” he added. “A practitioner should work with their patient to find what’s acceptable to them and effective long term.”

Emphasis on lifestyle doesn’t diminish statins’ value. It reframes the conversation, highlighting that powerful drugs work best when paired with daily choices that strengthen the body’s defenses.

The lesson is not to abandon statins, or GLP-1s, or any other drug that can help. It is to demand a system where studies that raise inconvenient questions are pursued, not ignored. Until then, the information patients need may remain in journals that rarely reach the exam room.

“Drugs are tools, but you don’t use a chainsaw to hammer a nail,” said Norwitz. “Patients deserve to know the risks and benefits so they can help choose the right tool for them.”

The lesson is not to abandon statins, or GLP-1s, or any other drug that can help. It is to demand a system where studies that raise inconvenient questions are pursued, not ignored. Until then, the information patients need may remain in journals that rarely reach the exam room.

“Drugs are tools, but you don’t use a chainsaw to hammer a nail,” said Norwitz. “Patients deserve to know the risks and benefits so they can help choose the right tool for them.”

Thanks for reading! If you found this valuable, here's a special deal:

Unlock our ENTIRE library of @EpochHealth articles for just $1/week—plus unlimited access to everything else on our site.

Claim it here:

on.theepochtimes.com/vfox/health?ut…

Unlock our ENTIRE library of @EpochHealth articles for just $1/week—plus unlimited access to everything else on our site.

Claim it here:

on.theepochtimes.com/vfox/health?ut…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh