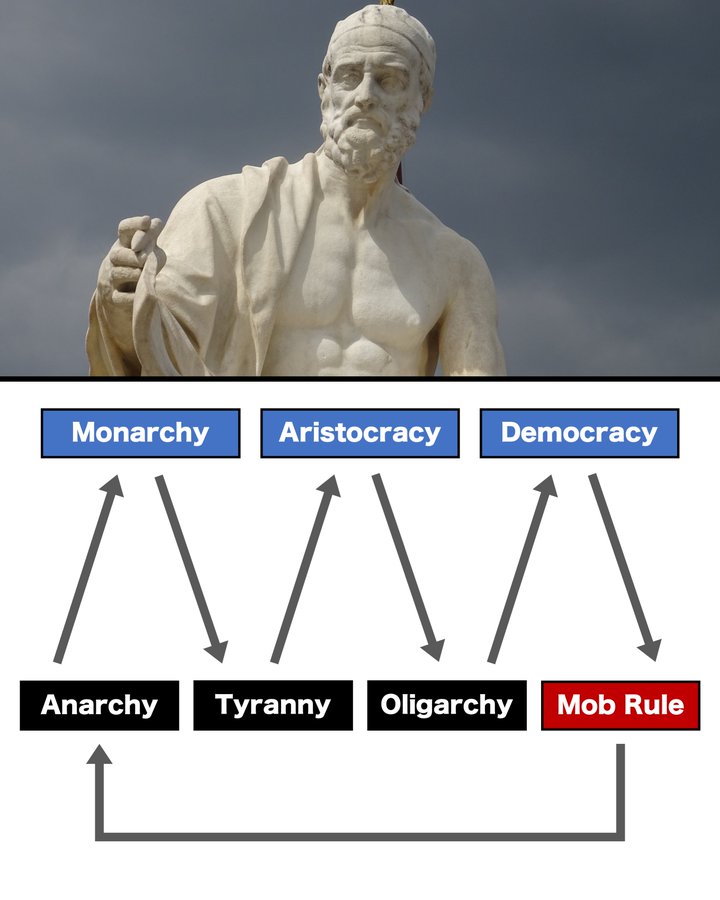

1/ Carl Schmitt stands as one of the few jurists of the twentieth century who grasped that law and politics cannot be separated, that every constitution rests finally on power and decision, not on procedure or neutral principle. Against the illusions of liberalism, which imagine that societies can be governed through rules, balances, and endless discussion, Schmitt insisted that sovereignty is revealed only at the point of rupture, when order is threatened and authority must act without mediation. He called this the state of exception, the moment when the sovereign decides not within the law but over it, and thereby discloses the true foundations of political order.

For Schmitt, liberalism’s dream of a politics reduced to administration was nothing but a form of decay. Parliamentary systems spoke endlessly of rights, freedoms, and humanity, yet in practice they neutralized the state’s capacity to defend the people. By displacing real decisions into endless procedures, they confused weakness for virtue, compromise for wisdom. Schmitt’s diagnosis was not the rant of a reactionary nostalgic for monarchy, nor the fantasy of a utopian revolutionary. It was the sober recognition that politics, in its essence, is conflict, and that no society can endure if it refuses to recognize its enemies, internal or external, and to affirm its own unity against them.

What, then, can we learn from Schmitt? His writings do not hand down a ready-made program, but they reveal truths about political life that no society can escape. They remind us that politics is never settled, that sovereignty cannot be hidden behind procedures, and that a people survives only by affirming itself against those who would undo it.

For Schmitt, liberalism’s dream of a politics reduced to administration was nothing but a form of decay. Parliamentary systems spoke endlessly of rights, freedoms, and humanity, yet in practice they neutralized the state’s capacity to defend the people. By displacing real decisions into endless procedures, they confused weakness for virtue, compromise for wisdom. Schmitt’s diagnosis was not the rant of a reactionary nostalgic for monarchy, nor the fantasy of a utopian revolutionary. It was the sober recognition that politics, in its essence, is conflict, and that no society can endure if it refuses to recognize its enemies, internal or external, and to affirm its own unity against them.

What, then, can we learn from Schmitt? His writings do not hand down a ready-made program, but they reveal truths about political life that no society can escape. They remind us that politics is never settled, that sovereignty cannot be hidden behind procedures, and that a people survives only by affirming itself against those who would undo it.

2/ Schmitt’s first lesson is that conflict cannot be abolished. In “The Concept of the Political” he argued that political life arises from the distinction between friend and enemy, from the ability of a people to recognize those who threaten its existence and to affirm its own being against them. He did not glorify violence, nor did he celebrate war as a positive ideal. His point was sharper: that enmity is a permanent possibility, an irreducible horizon of collective life. No matter how refined institutions become, no matter how elaborate treaties appear, human groups will always find differences they regard as worth defending with their lives. Order itself rests upon acknowledging this fact, for to deny it is to prepare the ground for collapse.

Liberalism denies the permanence of enmity. It dreams of a politics reduced to dialogue, negotiation, and exchange, where all disagreements can be settled by reason or dissolved into tolerance. In practice, this vision erodes the state’s ability to act. A people that refuses to draw boundaries soon discovers that it cannot command loyalty or inspire sacrifice. Where every distinction is blurred, there is nothing left to defend. Such a community is defenseless even against ordinary trials and shatters altogether in moments of crisis. Schmitt’s warning was that politics does not wither away with progress. It endures as long as peoples endure, and when it is forgotten, it returns with greater violence.

Liberalism denies the permanence of enmity. It dreams of a politics reduced to dialogue, negotiation, and exchange, where all disagreements can be settled by reason or dissolved into tolerance. In practice, this vision erodes the state’s ability to act. A people that refuses to draw boundaries soon discovers that it cannot command loyalty or inspire sacrifice. Where every distinction is blurred, there is nothing left to defend. Such a community is defenseless even against ordinary trials and shatters altogether in moments of crisis. Schmitt’s warning was that politics does not wither away with progress. It endures as long as peoples endure, and when it is forgotten, it returns with greater violence.

3/ From the recognition of conflict follows Schmitt’s second lesson, the meaning of sovereignty. In “Political Theology” he defined the sovereign as the one who decides on the exception, the figure who reveals authority not in routine administration but in the moment when order is imperiled. Sovereignty, for Schmitt, is not a matter of legal formulas or constitutional abstractions. It is the living capacity to declare when the law no longer suffices and to act in defense of the political community. Liberal systems recoil from this truth, for they wish to imagine that legality sustains itself, that institutions stand outside the contingencies of history, that peace has become permanent. Yet every crisis exposes the fragility of these illusions. When danger comes, when the foundations of order are shaken, sovereignty is revealed not in texts or procedures but in the decisive act that preserves the state. The sovereign does not speak within the law but over it, and in doing so discloses the ground upon which all constitutions rest.

Schmitt did not attack law as such, nor did he call for arbitrary power. His concern was to remind us of the limits of rules, to show that legal order depends upon a prior authority willing to enforce and, if necessary, to suspend it. Statutes and procedures can regulate daily life, but they cannot defend themselves against forces that deny their validity. In moments of peril, neutrality and delay do not avert conflict but intensify it, for the refusal to decide is itself a decision, one that cedes initiative to others. When the state abdicates sovereignty, partisans within its borders or hostile powers beyond them will seize it for themselves. To recognize the exception, to act when formulas collapse, is therefore the ultimate test of political strength. For Schmitt, this was not a passing observation but the very essence of politics: that every order rests on the will to preserve a people’s existence, and that survival depends not on abstract norms but on the authority to decide when those norms give way.

Schmitt did not attack law as such, nor did he call for arbitrary power. His concern was to remind us of the limits of rules, to show that legal order depends upon a prior authority willing to enforce and, if necessary, to suspend it. Statutes and procedures can regulate daily life, but they cannot defend themselves against forces that deny their validity. In moments of peril, neutrality and delay do not avert conflict but intensify it, for the refusal to decide is itself a decision, one that cedes initiative to others. When the state abdicates sovereignty, partisans within its borders or hostile powers beyond them will seize it for themselves. To recognize the exception, to act when formulas collapse, is therefore the ultimate test of political strength. For Schmitt, this was not a passing observation but the very essence of politics: that every order rests on the will to preserve a people’s existence, and that survival depends not on abstract norms but on the authority to decide when those norms give way.

4/ Schmitt’s third lesson comes from his analysis of parliamentarism. In “The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy,” he showed that the strength of representative institutions had always rested on a background of social unity. Where a people shared language, religion, and custom, their divisions could be debated openly without shattering the cohesion of the state. But when that homogeneity dissolved, parliamentary life became an empty form. Debate no longer aimed at truth or the common good but at the advancement of factions and the bargaining of interests. The chamber that once claimed to refine the will of the people into law degenerated into a theater of rhetoric that concealed decisions already made elsewhere.

Schmitt saw in this decline the fraud of liberal neutrality. Parliaments boasted of openness, of their capacity to reconcile all perspectives, yet in practice they undermined the very unity that made genuine discussion possible. Where voices multiplied without limit, the possibility of persuasion vanished. Agreement could only be reached by trade and compromise, which meant that money and influence carried greater weight than principle or truth. As cynicism spread, authority ebbed, and the state lost its capacity to inspire loyalty. Schmitt’s warning was that parliamentarism, when severed from the substance of a people’s life, becomes not the guardian of liberty but the mask of oligarchy, a stage upon which power hides its face.

Schmitt saw in this decline the fraud of liberal neutrality. Parliaments boasted of openness, of their capacity to reconcile all perspectives, yet in practice they undermined the very unity that made genuine discussion possible. Where voices multiplied without limit, the possibility of persuasion vanished. Agreement could only be reached by trade and compromise, which meant that money and influence carried greater weight than principle or truth. As cynicism spread, authority ebbed, and the state lost its capacity to inspire loyalty. Schmitt’s warning was that parliamentarism, when severed from the substance of a people’s life, becomes not the guardian of liberty but the mask of oligarchy, a stage upon which power hides its face.

5/ In Schmitt’s vision, the state does not exist to arbitrate consumer preferences or to maximize comfort. Its highest task is to embody the unity of a people, to hold within itself the values and traditions for which men are willing to sacrifice. When the state abdicates this role, politics does not vanish but seeps into other domains, into factions, movements, or partisans who seize the right to define enemies and friends in the absence of a sovereign voice. This is why he regarded liberal neutrality as a fraud: the refusal to name an enemy merely leaves the field open for others to do so, often with far more destructive consequences.

He also recognized that no community could be sustained by rational calculation alone. Beyond law and administration, there must be a binding force, a myth that stirs the imagination and commands belief. Liberal societies, with their cult of skepticism and endless relativism, could not provide this. Their rhetoric of humanity was only a mask for economic imperialism, their appeals to universal peace only preludes to more ruthless wars. By contrast, the national myth, however imperfectly realized, at least bound a people to its history, its land, and its destiny. Schmitt grasped that without such a unifying principle, no order could resist dissolution into the formless mass of global commerce and pacifist illusions.

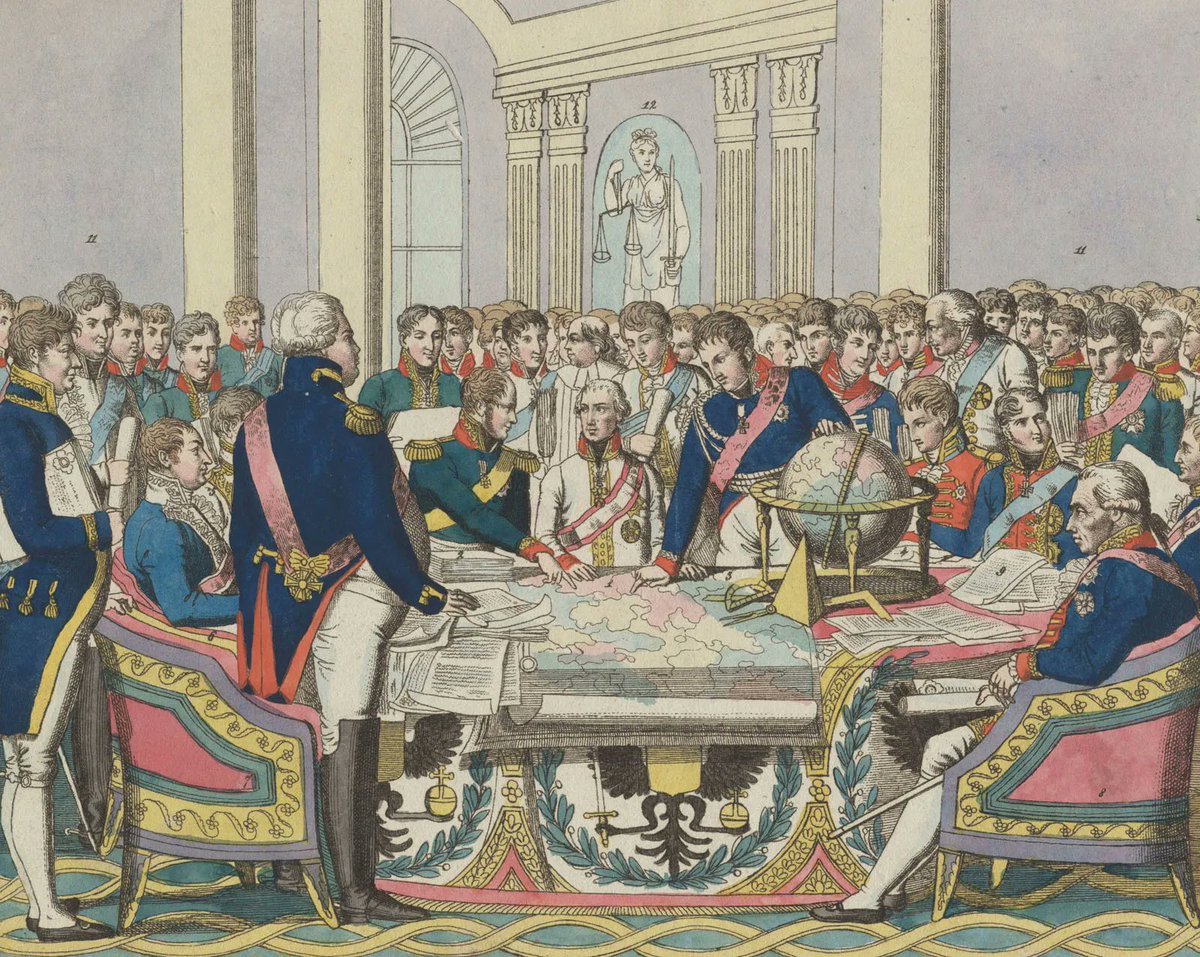

This was the deeper meaning of his critique of Europe’s decline. The jus publicum europaeum, the law of nations that had once regulated war among sovereign states, was collapsing under the weight of humanitarian abstractions. International institutions promised perpetual peace, yet in truth they unleashed a new barbarism in which power was exercised without limits and wars were waged as crusades against inhumanity itself. Europe had abandoned its own political wisdom, preferring the fantasy of moral progress to the hard discipline of sovereignty and balance.

He also recognized that no community could be sustained by rational calculation alone. Beyond law and administration, there must be a binding force, a myth that stirs the imagination and commands belief. Liberal societies, with their cult of skepticism and endless relativism, could not provide this. Their rhetoric of humanity was only a mask for economic imperialism, their appeals to universal peace only preludes to more ruthless wars. By contrast, the national myth, however imperfectly realized, at least bound a people to its history, its land, and its destiny. Schmitt grasped that without such a unifying principle, no order could resist dissolution into the formless mass of global commerce and pacifist illusions.

This was the deeper meaning of his critique of Europe’s decline. The jus publicum europaeum, the law of nations that had once regulated war among sovereign states, was collapsing under the weight of humanitarian abstractions. International institutions promised perpetual peace, yet in truth they unleashed a new barbarism in which power was exercised without limits and wars were waged as crusades against inhumanity itself. Europe had abandoned its own political wisdom, preferring the fantasy of moral progress to the hard discipline of sovereignty and balance.

6/ Schmitt’s enduring lesson is that politics cannot be abolished. It can be denied, it can be forgotten, but it always returns, and when it returns after denial it comes with greater violence. Liberalism tried to dissolve the political into economics, into the mechanical procedures of law, into the abstractions of humanitarian rhetoric. What it created instead was fragility. States lost the ability to defend themselves, parliaments sank into irrelevance, peoples no longer believed in their own endurance. By stripping away illusions of neutrality and progress, Schmitt forced Europe to see that conflict never disappears, that sovereignty cannot be reduced to formulas, and that a community which abandons the principle binding it together prepares the ground for its own dissolution.

To read him today is to confront the same illusions that corroded Europe a century ago, illusions still at work in our own time. The same promises of universal inclusion and perpetual peace continue to erode the foundations of order. The same refusal to name enemies leaves the field to partisans who do so with far greater zeal. Schmitt reminds us that survival depends not on procedures or slogans but on decision and unity, and that every people must be willing to defend its existence against those who would undo it. This is the measure of sovereignty, and this is the truth from which no society can escape.

To read him today is to confront the same illusions that corroded Europe a century ago, illusions still at work in our own time. The same promises of universal inclusion and perpetual peace continue to erode the foundations of order. The same refusal to name enemies leaves the field to partisans who do so with far greater zeal. Schmitt reminds us that survival depends not on procedures or slogans but on decision and unity, and that every people must be willing to defend its existence against those who would undo it. This is the measure of sovereignty, and this is the truth from which no society can escape.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh