A fun thing about Chinese rivers I learned from my research last week:

This map shows the ancient courses of the Yellow River (in blue) and the now-disappeared Ji River (in red). The upper blue line the Yellow route during the Western Han. The lower is its modern path. 🧵

This map shows the ancient courses of the Yellow River (in blue) and the now-disappeared Ji River (in red). The upper blue line the Yellow route during the Western Han. The lower is its modern path. 🧵

Actually, the Western Han route of the Yellow is one of the MANY known routes it has taken over the last 2000 years, as you can see from this image.

From 1128-1855, the Yellow spent 700+ years flowing in an entirely different direction - southeast. During that period, it merged with the Huai River near modern-day Huai'an in Jiangsu, and then traveled northeast again to dump into the ocean. The silt deposits around its estuary pushed the coastline out dozens of kilometers over those 700 years.

From 1128-1855, the Yellow spent 700+ years flowing in an entirely different direction - southeast. During that period, it merged with the Huai River near modern-day Huai'an in Jiangsu, and then traveled northeast again to dump into the ocean. The silt deposits around its estuary pushed the coastline out dozens of kilometers over those 700 years.

That lake system you can see at the bottom of the map above didn't exist at the time. That's Hongze Lake 洪泽湖 (literally: "flood marsh lake") which formed because after the Yellow River's course changed in 1855, the Huai River, lacking the volume of water the Yellow had previously provided, silted up itself, lost its exit to the ocean, formed Hongze Lake, and ended up finding a new outlet connecting south to the Yangtze near Yangzhou, turning the Huai River into a Yangtze tributary, rather then a Yellow tributary.

The Huai only regained its outlet to the ocean in the 1950s when the PRC built the North Jiangsu Main Irrigation Canal.

The Huai only regained its outlet to the ocean in the 1950s when the PRC built the North Jiangsu Main Irrigation Canal.

When the Yellow's 1855 floods happened, it burst its banks in eastern Kaifeng (Henan) and the new route sent it northeast once again into Shandong, overtaking and subsuming portions of both the Daqing River 大清河 and the Ji River 济水.

That's why the map in the first tweet shows the modern Yellow River route only overlapping with a portion of the ancient Ji River route; it some cases it now follows the route of other rivers from the time.

A major downstream portion of the ancient Ji River route is still a flowing waterway today: the Xiaoqing River 小清河 (in red on the map here), which flows east of Jinan parallel to the Yellow River and drains all the smaller rivers to its south in central Shandong. It enters the Bohai Sea independently, south of the Yellow River.

That's why the map in the first tweet shows the modern Yellow River route only overlapping with a portion of the ancient Ji River route; it some cases it now follows the route of other rivers from the time.

A major downstream portion of the ancient Ji River route is still a flowing waterway today: the Xiaoqing River 小清河 (in red on the map here), which flows east of Jinan parallel to the Yellow River and drains all the smaller rivers to its south in central Shandong. It enters the Bohai Sea independently, south of the Yellow River.

But none of those tidbits are the real thing I think it's funny about the Ji River; actually it's this:

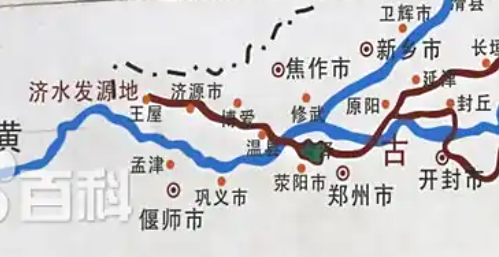

Every map of the Ji River (in red) shows it CROSSING the Yellow River, upstream near Wen County in modern Jiaozuo City. For every Yellow River route.

This is impossible.

Every map of the Ji River (in red) shows it CROSSING the Yellow River, upstream near Wen County in modern Jiaozuo City. For every Yellow River route.

This is impossible.

Rivers can't cross each other - they aren't like highway overpasses! They flow into each other. Thus, if you see such a scenario descrived as a "crossing", one is a tributary, and subsequently a new river (a distributary) is formed on the other side.

But ancient Chinese texts are quite insistent on this matter: the Ji River CROSSES the Yellow River, from north to south. It's even baked into the name: the 济 River, or the "crossing river". So whatever distributary was being formed on the other side, the ancient Chinese believed it was still the Ji River.

Now, keep in mind, the Ji River, flowing down from Wangwu Mountain in modern Jiyuan (literally: "source of the Ji") was fed by groundwater springs and rainfall, so would have been a clear stream. Meanwhile, the Yellow River is famously silty, carrying loess plateau sediment from upstream.

This means that the new distributary formed on the south side of the river also likely would have had to have clear water, for this vision of the Ji River's "crossing" to make sense at all. And they definitely belived the river that flowed into Shandong was still the Ji (e.g., Jinan City, “south of the Ji”).

But ancient Chinese texts are quite insistent on this matter: the Ji River CROSSES the Yellow River, from north to south. It's even baked into the name: the 济 River, or the "crossing river". So whatever distributary was being formed on the other side, the ancient Chinese believed it was still the Ji River.

Now, keep in mind, the Ji River, flowing down from Wangwu Mountain in modern Jiyuan (literally: "source of the Ji") was fed by groundwater springs and rainfall, so would have been a clear stream. Meanwhile, the Yellow River is famously silty, carrying loess plateau sediment from upstream.

This means that the new distributary formed on the south side of the river also likely would have had to have clear water, for this vision of the Ji River's "crossing" to make sense at all. And they definitely belived the river that flowed into Shandong was still the Ji (e.g., Jinan City, “south of the Ji”).

The original Water Classic《水经》written durring the Three Kingdoms period (220-280 CE) doesn't mention the existence of the Ji River on the south bank of the Yellow River at all. It only says the Yan River (沇水) which was the name for the upstream portion of the Ji River, north of the Yellow, flows into the Yellow River.

"济水出河东垣县东王屋山,为沇水"

It was written during a period when the "downstream" section of the Ji River had indeed dried up, and so there was no river on the south side to describe.

But Li Daoyuan, in his Commentary on the Water Classic 《水经注》written sometime in the early 6th century, feels the need to remind his readers that the Ji River enters the Yellow and then exits the Yellow, i.e. "crosses":

"与河合流,又东过成臯县北,又东过荥阳县北,又东至砾溪南,东出过荥泽北"

"After confluence with the Yellow River, it flows eastward past northern Chenggao County, eastward past the northern Xingyang County, then eastward to the south of Li Stream (砾溪), and finally flows out eastward passing north of Xingze Marsh (荥泽).

"济水出河东垣县东王屋山,为沇水"

It was written during a period when the "downstream" section of the Ji River had indeed dried up, and so there was no river on the south side to describe.

But Li Daoyuan, in his Commentary on the Water Classic 《水经注》written sometime in the early 6th century, feels the need to remind his readers that the Ji River enters the Yellow and then exits the Yellow, i.e. "crosses":

"与河合流,又东过成臯县北,又东过荥阳县北,又东至砾溪南,东出过荥泽北"

"After confluence with the Yellow River, it flows eastward past northern Chenggao County, eastward past the northern Xingyang County, then eastward to the south of Li Stream (砾溪), and finally flows out eastward passing north of Xingze Marsh (荥泽).

He follows this with some notes from other ancient texts to back up his assertion:

《释名》曰:济,济也,源出河,北济河而南也。

"In The Explanation of Names it says: Ji means "to cross". Its source is from the Yellow. It traverses north of the Yellow and then goes south."

as well as:

《晋地道志》曰:济自大伾入河,与河水斗,南泆为荥泽。

"The Jin Dynasty Treatise on Geography says: 'The Ji River enters the Yellow at Dapi Mountain; it struggles with Yellow River, and breaks out southward to form the Xingze Marsh."

《释名》曰:济,济也,源出河,北济河而南也。

"In The Explanation of Names it says: Ji means "to cross". Its source is from the Yellow. It traverses north of the Yellow and then goes south."

as well as:

《晋地道志》曰:济自大伾入河,与河水斗,南泆为荥泽。

"The Jin Dynasty Treatise on Geography says: 'The Ji River enters the Yellow at Dapi Mountain; it struggles with Yellow River, and breaks out southward to form the Xingze Marsh."

The Xingze Marsh 荥泽 mentioned here no longer exists, but would have been on the south bank of the Yellow River near modern-day Xingyang City 荥阳市 west of Zhengzhou.

荥泽 is still mentioned all over Xingyang, though, for example Xingze Boulevard and Xingze Hotel.

荥泽 is still mentioned all over Xingyang, though, for example Xingze Boulevard and Xingze Hotel.

So, since Li Daoyuan was certain the Ji River crosses the Yellow River, the mapping convention from then on was to show them crossing.

As for what was actually happening here, there are two plausible explanations for how a clear Ji River "crossed" the Yellow.

As for what was actually happening here, there are two plausible explanations for how a clear Ji River "crossed" the Yellow.

1. The "Ji River" on the north bank was a different river emerging from Xingze Marsh, fed by groundwater springs.

2. The stillness of the Yellow's Xingze Marsh allowed the silt to settle in some parts, with a clear river stream exiting, which was seen as the Ji River.

2. The stillness of the Yellow's Xingze Marsh allowed the silt to settle in some parts, with a clear river stream exiting, which was seen as the Ji River.

Some combination of the two is possible too of course.

But this would explain the compelling visual phenomenon of a clear water river entering the silty Yellow River and then, further downstream, another clear water river exiting via the Xingze Marsh.

But this would explain the compelling visual phenomenon of a clear water river entering the silty Yellow River and then, further downstream, another clear water river exiting via the Xingze Marsh.

Anyway...this was just another fun fact a I picked up from my essay esearch last week.

I actually have enough fun facts to make a whole China Rivers - themed quiz and post it on Sporcle. Maybe I'll do that later...

Here's the essay if you missed it:

feelingthestones.com/p/whats-the-we…

I actually have enough fun facts to make a whole China Rivers - themed quiz and post it on Sporcle. Maybe I'll do that later...

Here's the essay if you missed it:

feelingthestones.com/p/whats-the-we…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh