Here’s exactly how I analyze a real estate deal:

This deal is a perfect example of clear signs you can look out for

This 68-unit deal arrived in my inbox a while ago with 5 massive red flags

This deal is a perfect example of clear signs you can look out for

This 68-unit deal arrived in my inbox a while ago with 5 massive red flags

1. The deal wasn’t listed on loopnet (came straight from a not-that-well-known broker). Means 90%+ of the market didn’t even see it

2. The location was not disclosed in the text of the initial email. Anytime there’s any sort of “effort barrier”, that further reduces the buyer pool

3. The link in the email directed you to an old listing. Another “barrier to entry” and also proof of an incompetent broker

4. The financials provided were horrible. Most notably, the broker underwrote essentially the same rent for the 1-bed and 2-bed units, which is obviously not true. This led to the broker’s proforma revenue being significantly lower than the actual market revenue, which presented an opportunity (most unsophisticated offers came in too low because they were relying on the broker’s numbers)

5. The asset was operating with higher-than-market vacancy with 5 evictions currently in motion (way too many). I know the market and this made it clear the owners were significantly mismanaging the asset

Basically there were clear signs of broker incompetence and owner mis-management. That means the deal is definitely worth looking into

Now let’s get into the deal itself

2. The location was not disclosed in the text of the initial email. Anytime there’s any sort of “effort barrier”, that further reduces the buyer pool

3. The link in the email directed you to an old listing. Another “barrier to entry” and also proof of an incompetent broker

4. The financials provided were horrible. Most notably, the broker underwrote essentially the same rent for the 1-bed and 2-bed units, which is obviously not true. This led to the broker’s proforma revenue being significantly lower than the actual market revenue, which presented an opportunity (most unsophisticated offers came in too low because they were relying on the broker’s numbers)

5. The asset was operating with higher-than-market vacancy with 5 evictions currently in motion (way too many). I know the market and this made it clear the owners were significantly mismanaging the asset

Basically there were clear signs of broker incompetence and owner mis-management. That means the deal is definitely worth looking into

Now let’s get into the deal itself

The Business Plan:

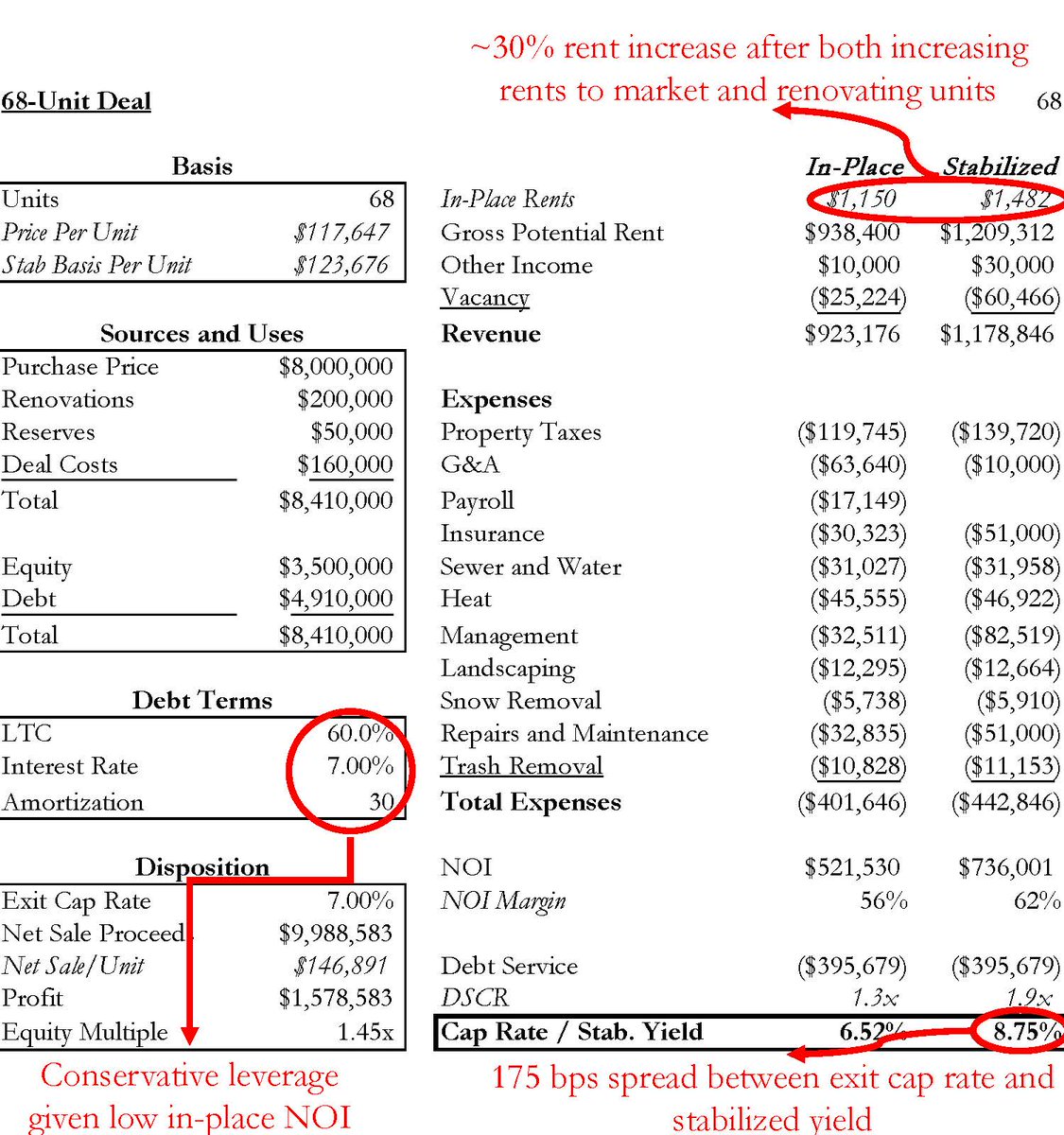

The deal is 68 units, split into 1/3 studios, 1/3 1-beds and 1/3 2-beds. The property is currently half renovated but management hasn’t done a good job of pushing rents

Business plan was to renovate the other 34 units and bring the other units to market, taking the revenue from $900k to $1.2MM and bringing the NOI from $491k to $756k, stabilizing the property at 9.11%, a 211 bps spread from the market cap rate – which would result in $2MM in profit and a 1.6x equity multiple

So the business plan was actually pretty simple. The tough part for this deal was the capitalization (how to structure the debt and equity). The deal was underwritten with a 60% LTV, 7% interest rate loan. Why’s that?

For a deal like this (where the in-place income is relatively low compared to the purchase price), you have to be a bit creative with the capitalization

The deal is 68 units, split into 1/3 studios, 1/3 1-beds and 1/3 2-beds. The property is currently half renovated but management hasn’t done a good job of pushing rents

Business plan was to renovate the other 34 units and bring the other units to market, taking the revenue from $900k to $1.2MM and bringing the NOI from $491k to $756k, stabilizing the property at 9.11%, a 211 bps spread from the market cap rate – which would result in $2MM in profit and a 1.6x equity multiple

So the business plan was actually pretty simple. The tough part for this deal was the capitalization (how to structure the debt and equity). The deal was underwritten with a 60% LTV, 7% interest rate loan. Why’s that?

For a deal like this (where the in-place income is relatively low compared to the purchase price), you have to be a bit creative with the capitalization

You basically have 3 options:

1. Use high leverage bridge debt to fund the renovations

2. Use a low leverage bank loan and fund the renovations through equity

3. Increase the rents gradually and fund the renovations with cashflow

1. Use high leverage bridge debt to fund the renovations

2. Use a low leverage bank loan and fund the renovations through equity

3. Increase the rents gradually and fund the renovations with cashflow

The problem with bridge debt is that it involves high leverage which drastically increases the risk of the deal. The problem with a low leverage bank loan and funding the renovations through equity is that it requires a huge amount of equity, which kills your returns

So how to solve this problem? I like to use a hybrid structure.

In this case, there are 68 total units and half of them have already been renovated by the current owners. I operate in the market and know that renovations should cost roughly $20k/unit. 68 units / 2 = 34 units left to renovate. 34 units * $20k/unit in renovations = $680k in total renovation dollars needed

As you can see, only $200k of renovation dollars have been funded up front

So where’s the rest coming from? Cashflow

So how to solve this problem? I like to use a hybrid structure.

In this case, there are 68 total units and half of them have already been renovated by the current owners. I operate in the market and know that renovations should cost roughly $20k/unit. 68 units / 2 = 34 units left to renovate. 34 units * $20k/unit in renovations = $680k in total renovation dollars needed

As you can see, only $200k of renovation dollars have been funded up front

So where’s the rest coming from? Cashflow

The year 1 cashflow isn’t much (roughly $100k, NOI minus debt service). But the rents are well below market and there are 10 units we can renovate immediately ($200k renovation dollars/$20k per unit)

So by the end of year 1, 44 of the units would be fully renovated and the unrenovated units would be marked to market. That would bring the yearly cashflow to $200k-$300k

Then we would simply take the cashflow from the property and reinvest it into unit renovations every time a unit turns

Assuming cashflow was $250k/year after year 1, we’d be able to complete the renovations in 2 years and be ready to sell by the end of year 3

Very simple business plan but requires creativity to get it done.

This deal would never work if you weren’t able to be creative with the renovation funding

If you funded it through bridge debt it would require far too much risk. If you funded it through equity, it would require far too much equity, which would make the returns not worth it. So being creative is important

The last part to address about the business plan is the expenses. I’m sure I’ll get a dozen replies about how you “can’t run a lower expense load than the seller” from all the geniuses in the comments

There is zero reason why your G&A on a 68-unit building should be $63k. Even $10k (which I changed it to) is high. There’s simply not much overhead. Properties in this market should run at approximately a 65% NOI margin, which this asset is now hitting in the underwriting.

So by the end of year 1, 44 of the units would be fully renovated and the unrenovated units would be marked to market. That would bring the yearly cashflow to $200k-$300k

Then we would simply take the cashflow from the property and reinvest it into unit renovations every time a unit turns

Assuming cashflow was $250k/year after year 1, we’d be able to complete the renovations in 2 years and be ready to sell by the end of year 3

Very simple business plan but requires creativity to get it done.

This deal would never work if you weren’t able to be creative with the renovation funding

If you funded it through bridge debt it would require far too much risk. If you funded it through equity, it would require far too much equity, which would make the returns not worth it. So being creative is important

The last part to address about the business plan is the expenses. I’m sure I’ll get a dozen replies about how you “can’t run a lower expense load than the seller” from all the geniuses in the comments

There is zero reason why your G&A on a 68-unit building should be $63k. Even $10k (which I changed it to) is high. There’s simply not much overhead. Properties in this market should run at approximately a 65% NOI margin, which this asset is now hitting in the underwriting.

Deal Result:

After some back and forth, I maxed out my bid at $8MM. The winning bid was $8.3MM, which I simply wasn’t willing to go up to

The stabilized yield at $8MM was 9.11%. The stabilized yield at $8.3MM was 8.73%, which is below the 200bps spread (that I shoot for at minimum) between the market cap rate of 7% and the stabilized yield. Given that $8MM was already higher than I would’ve liked (I liked the deal far more at $7.6MM, almost a 10% stabilized yield) it didn’t make much sense to chase this deal

The real killer though is at an $8.3MM purchase price, the equity multiple drops from 1.6x to 1.4x. 3 years of work renovating 34 units just to get a 40% return on your money? Not great and not worth it. Better opportunities out there

Overall though, the bid-ask spread between buyers and sellers is getting tighter, which is very good. In this case, I was only ~4% off ($300k off) getting under contract on a deal with a 200bps+ spread between the stabilized yield and the market cap rate

A year ago I was regularly 20% off from a 200bps spread

Sellers are coming back to reality, which means there will very likely be great deals to be had on the horizon

// If you want to buy your own deals and make real money in real estate

Apply in the next post for the Acquisitions Bootcamp to work 1-on-1 with me

If you don’t have a deal within 2 months, I will work for free until you do //

After some back and forth, I maxed out my bid at $8MM. The winning bid was $8.3MM, which I simply wasn’t willing to go up to

The stabilized yield at $8MM was 9.11%. The stabilized yield at $8.3MM was 8.73%, which is below the 200bps spread (that I shoot for at minimum) between the market cap rate of 7% and the stabilized yield. Given that $8MM was already higher than I would’ve liked (I liked the deal far more at $7.6MM, almost a 10% stabilized yield) it didn’t make much sense to chase this deal

The real killer though is at an $8.3MM purchase price, the equity multiple drops from 1.6x to 1.4x. 3 years of work renovating 34 units just to get a 40% return on your money? Not great and not worth it. Better opportunities out there

Overall though, the bid-ask spread between buyers and sellers is getting tighter, which is very good. In this case, I was only ~4% off ($300k off) getting under contract on a deal with a 200bps+ spread between the stabilized yield and the market cap rate

A year ago I was regularly 20% off from a 200bps spread

Sellers are coming back to reality, which means there will very likely be great deals to be had on the horizon

// If you want to buy your own deals and make real money in real estate

Apply in the next post for the Acquisitions Bootcamp to work 1-on-1 with me

If you don’t have a deal within 2 months, I will work for free until you do //

Acquisitions Bootcamp is an 8-week program where you work 1-on-1 with me to craft an investment strategy to fit your skillset, resources & goals - & then find you a deal to fit that strategy

Limited spots available

Apply below

calendly.com/realestategod/…

Limited spots available

Apply below

calendly.com/realestategod/…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh