1/In the Eurozone, unconventional monetary policy leads to large cross-border fiscal transfers because it allows the periphery to borrow from the core at belo-market rates. We quantify these transfers.

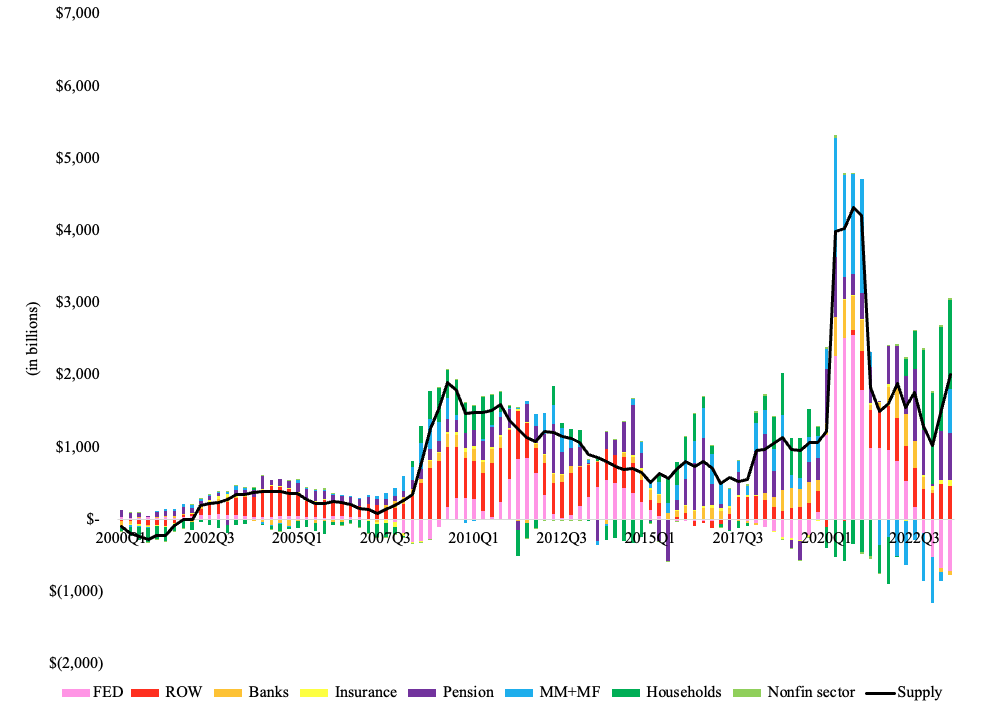

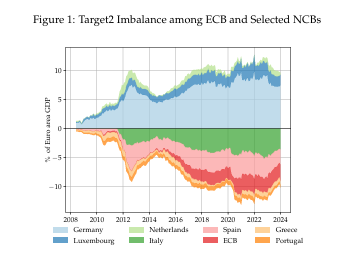

2/ The Eurosystem’s balance sheet had grown to 56% of GDP in the Eurozone by the end of 2021. Most of this growth has happened through an expansion of the national central bank (NCB) balance sheets, because NCBs carry out 90% of the asset purchases. The ECB funds its asset purchases mostly by issuing bank reserves in core countries. The NCBs of core countries accumulate claims on the NCBs of periphery countries intermediated by the ECB.2 These intra-Eurozone claims are referred to as Target2 assets and liabilities.

For example, between 2014 and 2021, the Bundesbank has funded its balance sheet expansion mainly by issuing bank reserves, while the Banca d’Italia has done so by issuing Target2 IOUs.

For example, between 2014 and 2021, the Bundesbank has funded its balance sheet expansion mainly by issuing bank reserves, while the Banca d’Italia has done so by issuing Target2 IOUs.

3/Whenever the ECB expands its balance sheet, the Eurozone periphery borrows from the core through the Eurosystem at a low rate below the market rate.

For these Target2 claims to be truly risk-free, the ECB must be the senior creditor, but, in that case, the government bonds of periphery countries would be rendered riskier by large-asset scale purchases, since bondholders have been effectively subordinated to the ECB. Existing empirical evidence implies that QE in the Eurozone lowers yields spreads by reducing credit risk. This evidence from bond market suggests that Target2 claims are directly exposed to default and redenomination risk in the perception of bond investors.

For these Target2 claims to be truly risk-free, the ECB must be the senior creditor, but, in that case, the government bonds of periphery countries would be rendered riskier by large-asset scale purchases, since bondholders have been effectively subordinated to the ECB. Existing empirical evidence implies that QE in the Eurozone lowers yields spreads by reducing credit risk. This evidence from bond market suggests that Target2 claims are directly exposed to default and redenomination risk in the perception of bond investors.

4/As these balance sheet expansions are concentrated in times of stress in bond markets, taxpayers in core countries like Germany are likely to be exposed to credit and currency risk—on the asset side of the Bundesbank—in high risk episodes, but they are not compensated for this risk. The ECB pools the income net of expenses earned by the NCBs on their balance sheets, and then redistributes the pooled income back to NCBs based on their capital key shares. Each NCB’s holding of its domestic sovereign debt is exempt from the pooling arrangement. As a result, NCBs in the periphery can borrow at low interest rates from the core to earn the carry profit on its own high-risk sovereign bonds.

5/This core-periphery pattern is an equilibrium phenomenon whenever investors impute a non-zero probability to a break-up of the Eurozone. All else equal, Eurozone banks will strictly prefer to hold reserves in the core countries, because core currencies would be expected to appreciate against periphery currencies in case of a Eurozone exit or break-up. As a result, bank reserves in the core and the periphery should not trade at par. Given that they do in the Eurosystem, banks strictly prefer to hold core reserves in equilibrium. Similarly, households strictly prefer to hold cashinthecorecountries. To the best of our knowledge, oursisthefirstpapertoarguethat this core-periphery pattern is an equilibrium phenomenon. This evidence from reserve accumulation in the core suggests that reserves in the periphery are exposed to currency redenomination risk.

6/To quantify the implicit transfers due to income pooling, we compare the income from the pooling arrangement to a counterfactual scenario without Eurozone, without the ECB pooling arrangements and without non-marketable debt. In this counterfactual scenario, NCBs do not 2pool the income, and assets earn market rates of return. We assume that theEurozone governments only borrow from other Eurozone governments at the prevailing market rates. We impute NCB incomes and expenses based on these assumptions. Importantly, we do not assume that Target2 claims are as risky as government bond

Over this period between 2014 and 2023, Germany paid a cross-border transfer of 11% of GDP to other counties, while Italy and Spain received a cross-border subsidy of 5.9% and 7.2% of their GDP, respectively. However, Italian and Spanish taxpayers receive only a smaller cumulative net subsidy of 2.6% and 2.1% of their GDP in the same period, because part of the cross-border transfers accrue to Italian and Spanish banks, not taxpayers. When accounting for all NCBs and ECB, cross-country subsidies sum to zero.

The red lines are the cross-country subsidies.

Over this period between 2014 and 2023, Germany paid a cross-border transfer of 11% of GDP to other counties, while Italy and Spain received a cross-border subsidy of 5.9% and 7.2% of their GDP, respectively. However, Italian and Spanish taxpayers receive only a smaller cumulative net subsidy of 2.6% and 2.1% of their GDP in the same period, because part of the cross-border transfers accrue to Italian and Spanish banks, not taxpayers. When accounting for all NCBs and ECB, cross-country subsidies sum to zero.

The red lines are the cross-country subsidies.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh