Economist at Stanford. Fascinated by exchange rates. Really wanted to be a pilot. Check out my substack with Romain Wacziarg https://t.co/UYmP4HjRs8.

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

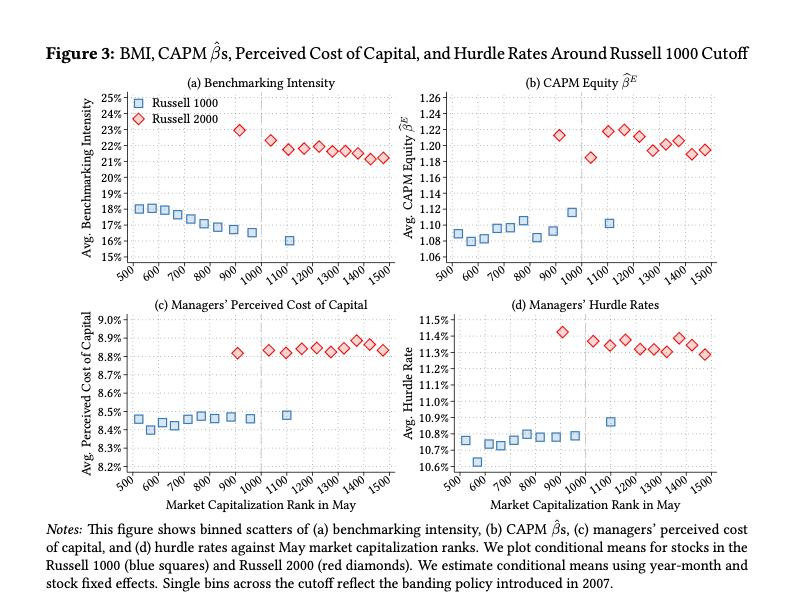

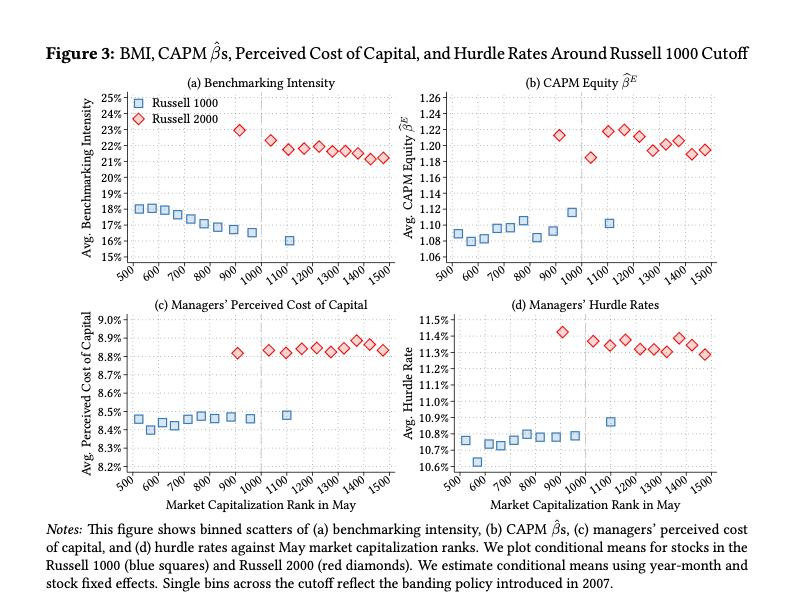

2/Chris and Sebastian how that higher benchmarking intensity (i.e., more passive money invested in your stock) seems to translate into higher betas for your stock, even thought the riskiness of the cash flows has not changed.

2/Chris and Sebastian how that higher benchmarking intensity (i.e., more passive money invested in your stock) seems to translate into higher betas for your stock, even thought the riskiness of the cash flows has not changed.

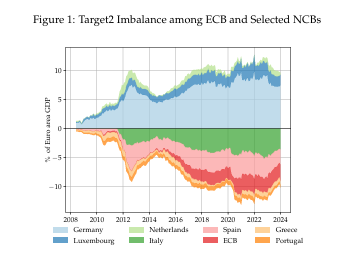

2/ The Eurosystem’s balance sheet had grown to 56% of GDP in the Eurozone by the end of 2021. Most of this growth has happened through an expansion of the national central bank (NCB) balance sheets, because NCBs carry out 90% of the asset purchases. The ECB funds its asset purchases mostly by issuing bank reserves in core countries. The NCBs of core countries accumulate claims on the NCBs of periphery countries intermediated by the ECB.2 These intra-Eurozone claims are referred to as Target2 assets and liabilities.

2/ The Eurosystem’s balance sheet had grown to 56% of GDP in the Eurozone by the end of 2021. Most of this growth has happened through an expansion of the national central bank (NCB) balance sheets, because NCBs carry out 90% of the asset purchases. The ECB funds its asset purchases mostly by issuing bank reserves in core countries. The NCBs of core countries accumulate claims on the NCBs of periphery countries intermediated by the ECB.2 These intra-Eurozone claims are referred to as Target2 assets and liabilities.

1/ On April 2, President Trump announced the reciprocal tariffs to be imposed on a long list of countries. On April 4 China retaliated. The VIX, a measure of implied volatility in the US stock market, more than doubled and peaked at 52 on April 8, 2025, up from 21 on April 2. This means that stock investors estimated the annualized volatility of S&P 500 stock returns to be around 52% per annum. Between April 4 and April 14, the US dollar depreciated by 3.6%. The depreciation of the dollar was surprising to market participants. Normally, in times of global volatility, such as during the GFC of 2008 and the onset of the pandemic in March of 2020, the dollar appreciates as dollar-denominated assets benefit from a flight to safety. Not this time around.

1/ On April 2, President Trump announced the reciprocal tariffs to be imposed on a long list of countries. On April 4 China retaliated. The VIX, a measure of implied volatility in the US stock market, more than doubled and peaked at 52 on April 8, 2025, up from 21 on April 2. This means that stock investors estimated the annualized volatility of S&P 500 stock returns to be around 52% per annum. Between April 4 and April 14, the US dollar depreciated by 3.6%. The depreciation of the dollar was surprising to market participants. Normally, in times of global volatility, such as during the GFC of 2008 and the onset of the pandemic in March of 2020, the dollar appreciates as dollar-denominated assets benefit from a flight to safety. Not this time around.

2/For the past 75 years The US has been the global safe asset supplier. And that’s a great position to be in.

2/For the past 75 years The US has been the global safe asset supplier. And that’s a great position to be in.

2/But until last year, there was broad-based fiscal exuberance in the US. Not just the “Learn to love trillion dollar deficits” variety of the Modern Monetary Theory fringes.

2/But until last year, there was broad-based fiscal exuberance in the US. Not just the “Learn to love trillion dollar deficits” variety of the Modern Monetary Theory fringes.

https://twitter.com/jasonfurman/status/1707210043022594171

2/The losses matter. If you consolidate the Fed and the Treasury, then QE has shortened the duration of the government's IOUs. The mark-to-market losses measure the cost to taxpayers of shortening duration and not locking in longer rates.

2/The losses matter. If you consolidate the Fed and the Treasury, then QE has shortened the duration of the government's IOUs. The mark-to-market losses measure the cost to taxpayers of shortening duration and not locking in longer rates. https://twitter.com/HannoLustig/status/1641828804007014400

2/Ratio of equity capital to total assets for shadow banks and traditional banks. Density plotted below.

2/Ratio of equity capital to total assets for shadow banks and traditional banks. Density plotted below.

2/ The UK also converted 5% war loans from WW-I into 3.5% coupon bonds in 1932, to deal with a sovereign debt crisis. Some might call that sovereign debt restructuring. See for example https://t.co/KPiNhyxxgzft.com/content/e586cd…

2/ The UK also converted 5% war loans from WW-I into 3.5% coupon bonds in 1932, to deal with a sovereign debt crisis. Some might call that sovereign debt restructuring. See for example https://t.co/KPiNhyxxgzft.com/content/e586cd…

https://twitter.com/nberpubs/status/16809576250206986271/Draghi (correctly imo) credits the promise of implicit transfers backing all Eurozone debt before 2008 for the low spreads. All sovereign debt was pretty much priced identically in the Eurozone pre-GFC.

1/ Taxpayers should not be asked to subsidize the carry trade. We already know from work by my colleague @JulianeBegenau with @piazzesi and Schneider that banks don't seem to use derivatives to hedge their interest rate risk exposure.

1/ Taxpayers should not be asked to subsidize the carry trade. We already know from work by my colleague @JulianeBegenau with @piazzesi and Schneider that banks don't seem to use derivatives to hedge their interest rate risk exposure.

https://twitter.com/HannoLustig/status/16350721192636006412/Not a bad model for SVB, which had a $117 portfolio of Agency MBS and long-dated Treasurys with a duration of 5.6 years. But SVB was only marking-to-market $26 billion of this portfolio. The rest was designated hold-to-maturity (or close-your-eyes).

https://twitter.com/HannoLustig/status/1635072121264291840

2/same pattern for projected deficits up to 10 years out. Too optimistic since 2000. Consistently.

2/same pattern for projected deficits up to 10 years out. Too optimistic since 2000. Consistently.

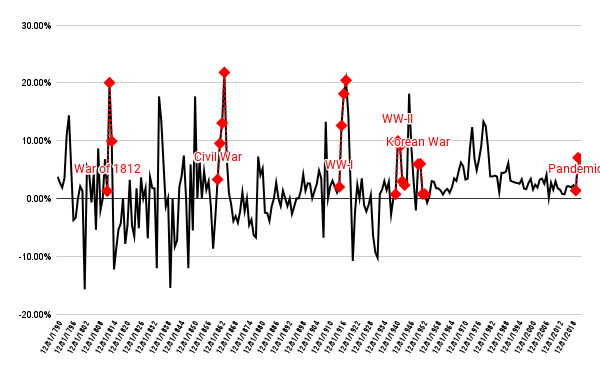

2/The US government has almost always resorted to some inflation during and after large wars, shifting some of the burden from taxpayers to bondholders. YoY inflation.

2/The US government has almost always resorted to some inflation during and after large wars, shifting some of the burden from taxpayers to bondholders. YoY inflation.

https://twitter.com/klaus_adam/status/16029389495587471381/The ECB is now in the business of using its balance sheet as a warehouse for risks that private investors do not want to hold at current prices. ECB has completely crowded out private investors in some markets.

1/if you create a currency that is not a hedge against risk and it does not provide meaningful liquidity/safety services, then investors will simply equate the long-run return on your currency with that of other currencies

1/if you create a currency that is not a hedge against risk and it does not provide meaningful liquidity/safety services, then investors will simply equate the long-run return on your currency with that of other currencies

https://twitter.com/ChrisGiles_/status/15802722824709980171/defined benefit pension funds in the UK (PFs) are forced to mark their liabilities to market using the gilt yield curve. when the BoE buys gilts on Tuesday and the 30-year yield declines, the PDV of the PF's future payouts increases