We have all seen the email below, but what do it mean?

What are factoring facilities? And what is going on here?

1) Factoring Basics

2) Dummy Example

3) Common Factoring Structures

4) Reasons for Factoring

5) The infamous Weil email explained

What are factoring facilities? And what is going on here?

1) Factoring Basics

2) Dummy Example

3) Common Factoring Structures

4) Reasons for Factoring

5) The infamous Weil email explained

1) Factoring Basics

Factoring is a form of financing that allows companies to convert their accounts receivable into immediate cash.

Traditionally, when a company sells goods or services, it issues an invoice to its customer, which is often not paid for thirty, sixty, or even ninety days. Instead of waiting for the cash payment, some companies opt to sell the invoice to a third party, known as a “factor”, at a discount, typically around 95 to 98% of the receivables face value (this discount represents the fee charged by the factor).

Importantly, factors often won’t advance the entire cash balance upfront. Typically, 75% to 90% of the receivable’s face value is advanced upfront, and the remaining balance is transferred, less the abovementioned discount, once customer accounts have been collected.

Therefore, once the customer has paid the invoice, the operating company will have collected the full receivables balance, less the factoring fee.

The Factor’s fee represents its earnings for providing upfront liquidity and assuming the risk that the customer may not pay on time, or at all.

Factoring is a form of financing that allows companies to convert their accounts receivable into immediate cash.

Traditionally, when a company sells goods or services, it issues an invoice to its customer, which is often not paid for thirty, sixty, or even ninety days. Instead of waiting for the cash payment, some companies opt to sell the invoice to a third party, known as a “factor”, at a discount, typically around 95 to 98% of the receivables face value (this discount represents the fee charged by the factor).

Importantly, factors often won’t advance the entire cash balance upfront. Typically, 75% to 90% of the receivable’s face value is advanced upfront, and the remaining balance is transferred, less the abovementioned discount, once customer accounts have been collected.

Therefore, once the customer has paid the invoice, the operating company will have collected the full receivables balance, less the factoring fee.

The Factor’s fee represents its earnings for providing upfront liquidity and assuming the risk that the customer may not pay on time, or at all.

2) Dummy Example

To numerically illustrate concepts, we’ll use ABC Co. as a hypothetical example.

First, imagine ABC Co. sells $100k worth of goods to a customer on sixty-day terms. Instead of waiting two months to collect, ABC Co. sells the invoice to Factor Co.

On the day of the sale, Factor Co. advances 85% of the invoice, or $85,000, to ABC Co.

When the customer eventually pays the full $100,000 on day 60, Factor Co. sends the remaining $15,000 back to ABC Co., but subtracts its $3,000 factoring fee.

In total, ABC Co. has collected $97,000, with $85,000 upfront and $12,000 later, with the $3,000 difference in cash collected and face value representing the cost of accelerating cash flow.

To numerically illustrate concepts, we’ll use ABC Co. as a hypothetical example.

First, imagine ABC Co. sells $100k worth of goods to a customer on sixty-day terms. Instead of waiting two months to collect, ABC Co. sells the invoice to Factor Co.

On the day of the sale, Factor Co. advances 85% of the invoice, or $85,000, to ABC Co.

When the customer eventually pays the full $100,000 on day 60, Factor Co. sends the remaining $15,000 back to ABC Co., but subtracts its $3,000 factoring fee.

In total, ABC Co. has collected $97,000, with $85,000 upfront and $12,000 later, with the $3,000 difference in cash collected and face value representing the cost of accelerating cash flow.

3) Common Factoring Structures

Although the basic idea of factoring is simple, facilities can be structured in several different ways, depending on the borrower's needs and the factor’s risk tolerance:

Notification vs. Non-Notification:

First, a factoring arrangement can be a notification or non-notification agreement. In a notification deal, the customer is explicitly informed that its invoice has been sold and is directed to pay the Factor rather than the operating entity. This makes receivable collection straightforward and reduces the risk of misdirected payments. In a non-notification deal, the customer is never told that the receivable has been factored and continues to pay the operating company as though nothing has changed.

When customers pay the operating company, cash collected from factored invoices is typically held in segregated accounts before quickly being upstreamed to the factoring company. Tight cash management controls become extremely important down the line, when considering the accounting and legal treatment of factoring facilities.

Non-notification structures are attractive to companies that want to keep their financing structures out of customer view, but they also expose the Factor to more risk since cash flows through the company before reaching them.

Each structure carries its own benefits, and both are common, with notification factoring often being utilized by middle-market companies and non-notification being utilized by large or sponsor-backed companies.

Regular vs. Spot:

Factoring can also be arranged on a regular or “spot” basis. In a spot deal, like the ABC Co. example above, the company and Factor agree on a one-off transaction, selling a single receivable or a small batch.

This might be done to address a one-off short-term liquidity pinch. Companies might also use spot arrangements when confidentiality or customer relationships are a concern. For example, a company that is limited to a notification structure might only factor receivables of select customers. On the other hand, a regular factoring deal functions more like a revolving credit facility.

The company and Factor will maintain an ongoing relationship and have an approved limit, which can be drawn and repaid. Regular factoring programs are more common among all types of companies, as they are cheaper and more easily integrated over the longer term. Conversely, spot factoring may be a viable option for small businesses that need immediate cash against specific invoices (e.g., a $100k sale to Walmart that won’t pay for 60+ days).

Recourse vs. Non-Recourse Factoring:

The last and most important distinction is whether the factoring agreement is recourse or non-recourse. In a recourse arrangement, if the customer fails to pay the factor, the Factor may demand repayment from the operating company.

Economically, that puts the customer’s credit risk back on the company, making the transaction seem more like an RCF or ABL facility. In contrast, the Factor bears this customer credit risk in a non-recourse deal, under which the Factor bears any loss from non-payment.

Due to this shift in risk, non-recourse factoring arrangements almost always feature higher fees than recourse deals. Non-recourse deals are also much more likely to qualify as a “true sale”.

Although the basic idea of factoring is simple, facilities can be structured in several different ways, depending on the borrower's needs and the factor’s risk tolerance:

Notification vs. Non-Notification:

First, a factoring arrangement can be a notification or non-notification agreement. In a notification deal, the customer is explicitly informed that its invoice has been sold and is directed to pay the Factor rather than the operating entity. This makes receivable collection straightforward and reduces the risk of misdirected payments. In a non-notification deal, the customer is never told that the receivable has been factored and continues to pay the operating company as though nothing has changed.

When customers pay the operating company, cash collected from factored invoices is typically held in segregated accounts before quickly being upstreamed to the factoring company. Tight cash management controls become extremely important down the line, when considering the accounting and legal treatment of factoring facilities.

Non-notification structures are attractive to companies that want to keep their financing structures out of customer view, but they also expose the Factor to more risk since cash flows through the company before reaching them.

Each structure carries its own benefits, and both are common, with notification factoring often being utilized by middle-market companies and non-notification being utilized by large or sponsor-backed companies.

Regular vs. Spot:

Factoring can also be arranged on a regular or “spot” basis. In a spot deal, like the ABC Co. example above, the company and Factor agree on a one-off transaction, selling a single receivable or a small batch.

This might be done to address a one-off short-term liquidity pinch. Companies might also use spot arrangements when confidentiality or customer relationships are a concern. For example, a company that is limited to a notification structure might only factor receivables of select customers. On the other hand, a regular factoring deal functions more like a revolving credit facility.

The company and Factor will maintain an ongoing relationship and have an approved limit, which can be drawn and repaid. Regular factoring programs are more common among all types of companies, as they are cheaper and more easily integrated over the longer term. Conversely, spot factoring may be a viable option for small businesses that need immediate cash against specific invoices (e.g., a $100k sale to Walmart that won’t pay for 60+ days).

Recourse vs. Non-Recourse Factoring:

The last and most important distinction is whether the factoring agreement is recourse or non-recourse. In a recourse arrangement, if the customer fails to pay the factor, the Factor may demand repayment from the operating company.

Economically, that puts the customer’s credit risk back on the company, making the transaction seem more like an RCF or ABL facility. In contrast, the Factor bears this customer credit risk in a non-recourse deal, under which the Factor bears any loss from non-payment.

Due to this shift in risk, non-recourse factoring arrangements almost always feature higher fees than recourse deals. Non-recourse deals are also much more likely to qualify as a “true sale”.

4) Reasons for Factoring

To understand why companies use factoring facilities, we’ll return to ABC Co., covering two primary use cases.

The first and more intuitive use case is working capital management. Imagine that ABC Co. is a middle-market supplier of specialty cleaning products, selling primarily into big box retail, with Walmart accounting for more than 50% of its sales. Like most large retailers, Walmart is able to leverage its scale and bargaining power to negotiate extended payment terms, often 9060+ days, leaving smaller vendors like ABC Co. waiting for months to collect cash.

On the other hand, ABC Co. must pay its own suppliers within 30 days and cover payroll every two weeks. The result is cash flowing out faster than it comes in. By factoring its receivables, ABC Co. is able to accelerate cash receipts from its invoices upfront to cover current working capital needs.

Why doesn’t ABC Co. just borrow on a revolving line of credit?

For companies like ABC Co., factoring functions as a reasonable alternative or supplement to a revolving credit facility. This is because factoring “piggybacks” on the credit quality of ABC Co.’s buyers, which in this case are large investment-grade retailers, rather than its own. This allows for quicker and easier access to capital.

The second use case relates to a company’s leverage optics. Even when a company has adequate liquidity, the accounting treatment of factoring can make it an appealing tool for managing leverage-related metrics.

The clearest example of this is net debt-to-EBITDA. In a true sale arrangement, cash is received, but there is no corresponding liability recorded, representing a dollar-for-dollar decrease in net leverage and no change in total leverage.

This creates a rare and interesting dynamic where a company can raise liquidity while simultaneously lowering reported net leverage, as the cash inflow from factoring is essentially treated as a cash flow from operations rather than financing.

On the other hand, if the company were to borrow via an RCF, cash would increase, but so would debt, leaving net debt the same and increasing total debt.

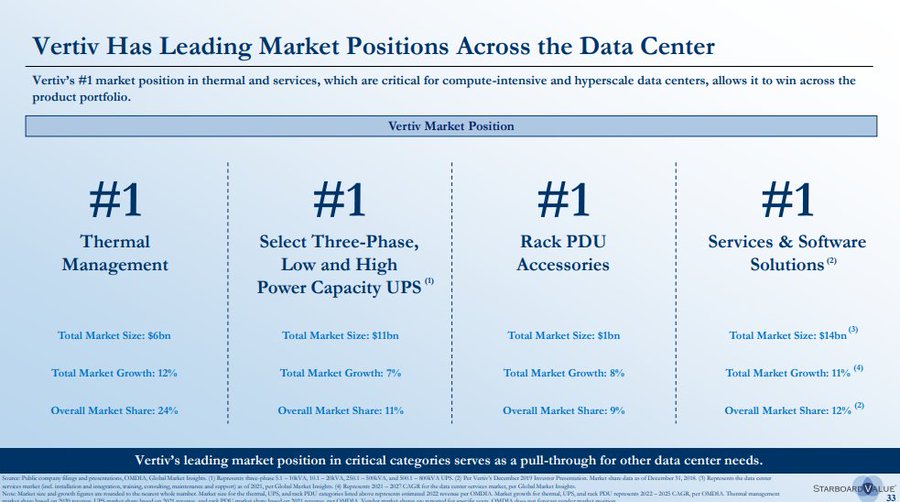

To illustrate this dynamic, imagine ABC Co. now has a balance sheet with $150mm of outstanding receivables and a covenant limiting total debt to EBITDA of 4x. The company is facing a short-term working capital squeeze following a seasonal inventory build and delayed collections from its Walmart. To fund operations, management considers two options: drawing $30mm on its revolving credit facility or factoring $30mm of receivables under a non-recourse true-sale arrangement. ABC Co.’s pre-transaction balance sheet is presented below:

With $290mm of total debt, representing 3.6x EBITDA, ABC Co. sits just below its 4.0x maximum covenant threshold. With only $20mm of cash on hand, the company expects a temporary working-capital shortfall, as payments come due before collections from its major retail customers.

Under the first option, which is detailed above, ABC Co. draws $30mm from its revolver to fund payables. While this immediately increases cash, it also raises total debt to $320mm, pushing leverage to its maximum limit of 4.0x. Any additional borrowing or decline in EBITDA would push leverage above its limit. While an RCF draw solves ABC Co.’s liquidity problem, it presents the new issue of lender scrutiny.

Under the second option, which is also detailed above, ABC Co. instead factors $30mm of payables under a non-recourse arrangement. Since the transfer qualifies as a true sale, the receivables are derecognized from the balance sheet.

Importantly, under this arrangement, total debt remains unchanged, and ABC Co. remains at 3.6x leverage, despite having raised $25mm of immediate cash.

Transactions like this highlight why factoring serves as both a viable funding and financial reporting strategy.

By accelerating the conversion of receivables into cash without recording additional debt, companies can present a stronger liquidity position and lower leverage. However, when factoring is used too aggressively, it can mask excessive underlying leverage or recurring cash shortfalls.

To understand why companies use factoring facilities, we’ll return to ABC Co., covering two primary use cases.

The first and more intuitive use case is working capital management. Imagine that ABC Co. is a middle-market supplier of specialty cleaning products, selling primarily into big box retail, with Walmart accounting for more than 50% of its sales. Like most large retailers, Walmart is able to leverage its scale and bargaining power to negotiate extended payment terms, often 9060+ days, leaving smaller vendors like ABC Co. waiting for months to collect cash.

On the other hand, ABC Co. must pay its own suppliers within 30 days and cover payroll every two weeks. The result is cash flowing out faster than it comes in. By factoring its receivables, ABC Co. is able to accelerate cash receipts from its invoices upfront to cover current working capital needs.

Why doesn’t ABC Co. just borrow on a revolving line of credit?

For companies like ABC Co., factoring functions as a reasonable alternative or supplement to a revolving credit facility. This is because factoring “piggybacks” on the credit quality of ABC Co.’s buyers, which in this case are large investment-grade retailers, rather than its own. This allows for quicker and easier access to capital.

The second use case relates to a company’s leverage optics. Even when a company has adequate liquidity, the accounting treatment of factoring can make it an appealing tool for managing leverage-related metrics.

The clearest example of this is net debt-to-EBITDA. In a true sale arrangement, cash is received, but there is no corresponding liability recorded, representing a dollar-for-dollar decrease in net leverage and no change in total leverage.

This creates a rare and interesting dynamic where a company can raise liquidity while simultaneously lowering reported net leverage, as the cash inflow from factoring is essentially treated as a cash flow from operations rather than financing.

On the other hand, if the company were to borrow via an RCF, cash would increase, but so would debt, leaving net debt the same and increasing total debt.

To illustrate this dynamic, imagine ABC Co. now has a balance sheet with $150mm of outstanding receivables and a covenant limiting total debt to EBITDA of 4x. The company is facing a short-term working capital squeeze following a seasonal inventory build and delayed collections from its Walmart. To fund operations, management considers two options: drawing $30mm on its revolving credit facility or factoring $30mm of receivables under a non-recourse true-sale arrangement. ABC Co.’s pre-transaction balance sheet is presented below:

With $290mm of total debt, representing 3.6x EBITDA, ABC Co. sits just below its 4.0x maximum covenant threshold. With only $20mm of cash on hand, the company expects a temporary working-capital shortfall, as payments come due before collections from its major retail customers.

Under the first option, which is detailed above, ABC Co. draws $30mm from its revolver to fund payables. While this immediately increases cash, it also raises total debt to $320mm, pushing leverage to its maximum limit of 4.0x. Any additional borrowing or decline in EBITDA would push leverage above its limit. While an RCF draw solves ABC Co.’s liquidity problem, it presents the new issue of lender scrutiny.

Under the second option, which is also detailed above, ABC Co. instead factors $30mm of payables under a non-recourse arrangement. Since the transfer qualifies as a true sale, the receivables are derecognized from the balance sheet.

Importantly, under this arrangement, total debt remains unchanged, and ABC Co. remains at 3.6x leverage, despite having raised $25mm of immediate cash.

Transactions like this highlight why factoring serves as both a viable funding and financial reporting strategy.

By accelerating the conversion of receivables into cash without recording additional debt, companies can present a stronger liquidity position and lower leverage. However, when factoring is used too aggressively, it can mask excessive underlying leverage or recurring cash shortfalls.

5) The infamous Weil email explained

We have all seen the below image, but what do it mean?

In an October 2 exchange between Weil and Orrick, Weil acknowledged that they did not know whether First Brands had ever actually received the roughly $1.9bn in factoring proceeds.

Additionally, they confirmed that the segregated collection accounts contained “$0”.

To understand why this is a red flag, you must know that in a properly structured factoring program, cash management and segregation are extremely important.

Under normal circumstances, cash should flow into segregated collection accounts.

Having $0 in a segregated account presents two possibilities: the factoring proceeds were never actually funded, or the proceeds were funded but were immediately commingled along with customer payments.

I believe the latter scenario is more likely, as First Brands burned significant cash prior to filing, which must have come from some source.

This is also consistent with the other widespread breakdown of control, making the factoring proceeds and customer collections indistinguishable from other liquidity sources.

So why is this a big deal? Besides, of course, that the money is gone.

This admission reinforces the breakdown of cash management controls at First Brands, further weakening the true sale argument. If cash wasn’t properly isolated and upstreamed to the factor, First Brands' factoring facility would violate both the legal isolation and effective control principles.

The most interesting point of this case to watch for is the findings of the investigative committee. The facts they uncover, whether double-factoring, comingling, or cash-flow control, could have a material influence on how First Brands’ factored receivables are treated, influencing creditor recoveries.

In short, First Brands has become a live test for the true sale doctrine.

I will dive into this in a lot more details in an upcoming Pari Passu Newsletter edition.

We have all seen the below image, but what do it mean?

In an October 2 exchange between Weil and Orrick, Weil acknowledged that they did not know whether First Brands had ever actually received the roughly $1.9bn in factoring proceeds.

Additionally, they confirmed that the segregated collection accounts contained “$0”.

To understand why this is a red flag, you must know that in a properly structured factoring program, cash management and segregation are extremely important.

Under normal circumstances, cash should flow into segregated collection accounts.

Having $0 in a segregated account presents two possibilities: the factoring proceeds were never actually funded, or the proceeds were funded but were immediately commingled along with customer payments.

I believe the latter scenario is more likely, as First Brands burned significant cash prior to filing, which must have come from some source.

This is also consistent with the other widespread breakdown of control, making the factoring proceeds and customer collections indistinguishable from other liquidity sources.

So why is this a big deal? Besides, of course, that the money is gone.

This admission reinforces the breakdown of cash management controls at First Brands, further weakening the true sale argument. If cash wasn’t properly isolated and upstreamed to the factor, First Brands' factoring facility would violate both the legal isolation and effective control principles.

The most interesting point of this case to watch for is the findings of the investigative committee. The facts they uncover, whether double-factoring, comingling, or cash-flow control, could have a material influence on how First Brands’ factored receivables are treated, influencing creditor recoveries.

In short, First Brands has become a live test for the true sale doctrine.

I will dive into this in a lot more details in an upcoming Pari Passu Newsletter edition.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh