Today, ~80% of India's organised tea estates fell into cash losses, and premium Assam teas have crashed 27%. But one question looms large—how is a country that swears by chai hurting so badly in tea production?

Let's find out. 🧵👇

Let's find out. 🧵👇

Hemant Bangur, chairman of the Indian Tea Association, warned that "only a handful of estates will achieve positive EBITDA, thus eroding the industry's financial foundations further." Tea prices have crashed from ₹304/kg to ₹221/kg. The ITA is calling for a minimum support price.

This isn't just about oversupply. Supply shocks are squeezing revenues while demand-side shocks are increasing costs—a double whammy for profitability in the world's second-largest tea producing country. And this has been happening for the last few years.

The most significant supply shock is climate change. Tea has thrived on predictable weather—summer heat that isn't piping hot, and consistent rains distributed evenly over time. But climate volatility has thrown a wrench into the entire supply chain.

This year, rains in Assam—India's leading tea state—fell 38% below the monsoon average. This crunched the harvest during May-June, generally considered the best season. When rain comes suddenly, the resulting crop floods the market all at once.

This volatility has introduced severe price swings. In 2024, a drought-induced output drop drove prices up by ~18%. However, as production rebounded suddenly this year, prices crashed by at least ₹30 per kilogram in many cities.

Erratic weather is also destroying quality. When temperatures spike or rains fail during critical growth periods, stressed bushes produce inferior leaves. Pest and fungal attacks have surged with weather extremes—planters report leaves riddled with holes and discolored.

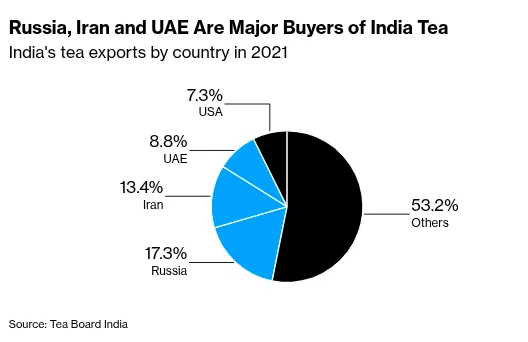

The second supply shock is related to exports. India typically exports 16-18% of its tea—a whopping ~258 million kg in FY25. But various kinds of geopolitical risks are showing up unattended to India's tea party.

Take Iran, our second-largest tea buyer. The Iran-Israel conflict forced shipments to halt, with consignments stranded midway. Indian exporters are now unwilling to sell to Iran as they're unsure of receiving payments. Buyers in the Middle East are pulling back too.

US sanctions on both Iran and Russia—India's largest tea buyer—make exports even more unpredictable. And there's a 25% US tariff on Indian tea from the Trump era. In 2023, India's tea exports fell 1.4%, with average prices down 3.5%.

But there's another dimension: a global tea glut. Both Kenya and Sri Lanka have reported strong output this year while producing at lower costs than us. But like us, they're also unable to find international buyers. So they're dumping excess output in India.

Kenyan tea is priced at ~₹155/kg, far cheaper than Indian auction prices of ₹250/kg. With a 288% jump in imports, India has become Kenya's largest importer. Some blenders use it to reduce costs, or even re-export it as "Indian" tea, undermining both prices and quality reputation.

The third supply shock is structural: small tea growers (STGs) now dominate the industry—making up 54% of production. This is a vast change from just a decade ago, when their share was just 36%.

The change wasn't entirely unpredictable. Earlier, tea required strict permissions from the Tea Board. Large estates could bear certification costs, but not small farmers. However, deregulation fully suspended all permissions in 2021, allowing marginal farmers to grow tea freely.

This was a double-edged sword. While it dramatically expanded production, it brought in many unorganized, unregistered players. STGs don't face high labor costs or regulations like larger estates. They produce tea at ₹50-70 per kg less cost and can profit where big estates lose money.

Quality is also a problem. Small growers aren't subject to quality checks or pesticide controls like large players. Their inferior leaves get mixed with higher-quality estate tea, spoiling the total pool.

As a result, auctions are drowning. In Kolkata, Guwahati, and Siliguri, prices fell ₹32-74/kg from mid-2025, with 30% of tea going unsold. Kavi Seth, chairman of J. Thomas, India's largest auctioneer, blamed "the mushrooming of small growers in the past two decades."

Now, falling prices would be manageable if costs were stable. They're not. Fertilizer prices have increased. Wages have risen 8-9%. Energy costs are climbing—tea processing requires massive amounts of firewood, coal, or gas. Irrigation costs have surged after climate shocks made rainfall unreliable.

The crisis is affecting companies unevenly. Plantation companies are in survival mode. McLeod Russel's net profit fell 53% in 2023 and had to restructure debt. Goodricke has sold estates in Assam, is converting some into hotels, and diversifying into milk and vegetables.

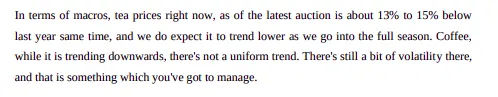

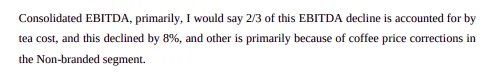

Branded tea companies like Tata Consumer and HUL are in a different position. They buy tea at auction and package it. Tata slashed retail prices 10-15%, achieving double-digit growth, though two-thirds of their 2.5% margin decline came from tea costs.

HUL cut prices 5-15% but held margins steadier at ~22%. Many are calling for urgent intervention—minimum support prices, import controls, subsidies. For chai drinkers, cheaper tea is nice. For estate owners and workers, this is an existential crisis.

We cover this and one more interesting story in today's edition of The Daily Brief. Watch on YouTube, read on Substack, or listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

All links here: thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/is-there-a-p…

All links here: thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/is-there-a-p…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh