Last quarter, Blinkit’s management spoke about what they called a structural shift in their business: moving from a marketplace model to an inventory-led model, where Blinkit owns what it sells.

CFO Akshant Goyal had said:

“most of our business will move to inventory ownership and margin accretion should also happen in that timeframe.”

CFO Akshant Goyal had said:

“most of our business will move to inventory ownership and margin accretion should also happen in that timeframe.”

Owning stock changes the unit economics. You don’t just earn a commission, you earn the full spread between buying price and selling price.

Think about it: if Blinkit buys Maggi, say, for all its operations across India, how much cheaper could it get it?

Meanwhile, they also maintain product quality, reduce stock-outs, and maybe even improve overall customer experience. That can add up to more profits and a stronger moat.

Think about it: if Blinkit buys Maggi, say, for all its operations across India, how much cheaper could it get it?

Meanwhile, they also maintain product quality, reduce stock-outs, and maybe even improve overall customer experience. That can add up to more profits and a stronger moat.

But the moment you start owning stock, you also start holding cash in that stock. Every unit sitting in a warehouse is money paid out, not yet earned back. That’s working capital.

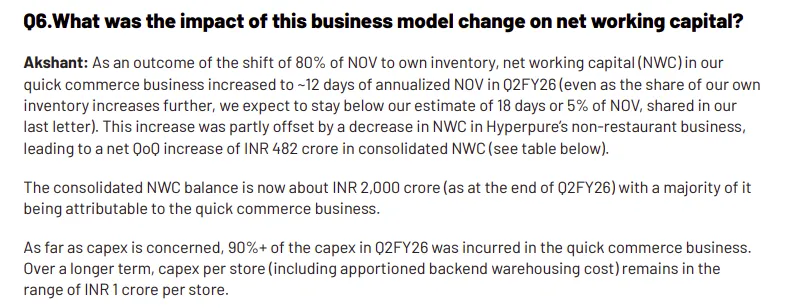

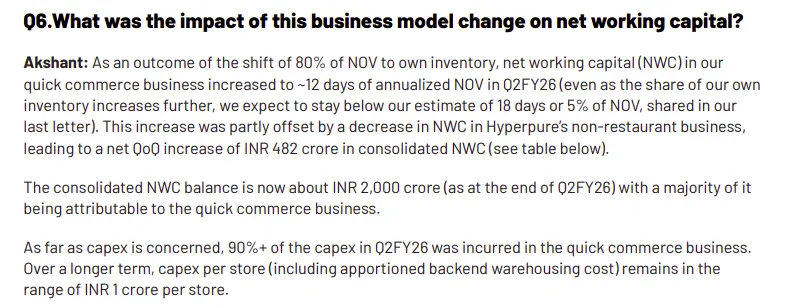

Back in Q1, the CFO had said this would increase. At full scale, they expected roughly eighteen days of working capital, or about five percent of net order value.

Back in Q1, the CFO had said this would increase. At full scale, they expected roughly eighteen days of working capital, or about five percent of net order value.

But Blinkit also argued it isn’t like a supermarket.

On the concall, when an analyst compared Blinkit to DMart, Albinder explained why that comparison doesn’t really hold. A retailer like DMart carries big, slow-moving categories that can sit for weeks. Blinkit’s mix turns much faster.

Groceries and daily-use items come in and go out several times a week. Because of that speed, the inventory Blinkit needs to keep at any moment is far smaller—even though working capital still rises versus a pure marketplace.

On the concall, when an analyst compared Blinkit to DMart, Albinder explained why that comparison doesn’t really hold. A retailer like DMart carries big, slow-moving categories that can sit for weeks. Blinkit’s mix turns much faster.

Groceries and daily-use items come in and go out several times a week. Because of that speed, the inventory Blinkit needs to keep at any moment is far smaller—even though working capital still rises versus a pure marketplace.

This quarter, the shift shows up in the numbers. ~80% of sales now come from Blinkit’s own inventory.

Working capital has started to build—about twelve days of sales worth of stock, roughly ₹2,000 crore of cash inside the system, most of it in quick-commerce.

That’s the cost of control.

New categories or new warehouses mean more cash locked into goods that haven’t sold yet. Earlier, that inventory sat on someone else’s balance sheet. Now it sits on Blinkit’s.

Working capital has started to build—about twelve days of sales worth of stock, roughly ₹2,000 crore of cash inside the system, most of it in quick-commerce.

That’s the cost of control.

New categories or new warehouses mean more cash locked into goods that haven’t sold yet. Earlier, that inventory sat on someone else’s balance sheet. Now it sits on Blinkit’s.

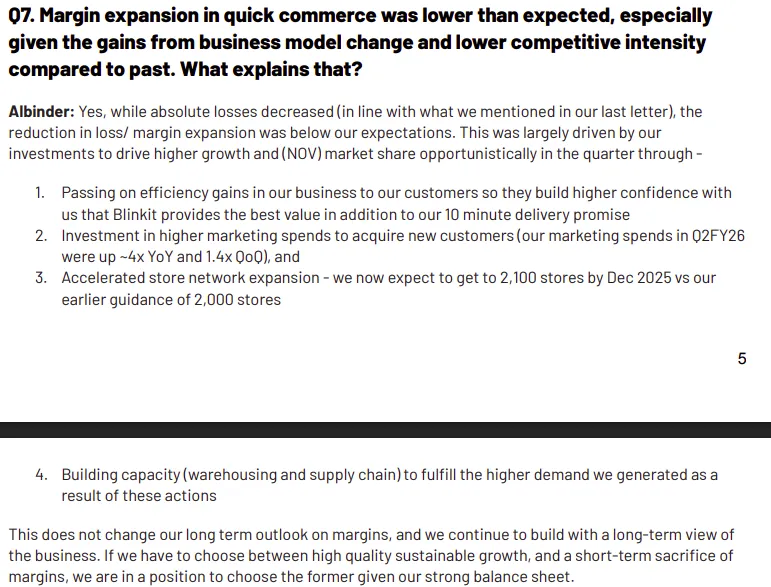

And while this change was meant to help margins, the improvement hasn’t shown up yet. The shareholder letter says:

“while absolute losses decreased, the reduction in loss or margin expansion was below expectations.”

Translation: they expected faster margin expansion but chose aggression. Marketing spends were ~4x YoY. They opened more stores, built capacity, and pushed share. The efficiency headroom from owning inventory is being reinvested to grow.

“while absolute losses decreased, the reduction in loss or margin expansion was below expectations.”

Translation: they expected faster margin expansion but chose aggression. Marketing spends were ~4x YoY. They opened more stores, built capacity, and pushed share. The efficiency headroom from owning inventory is being reinvested to grow.

In theory, controlling what you buy, how you price, and how quickly you turn stock should make each order slightly more profitable over time. In practice, the near-term picture stays flat because those gains are being used to fund expansion.

This is how transitions look up close: the accounting hits first—cash goes out when you start buying inventory. The benefits i.e. steadier supply, better prices, happier customers, compound more slowly.

This is how transitions look up close: the accounting hits first—cash goes out when you start buying inventory. The benefits i.e. steadier supply, better prices, happier customers, compound more slowly.

For a while, the business looks heavier before it looks more profitable. As Albinder says:

“If we have to choose between high quality sustainable growth, and a short-term sacrifice of margins, we are in a position to choose the former given our strong balance sheet.”

“If we have to choose between high quality sustainable growth, and a short-term sacrifice of margins, we are in a position to choose the former given our strong balance sheet.”

We cover this and one more interesting story in today's edition of Who said what? Watch on YouTube or read on Substack. All links here:

thedailybriefing.substack.com/p/blinkit-is-c…

thedailybriefing.substack.com/p/blinkit-is-c…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh