Boobtech is amazing.

It's an area that the rest of medicine could look to as an example.

The professionals making bigger, more realistic breast implants are simultaneously improving affordability, safety, and quality at a rapid rate🧵

It's an area that the rest of medicine could look to as an example.

The professionals making bigger, more realistic breast implants are simultaneously improving affordability, safety, and quality at a rapid rate🧵

Consider one of the most recent improvements in boobtech: the Mia.

The Mia is the first successful "injectable" breast implant.

It cuts down scarring, complications, surgery time and cost, and it looks and feels more realistic than earlier implants.

The Mia is the first successful "injectable" breast implant.

It cuts down scarring, complications, surgery time and cost, and it looks and feels more realistic than earlier implants.

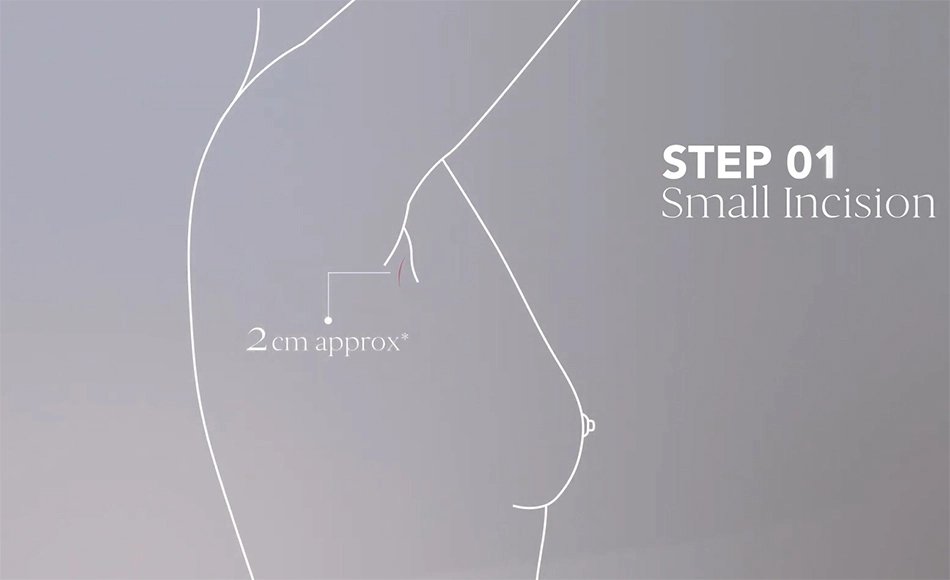

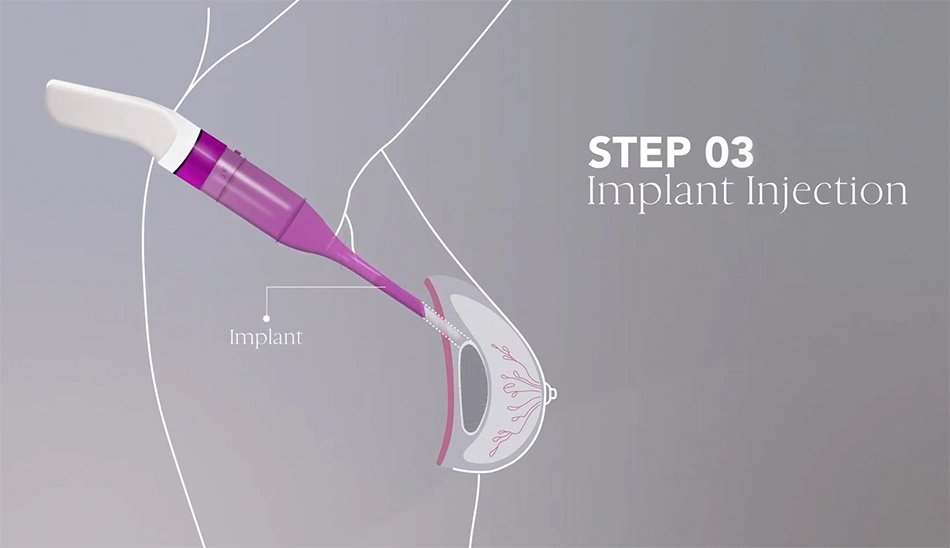

The Mia is installed with a small armpit incision about 2 centimeters in length.

This is a significant reduction from earlier generations, which were regularly closer to 7 centimeters, or almost 3 inches.

This is a significant reduction from earlier generations, which were regularly closer to 7 centimeters, or almost 3 inches.

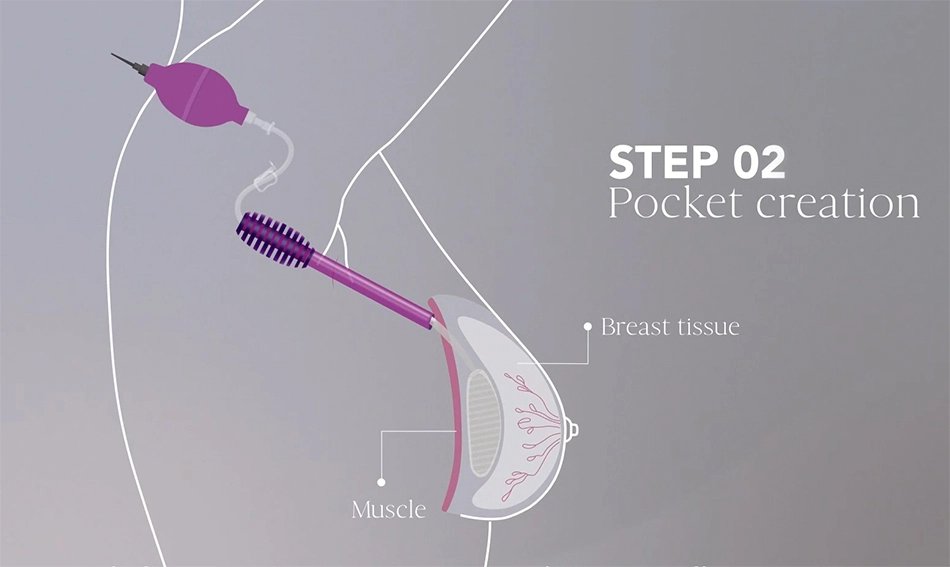

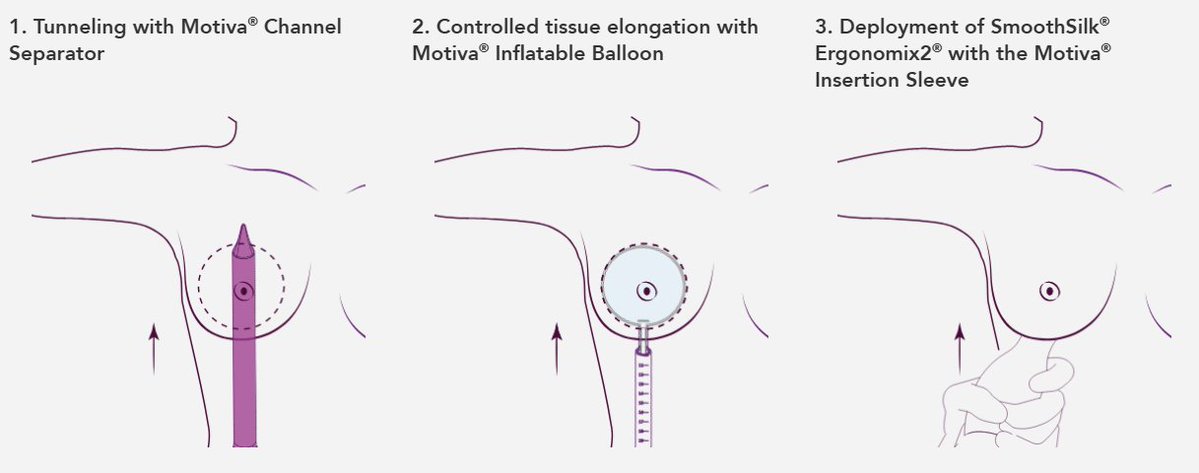

After incision, a pocket is created with a custom balloon tool designed by the creators of the Mia, Establishment Labs

This approach is done without having to put the woman under. Only local anesthetic used, which reduces surgical complication rates, exposure to anesthesia, etc.

This approach is done without having to put the woman under. Only local anesthetic used, which reduces surgical complication rates, exposure to anesthesia, etc.

Finally, with another custom tool, the implant is inserted into the pocket, pulled up, and done.

The total procedure time is 15 minutes. The total time in office averages about 90 minutes, including doctor preparation, patient briefing, and so on.

The total procedure time is 15 minutes. The total time in office averages about 90 minutes, including doctor preparation, patient briefing, and so on.

And you're done!

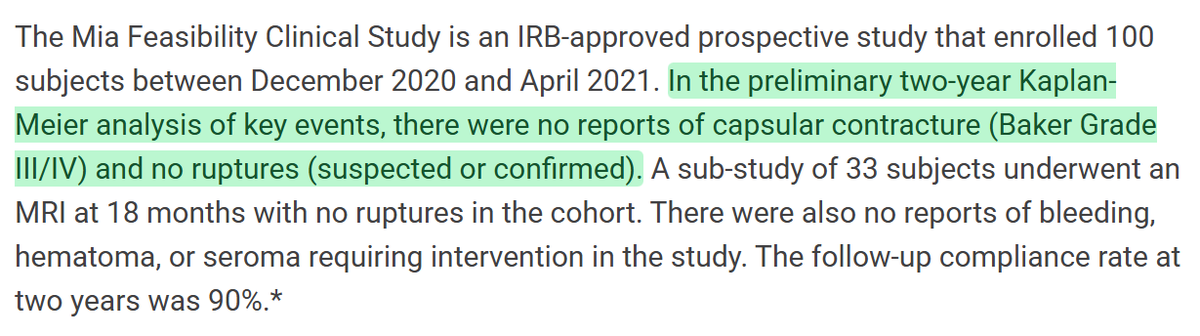

You can go back to your daily activities next day. There's a minimal recovery, and there's minimal follow-on side effects

In fact, though traditional breast implants lead to somewhere between 6-13% rupture rates and 15% contracture, the Mia's first trial saw 0!

You can go back to your daily activities next day. There's a minimal recovery, and there's minimal follow-on side effects

In fact, though traditional breast implants lead to somewhere between 6-13% rupture rates and 15% contracture, the Mia's first trial saw 0!

The Mia includes an optional non-ferromagnetic RFID sensor that can hold patient device info for peace of mind.

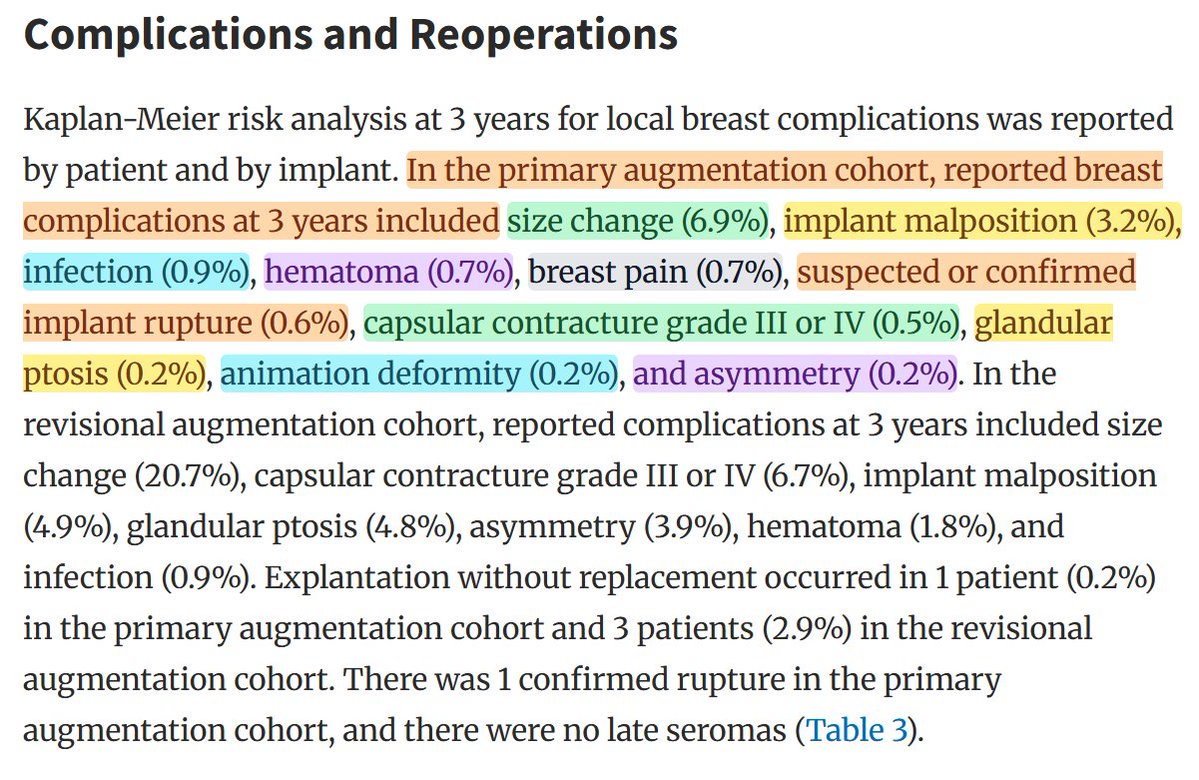

The Mia isn't even the best out there!

Preservé preserves more breast tissue and the implant it's paired with gives women a fuller upper-breast (frequently desired).

The Mia isn't even the best out there!

Preservé preserves more breast tissue and the implant it's paired with gives women a fuller upper-breast (frequently desired).

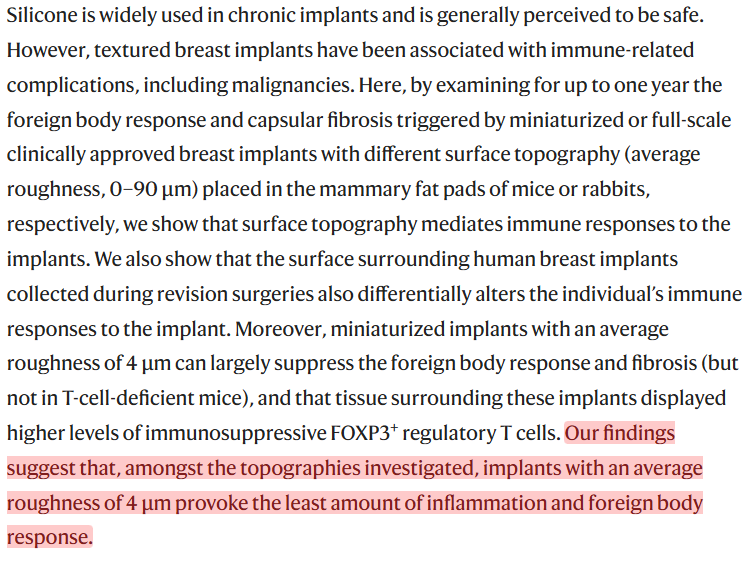

The implant it's used with delivers fractions of the typical complication rate, for a much gentler surgery, with a much more realistic feeling, greater patient comfort, an easy recovery, and so on.

It is an amazing advance in boobtech.

It is an amazing advance in boobtech.

The biomaterial it's made from also minimizes immune reactions to implantation.

This was a feat of biomedical engineering generated by exploring material options and winding up with something that really just works!

This was a feat of biomedical engineering generated by exploring material options and winding up with something that really just works!

And there are already other boobtech improvements in the pipeline! I could go on, but won't.

I want to talk about why boobtech is so advanced.

I think it has to do with three things.

The first is the much lower regulatory burdens compared to trad pharma.

I want to talk about why boobtech is so advanced.

I think it has to do with three things.

The first is the much lower regulatory burdens compared to trad pharma.

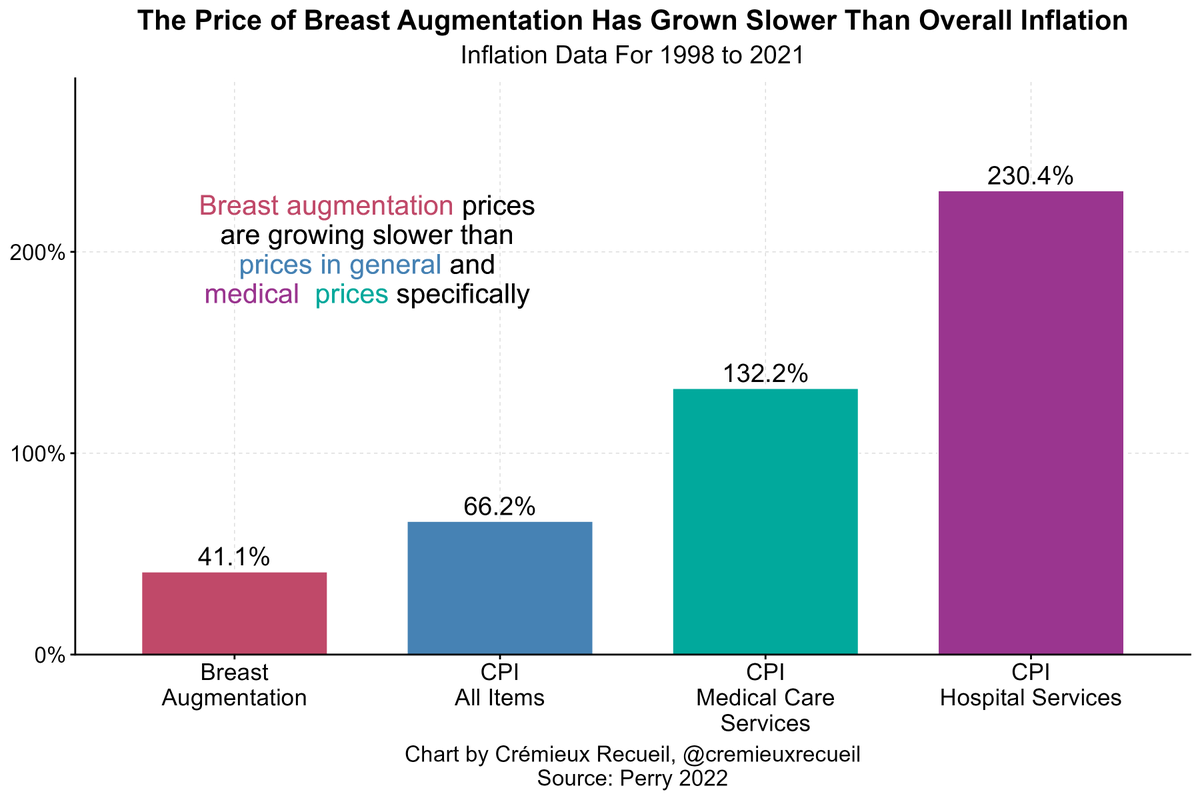

Low regulatory burden benefits make sense, so I'll explain the second thing:

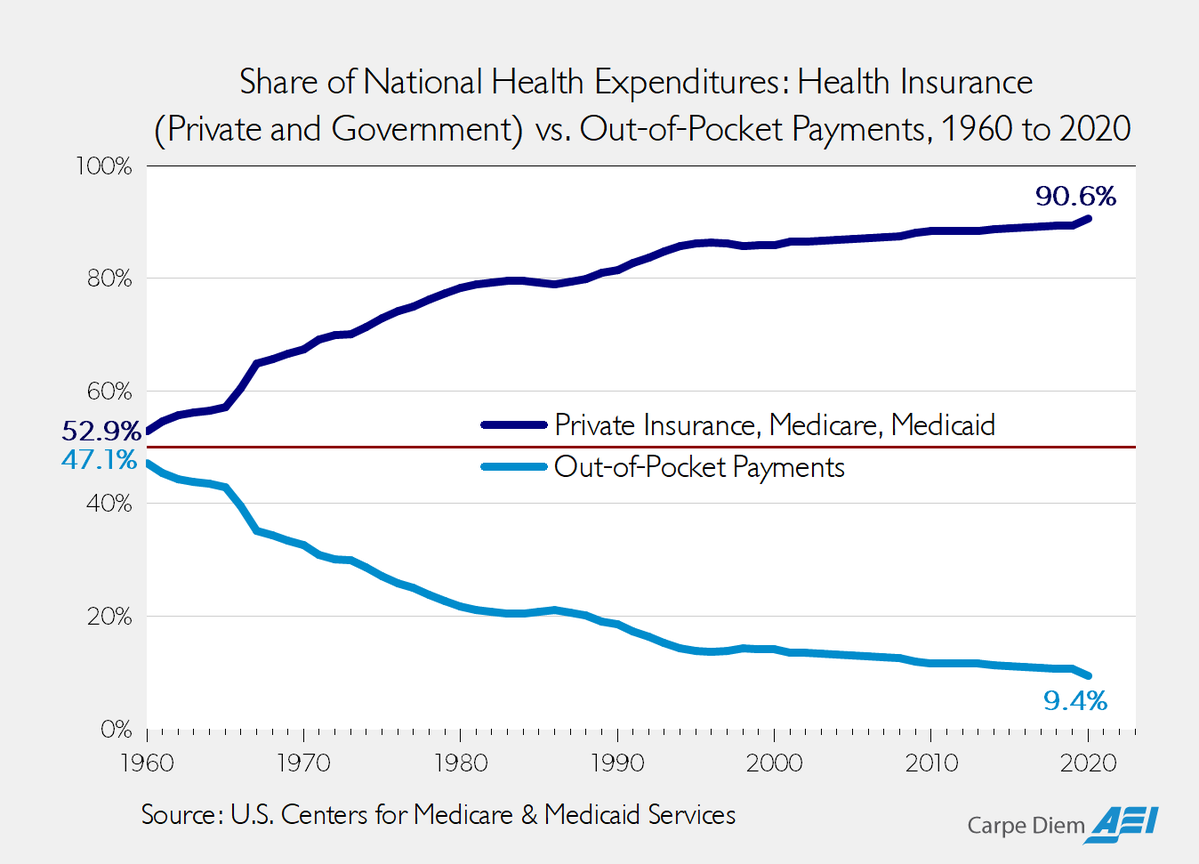

A higher out-of-pocket share.

Plastic surgery is often not covered by insurers. It's aesthetic, optional, etc. Patients cannot tolerate massive cost inflation if they have to pay it, so they don't!

A higher out-of-pocket share.

Plastic surgery is often not covered by insurers. It's aesthetic, optional, etc. Patients cannot tolerate massive cost inflation if they have to pay it, so they don't!

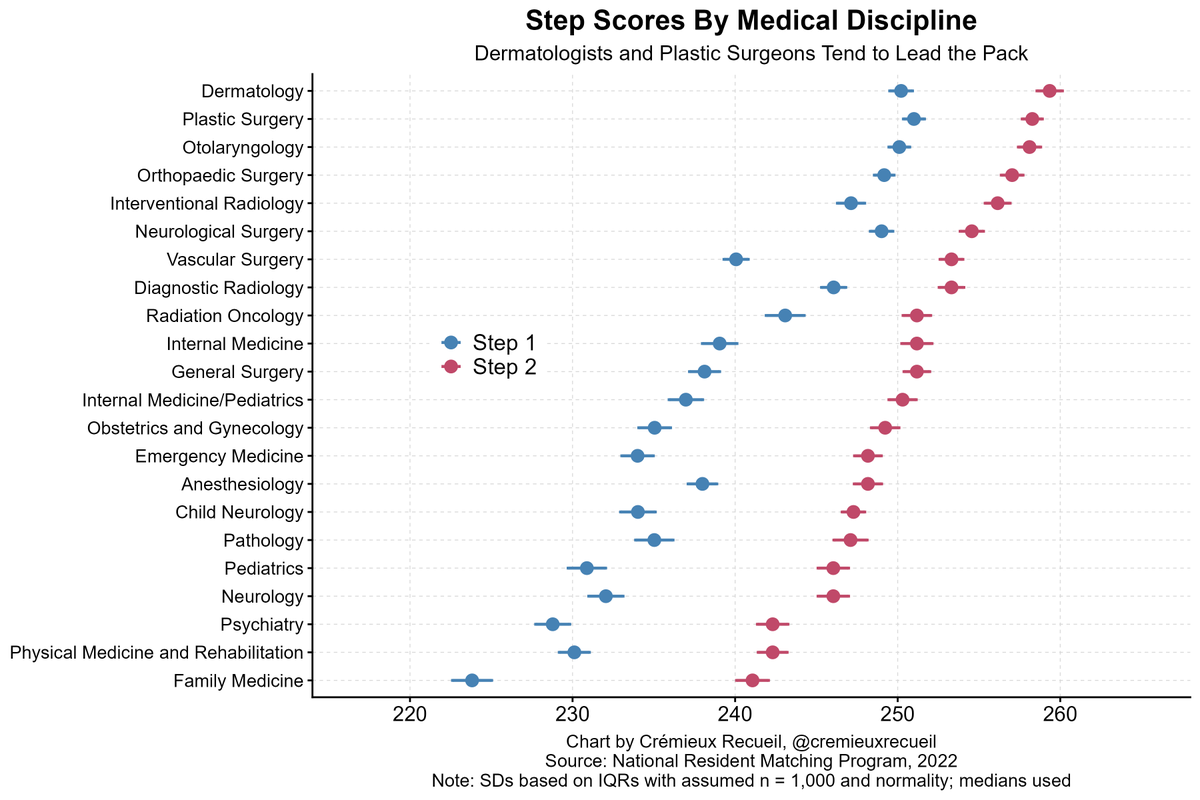

And finally, plastic surgery attracts some of the smartest doctors

The smartest doctors in a given year tend to be either dermatologists or plastic surgeons, because those disciplines tend to offer more work-life balance

They're not high-pressure, but they still reward highly

The smartest doctors in a given year tend to be either dermatologists or plastic surgeons, because those disciplines tend to offer more work-life balance

They're not high-pressure, but they still reward highly

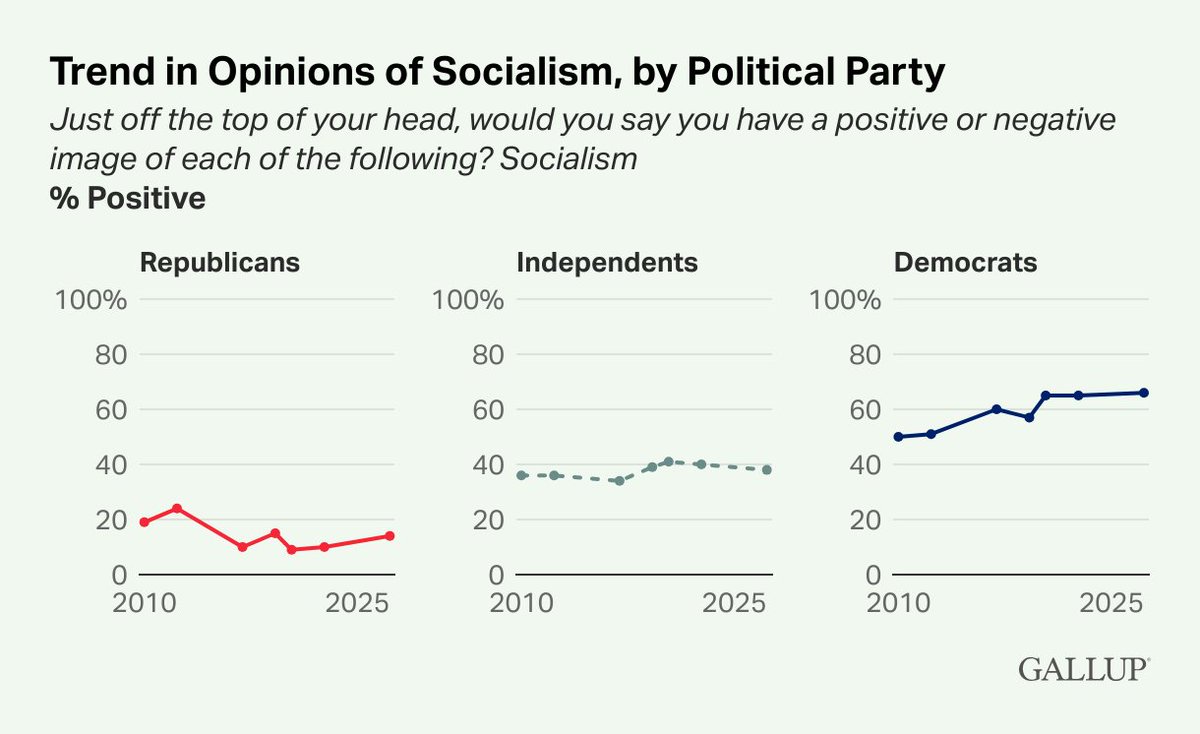

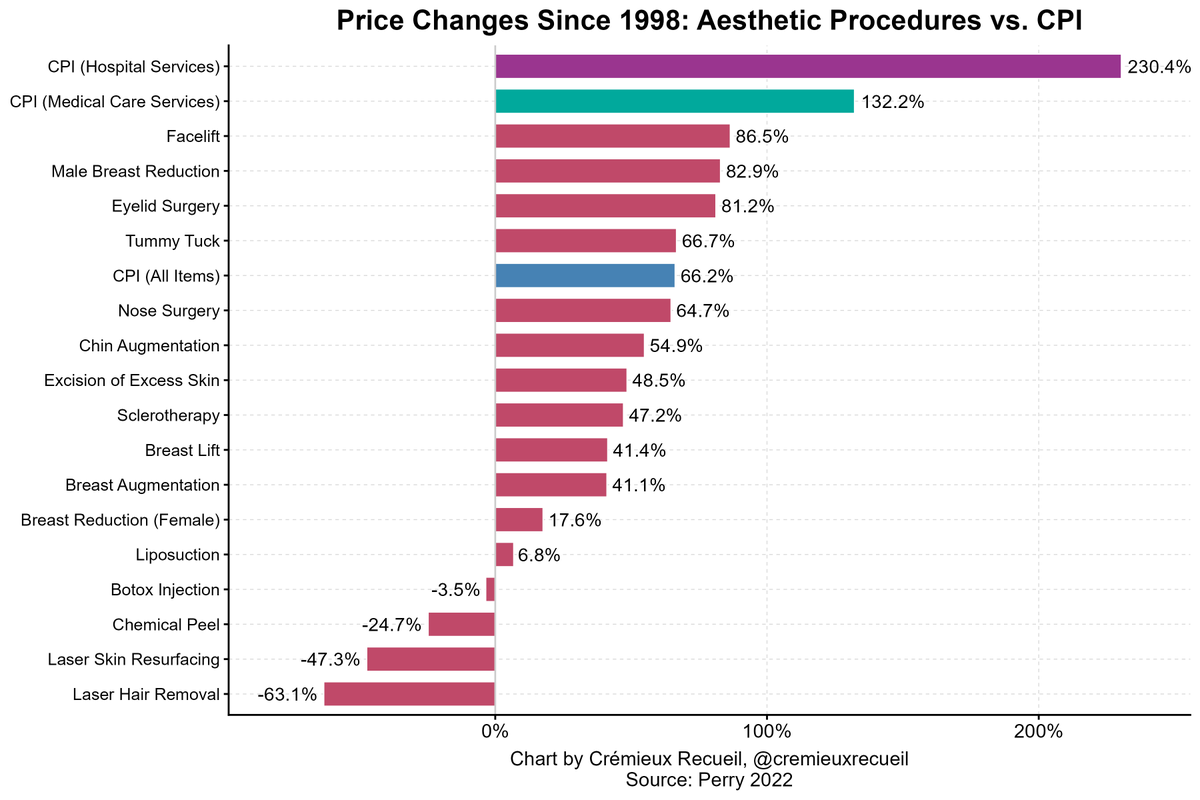

In fact, I think these tie into why aesthetic procedures are generally high-performing when it comes to price, innovations, etc.

Just look at how they compare to inflation in general and inflation in medicine more broadly.

They're great!

Just look at how they compare to inflation in general and inflation in medicine more broadly.

They're great!

Aesthetic procedures are a model for how medicine ought to work

Not entirely, but at least partly

There should be room for new tech paid for by patients; room for docs to train with tech and implement rapidly all the time

There should be more room for progress and big breasts!

Not entirely, but at least partly

There should be room for new tech paid for by patients; room for docs to train with tech and implement rapidly all the time

There should be more room for progress and big breasts!

Anyway, just my two cents.

The pace of progress in boobtech is incredible. I want that for every area of medicine.

Sources:

aei.org/carpe-diem/wha…

emreozenalp.com/mia-femtech/

establishmentlabs2023cr.q4web.com/press-releases…

motiva.health/surgeons-prese…

academic.oup.com/asj/article/44…

nature.com/articles/s4155…

The pace of progress in boobtech is incredible. I want that for every area of medicine.

Sources:

aei.org/carpe-diem/wha…

emreozenalp.com/mia-femtech/

establishmentlabs2023cr.q4web.com/press-releases…

motiva.health/surgeons-prese…

academic.oup.com/asj/article/44…

nature.com/articles/s4155…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh