Today’s #manuscriptmonday is all about the King James Bible. Arguably the most well known English translation, a translation fit for a king! (A 🧵)…

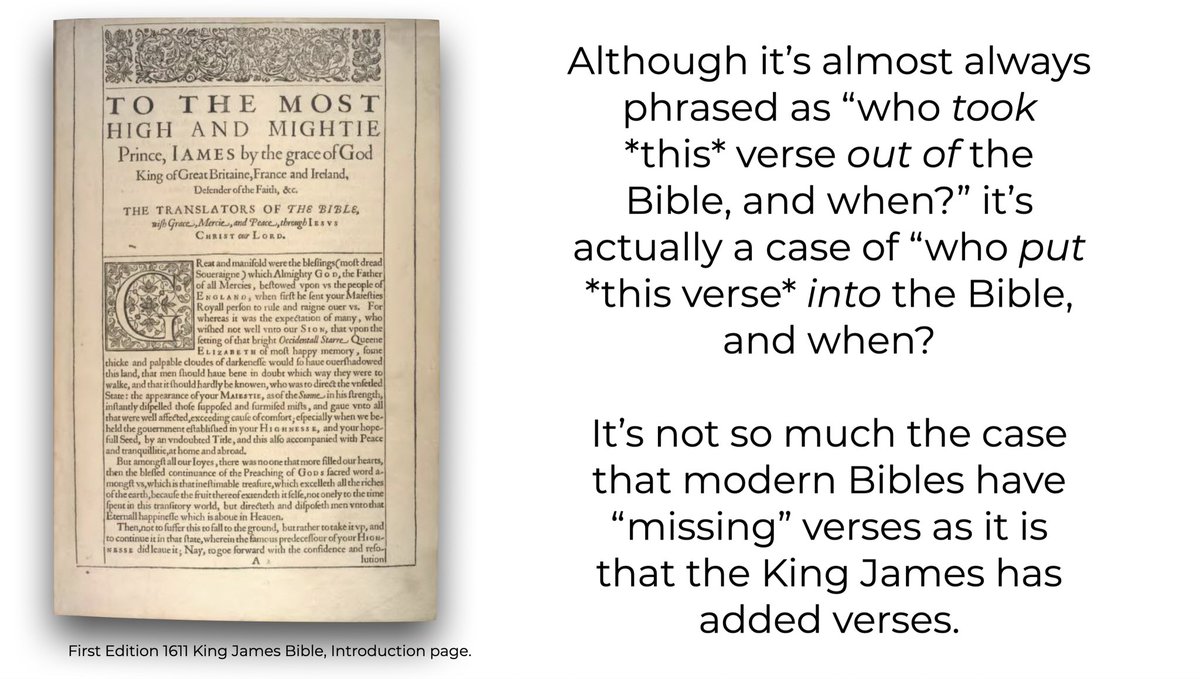

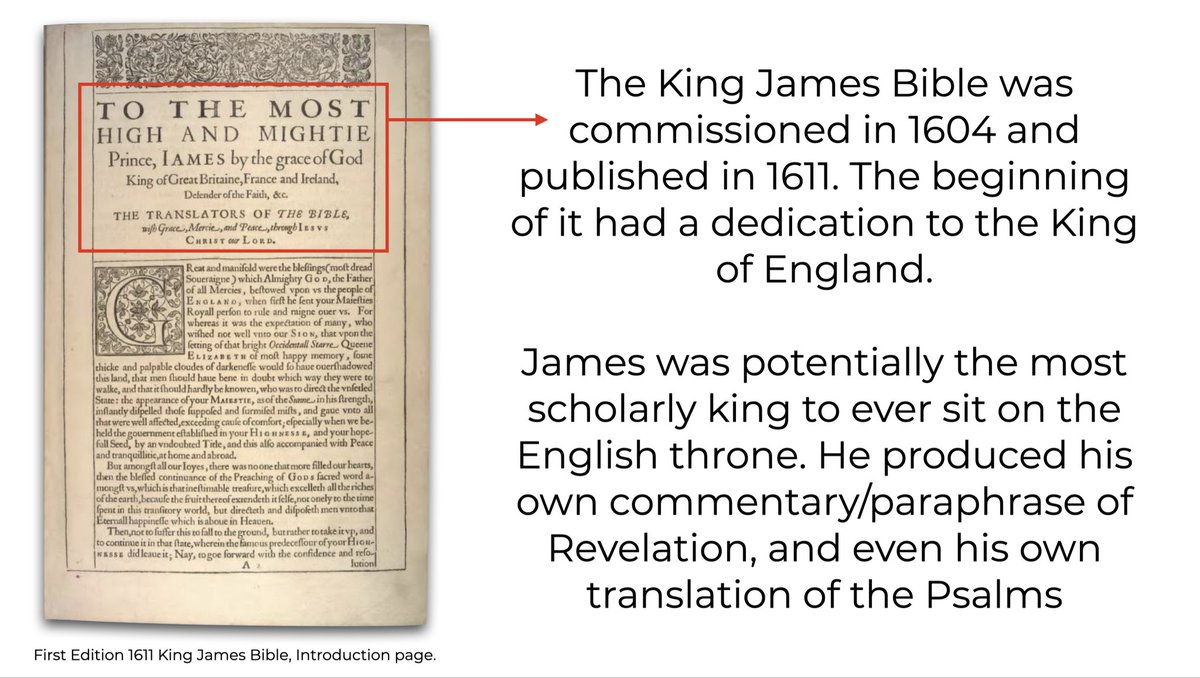

The King James Bible was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611. The beginning of it had a dedication to the King of England.

James was potentially the most scholarly king to ever sit on the English throne. He produced his own commentary/paraphrase of Revelation, and even his own translation of the Psalms.

James was potentially the most scholarly king to ever sit on the English throne. He produced his own commentary/paraphrase of Revelation, and even his own translation of the Psalms.

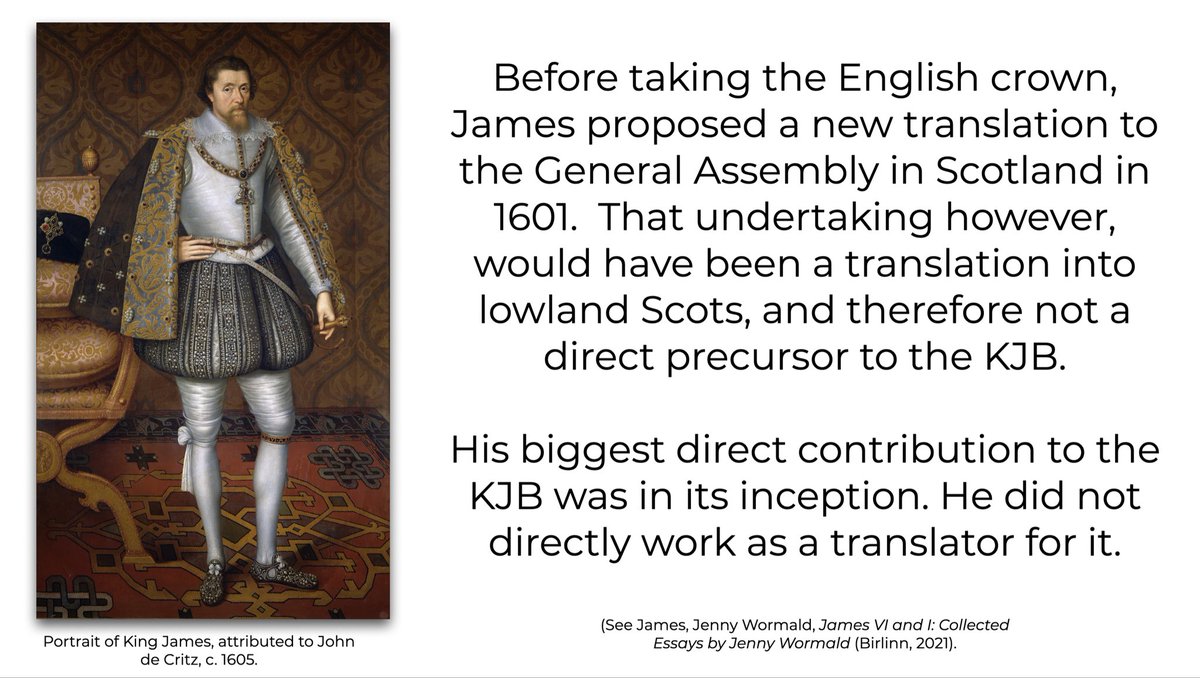

Before taking the English crown, James proposed a new translation to the General Assembly in Scotland in

1601. That undertaking however, would have been a translation into lowland Scots, and therefore not a direct precursor to the KJB.

His biggest direct contribution to the

KJB was in its inception. He did not directly work as a translator for it.

1601. That undertaking however, would have been a translation into lowland Scots, and therefore not a direct precursor to the KJB.

His biggest direct contribution to the

KJB was in its inception. He did not directly work as a translator for it.

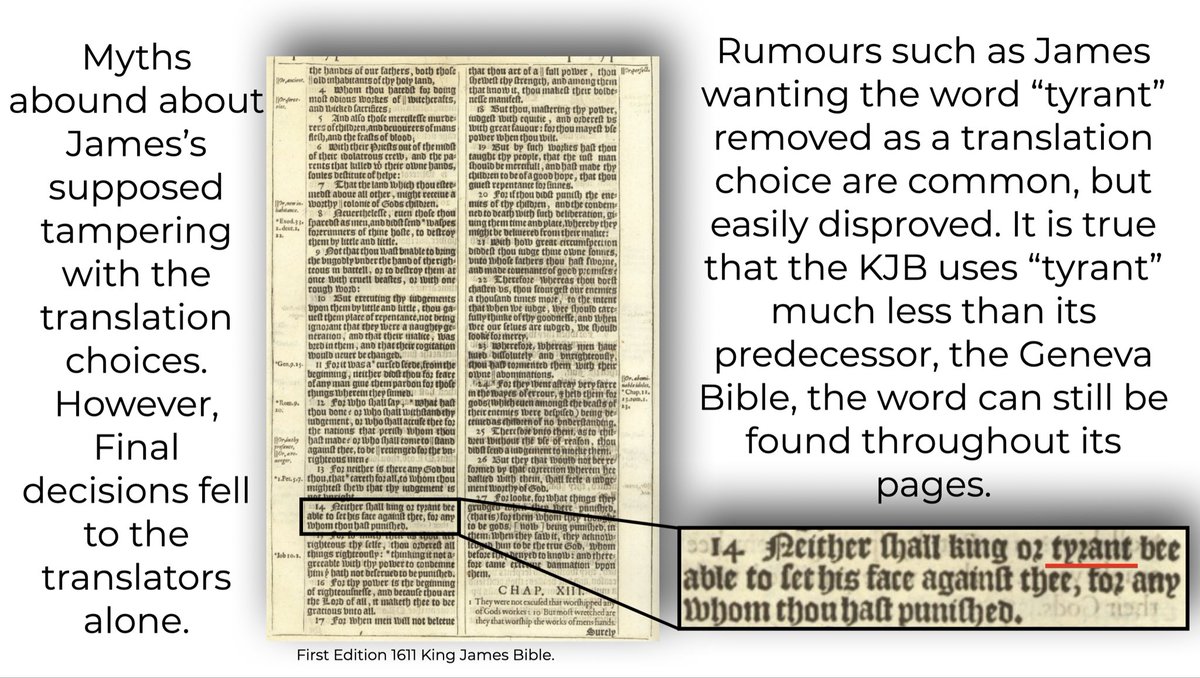

Myths abound about James's supposed tampering with the translation choices. However, Final decisions fell to the translators alone.

Rumours such as James wanting the word "tyrant" removed as a translation choice are common, but easily disproved. It is true that the KJB uses "tyrant" much less than its

predecessor, the Ceneva Bible, the word can still be found throughout its pages.

Rumours such as James wanting the word "tyrant" removed as a translation choice are common, but easily disproved. It is true that the KJB uses "tyrant" much less than its

predecessor, the Ceneva Bible, the word can still be found throughout its pages.

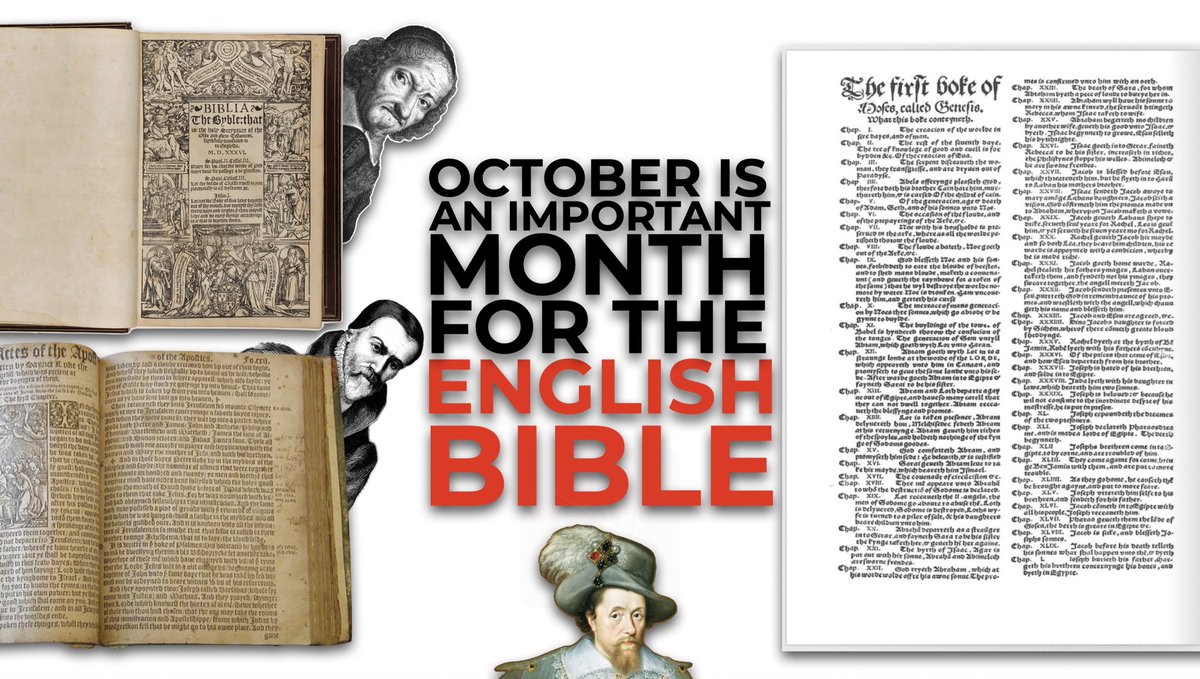

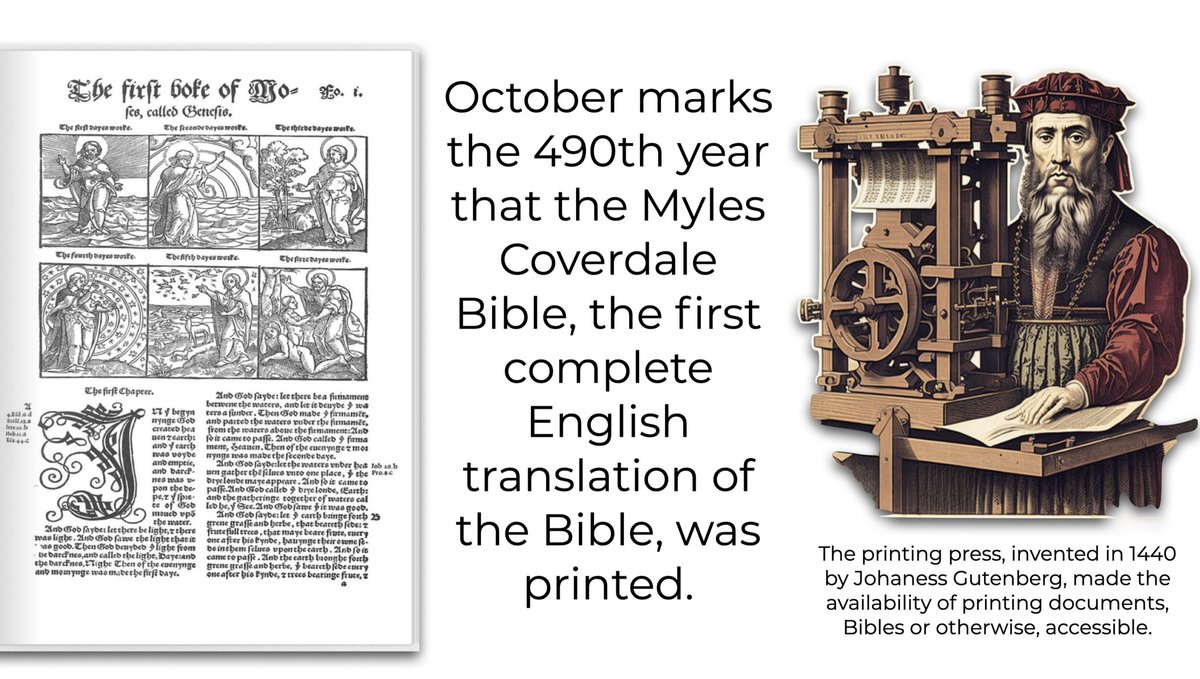

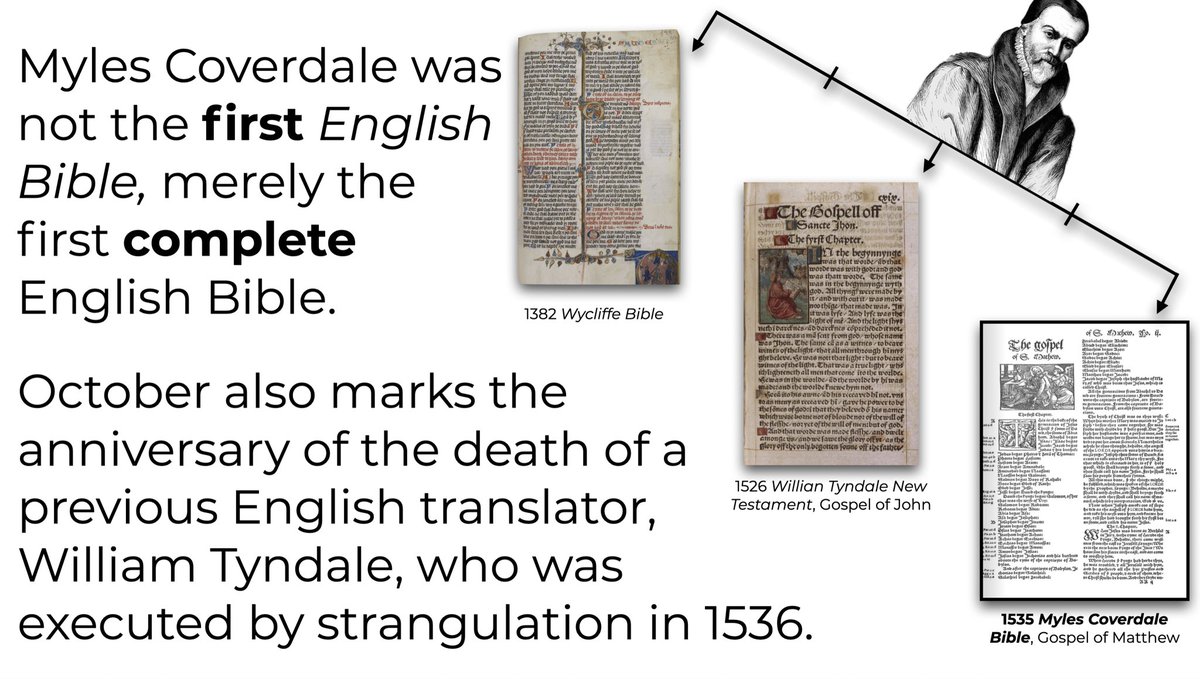

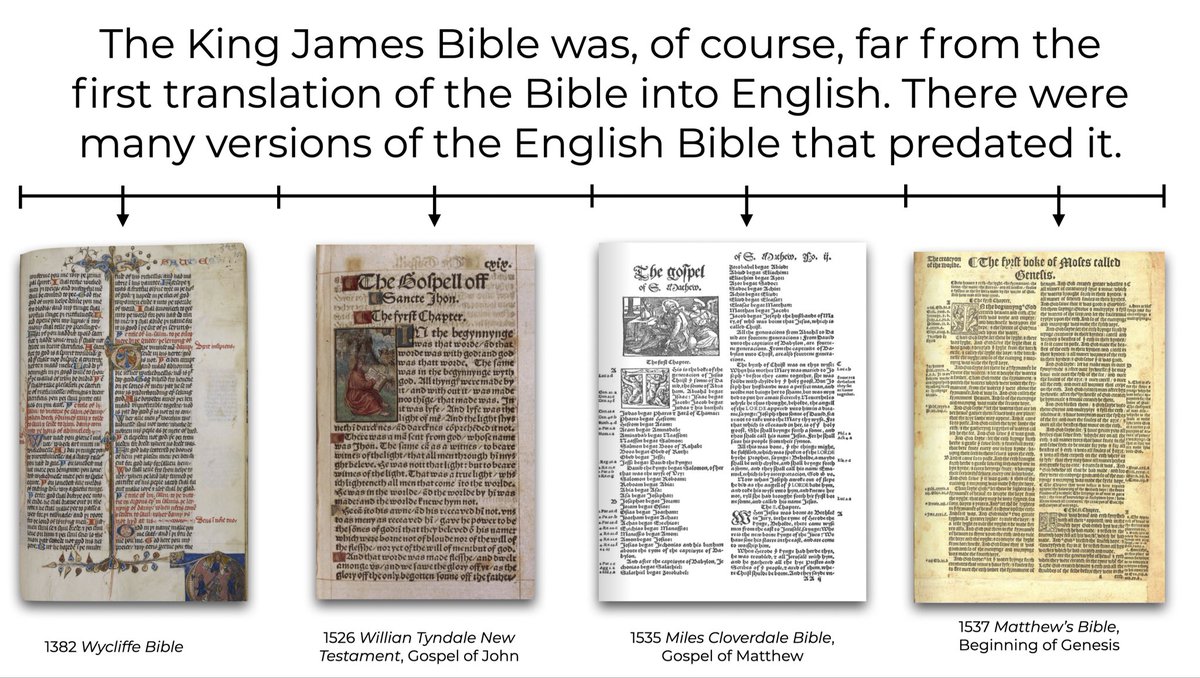

The King James Bible was, of course, far from the first translation of the Bible into English. There were many versions of the English Bible that predated it.

The Venerable Bede produced a translation of the Gospel of John in Old English in the 8th century, although no surviving copies of it survive today. In the 7th century Aldhelm, Bishop of Sherborne and Abbot Malmesbury were reported to have translated the Pslams into Old English.

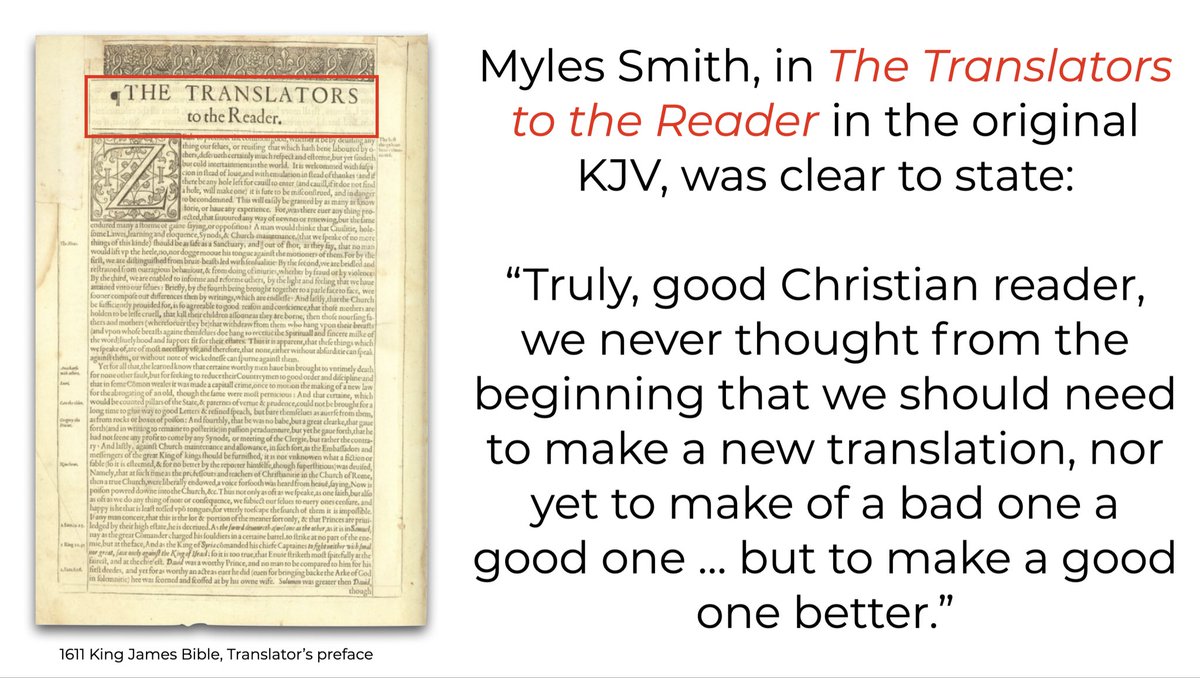

Myles Smith, in The Translators to the Reader in the original

KJV, was clear to state: "Truly, good Christian reader, we never thought from the beginning that we should need to make a new translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one... but to make a good one better."

KJV, was clear to state: "Truly, good Christian reader, we never thought from the beginning that we should need to make a new translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one... but to make a good one better."

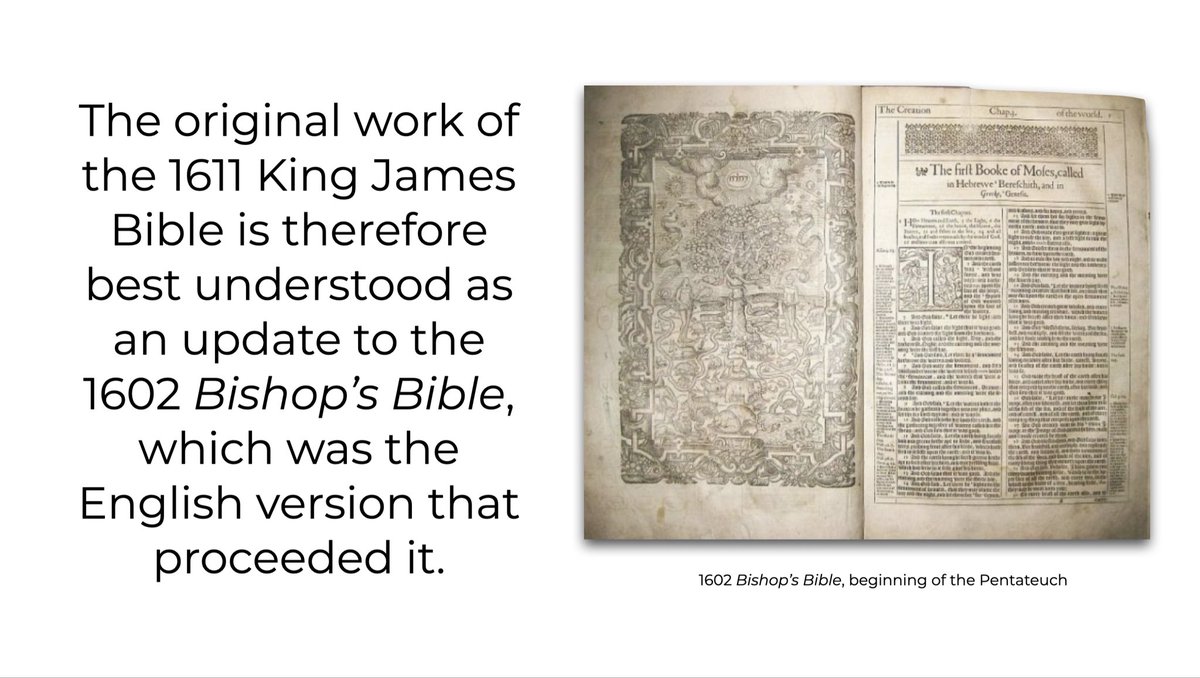

The original work of the 1611 King James Bible is therefore best understood as an update to the

1602 Bishop's Bible, which was the English version that proceeded it.

1602 Bishop's Bible, which was the English version that proceeded it.

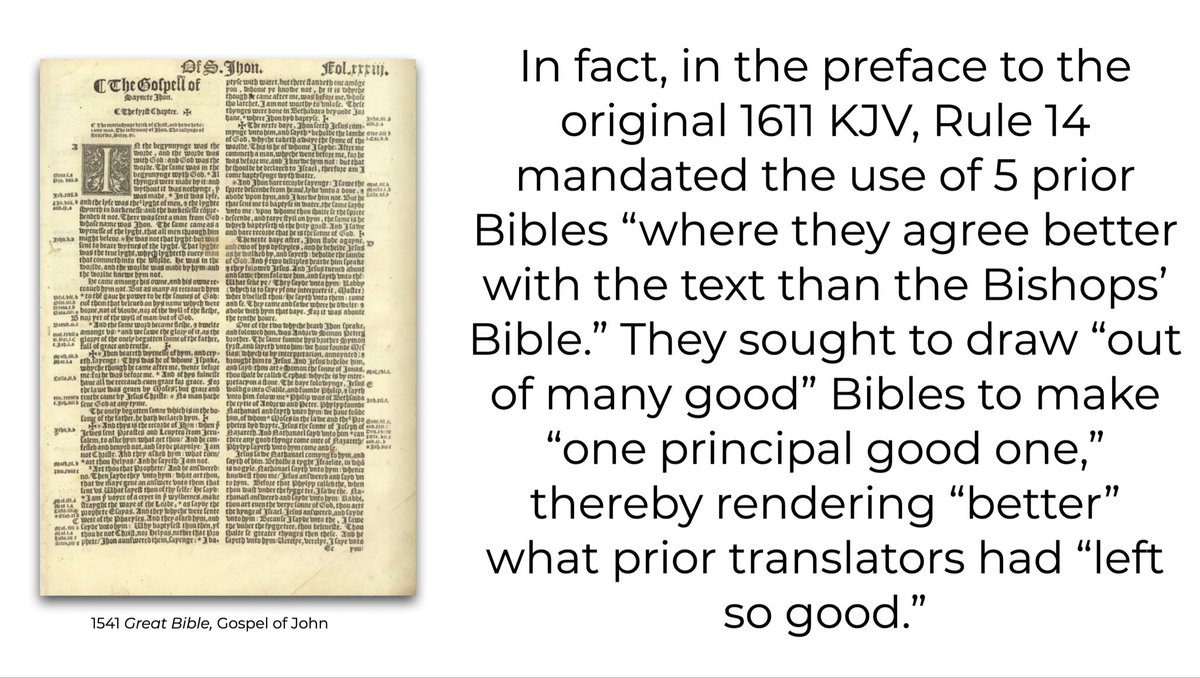

In fact, in the preface to the original 1611 KJV, Rule 14 mandated the use of 5 prior Bibles "where they agree better with the text than the Bishops' Bible." They sought to draw "out of many good" Bibles to make

"one principal good one,' thereby rendering "better" what prior translators had "left so good."

"one principal good one,' thereby rendering "better" what prior translators had "left so good."

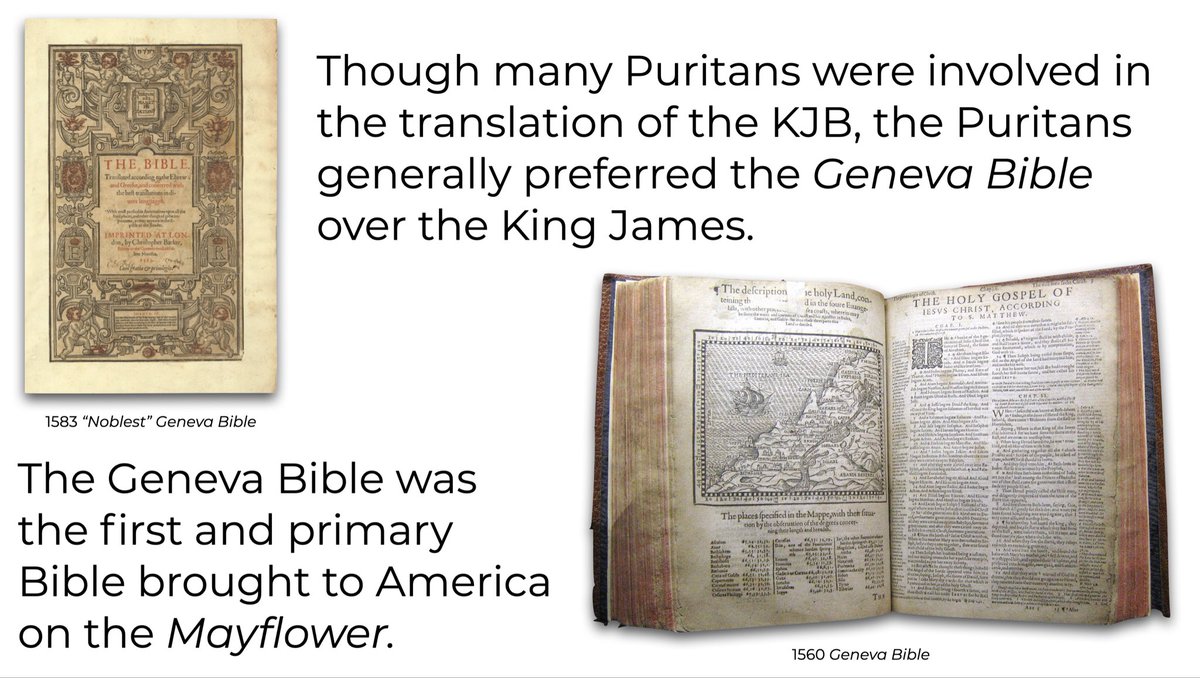

Though many Puritans were involved in the translation of the KJB, the Puritans generally preferred the Geneva Bible over the King James.

The Geneva Bible was the first and primary Bible brought to America on the Mayflower.

The Geneva Bible was the first and primary Bible brought to America on the Mayflower.

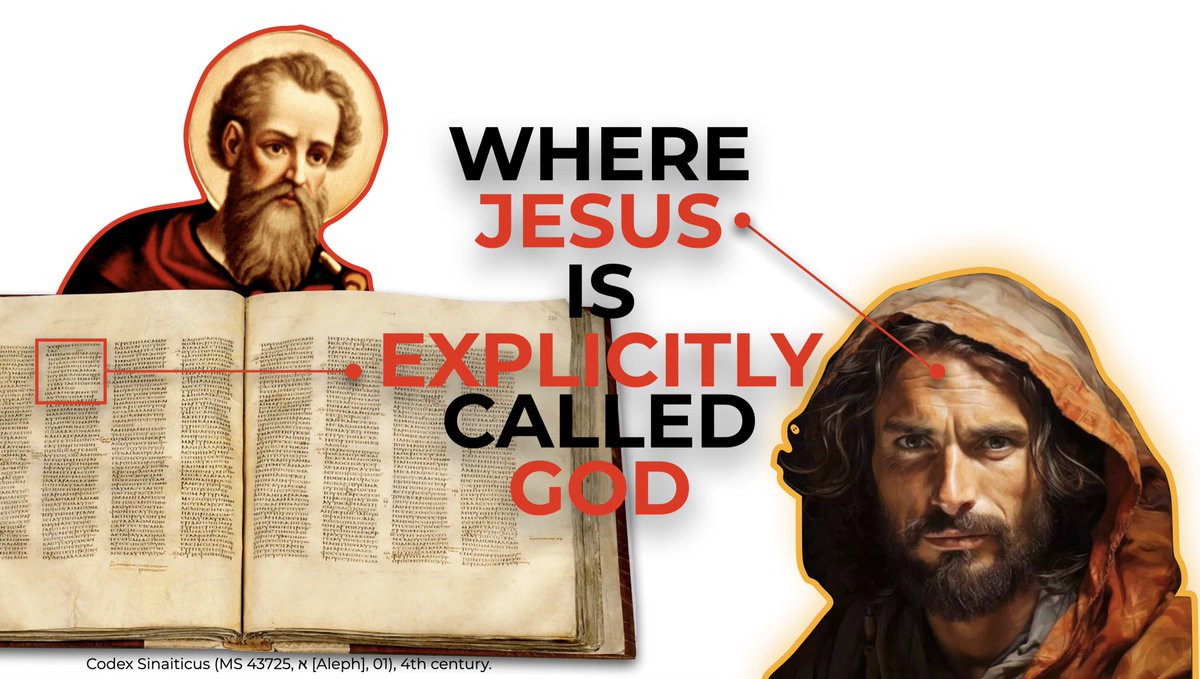

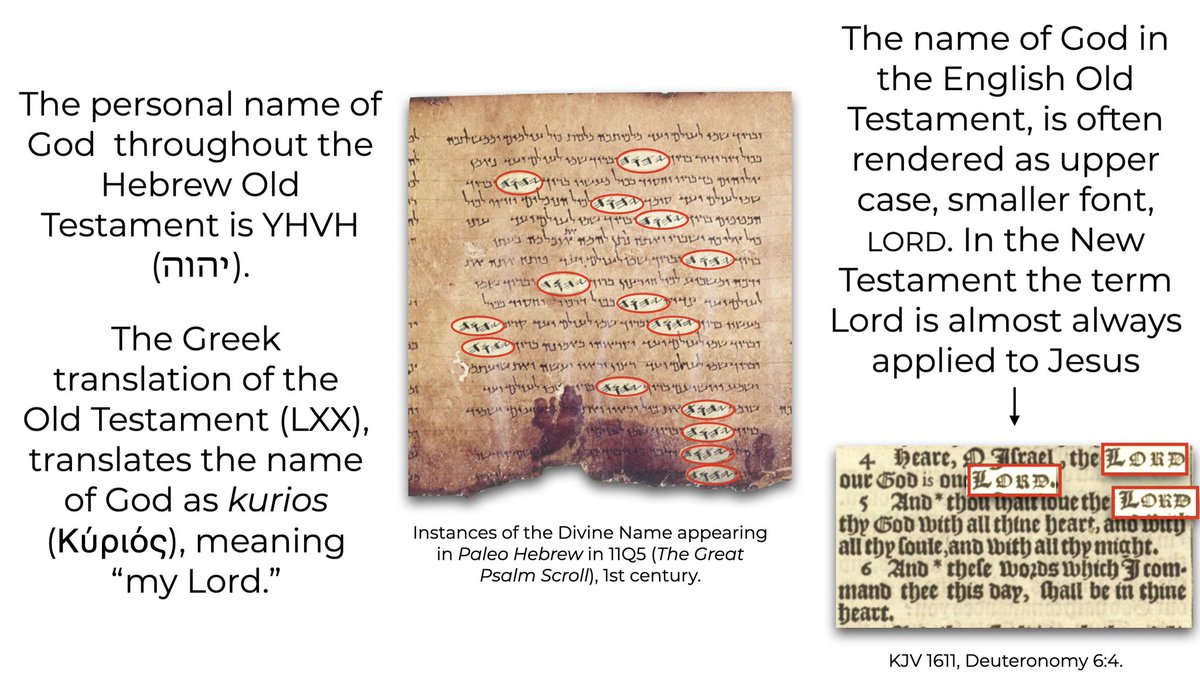

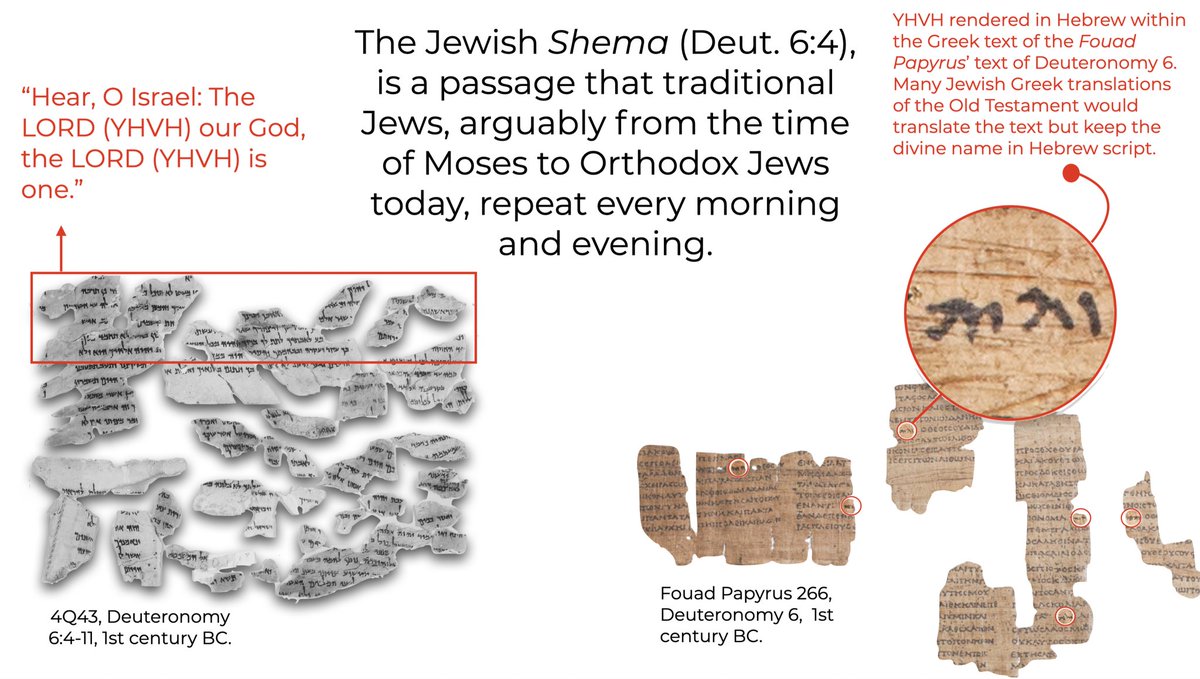

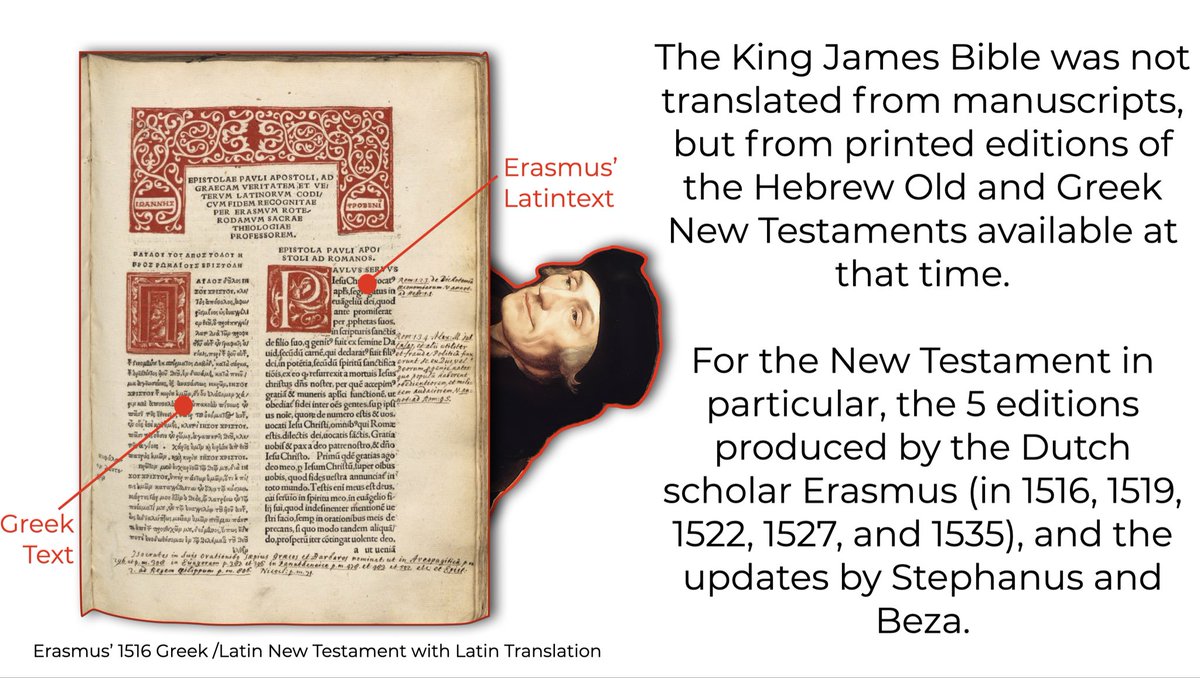

The King James Bible was not translated from manuscripts, but from printed editions of the Hebrew Old and Greek New Testaments available at that time. For the New Testament in particular, the 5 editions produced by the Dutch scholar Erasmus (in 1516, 1519, 1522, 1527, and 1535), and the updates by Stephanus and Beza.

What is typically called the "Textus

- Receptus" (TR) today is actually a work produced in 1894 by the English writer and scholar Frederick Scrivener. Scrivener looked at the translation choices made by the KJV translators and compiled them into a single volume. However, the KJV translators themselves were not dealing with a single document but multiple Texti Receipt (plural of Textus Receptus), mentioned previously.

- Receptus" (TR) today is actually a work produced in 1894 by the English writer and scholar Frederick Scrivener. Scrivener looked at the translation choices made by the KJV translators and compiled them into a single volume. However, the KJV translators themselves were not dealing with a single document but multiple Texti Receipt (plural of Textus Receptus), mentioned previously.

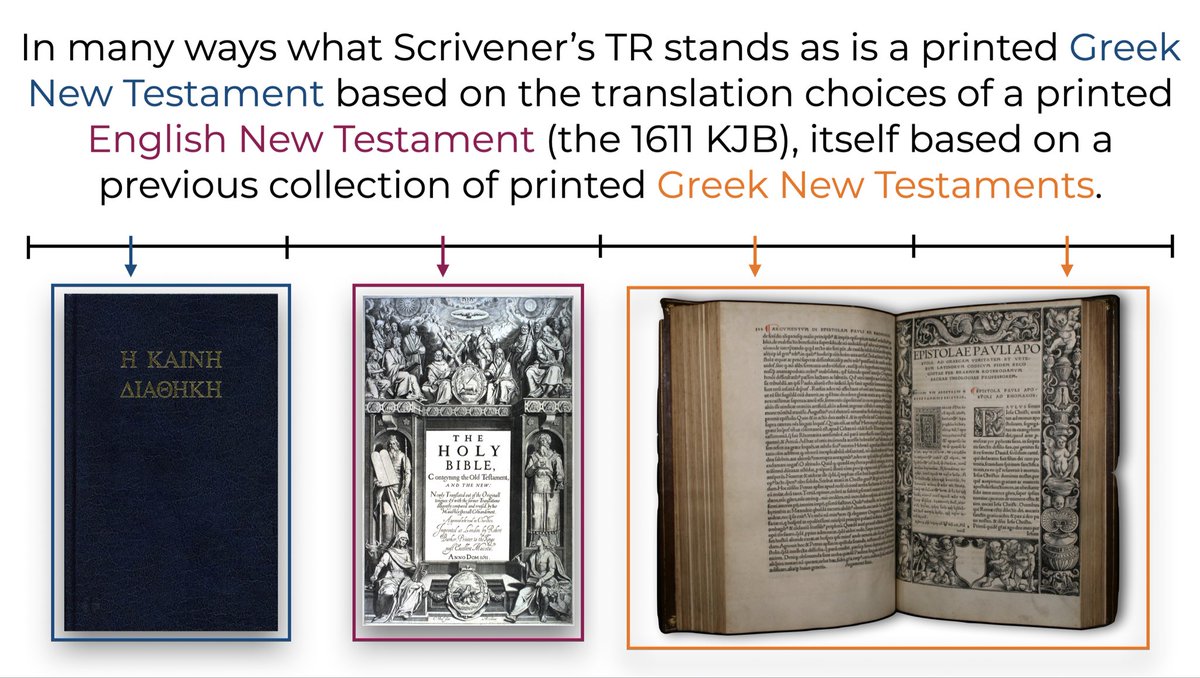

In many ways what Scrivener's TR stands as is a printed Greek New Testament based on the translation choices of a printed English New Testament (the 1611 KJB), itself based on a previous collection of printed Greek New Testaments.

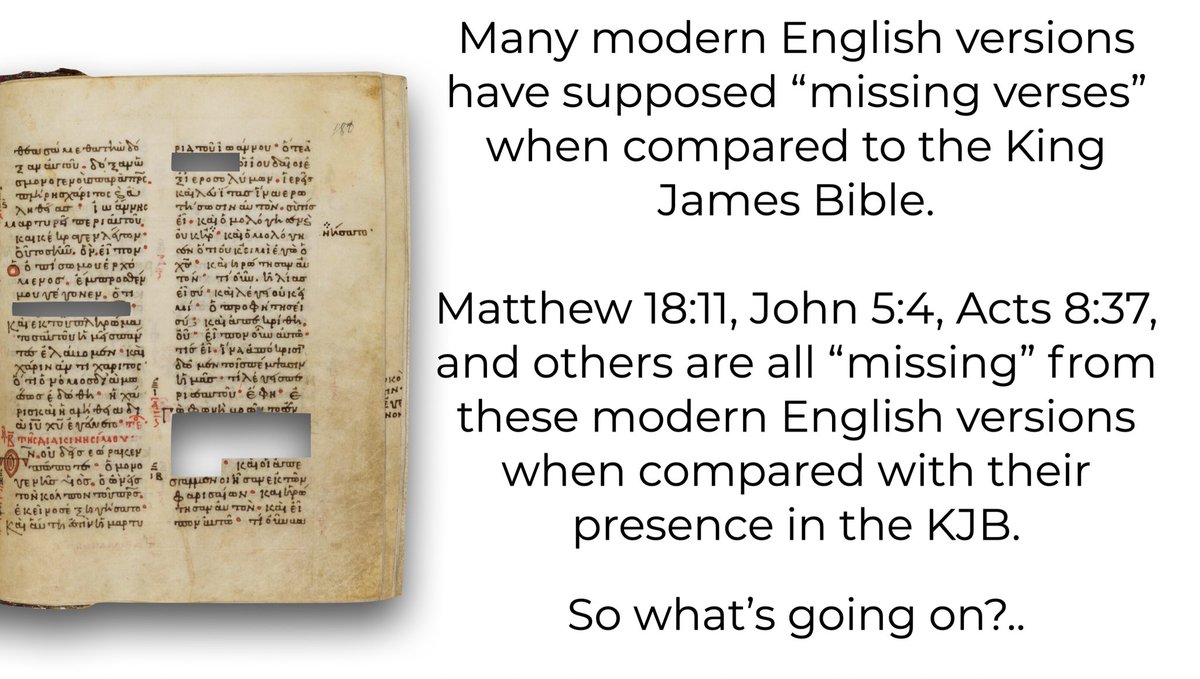

The KJV has also looked very different over the years. If you have a KJV today it is almost certainly not in the original 1611 English. There were revisions to the text in 1629, 1638, 1762, and 1769. If you own a King

James Bible today it is most likely a 1769 revision.

James Bible today it is most likely a 1769 revision.

Take a look at last week’s #manuscriptmonday

https://twitter.com/wesleylhuff/status/1978062697276047776

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh