When was the Qur'an canonized? Was it during Abdul al-Malik or Uthman? A Thread 🧵 | #quran #islam #islamicstudies #history (Part 2)

https://twitter.com/JordanAcademia0/status/1974514421377679382

@IslamicOrigins released a paper which goes over the arguments for & against both Uthmanic canonization, and Abd al-Malik canonization. I would like to go over them, and also add a bit of thoughts. Let's start off with the criticisms of Ḥajjājian Hypothesis ⬇doi.org/10.1515/jiqsa-…

Variations of the Ḥajjājian Hypothesis (H1–H4).

- H1 (Diacritics): Al-Ḥajjāj merely added diacritical markings to ʿUthmān’s canonical text (Nöldeke, David Margoliouth, Arthur Jeffery, Richard Bell, W. Montgomery Watt, Claude Gilliot, Omar Hamdan, and Herbert Berg).

- H2 (Corrections): Al-Ḥajjāj corrected errors in ʿUthmān’s consonantal canon and re-canonized the text (Jeffery, Blachère, and Déroche)

- H3 (Redaction/Re-canonization): Al-Ḥajjāj altered or redacted the contents of ʿUthmān’s consonantal canon and re-canonized it.

- H4 (Composition/Canonization): Al-Ḥajjāj, rather than ʿUthmān, produced the canonical consonantal text.

- H1 (Diacritics): Al-Ḥajjāj merely added diacritical markings to ʿUthmān’s canonical text (Nöldeke, David Margoliouth, Arthur Jeffery, Richard Bell, W. Montgomery Watt, Claude Gilliot, Omar Hamdan, and Herbert Berg).

- H2 (Corrections): Al-Ḥajjāj corrected errors in ʿUthmān’s consonantal canon and re-canonized the text (Jeffery, Blachère, and Déroche)

- H3 (Redaction/Re-canonization): Al-Ḥajjāj altered or redacted the contents of ʿUthmān’s consonantal canon and re-canonized it.

- H4 (Composition/Canonization): Al-Ḥajjāj, rather than ʿUthmān, produced the canonical consonantal text.

For H1 "Diacritics", this hypothesis has been variously criticized by Régis Blachère, De Prémare, Keith Small, François Déroche, Sinai, Dye, Adam Bursi, and Shoemaker, on two principal grounds (Blachère, Introduction, 77; De Prémare, Aux origines du Coran, 84; Small, Textual Criticism, 165; Déroche, Qurʾans of the Umayyads, 72, 96–97, 138; Sinai, “Part I,” 283–84 n64; Dye, “Pourquoi et com ment se fait un texte canonique?,” 63–64, 87; idem, “Le corpus coranique,” 890; Bursi, “Connecting the Dots,” 125–26, 128–29). Firstly, no matter how you look at it, the basic notion of a single, definitive, sweeping imposition of diacritics is inconsistent with the manuscript record: on the one hand, some diacritics are present already in the earliest manuscripts, rather than appearing abruptly at some secondary stage; and, on the other hand, their use remained sporadic or inconsistent in manuscripts long after the time of al-Ḥajjāj (Blachère, Introduction, 77; De Prémare, Aux origines du Coran, 84; idem, “ʿAbd al-Malik,” 204; Bursi, “Connecting the Dots,” 123–25). Secondly, the early Islamic sources are inconsistent on the question of who added diacritical markings to the Qur’an, with different sources naming different gov ernors and scribes in this regard (Blachère, Introduction, 77; De Prémare, Aux origines du Coran, 84; idem, “ʿAbd al-Malik,” 204; Bursi, “Connecting the Dots,” 123–25). In light of the foregoing, it seems reasonable to infer that the reports of al-Ḥajjāj’s being the one responsible for the addition of diacritics into codices of the canonical ʿUthmānic text-type ultimately reflect faulty guesswork, inferences, or speculation by later Muslim scholars, who sought–as in so many other cases–to identify a “great man” responsible for some specific aspect of their culture or society (Pace Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 809. See Little, “Where Did You Learn to Write Ara bic?,” 170–71).

To Respond to H2 "Textual Corrections",

if indeed al-Ḥajjāj commissioned the production of a copy of the Qur’an, and if indeed this copy contained the variants documented by ʿAwf, there is no reason to accept ʿAwf’s assertion that al-Ḥajjāj was responsible for the variants in question. On the contrary, these variants are consistent with being intra-ʿUthmānic developments: some or all of them may be the organic products of scribal error in the transmission of the canonical ʿUthmānic text-type; and some or all of them may derive from the original canonical ʿUthmānic text. Either way, there is no reason to credit such variants to al-Ḥajjāj (Sinai, “Part I,” 284 (incl. n65), and Van Putten and Sidky, “The Codices of Unknown Suc cessors.” Additionally, see Aʿẓamī, The History of the Qurʾānic Text, 102, who suggests that ʿAwf was motivated by hostility towards the Umayyads; and Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 799–800).

In other words, if indeed al-Ḥajjāj commissioned the production of a copy of the Qur’an, and if indeed this copy contained the variants documented by ʿAwf, there is no reason to accept ʿAwf’s assertion that al-Ḥajjāj was responsible for the variants in question. On the contrary, these variants are consistent with being intra-ʿUthmānic developments: some or all of them may be the organic products of scribal error in the transmission of the canonical ʿUthmānic text-type; and some or all of them may derive from the original canonical ʿUthmānic text. Either way, there is no reason to credit such variants to al-Ḥajjāj (Sinai, “Part I,” 284 (incl. n65), and Van Putten and Sidky, “The Codices of Unknown Suc cessors.” Additionally, see Aʿẓamī, The History of the Qurʾānic Text, 102, who suggests that ʿAwf was motivated by hostility towards the Umayyads; and Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 799–800).

if indeed al-Ḥajjāj commissioned the production of a copy of the Qur’an, and if indeed this copy contained the variants documented by ʿAwf, there is no reason to accept ʿAwf’s assertion that al-Ḥajjāj was responsible for the variants in question. On the contrary, these variants are consistent with being intra-ʿUthmānic developments: some or all of them may be the organic products of scribal error in the transmission of the canonical ʿUthmānic text-type; and some or all of them may derive from the original canonical ʿUthmānic text. Either way, there is no reason to credit such variants to al-Ḥajjāj (Sinai, “Part I,” 284 (incl. n65), and Van Putten and Sidky, “The Codices of Unknown Suc cessors.” Additionally, see Aʿẓamī, The History of the Qurʾānic Text, 102, who suggests that ʿAwf was motivated by hostility towards the Umayyads; and Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 799–800).

In other words, if indeed al-Ḥajjāj commissioned the production of a copy of the Qur’an, and if indeed this copy contained the variants documented by ʿAwf, there is no reason to accept ʿAwf’s assertion that al-Ḥajjāj was responsible for the variants in question. On the contrary, these variants are consistent with being intra-ʿUthmānic developments: some or all of them may be the organic products of scribal error in the transmission of the canonical ʿUthmānic text-type; and some or all of them may derive from the original canonical ʿUthmānic text. Either way, there is no reason to credit such variants to al-Ḥajjāj (Sinai, “Part I,” 284 (incl. n65), and Van Putten and Sidky, “The Codices of Unknown Suc cessors.” Additionally, see Aʿẓamī, The History of the Qurʾānic Text, 102, who suggests that ʿAwf was motivated by hostility towards the Umayyads; and Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 799–800).

For al-Ḥajjāj and (re-)canonization (Ḥ3–4) (On the canonization by al-Hajjaj), there are three main Christian sources that proponents of the Ḥajjājian canon ization and re-canonization hypotheses have variously cited as direct evidence for their respective positions:

- Łewond’s Armenian translation and redaction of The Correspondence of Leo III and ʿUmar II, an earlier Palestinian Christian work

- The Disputation of the Monk Abraham of Tiberias, a Palestinian Arabic Christian work that takes the form of a debate between a Tiberian monk named Abraham and an Arab Muslim official named ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Hāshimī, which has been dated to the early-ninth century CE

- The Letter of ʿAbd al-Masīḥ al-Kindī to ʿAbd Allāh b. Ismāʿīl al-Hāshimī, an Arabic Christian epistolic work that has been variously dated to the time of the Abbasid caliph al-Maʾmūn (r. 198–218/813–833)

- The Affair of the Qur’an, a short Syriac Christian composition that possibly dates from the eighth or ninth century CE.

- Łewond’s Armenian translation and redaction of The Correspondence of Leo III and ʿUmar II, an earlier Palestinian Christian work

- The Disputation of the Monk Abraham of Tiberias, a Palestinian Arabic Christian work that takes the form of a debate between a Tiberian monk named Abraham and an Arab Muslim official named ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Hāshimī, which has been dated to the early-ninth century CE

- The Letter of ʿAbd al-Masīḥ al-Kindī to ʿAbd Allāh b. Ismāʿīl al-Hāshimī, an Arabic Christian epistolic work that has been variously dated to the time of the Abbasid caliph al-Maʾmūn (r. 198–218/813–833)

- The Affair of the Qur’an, a short Syriac Christian composition that possibly dates from the eighth or ninth century CE.

However, they could just as easily embody a common Christian polemical distortion of the Qur’an’s history, as scholars like Jeffery, Harald Motzki, and Sinai have suggested (Jeffery, “Ghevond’s Text,” 298 n48; Motzki, “Collection,” 14, 20; Sinai, “Part I,” 284. See also Nöldeke et al., Geschichte des Qorāns, 3:104 n1 [= The History of the Qurʾān, 462–63 n604]; Déroche, The One and the Many, 132–33). In other words, we could easily be dealing here with a false Christian allegation born from a misunderstanding or exaggeration of al-Ḥajjāj’s involvement with the Qur’an–that emerged in a Christian intellectual center like Palestine at some point in the eighth century CE and thence spread to Armenia and other regions. For Palestine as a root node for early Christian apologies and polemics against Islam, espe cially in relation to Armenia, see Palombo, “The ‘Correspondence’ of Leo III and ʿUmar II,” 259, 264; Shoemaker, A Prophet Has Appeared, 62–63, 219; Roohi, Pseudo-Sebēos on Muslim-Jewish Intimacy. 106 Casanova, Mohammed, 119; Mingana, “The Transmission of the Kurʾān According to Christian Writers,” 407; Shoemaker, Creating the Qurʾan, 53–58. Indeed, the strong arguments outlined above in favor of the ʿUthmānic hypothesis, and those outlined below against the Ḥajjājian hypothesis, precisely give us a reason to adopt such an explanation for the data.

To defend the reliability of these Christian sources, Casanova, Mingana, and Shoemaker have all appealed to their relative earliness, though such an appeal fails on two counts. Firstly, as Motzki has noted and Shoemaker also seems to acknowledge, an earlier source is not necessarily a more reliable source (Motzki, “Collection,” 14; Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet, 148–49). Secondly, the Christian sources in question are not actually particularly early: The Armenian redaction of the Letter of Leo, which is the earliest of the four, has only been vaguely dated to the eighth century CE at the earliest. By contrast, Motzki has demonstrated that at least one version of the ʿUthmānic narrative can be confidently traced back to a Muslim source–Ibn Shihāb al-Zuhrī–who died in 123–125/740–743 (Motzki, “Collection,” reiterated in Sinai, “Part I,” 282). In other words, if this debate comes down to a contest over the earliest securely dated report of the Qur’an’s canonizer, then the ʿUthmānic hypoth esis clearly has the edge.

To defend the reliability of these Christian sources, Casanova, Mingana, and Shoemaker have all appealed to their relative earliness, though such an appeal fails on two counts. Firstly, as Motzki has noted and Shoemaker also seems to acknowledge, an earlier source is not necessarily a more reliable source (Motzki, “Collection,” 14; Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet, 148–49). Secondly, the Christian sources in question are not actually particularly early: The Armenian redaction of the Letter of Leo, which is the earliest of the four, has only been vaguely dated to the eighth century CE at the earliest. By contrast, Motzki has demonstrated that at least one version of the ʿUthmānic narrative can be confidently traced back to a Muslim source–Ibn Shihāb al-Zuhrī–who died in 123–125/740–743 (Motzki, “Collection,” reiterated in Sinai, “Part I,” 282). In other words, if this debate comes down to a contest over the earliest securely dated report of the Qur’an’s canonizer, then the ʿUthmānic hypoth esis clearly has the edge.

From Casanova onwards, pro-Ḥajjājian scholars have appealed to various reports preserved in Islamic sources that apparently depict al-Ḥajjāj’s canoni zation or re-canonization of the Qur’an under ʿAbd al-Malik.

However, none of these reports state that al-Ḥajjāj’s efforts to suppress non-canonical versions of the Qur’an were part of a canonization–or for that matter, redaction or collection–process that he himself had initiated (De Prémare, “ʿAbd al-Malik,” 209–10, and Shoemaker, Creating the Qurʾan, 49, also cite Ibn ʿAsākir, Taʾrīkh, 12:159–60 ← al-Laftuwānī ← Muḥammad b. Aḥmad and Sulaymān b. Ibrāhīm ← al-Burjī ← al-Jūrijīrī ← Isḥāq b. al-Fayḍ ← Ibn Ḥumayd ← Jarīr ← ʿAṭāʾ b. al-Sāʾib ← ʿAttāb b. Usayd).

On the contrary, all of them read perfectly well as witnesses to a consistent Umayyad policy of maintaining the ʿUthmānic canonization at the expense of a non-ʿUthmānic version of the Qur’an that lingered on in some Kufan circles. Indeed, this is how many scholars–including Gotthelf Bergsträßer, Otto Pretzl, Hamdan, and Sinai–have interpreted such reports (Nöldeke et al., Geschichte des Qorāns, 3:104 n1 [= The History of the Qurʾān, 462–63 n604]; Aʿẓamī, The History of the Qurʾānic Text, 103–4; Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 798 99, 823–24, and passim; Sinai, “Part I,” 281, 283. Additionally, see Judd, “Al-Hağğāğ b. Yūsuf,” 53 ff., 57. For the Kufan resistance to the ʿUthmānic text-type more broadly, see also Nöldeke and Schwally, Geschichte des Qorāns, II, 49 [= The History of the Qurʾān, 252]; Jeffery, Materials, 8; Blachère, Intro duction, 63–64; Jones, “The Qurʾān–II,” 241).

However, none of these reports state that al-Ḥajjāj’s efforts to suppress non-canonical versions of the Qur’an were part of a canonization–or for that matter, redaction or collection–process that he himself had initiated (De Prémare, “ʿAbd al-Malik,” 209–10, and Shoemaker, Creating the Qurʾan, 49, also cite Ibn ʿAsākir, Taʾrīkh, 12:159–60 ← al-Laftuwānī ← Muḥammad b. Aḥmad and Sulaymān b. Ibrāhīm ← al-Burjī ← al-Jūrijīrī ← Isḥāq b. al-Fayḍ ← Ibn Ḥumayd ← Jarīr ← ʿAṭāʾ b. al-Sāʾib ← ʿAttāb b. Usayd).

On the contrary, all of them read perfectly well as witnesses to a consistent Umayyad policy of maintaining the ʿUthmānic canonization at the expense of a non-ʿUthmānic version of the Qur’an that lingered on in some Kufan circles. Indeed, this is how many scholars–including Gotthelf Bergsträßer, Otto Pretzl, Hamdan, and Sinai–have interpreted such reports (Nöldeke et al., Geschichte des Qorāns, 3:104 n1 [= The History of the Qurʾān, 462–63 n604]; Aʿẓamī, The History of the Qurʾānic Text, 103–4; Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 798 99, 823–24, and passim; Sinai, “Part I,” 281, 283. Additionally, see Judd, “Al-Hağğāğ b. Yūsuf,” 53 ff., 57. For the Kufan resistance to the ʿUthmānic text-type more broadly, see also Nöldeke and Schwally, Geschichte des Qorāns, II, 49 [= The History of the Qurʾān, 252]; Jeffery, Materials, 8; Blachère, Intro duction, 63–64; Jones, “The Qurʾān–II,” 241).

Pro-Ḥajjājian scholars like Casanova, Mingana, De Prémare, Powers, Amir Moezzi, Kohlberg, Dye, and Shoemaker have also appealed to a series of reports about al-Ḥajjāj’s commissioning the production of qur’anic codices (maṣāḥif), and of his sending these codices to various provinces.

Once again, however, none of these reports state that al-Ḥajjāj canonized–let alone collected–the Qur’an. Indeed, all three reports are ostensibly inconsistent with such an interpretation. In the first case, Ibn Zabālah’s report speaks of al-Ḥajjāj’s sending maṣāḥif in the same terms and in the same breath as it speaks of al-Mahdī’s sending maṣāḥif, which immediately suggests–unless we suppose a third canonization sce nario under the Abbasids–that we are dealing in both cases with the sending of fresh copies of the Qur’an, not of new versions (Contra Dye, “Pourquoi et comment se fait un texte canonique?,” 64; idem, “Le corpus coranique,” 859. See also Sinai, “Part I,” 280–81). In the second case, Ibn Shabbah’s report explicitly refers to the ʿUthmānic canonization, and further observes that al-Mahdī’s muṣḥaf replaced al-Ḥajjāj’s muṣḥaf in the main mosque of Medina, which reinforces the notion that we are simply dealing with the sending of fresh copies of the Qur’an by successive Muslim patrons (Sadeghi and Bergmann, “Codex,” 365 n36). 3 In the third case, Ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥakam reported that al-Ḥajjāj’s sending of a muṣḥaf to Egypt was countermanded by the local gover nor, which immediately suggests that we are dealing with something other than a state-backed canonization, as Sinai has noted (Sinai, “Part I,” 285); and that Egypt already possessed a community of Qur’an-reciters intimately familiar with the canonical text, which implies that the Qur’an had already been canonized previously (Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 824).

Once again, however, none of these reports state that al-Ḥajjāj canonized–let alone collected–the Qur’an. Indeed, all three reports are ostensibly inconsistent with such an interpretation. In the first case, Ibn Zabālah’s report speaks of al-Ḥajjāj’s sending maṣāḥif in the same terms and in the same breath as it speaks of al-Mahdī’s sending maṣāḥif, which immediately suggests–unless we suppose a third canonization sce nario under the Abbasids–that we are dealing in both cases with the sending of fresh copies of the Qur’an, not of new versions (Contra Dye, “Pourquoi et comment se fait un texte canonique?,” 64; idem, “Le corpus coranique,” 859. See also Sinai, “Part I,” 280–81). In the second case, Ibn Shabbah’s report explicitly refers to the ʿUthmānic canonization, and further observes that al-Mahdī’s muṣḥaf replaced al-Ḥajjāj’s muṣḥaf in the main mosque of Medina, which reinforces the notion that we are simply dealing with the sending of fresh copies of the Qur’an by successive Muslim patrons (Sadeghi and Bergmann, “Codex,” 365 n36). 3 In the third case, Ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥakam reported that al-Ḥajjāj’s sending of a muṣḥaf to Egypt was countermanded by the local gover nor, which immediately suggests that we are dealing with something other than a state-backed canonization, as Sinai has noted (Sinai, “Part I,” 285); and that Egypt already possessed a community of Qur’an-reciters intimately familiar with the canonical text, which implies that the Qur’an had already been canonized previously (Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 824).

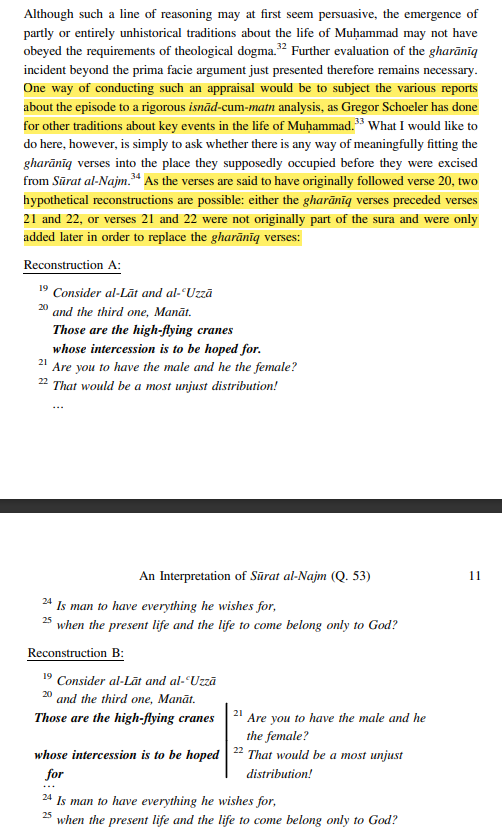

Finally, pro-Ḥajjājian scholars like Mingana, De Prémare, Dye, and Shoemaker have also appealed to a series of miscellaneous reports that putatively describe some kind of collection, composition, or redaction of the Qur’an by ʿAbd al-Malik and/or al-Ḥajjāj.

The first of these reports, which can be traced–by means of an isnād-cum-matn analysis–back to the early Kufan “partial common link” (PCL) ʿAlī b. Mushir, has been interpreted by De Prémare, Dye, and Shoemaker as an account of al-Ḥajjāj’s ordering a team of scribes to collect or compose the Qur’an, bringing together hith erto-discrete sūrahs to form the canonical text. It is certainly true that al-Ḥajjāj’s use of the term taʾlīf (“to compose”) immediately suggests that we are dealing with the collection or creation of a text, but other elements in the narrative militate against such an interpretation: al-Ḥajjāj is clearly addressing the Kufan public in a Friday sermon, not a scriptorium, as Sinai has pointed out (Sinai, “Part I,” 283. Similarly, Fudge, “Scepticism as Method,” 12); the peculiar differ ence between al-Ḥajjāj’s phrasing (“the sūrah in which the cow is mentioned”) and Ibn Masʿūd’s (“the Sūrah of the Cow”) remains unexplained on De Prémare’s interpretation; and the entire second half of the narrative seems completely irrelevant. Against De Prémare et al., Sinai has suggested that this report instead reflects an early debate over the proper order of the qur’anic text. There is certainly something to this view: In ʿAlī b. Mushir’s original formulation, al-Ḥajjāj refers to al-Baqarah, then Āl ʿImrān, then al-Nisāʾ (Contra ʿIyāḍ, Sharḥ, 4:372–73; De Prémare, “ʿAbd al-Malik,” 207; Dye, “Pourquoi et comment se fait un texte canonique?,” 90, 92; and Fudge, “Scepticism as Method,” 12), which notably corresponds to the ʿUthmānic sūrah-order, in contradistinction to the famous Ibn Masʿūdic order of al-Baqarah, then al-Nisāʾ, then Āl ʿImrān (Jeffery, Materials, 20–24).

The first of these reports, which can be traced–by means of an isnād-cum-matn analysis–back to the early Kufan “partial common link” (PCL) ʿAlī b. Mushir, has been interpreted by De Prémare, Dye, and Shoemaker as an account of al-Ḥajjāj’s ordering a team of scribes to collect or compose the Qur’an, bringing together hith erto-discrete sūrahs to form the canonical text. It is certainly true that al-Ḥajjāj’s use of the term taʾlīf (“to compose”) immediately suggests that we are dealing with the collection or creation of a text, but other elements in the narrative militate against such an interpretation: al-Ḥajjāj is clearly addressing the Kufan public in a Friday sermon, not a scriptorium, as Sinai has pointed out (Sinai, “Part I,” 283. Similarly, Fudge, “Scepticism as Method,” 12); the peculiar differ ence between al-Ḥajjāj’s phrasing (“the sūrah in which the cow is mentioned”) and Ibn Masʿūd’s (“the Sūrah of the Cow”) remains unexplained on De Prémare’s interpretation; and the entire second half of the narrative seems completely irrelevant. Against De Prémare et al., Sinai has suggested that this report instead reflects an early debate over the proper order of the qur’anic text. There is certainly something to this view: In ʿAlī b. Mushir’s original formulation, al-Ḥajjāj refers to al-Baqarah, then Āl ʿImrān, then al-Nisāʾ (Contra ʿIyāḍ, Sharḥ, 4:372–73; De Prémare, “ʿAbd al-Malik,” 207; Dye, “Pourquoi et comment se fait un texte canonique?,” 90, 92; and Fudge, “Scepticism as Method,” 12), which notably corresponds to the ʿUthmānic sūrah-order, in contradistinction to the famous Ibn Masʿūdic order of al-Baqarah, then al-Nisāʾ, then Āl ʿImrān (Jeffery, Materials, 20–24).

Arguments Against the ʿUthmānic Hypothesis 🧵 (¬U1–¬U7) revisionists argue against ʿUthmān based on: (¬U1) the late timeframe of Jewish/Christian canonization; (¬U2) absence of necessary state infrastructure in ʿUthmān’s time; (¬U3) absence of Qur’an references in early non-Islamic and Islamic contexts; (¬U4) differing Qur’anic inscriptions on the Dome of the Rock (691 CE); (¬U5) contradictory descriptions by John of Damascus (early 8th century); (¬U6) the Disputation between a Muslim and a Monk of Bēt Ḥālē; and (¬U7) the P. Hamb. Arab. 68 manuscript.

¬U2 fails because developed Arabic writing existed pre-ʿUthmān, and the empire was concentrated enough for logistics.

Firstly, Nabia Abbott, Petra Sijpesteijn, and Van Putten have all variously shown–on the basis of early Arabic papyri, inscriptions, and orthography–that a developed tradition of Arabic writing and even a developed Arabic bureaucratic tradition existed prior to ʿUthmān (Abbott, The Rise of the North Arabic Script, 48; Sijpesteijn, “Arabic Script and Language in the Earliest Papyri”; Van Putten, “The Development of the Hijazi Orthography,” esp. 125–26 (explicitly responding to Shoemaker). Cf. Shoemaker, Quest, 51 n181, but cf. in turn Macdonald and al-Jallad, “Literacy in 6th and 7th Century Hijaz.”). (To this can be added the fact, already admitted by Mingana, that Christian and Jewish scribes were readily available for Muslim employment at the outset (Mingana, “The Transmission of the Kurʾān According to Christian Writers,” 413). Secondly, as both Robert Hoyland and Cook have pointed out, early Christian sources and later Islamic sources agree that, already in the time of ʿUmar (r. 13–23/634–644), there existed a central government with the power to appoint, dismiss, and coordinate governors and generals across the early Arab empire (Hoyland, “New Documentary Texts,” esp. 398–99; Cook, A History of the Muslim World, 97–101. See also Crone, “The Early Islamic World,” 311).

To the foregoing can be added the consideration that most Muslims remained concentrated in a small number of cities and regions during the time of ʿUthmān (E. g., Crone, “The Early Islamic World,” 311–12), making it that much easier for him to execute his canonization. . In fact, ʿUthmān perfectly targeted the most populous and influential Muslim centers, which could–and evidently did–act as parent nodes in the copying and dissemination of the canonical Qur’an. In other words, whilst there is no doubt that ʿUthmān’s government was weaker than Muʿāwiyah’s, ʿAbd al-Malik’s, or al-Maʾmūn’s, the socio-political conditions of ʿUthmān’s time were far more favorable or conducive to a canonization project in this key respect. Moreover, whilst it is true that ʿUthmān faced popular unrest towards the end of his reign, this still leaves the beginning and middle thereof as viable points at which he could have carried out his canonization project, as is indeed explicitly indicated by some reports. What then is missing, in terms of power, infrastructure, tech nology, and logistics, for a canonization of the Qur’an during the reign of ʿUthmān? Skeptics of the ʿUthmānic canonization seem to be creating problems where none exist.

Firstly, Nabia Abbott, Petra Sijpesteijn, and Van Putten have all variously shown–on the basis of early Arabic papyri, inscriptions, and orthography–that a developed tradition of Arabic writing and even a developed Arabic bureaucratic tradition existed prior to ʿUthmān (Abbott, The Rise of the North Arabic Script, 48; Sijpesteijn, “Arabic Script and Language in the Earliest Papyri”; Van Putten, “The Development of the Hijazi Orthography,” esp. 125–26 (explicitly responding to Shoemaker). Cf. Shoemaker, Quest, 51 n181, but cf. in turn Macdonald and al-Jallad, “Literacy in 6th and 7th Century Hijaz.”). (To this can be added the fact, already admitted by Mingana, that Christian and Jewish scribes were readily available for Muslim employment at the outset (Mingana, “The Transmission of the Kurʾān According to Christian Writers,” 413). Secondly, as both Robert Hoyland and Cook have pointed out, early Christian sources and later Islamic sources agree that, already in the time of ʿUmar (r. 13–23/634–644), there existed a central government with the power to appoint, dismiss, and coordinate governors and generals across the early Arab empire (Hoyland, “New Documentary Texts,” esp. 398–99; Cook, A History of the Muslim World, 97–101. See also Crone, “The Early Islamic World,” 311).

To the foregoing can be added the consideration that most Muslims remained concentrated in a small number of cities and regions during the time of ʿUthmān (E. g., Crone, “The Early Islamic World,” 311–12), making it that much easier for him to execute his canonization. . In fact, ʿUthmān perfectly targeted the most populous and influential Muslim centers, which could–and evidently did–act as parent nodes in the copying and dissemination of the canonical Qur’an. In other words, whilst there is no doubt that ʿUthmān’s government was weaker than Muʿāwiyah’s, ʿAbd al-Malik’s, or al-Maʾmūn’s, the socio-political conditions of ʿUthmān’s time were far more favorable or conducive to a canonization project in this key respect. Moreover, whilst it is true that ʿUthmān faced popular unrest towards the end of his reign, this still leaves the beginning and middle thereof as viable points at which he could have carried out his canonization project, as is indeed explicitly indicated by some reports. What then is missing, in terms of power, infrastructure, tech nology, and logistics, for a canonization of the Qur’an during the reign of ʿUthmān? Skeptics of the ʿUthmānic canonization seem to be creating problems where none exist.

¬U1 fails because Muslims consciously followed the existing model of scriptures and had state power, unlike Jews/Christians.

the relative rapidity of the Muslim process of compilation and canonization–compared to the Bible–has already been explained, on two grounds. Firstly, as Nöldeke, Schwally, and Cook have all pointed out, Muḥammad and his followers lived in the aftermath of the establishment of the Jewish and Christian scriptures and explicitly operated with this concept or model in mind, which helps to explain the Muslim preoccupation with establishing a scripture of their own from the outset (Nöldeke and Schwally, Geschichte des Qorāns, 2:119–21 [= The History of the Qurʾān, 311–13]; Cook, The Koran, 123). Secondly, as Cook has again pointed out, the early Muslims who canonized the Qur’an already had access to, and evidently made use of, a state, in contrast to their Jewish and Christian predecessors (Cook, The Koran, 123–24; Muir, The Life of Muhammad, 1:xiv xv; Nöldeke, Sketches, 53–54; Caetani, Annali dell’Islam, 7:417 [= “ʿUthman and the Recension of the Koran,” 389]; Lammens, L’Islam, 44–45 [= Islam, 38]; Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 829–30; Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet, 158; idem, Creating the Qurʾan, 37, 205). In light of these clear histor ical and contextual disanalogies, the belated process of biblical canonization–vari ously adduced by Mingana, Robinson, and Shoemaker–becomes irrelevant.

the relative rapidity of the Muslim process of compilation and canonization–compared to the Bible–has already been explained, on two grounds. Firstly, as Nöldeke, Schwally, and Cook have all pointed out, Muḥammad and his followers lived in the aftermath of the establishment of the Jewish and Christian scriptures and explicitly operated with this concept or model in mind, which helps to explain the Muslim preoccupation with establishing a scripture of their own from the outset (Nöldeke and Schwally, Geschichte des Qorāns, 2:119–21 [= The History of the Qurʾān, 311–13]; Cook, The Koran, 123). Secondly, as Cook has again pointed out, the early Muslims who canonized the Qur’an already had access to, and evidently made use of, a state, in contrast to their Jewish and Christian predecessors (Cook, The Koran, 123–24; Muir, The Life of Muhammad, 1:xiv xv; Nöldeke, Sketches, 53–54; Caetani, Annali dell’Islam, 7:417 [= “ʿUthman and the Recension of the Koran,” 389]; Lammens, L’Islam, 44–45 [= Islam, 38]; Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 829–30; Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet, 158; idem, Creating the Qurʾan, 37, 205). In light of these clear histor ical and contextual disanalogies, the belated process of biblical canonization–vari ously adduced by Mingana, Robinson, and Shoemaker–becomes irrelevant.

¬U3 is explained by early Christian disinterest and the Qur'an initially being treated ritually by Muslims.

Mingana’s, Wansbrough’s, Dye’s, and Shoemaker’s various appeals (¬U3) to the absence of references to the Qur’an in the first/seventh century have also been criti cized. Firstly, Abbott has explained the early Christian silence thereon by arguing that early Christians were frequently uninterested in their new Muslim overlords and mis informed even regarding basic facts about them, making the early Christian failure to refer to the Qur’an unsurprising (Abbott, The Rise of the North Arabic Script, 48). Secondly, Sinai has explained the apparent failure of early Muslims to rely on the Qur’an in matters of doctrine by arguing that the Qur’an was not readily available to most Muslims in the early period; that most early Muslims possessed only a superficial knowledge of its contents; and that the Qur’an was initially treated more as a ritual object than a programmatic source of doctrine (Sinai, “Part I,” 289–91. For more on the idea that the Qur’an was initially treated more as a sacred or ritual object, see Madigan, The Qurʾân’s Self-Image, 50–52 (incl. n137). For more on the early Mus lim ignorance of, or lack of access to, the Qur’an, see Caetani, Annali dell’Islam, 7:415 [= “ʿUthman and the Recension of the Koran,” 387–88]; Nöldeke et al., Geschichte des Qorāns, 3:119 [= The History of the Qurʾān, 473]; Kister, “…Illā Bi-Ḥaqqihi…,” 51; Bulliet, Islam, 28–31; Cook, The Koran, 137–38; Donner, “From Believers to Muslims,” 26–27; idem, Muhammad, 77; Sinai, “The Unknown Known,” 80; Tannous, The Making of the Medieval Middle East, passim; etc).

Mingana’s, Wansbrough’s, Dye’s, and Shoemaker’s various appeals (¬U3) to the absence of references to the Qur’an in the first/seventh century have also been criti cized. Firstly, Abbott has explained the early Christian silence thereon by arguing that early Christians were frequently uninterested in their new Muslim overlords and mis informed even regarding basic facts about them, making the early Christian failure to refer to the Qur’an unsurprising (Abbott, The Rise of the North Arabic Script, 48). Secondly, Sinai has explained the apparent failure of early Muslims to rely on the Qur’an in matters of doctrine by arguing that the Qur’an was not readily available to most Muslims in the early period; that most early Muslims possessed only a superficial knowledge of its contents; and that the Qur’an was initially treated more as a ritual object than a programmatic source of doctrine (Sinai, “Part I,” 289–91. For more on the idea that the Qur’an was initially treated more as a sacred or ritual object, see Madigan, The Qurʾân’s Self-Image, 50–52 (incl. n137). For more on the early Mus lim ignorance of, or lack of access to, the Qur’an, see Caetani, Annali dell’Islam, 7:415 [= “ʿUthman and the Recension of the Koran,” 387–88]; Nöldeke et al., Geschichte des Qorāns, 3:119 [= The History of the Qurʾān, 473]; Kister, “…Illā Bi-Ḥaqqihi…,” 51; Bulliet, Islam, 28–31; Cook, The Koran, 137–38; Donner, “From Believers to Muslims,” 26–27; idem, Muhammad, 77; Sinai, “The Unknown Known,” 80; Tannous, The Making of the Medieval Middle East, passim; etc).

¬U4 (Dome of the Rock) and ¬U5/¬U6 (Christian sources) is susceptible to interpretation as selected quotations or Christian misunderstandings.

De Prémare, Robinson, Shoemaker, and Dye’s appeal (¬U4) to the Dome of the Rock has also been criticized by Sinai, who points out–following Estelle Whelan–that the Dome’s inscriptions can be interpreted as nothing more than quotations from the canonical Qur’an that have been selected, slightly paraphrased in places, and combined with honorific formulae to form a coherent (pro-Islamic and anti-Chris tian) message ( Sinai, “Part I,” 277–78, citing Whelan, “Forgotten Witness.” As Whelan (ibid., 6–8) ). In other words, these inscriptions constitute equivocal evidence, being compatible with, or explicable on, either view (Cook, The Koran, 119–20.).

Sinai has also criticized De Prémare, Dye, and Shoemaker’s appeal (¬U5) to John of Damascus, on two grounds. Firstly, for all that De Prémare et al. insist on John’s reliability (E. g., Dye, “Pourquoi et comment se fait un texte canonique?,” 94; Shoemaker, Creating the Qurʾan, 50–52. See also De Prémare, “ʿAbd al-Malik,” 197), it would really come as no surprise if John–a hostile writer dealing with a rival religious tradition–was simply misinformed about the precise contents and arrangement of the Qur’an and/or erred in his recounting thereof, or in other words: John’s testimony is highly equivocal evidence (Sinai, “Part I,” 286–87. For more on the debate over John’s reliability and his sources, see Becker, “Christian Polemic,” 244–47/4–7; Merrill, “Of the Tractate of John of Damascus on Islam”; Mey endorff, “Byzantine Views of Islam,” esp. 118; Sahas, John of Damascus, ch. 5; Hoyland, Seeing Islam, 488–89 (incl. n116); Louth, St John Damascene, 79–81; Popov, “Speaking His Mind”; Neil, “The Earliest Greek Understandings of Islam,” 220–22; Schadler, John of Damascus, chs. 3–4).

Secondly, De Prémare et al. posit that al-Ḥajjāj disseminated the canonical qur’anic text-type and ruthlessly purged any and all prior qur’anic texts and traditions c. 700 CE; yet John, who was writing in the 730s CE or later, apparently still had access to pre-canonical (or as De Prémare et al. would have it, pre-Ḥajjājian) qur’anic texts and traditions. This poses an obvious problem for De Prémare et al.: If John was writing three decades or more after the Ḥajjājian canonization, why were the effects thereof not at all evident in John’s writing? (Sinai, "Part I" 287). In other words, even for proponents of the Ḥajjājian hypothesis, there is a reason to suppose that John was really just referring to the canonical (or, as De Prémare et al. would have it, the Ḥajjājian) text-type.

De Prémare, Robinson, Shoemaker, and Dye’s appeal (¬U4) to the Dome of the Rock has also been criticized by Sinai, who points out–following Estelle Whelan–that the Dome’s inscriptions can be interpreted as nothing more than quotations from the canonical Qur’an that have been selected, slightly paraphrased in places, and combined with honorific formulae to form a coherent (pro-Islamic and anti-Chris tian) message ( Sinai, “Part I,” 277–78, citing Whelan, “Forgotten Witness.” As Whelan (ibid., 6–8) ). In other words, these inscriptions constitute equivocal evidence, being compatible with, or explicable on, either view (Cook, The Koran, 119–20.).

Sinai has also criticized De Prémare, Dye, and Shoemaker’s appeal (¬U5) to John of Damascus, on two grounds. Firstly, for all that De Prémare et al. insist on John’s reliability (E. g., Dye, “Pourquoi et comment se fait un texte canonique?,” 94; Shoemaker, Creating the Qurʾan, 50–52. See also De Prémare, “ʿAbd al-Malik,” 197), it would really come as no surprise if John–a hostile writer dealing with a rival religious tradition–was simply misinformed about the precise contents and arrangement of the Qur’an and/or erred in his recounting thereof, or in other words: John’s testimony is highly equivocal evidence (Sinai, “Part I,” 286–87. For more on the debate over John’s reliability and his sources, see Becker, “Christian Polemic,” 244–47/4–7; Merrill, “Of the Tractate of John of Damascus on Islam”; Mey endorff, “Byzantine Views of Islam,” esp. 118; Sahas, John of Damascus, ch. 5; Hoyland, Seeing Islam, 488–89 (incl. n116); Louth, St John Damascene, 79–81; Popov, “Speaking His Mind”; Neil, “The Earliest Greek Understandings of Islam,” 220–22; Schadler, John of Damascus, chs. 3–4).

Secondly, De Prémare et al. posit that al-Ḥajjāj disseminated the canonical qur’anic text-type and ruthlessly purged any and all prior qur’anic texts and traditions c. 700 CE; yet John, who was writing in the 730s CE or later, apparently still had access to pre-canonical (or as De Prémare et al. would have it, pre-Ḥajjājian) qur’anic texts and traditions. This poses an obvious problem for De Prémare et al.: If John was writing three decades or more after the Ḥajjājian canonization, why were the effects thereof not at all evident in John’s writing? (Sinai, "Part I" 287). In other words, even for proponents of the Ḥajjājian hypothesis, there is a reason to suppose that John was really just referring to the canonical (or, as De Prémare et al. would have it, the Ḥajjājian) text-type.

¬U7 (P. Hamb. Arab. 68) is likely a canonical extract with scribal errors, rather than an uncollected text.

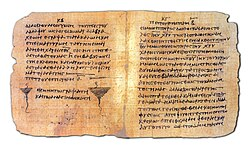

The problem of equivocality also applies to De Prémare et al.’s appeal (¬U6) to the Disputation, which Sinai argues could simply reflect the outsized importance of Sūrat al-Baqarah within the Qur’an, leading the Disputation’s Christian author to wrongly assume that Sūrat al-Baqarah was distinct from the rest of the Qur’an. However, David Taylor offers another explanation: The Disputation distinguishes between Sūrat al-Baqarah and the rest of the Qur’an because it is citing a polemical Christian tradition that identifies a monk named Sergius Baḥīrā as the author of the former and Muḥammad as the author of the latter. In other words, according to the Disputation, Muslims variously derive their doctrines from the Torah, the Gospel, the Qur’an (i. e., from Muḥammad), and Sūrat al-Baqarah (i. e., ultimately from Sergius Baḥīrā). The Disputation is thus referring here to the alleged origins of different parts of the Qur’an in Muḥammad’s time, not describing the state of the text after Muḥammad’s death (let alone after ʿUthmān’s death) (Taylor, “Disputation,” 190–200, esp. 193). This brings us finally to Shoemaker’s appeal (¬U7) to P. Hamb. Arab. 68, which even the recent editors thereof have acknowledged may simply be a vademecum or extract of Sūrat al-Baqarah from the canonical Qur’an (Tillier and Vanthieghem, The Book of the Cow, 37, 39. Likewise, see Déroche, “Forward,” in ibid., xi. Additionally, see Tiller, Vanthieghem, and Colini, “History of a Fragmentary “Sūra of the Cow”.”). This explanation is strengthened by the fact that literally all of the forty-one variants contained in this manuscript are consistent with being scribal errors relative to the canonical text (Tillier and Vanthieghem, The Book of the Cow, 21 ff). This is exactly what would be predicted for the scenario of a canon-derived vade mecum, in contrast to Shoemaker’s hypothesis that the manuscript embodies some kind of pre-canonical–indeed, a free-floating or pre-collected–version of the text. In short, P. Hamb. Arab. 68 is at best equivocal evidence of an uncanonized Qur’an in the late-seventh or early-eighth century CE, and at worst inconsistent with such a hypothesis, most likely being a product of the canonical text-type.

The problem of equivocality also applies to De Prémare et al.’s appeal (¬U6) to the Disputation, which Sinai argues could simply reflect the outsized importance of Sūrat al-Baqarah within the Qur’an, leading the Disputation’s Christian author to wrongly assume that Sūrat al-Baqarah was distinct from the rest of the Qur’an. However, David Taylor offers another explanation: The Disputation distinguishes between Sūrat al-Baqarah and the rest of the Qur’an because it is citing a polemical Christian tradition that identifies a monk named Sergius Baḥīrā as the author of the former and Muḥammad as the author of the latter. In other words, according to the Disputation, Muslims variously derive their doctrines from the Torah, the Gospel, the Qur’an (i. e., from Muḥammad), and Sūrat al-Baqarah (i. e., ultimately from Sergius Baḥīrā). The Disputation is thus referring here to the alleged origins of different parts of the Qur’an in Muḥammad’s time, not describing the state of the text after Muḥammad’s death (let alone after ʿUthmān’s death) (Taylor, “Disputation,” 190–200, esp. 193). This brings us finally to Shoemaker’s appeal (¬U7) to P. Hamb. Arab. 68, which even the recent editors thereof have acknowledged may simply be a vademecum or extract of Sūrat al-Baqarah from the canonical Qur’an (Tillier and Vanthieghem, The Book of the Cow, 37, 39. Likewise, see Déroche, “Forward,” in ibid., xi. Additionally, see Tiller, Vanthieghem, and Colini, “History of a Fragmentary “Sūra of the Cow”.”). This explanation is strengthened by the fact that literally all of the forty-one variants contained in this manuscript are consistent with being scribal errors relative to the canonical text (Tillier and Vanthieghem, The Book of the Cow, 21 ff). This is exactly what would be predicted for the scenario of a canon-derived vade mecum, in contrast to Shoemaker’s hypothesis that the manuscript embodies some kind of pre-canonical–indeed, a free-floating or pre-collected–version of the text. In short, P. Hamb. Arab. 68 is at best equivocal evidence of an uncanonized Qur’an in the late-seventh or early-eighth century CE, and at worst inconsistent with such a hypothesis, most likely being a product of the canonical text-type.

Arguments against al-Ḥajjāj 🧵

- ¬Ḥ1. Abbott has argued that there was already a politico-religious need for a canonical qur’anic text prior to the time of ʿAbd al-Malik and al-Ḥajjāj, i. e., during the reigns of ʿUthmān (r. 24–35/644–656) and Muʿāwiyah (r. 41–60/661 680), which undermines the hypothesis (Ḥ4) that al-Ḥajjāj was the Qur’an’s true canonizer (though not Ḥ3, the hypothesis that he redacted an existing canon) (Abbott, The Rise of the North Arabic Script, 48–49). In a similar vein, in response to the more specific hypothesis (a variant of Ḥ3) that al-Ḥajjāj removed anti-Umayyad passages from the Qur’an, Abū l-Qāsim al-Khūʾī has argued that Muʿāwiyah would have made such an attempt already (Khūʾī, Bayān, 219–20 [= Prolegomena, 151]).

- ¬Ḥ2. Donner and Sinai have both argued that the Qur’an contains no clear references to the first fitnah and all of the conflicts, sects, doctrines, events, ter minology, etc., that arose or occurred therein and thereafter, which is incon sistent with the hypothesis (Ḥ4) that the qur’anic text of the extant canon remained open, fluid, or unfixed after ʿUthmān’s death. In short, there are no post-ʿUthmānic anachronisms in the Qur’an, which is inconsistent with a post-ʿUthmānic canonization. Donner, Narratives, ch. 1; Sinai, “Part II,” 515 ff.; idem, The Qurʾan, 47; idem, “Christian Ele phant,” 75 ff. Indeed, as Sinai emphasizes, the qur’anic text does not even seem to contain con quest-era anachronisms, an observation reiterated in Cook, The Koran, 133. This implies that the Qur’an’s contents had already substantially congealed prior to the ʿUthmānic canonization–an implication that the undertext of the DAM 01–27.1, or Ṣanʿāʾ 1 palimpsest, seems to confirm, as will be discussed more below (s. v. ¬Ḥ14).

- ¬Ḥ3. Schoeler and Sinai have both argued that the presence of various linguistic archaisms, obscurities, and inconsistencies in the canonical qur’anic text is inconsistent with the hypothesis (Ḥ4) of a Ḥajjājian (or any late) canonization, since we would expect successive generations of scribes, tradents, and/ or exegetes (e. g., up until c. 700 CE) to have glossed, updated, or corrected an unfixed text in accordance with their changing linguistic norms and under standings (Schoeler, “Codification,” 788–89; Sinai, “Part II,” 519–20; idem, “Christian Elephant,” 81 ff. See also Cook, The Koran, 133).

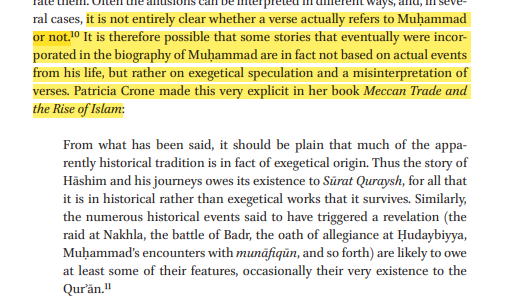

- ¬Ḥ4. Sinai has argued that the highly allusive and uncontextualized character of the canonical qur’anic text is inconsistent with the hypothesis (Ḥ4) of a Ḥajjā jian (or any late) canonization, since we would otherwise expect successive generations of scribes, tradents, and/or exegetes (e. g., up until c. 700 CE) to have incorporated into the as-yet-unfixed qur’anic text biographical details and narrative elaborations from the ancillary corpus of exegetical and Sīrah Maghāzī reports that was already emerging towards the end of the first/seventh century (Sinai, “Part II,” 517–19; idem, “Christian Elephant,” 81 ff.).

- ¬Ḥ5. Muḥammad ʿAbd al-ʿAẓīm al-Zurqānī and al-Khūʾī have both argued (contra Ḥ3–4) that thousands of Qur’an-memorizers (ḥuffāẓ) existed in the time of al-Ḥajjāj, whose memorizations of the Qur’an could not have been overwrit ten by al-Ḥajjāj, even if he had replaced every qur’anic codex (Zurqānī, Manāhil al-ʿirfān, 1:274; Khūʾī, Bayān, 219 [= Prolegomena, 151]).

- ¬Ḥ6. al-Zurqānī has argued (contra Ḥ3–4) that the leading religious figures of al-Ḥajjāj’s time would have resisted and fought against any attempt by him to alter or replace the text of the Qur’an.

- ¬Ḥ7. al-Zurqānī and al-Khūʾī have both argued (contra Ḥ3–4) that al-Ḥajjāj, a mere governor with no authority over the domains of other governors, could not have imposed a new version of the Qur’an across the entire Arab empire.

- ¬Ḥ8. Sadeghi and Sinai have both argued (contra Ḥ3–4) that it is highly unlikely that the Umayyads could have successfully imposed a new scripture–or a new version of an old scripture–upon the increasingly diffuse and heavily divided Muslim communities of the post-fitnah era, especially the Shīʿah, the Ibāḍiyyah, and other such factions opposed to their rule. As such, the canonical qur’anic text-type shared by the Ahl al-Sunnah, the Shīʿah, the Ibāḍiyyah, etc., must be a common pre-sectarian and thus pre-fitnah inheritance (Sadeghi and Bergmann, “Codex,” 366, 414; Sinai, “Part II,” 510, 516. See also Blachère, Introduc tion, 91–92, and Donner, Narratives, intro).

- ¬Ḥ9. al-Zurqānī, al-Khūʾī, Aʿẓamī, Sadeghi, and Hamdan have variously argued e silentio (contra Ḥ3–4) that the absence of Islamic reports of al-Ḥajjāj’s inter polating and replacing the text of the Qur’an is inconsistent with the his torical occurrence thereof, given that such an imposition would have been widely discussed, criticized, and reported by scholars at the time or the com munity in general; and given that al-Ḥajjāj and the Umayyads could not have suppressed all memories thereof across the community (Zurqānī, Manāhil al-ʿirfān, 1:273–74; Khūʾī, Bayān, 219 [= Prolegomena, 151]; Aʿẓamī, The History of the Qurʾānic Text, 103 n73; Sadeghi and Bergmann, “Codex,” 366; Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 799–800).

- ¬Ḥ10. al-Khūʾī, al-Aʿẓamī, Sadeghi, Hamdan, Sinai, and Yasin Dutton have variously argued e silentio (contra Ḥ3–4) that the absence of any explicit mention of an Umayyad canonization or redaction of the Qur’an even in anti-Umayyad sources (i. e., sources that otherwise enumerate Umayyad crimes and out rages) is inconsistent with the historical occurrence of any such Umayyad canonization or redaction (Khūʾī, Bayān, 219 [= Prolegomena, 151]; Aʿẓamī, The History of the Qurʾānic Text, 103 n73; Sade ghi and Bergmann, “Codex,” 366; Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 799–800; Sinai, “Part II,” 510–11; Dutton, “The Form of the Qurʾan,” 188).

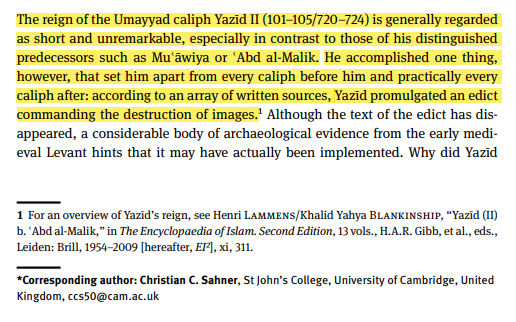

- ¬Ḥ11. Sinai has argued e silentio (contra Ḥ3–4) that the absence of any mention of al-Ḥajjāj’s redaction or canonization of the Qur’an by John of Damascus is inconsistent with the historical occurrence of any such Ḥajjājian redaction or canonization, since it is reasonable to expect that John–a critic of Islam who lived in the Umayyad heartland of Syria during ʿAbd al-Malik’s reign–would have seized upon such an occurrence to delegitimize the Qur’an (Sinai, “Part I,” 287).

- ¬Ḥ12. Sinai and Van Putten have both appealed to the fact that multiple qur’anic manuscripts of the canonical text-type have been radiocarbon dated to before the time of ʿAbd al-Malik and al-Ḥajjāj with a high degree of prob ability, which is strong evidence against the hypothesis (Ḥ4) that al-Ḥajjāj was responsible for producing and establishing this canonical text-type (The Qurʾan, 46, 56 n34, citing Dutton, “An Umayyad Fragment,” esp. 63–64, and Marx and Jocham, “Datierungen” [= “Radiocarbon (14C) Dating”]. Likewise, Van Putten, “The Grace of God,” 275 ff., 279). Moreover, as Van Putten in particular has emphasized, the ultimate archetype behind all of these extant witnesses to the canonical text-type must be earlier still, which further strengthens the hypothesis of a pre-Ḥajjājian canonization (Van Putten, “The Grace of God,” 274, 279).

- ¬Ḥ13. Van Putten has appealed to the paleographical research of Déroche, who identified the “O1” Arabic script-style with the official media of ʿAbd al-Malik and various “Ḥijāzī” script-styles with the preceding era; and, on this basis, dated Codex Parisino-petropolitanus and other such “Ḥijāzī” manuscripts of the canonical text-type to the pre-Marwanid era. It follows from this that the canonical text-type was not produced by al-Ḥajjāj and predates him (contra Ḥ4) (Déroche, Qurʾans of the Umayyads, e. g., 73, 97–99, 139).

- ¬Ḥ14. Sinai has appealed to Sadeghi’s research on the famous DAM 01–27.1 (or Ṣanʿāʾ 1) palimpsest to undermine the specific hypothesis (Ḥ4) that al-Ḥajjāj com posed or collected the Qur’an (Sinai, “Part I,” 275–76; idem, “Part II,” 513–14; idem, The Qurʾan, 46, 56 n35). The parchment of this manuscript has been radiocarbon dated prior to 660 CE with a > 95 % probability and prior to 646 CE with a 75.1 % probability (Sadeghi and Bergmann, “Codex,” 348–54, 383). The manuscript’s so-called “C-1” undertext, which was likely written soon after the parchment was initially produced,185 preserves a non-canonical text-type of the Qur’an: the order of the sūrahs that survive in this fragmentary manuscript differs from the canonical order; the sūrahs in question share the same verses in the same order as their canon ical counterparts; but the verses in question often differ in wording–with omissions, substitutions, assimilations, and mild paraphrases–from their canonical counterparts.186 On various historical and textual-critical grounds, Sadeghi has concluded that the C-1 and canonical text-types are not mutually dependent, but instead co-descend from a written archetype, i. e., an even earlier version of the Qur’an–a version of the Qur’an that existed prior to DAM 01–27.1, which itself likely predates 646 CE–with the same sūrahs con taining approximately the same verses as those shared by DAM 01–27.1 and the extant canon

- ¬Ḥ1. Abbott has argued that there was already a politico-religious need for a canonical qur’anic text prior to the time of ʿAbd al-Malik and al-Ḥajjāj, i. e., during the reigns of ʿUthmān (r. 24–35/644–656) and Muʿāwiyah (r. 41–60/661 680), which undermines the hypothesis (Ḥ4) that al-Ḥajjāj was the Qur’an’s true canonizer (though not Ḥ3, the hypothesis that he redacted an existing canon) (Abbott, The Rise of the North Arabic Script, 48–49). In a similar vein, in response to the more specific hypothesis (a variant of Ḥ3) that al-Ḥajjāj removed anti-Umayyad passages from the Qur’an, Abū l-Qāsim al-Khūʾī has argued that Muʿāwiyah would have made such an attempt already (Khūʾī, Bayān, 219–20 [= Prolegomena, 151]).

- ¬Ḥ2. Donner and Sinai have both argued that the Qur’an contains no clear references to the first fitnah and all of the conflicts, sects, doctrines, events, ter minology, etc., that arose or occurred therein and thereafter, which is incon sistent with the hypothesis (Ḥ4) that the qur’anic text of the extant canon remained open, fluid, or unfixed after ʿUthmān’s death. In short, there are no post-ʿUthmānic anachronisms in the Qur’an, which is inconsistent with a post-ʿUthmānic canonization. Donner, Narratives, ch. 1; Sinai, “Part II,” 515 ff.; idem, The Qurʾan, 47; idem, “Christian Ele phant,” 75 ff. Indeed, as Sinai emphasizes, the qur’anic text does not even seem to contain con quest-era anachronisms, an observation reiterated in Cook, The Koran, 133. This implies that the Qur’an’s contents had already substantially congealed prior to the ʿUthmānic canonization–an implication that the undertext of the DAM 01–27.1, or Ṣanʿāʾ 1 palimpsest, seems to confirm, as will be discussed more below (s. v. ¬Ḥ14).

- ¬Ḥ3. Schoeler and Sinai have both argued that the presence of various linguistic archaisms, obscurities, and inconsistencies in the canonical qur’anic text is inconsistent with the hypothesis (Ḥ4) of a Ḥajjājian (or any late) canonization, since we would expect successive generations of scribes, tradents, and/ or exegetes (e. g., up until c. 700 CE) to have glossed, updated, or corrected an unfixed text in accordance with their changing linguistic norms and under standings (Schoeler, “Codification,” 788–89; Sinai, “Part II,” 519–20; idem, “Christian Elephant,” 81 ff. See also Cook, The Koran, 133).

- ¬Ḥ4. Sinai has argued that the highly allusive and uncontextualized character of the canonical qur’anic text is inconsistent with the hypothesis (Ḥ4) of a Ḥajjā jian (or any late) canonization, since we would otherwise expect successive generations of scribes, tradents, and/or exegetes (e. g., up until c. 700 CE) to have incorporated into the as-yet-unfixed qur’anic text biographical details and narrative elaborations from the ancillary corpus of exegetical and Sīrah Maghāzī reports that was already emerging towards the end of the first/seventh century (Sinai, “Part II,” 517–19; idem, “Christian Elephant,” 81 ff.).

- ¬Ḥ5. Muḥammad ʿAbd al-ʿAẓīm al-Zurqānī and al-Khūʾī have both argued (contra Ḥ3–4) that thousands of Qur’an-memorizers (ḥuffāẓ) existed in the time of al-Ḥajjāj, whose memorizations of the Qur’an could not have been overwrit ten by al-Ḥajjāj, even if he had replaced every qur’anic codex (Zurqānī, Manāhil al-ʿirfān, 1:274; Khūʾī, Bayān, 219 [= Prolegomena, 151]).

- ¬Ḥ6. al-Zurqānī has argued (contra Ḥ3–4) that the leading religious figures of al-Ḥajjāj’s time would have resisted and fought against any attempt by him to alter or replace the text of the Qur’an.

- ¬Ḥ7. al-Zurqānī and al-Khūʾī have both argued (contra Ḥ3–4) that al-Ḥajjāj, a mere governor with no authority over the domains of other governors, could not have imposed a new version of the Qur’an across the entire Arab empire.

- ¬Ḥ8. Sadeghi and Sinai have both argued (contra Ḥ3–4) that it is highly unlikely that the Umayyads could have successfully imposed a new scripture–or a new version of an old scripture–upon the increasingly diffuse and heavily divided Muslim communities of the post-fitnah era, especially the Shīʿah, the Ibāḍiyyah, and other such factions opposed to their rule. As such, the canonical qur’anic text-type shared by the Ahl al-Sunnah, the Shīʿah, the Ibāḍiyyah, etc., must be a common pre-sectarian and thus pre-fitnah inheritance (Sadeghi and Bergmann, “Codex,” 366, 414; Sinai, “Part II,” 510, 516. See also Blachère, Introduc tion, 91–92, and Donner, Narratives, intro).

- ¬Ḥ9. al-Zurqānī, al-Khūʾī, Aʿẓamī, Sadeghi, and Hamdan have variously argued e silentio (contra Ḥ3–4) that the absence of Islamic reports of al-Ḥajjāj’s inter polating and replacing the text of the Qur’an is inconsistent with the his torical occurrence thereof, given that such an imposition would have been widely discussed, criticized, and reported by scholars at the time or the com munity in general; and given that al-Ḥajjāj and the Umayyads could not have suppressed all memories thereof across the community (Zurqānī, Manāhil al-ʿirfān, 1:273–74; Khūʾī, Bayān, 219 [= Prolegomena, 151]; Aʿẓamī, The History of the Qurʾānic Text, 103 n73; Sadeghi and Bergmann, “Codex,” 366; Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 799–800).

- ¬Ḥ10. al-Khūʾī, al-Aʿẓamī, Sadeghi, Hamdan, Sinai, and Yasin Dutton have variously argued e silentio (contra Ḥ3–4) that the absence of any explicit mention of an Umayyad canonization or redaction of the Qur’an even in anti-Umayyad sources (i. e., sources that otherwise enumerate Umayyad crimes and out rages) is inconsistent with the historical occurrence of any such Umayyad canonization or redaction (Khūʾī, Bayān, 219 [= Prolegomena, 151]; Aʿẓamī, The History of the Qurʾānic Text, 103 n73; Sade ghi and Bergmann, “Codex,” 366; Hamdan, “The Second Maṣāḥif Project,” 799–800; Sinai, “Part II,” 510–11; Dutton, “The Form of the Qurʾan,” 188).

- ¬Ḥ11. Sinai has argued e silentio (contra Ḥ3–4) that the absence of any mention of al-Ḥajjāj’s redaction or canonization of the Qur’an by John of Damascus is inconsistent with the historical occurrence of any such Ḥajjājian redaction or canonization, since it is reasonable to expect that John–a critic of Islam who lived in the Umayyad heartland of Syria during ʿAbd al-Malik’s reign–would have seized upon such an occurrence to delegitimize the Qur’an (Sinai, “Part I,” 287).

- ¬Ḥ12. Sinai and Van Putten have both appealed to the fact that multiple qur’anic manuscripts of the canonical text-type have been radiocarbon dated to before the time of ʿAbd al-Malik and al-Ḥajjāj with a high degree of prob ability, which is strong evidence against the hypothesis (Ḥ4) that al-Ḥajjāj was responsible for producing and establishing this canonical text-type (The Qurʾan, 46, 56 n34, citing Dutton, “An Umayyad Fragment,” esp. 63–64, and Marx and Jocham, “Datierungen” [= “Radiocarbon (14C) Dating”]. Likewise, Van Putten, “The Grace of God,” 275 ff., 279). Moreover, as Van Putten in particular has emphasized, the ultimate archetype behind all of these extant witnesses to the canonical text-type must be earlier still, which further strengthens the hypothesis of a pre-Ḥajjājian canonization (Van Putten, “The Grace of God,” 274, 279).

- ¬Ḥ13. Van Putten has appealed to the paleographical research of Déroche, who identified the “O1” Arabic script-style with the official media of ʿAbd al-Malik and various “Ḥijāzī” script-styles with the preceding era; and, on this basis, dated Codex Parisino-petropolitanus and other such “Ḥijāzī” manuscripts of the canonical text-type to the pre-Marwanid era. It follows from this that the canonical text-type was not produced by al-Ḥajjāj and predates him (contra Ḥ4) (Déroche, Qurʾans of the Umayyads, e. g., 73, 97–99, 139).

- ¬Ḥ14. Sinai has appealed to Sadeghi’s research on the famous DAM 01–27.1 (or Ṣanʿāʾ 1) palimpsest to undermine the specific hypothesis (Ḥ4) that al-Ḥajjāj com posed or collected the Qur’an (Sinai, “Part I,” 275–76; idem, “Part II,” 513–14; idem, The Qurʾan, 46, 56 n35). The parchment of this manuscript has been radiocarbon dated prior to 660 CE with a > 95 % probability and prior to 646 CE with a 75.1 % probability (Sadeghi and Bergmann, “Codex,” 348–54, 383). The manuscript’s so-called “C-1” undertext, which was likely written soon after the parchment was initially produced,185 preserves a non-canonical text-type of the Qur’an: the order of the sūrahs that survive in this fragmentary manuscript differs from the canonical order; the sūrahs in question share the same verses in the same order as their canon ical counterparts; but the verses in question often differ in wording–with omissions, substitutions, assimilations, and mild paraphrases–from their canonical counterparts.186 On various historical and textual-critical grounds, Sadeghi has concluded that the C-1 and canonical text-types are not mutually dependent, but instead co-descend from a written archetype, i. e., an even earlier version of the Qur’an–a version of the Qur’an that existed prior to DAM 01–27.1, which itself likely predates 646 CE–with the same sūrahs con taining approximately the same verses as those shared by DAM 01–27.1 and the extant canon

Sinai has variously countered against arguments of Shoemaker. Firstly, the specific conditions of post-Muḥammadan and especially post-ʿUthmānic Muslim society–the conquests, civil wars, sectarian debates, and so on–generate the rea sonable expectation that a text or corpus created or updated after Muḥammad and especially after ʿUthmān would bear an imprint of said conditions (Sinai, “Christian Elephant,” 75 ff.). Secondly, the Qur’an appears to be free not merely of ex eventu prophecies, but of any of the major developments and interests that arose in the time between Muḥammad and al-Ḥajjāj, including sectarian disputes (Sinai, “Part II,” 515–16; idem, “Christian Elephant,” 75 ff). Thirdly, any notion that the composers or redactors of the Qur’an unto and/or under al-Ḥajjāj deliberately refrained from leaving their ideological and temporal fingerprints on the text is highly implausi ble, especially in light of the complete lack of this kind of compunction evident in the early Ḥadīth corpus. Fourthly, those passages in the Qur’an that even Sinai concedes may be post-Muḥammadan still fit into the era between Muḥammad and ʿUthmān. Fifthly, Dye et al.’s putative examples of post-ʿUthmānic compositions in the Qur’an are highly debatable. Sixthly, Shoemaker’s argument that anti-Jew ish and anti-Christian passages postdate Muḥammad and ʿUthmān rests upon the assumption that Donner’s famous hypothesis that Islam began as an ecumenical community of believers is correct–a hypothesis that scholars like Sinai reject in the first place, independently of the canonization debate. Seventhly, Dye and Shoe maker’s contention that the Qur’an was assembled by al-Ḥajjāj from entire texts and compositions that were updated or even created during the great conquests, civil wars, sectarian disputes, Umayyad hegemony, etc., makes it all the more likely, on such a view, that the Qur’an would contain blatant post-Muḥammadan and espe cially post-ʿUthmānic anachronisms (which it does not).

It should also be noted that, even if one accepts Donner’s “believers” thesis, Shoemaker’s appeal to anti-Jewish and anti-Christian anachronisms in the Qur’an remains weak. The hypothesis of an early ecumenical community of believers in no way entails or predicts that the community in question would not conflict with some Jews and Christians, nor that Muḥammad would not express criticisms of some Jews and Christians in his preaching and teaching. In fact, this point has already been addressed by both Donner and Juan Cole, who variously argue that qur’anic criticisms of Jews and Christians tend to be directed against certain Jewish and Christian communities and sects, or specific beliefs and practices, rather than Jews and Christians unconditionally (Donner, “From Believers to Muslims,” esp. 24–28; idem, Muhammad, ch. 2, esp. 70–72, 77; Cole). Indeed, it would be strange if Muḥammad, who was the leader of a monotheistic reform movement on Donner’s view, expressed no criticisms of the preceding monotheistic traditions. Thus, even on Donner’s view, there is no strong reason to think that qur’anic criticisms of Jews and Christians betray a later hand, any more than the qur’anic use of terms like “submitters” or “exclusive devotees” (muslimūn) to describe its followers and the correct attitude that they should adopt towards God (Pace Donner, “Dīn, Islām, und Muslim im Koran,” esp. 132–33. For the meaning of the terms muslim and islām in the Qur’an, see Goudarzi, “Worship,” esp. 41–46).

It should also be noted that, even if one accepts Donner’s “believers” thesis, Shoemaker’s appeal to anti-Jewish and anti-Christian anachronisms in the Qur’an remains weak. The hypothesis of an early ecumenical community of believers in no way entails or predicts that the community in question would not conflict with some Jews and Christians, nor that Muḥammad would not express criticisms of some Jews and Christians in his preaching and teaching. In fact, this point has already been addressed by both Donner and Juan Cole, who variously argue that qur’anic criticisms of Jews and Christians tend to be directed against certain Jewish and Christian communities and sects, or specific beliefs and practices, rather than Jews and Christians unconditionally (Donner, “From Believers to Muslims,” esp. 24–28; idem, Muhammad, ch. 2, esp. 70–72, 77; Cole). Indeed, it would be strange if Muḥammad, who was the leader of a monotheistic reform movement on Donner’s view, expressed no criticisms of the preceding monotheistic traditions. Thus, even on Donner’s view, there is no strong reason to think that qur’anic criticisms of Jews and Christians betray a later hand, any more than the qur’anic use of terms like “submitters” or “exclusive devotees” (muslimūn) to describe its followers and the correct attitude that they should adopt towards God (Pace Donner, “Dīn, Islām, und Muslim im Koran,” esp. 132–33. For the meaning of the terms muslim and islām in the Qur’an, see Goudarzi, “Worship,” esp. 41–46).

Shoemaker has also objected to Sinai’s appeal (¬Ḥ10) to the silence of anti Umayyad sources by asserting that continual Umayyad and later Sunnī threats and violence throughout history compelled the Shīʿah in particular to forget that al-Ḥajjāj had created the Qur’an and forced it upon them. In other words, accord ing to Shoemaker, the particular conditions and pressures of early Islamic history were such that we would not expect Shīʿī memories of the Qur’an’s true Ḥajjājian provenance to have survived unto the extant sources.

There are three problems with Shoemaker’s counterargument. Firstly, it fits awkwardly with the already-mentioned fact that the Shīʿah and other anti-Umayyad factions remembered and recorded numerous other Umayyad crimes and sins: If the Shīʿah and others were able to transmit such material, why not reports of the comparatively greater outrage of al-Ḥajjāj’s creating or redacting scripture? Sec ondly, Shoemaker’s hypothesis is flatly contradicted by other evidence that he himself cites: Shīʿī reports that Abū Bakr, ʿUmar, and ʿUthmān corrupted or cen sored the qur’anic text in some way. The survival of such reports in Shīʿī sources proves that the Shīʿah were willing and able to record reports that contradict the orthodox Sunnī narrative of the Qur’an’s history, which is inconsistent with Shoe maker’s hypothesis that a Shīʿī fear of contradicting said narrative drove them to abandon all memories and reports of al-Ḥajjāj and the Qur’an. Thirdly, as Sadeghi has pointed out, the Umayyads generally come across as an embattled dynasty who did not and could not micromanage Muslim memory and opinion (Sadeghi and Bergmann, “Codex,” 366).

There are three problems with Shoemaker’s counterargument. Firstly, it fits awkwardly with the already-mentioned fact that the Shīʿah and other anti-Umayyad factions remembered and recorded numerous other Umayyad crimes and sins: If the Shīʿah and others were able to transmit such material, why not reports of the comparatively greater outrage of al-Ḥajjāj’s creating or redacting scripture? Sec ondly, Shoemaker’s hypothesis is flatly contradicted by other evidence that he himself cites: Shīʿī reports that Abū Bakr, ʿUmar, and ʿUthmān corrupted or cen sored the qur’anic text in some way. The survival of such reports in Shīʿī sources proves that the Shīʿah were willing and able to record reports that contradict the orthodox Sunnī narrative of the Qur’an’s history, which is inconsistent with Shoe maker’s hypothesis that a Shīʿī fear of contradicting said narrative drove them to abandon all memories and reports of al-Ḥajjāj and the Qur’an. Thirdly, as Sadeghi has pointed out, the Umayyads generally come across as an embattled dynasty who did not and could not micromanage Muslim memory and opinion (Sadeghi and Bergmann, “Codex,” 366).

If you would like to see a whole video by @IslamicOrigins on this, I'll leave the link here:

🔍 If you found this thread insightful, please follow and repost to support more historical research and threads like this.

📷 Join the community: x.com/i/communities/…

📷 Join the discussion & access more resources:

📷discord.gg/R4m6SWJRD8

📷 Substack: jordanjournal.substack.com

📷 Join the community: x.com/i/communities/…

📷 Join the discussion & access more resources:

📷discord.gg/R4m6SWJRD8

📷 Substack: jordanjournal.substack.com

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh